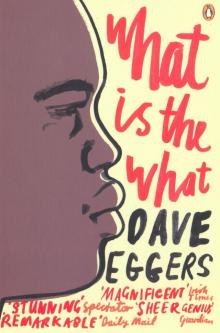

What is the What

Dave Eggers

Title:

What is the What: The Autobiography of Valentino Achak Deng

Author:

Dave Eggers

Year:

2006

Synopsis:

What Is the What: The Autobiography of Valentino Achak Deng is a 2006 novel written by Dave Eggers. It is based on the real life story of Valentino Achak Deng, a Sudanese refugee and member of the Lost Boys of Sudan program.

As a boy, Deng is separated from his family during the Second Sudanese Civil War when the Arab militia, referred to as murahaleen (which is Arabic for traveller), wipes out his Dinka village. He flees on foot with a group of other young boys, (the ‘Lost Boys’), encountering great danger and terrible hardship along the way to a refugee camp in Ethiopia; they are forced to flee a second time to another refugee camp in Kenya and finally, years later, he moves to the United States. The story is told in parallel to subsequent hardships in the United States.

PREFACE

This book is the soulful account of my life: from the time I was separated from my family in Marial Bai to the thirteen years I spent in Ethiopian and Kenyan refugee camps, to my encounters with vibrant Western cultures, in Atlanta and elsewhere.

As you read this book, you will learn about the two and a half million people who have perished in Sudan’s civil war. I was just a boy when the war began. As a helpless human, I survived by trekking across many punishing landscapes while being bombed by Sudanese air forces, while dodging land mines, while being preyed upon by wild beasts and human killers. I fed on unknown fruits, vegetables, leaves, animal carcasses and sometimes went with nothing for days. At certain points, the difficulty was unbearable. I hated myself and attempted to take my own life. Many of my friends, and thousands of my fellow countrymen, did not make it through these struggles alive.

This book was born out of the desire on the part of myself and the author to reach out to others to help them understand the atrocities many successive governments of Sudan committed before and during the civil war. To that end, over the course of many years, I told my story orally to the author. He then concocted this novel, approximating my own voice and using the basic events of my life as the foundation. Because many of the passages are fictional, the result is called a novel. It should not be taken as a definitive history of the civil war in Sudan, nor of the Sudanese people, nor even of my brethren, those known as the Lost Boys. This is simply one man’s story, subjectively told. And though it is fictionalized, it should be noted that the world I have known is not so different from the one depicted within these pages. We live in a time when even the most horrific events in this book could occur, and in most cases did occur.

Even when my hours were darkest, I believed that some day I could share my experiences with readers, so as to prevent the same horrors from repeating themselves. This book is a form of struggle, and it keeps my spirit alive to struggle. To struggle is to strengthen my faith, my hope, and my belief in humanity. Thank you for reading this book, and I wish you a blessed day.

—VALENTINO ACHAK DENG, ATLANTA, 2006

BOOK I

CHAPTER 1

I have no reason not to answer the door so I answer the door. I have no tiny round window to inspect visitors so I open the door and before me is a tall, sturdily built African-American woman, a few years older than me, wearing a red nylon sweatsuit. She speaks to me loudly. ‘You have a phone, sir?’

She looks familiar. I am almost certain that I saw her in the parking lot an hour ago, when I returned from the convenience store. I saw her standing by the stairs, and I smiled at her. I tell her that I do have a phone.

‘My car broke down on the street,’ she says. Behind her, it is nearly night. I have been studying most of the afternoon. ‘Can you let me use your phone to call the police?’ she asks.

I do not know why she wants to call the police for a car in need of repair, but I consent. She steps inside. I begin to close the door but she holds it open. ‘I’ll just be a second,’ she says. It does not make sense to me to leave the door open but I do so because she desires it. This is her country and not yet mine.

‘Where’s the phone?’ she asks.

I tell her my cell phone is in my bedroom. Before I finish the sentence, she has rushed past me and down the hall, a hulk of swishing nylon. The door to my room closes, then clicks. She has locked herself in my bedroom. I start to follow her when I hear a voice behind me.

‘Stay here, Africa.’

I turn and see a man, African-American, wearing a vast powder-blue baseball jacket and jeans. His face is not discernible beneath his baseball hat but he has his hand on something near his waist, as if needing to hold up his pants.

‘Are you with that woman?’ I ask him. I don’t understand anything yet and am angry.

‘Just sit down, Africa,’ he says, nodding to my couch.

I stand. ‘What is she doing in my bedroom?’

‘Just sit your ass down,’ he says, now with venom.

I sit and now he shows me the handle of the gun. He has been holding it all along, and I was supposed to know. But I know nothing; I never know the things I am supposed to know. I do know, now, that I am being robbed, and that I want to be elsewhere.

It is a strange thing, I realize, but what I think at this moment is that I want to be back in Kakuma. In Kakuma there was no rain, the winds blew nine months a year, and eighty thousand war refugees from Sudan and elsewhere lived on one meal a day. But at this moment, when the woman is in my bedroom and the man is guarding me with his gun, I want to be in Kakuma, where I lived in a hut of plastic and sandbags and owned one pair of pants. I am not sure there was evil of this kind in the Kakuma refugee camp, and I want to return. Or even Pinyudo, the Ethiopian camp I lived in before Kakuma; there was nothing there, only one or two meals a day, but it had its small pleasures; I was a boy then and could forget that I was a malnourished refugee a thousand miles from home. In any case, if this is punishment for the hubris of wanting to leave Africa, of harboring dreams of college and solvency in America, I am now chastened and I apologize. I will return with bowed head. Why did I smile at this woman? I smile reflexively and it is a habit I need to break. It invites retribution. I have been humbled so many times since arriving that I am beginning to think someone is trying desperately to send me a message, and that message is ‘Leave this place.’

As soon as I settle on this position of regret and retreat, it is replaced by one of protest. This new posture has me standing up and speaking to the man in the powder-blue coat. ‘I want you two to leave this place,’ I say.

The powder man is instantly enraged. I have upset the balance here, have thrown an obstacle, my voice, in the way of their errand.

‘Are you telling me what do, motherfucker?’

I stare into his small eyes.

‘Tell me that, Africa, are you telling me what to do, motherfucker?’

The woman hears our voices and calls from the bedroom: ‘Will you take care of him?’ She is exasperated with her partner, and he with me.

Powder tilts his head to me and raises his eyebrows. He takes a step toward me and again gestures toward the gun in his belt. He seems about to use it, but suddenly his shoulders slacken, and he drops his head. He stares at his shoes and breathes slowly, collecting himself. When he raises his eyes again, he has regained himself.

‘You’re from Africa, right?’

I nod.

‘All right then. That means we’re brothers.’

I am unwilling to agree.

‘And because we’re brothers and all, I’ll teach you a lesson. Don’t you know you shouldn’t open your door to strangers?’

The question causes me to wince. The simple robbery had been, in a way, acceptable. I have seen rob

beries, have been robbed, on scales much smaller than this. Until I arrived in the United States, my most valuable possession was the mattress I slept on, and so the thefts were far smaller: a disposable camera, a pair of sandals, a ream of white typing paper. All of these were valuable, yes, but now I own a television, a VCR, a microwave, an alarm clock, many other conveniences, all provided by the Peachtree United Methodist Church here in Atlanta. Some of the things were used, most were new, and all had been given anonymously. To look at them, to use them daily, provoked in me a shudder—a strange but genuine physical expression of gratitude. And now I assume all of these gifts will be taken in the next few minutes. I stand before Powder and my memory is searching for the time when I last felt this betrayed, when I last felt in the presence of evil so careless.

With one hand still gripping the handle of the gun, he now puts his hand to my chest. ‘Why don’t you sit your ass down and watch how it’s done?’

I take two steps backward and sit on the couch, also a gift from the church. An apple-faced white woman wearing a tie-dyed shirt brought it the day Achor Achor and I moved in. She apologized that it hadn’t preceded our arrival. The people from the church were often apologizing.

I stare up at Powder and I know who he brings to mind. The soldier, an Ethiopian and a woman, shot two of my companions and almost killed me. She had the same wild light in her eyes, and she first posed as our savior. We were fleeing Ethiopia, chased by hundreds of Ethiopian soldiers shooting at us, the River Gilo full of our blood, and out of the high grasses she appeared. Come to me, children! I am your mother! Come to me! She was only a face in the grey grass, her hands outstretched, and I hesitated. Two of the boys I was running with, boys I had found on the bank of the bloody river, they both went to her. And when they drew close enough, she lifted an automatic rifle and shot through the chests and stomachs of the boys. They fell in front of me and I turned and ran. Come back! she continued. Come to your mother!

I had run that day through the grasses until I found Achor Achor, and with Achor Achor, we found the Quiet Baby, and we saved the Quiet Baby and, for a time, we considered ourselves doctors. This was so many years ago. I was ten years old, perhaps eleven. It’s impossible to know. The man before me, Powder, would never know anything of this kind. He would not be interested. Thinking of that day, when we were driven from Ethiopia back to Sudan, thousands dead in the river, gives me strength against this person in my apartment, and again I stand.

The man now looks at me, like a parent about to do something he regrets that his child has forced him to do. He is so close to me I can smell something chemical about him, a smell like bleach.

‘Are you—Are you—?’ His mouth tightens and he pauses. He takes the gun from his waist and raises it in an upward backhand motion. A blur of black and my teeth crush each other and I watch the ceiling rush over me.

In my life I have been struck in many different ways but never with the barrel of a gun. I have the fortune of having seen more suffering than I have suffered myself, but nevertheless, I have been starved, I have been beaten with sticks, with rods, with brooms and stones and spears. I have ridden five miles on a truckbed loaded with corpses. I have watched too many young boys die in the desert, some as if sitting down to sleep, some after days of madness. I have seen three boys taken by lions, eaten haphazardly. I watched them lifted from their feet, carried off in the animal’s jaws and devoured in the high grass, close enough that I could hear the wet snapping sounds of the tearing of flesh. I have watched a close friend die next to me in an overturned truck, his eyes open to me, his life leaking from a hole I could not see. And yet at this moment, as I am strewn across the couch and my hand is wet with blood, I find myself missing all of Africa. I miss Sudan, I miss the howling grey desert of northwest Kenya. I miss the yellow nothing of Ethiopia.

My view of my assailant is now limited to his waist, his hands. He has stored the gun somewhere and now his hands have my shirt and my neck and he is throwing me from the couch to the carpet. The back of my head hits the end table on the way earthward and two glasses and a clock radio fall with me. Once on the carpet, my cheek resting in its own pooling blood, I know a moment of comfort, thinking that in all likelihood he is finished. Already I am so tired. I feel as if I could close my eyes and be done with this.

‘Now shut the fuck up,’ he says.

These words sound unconvincing, and this gives me solace. He is not an angry man, I realize. He does not intend to kill me; perhaps he has been manipulated by this woman, who is now opening the drawers and closets of my bedroom. She seems to be in control. She is focused on whatever is in my room, and the job of her companion is to neutralize me. It seems simple, and he seems disinclined to inflict further harm upon me. So I rest. I close my eyes and rest.

I am tired of this country. I am thankful for it, yes, I have cherished many aspects of it for the three years I have been here, but I am tired of the promises. I came here, four thousand of us came here, contemplating and expecting quiet. Peace and college and safety. We expected a land without war and, I suppose, a land without misery. We were giddy and impatient. We wanted it all immediately—homes, families, college, the ability to send money home, advanced degrees, and finally some influence. But for most of us, the slowness of our transition—after five years I still do not have the necessary credits to apply to a four-year college—has wrought chaos. We waited ten years at Kakuma and I suppose we did not want to start over here. We wanted the next step, and quickly. But this has not happened, not in most cases, and in the interim, we have found ways to spend the time. I have held too many menial jobs, and currently work at the front desk of a health club, on the earliest possible shift, checking in members and explaining the club’s benefits to prospective members. This is not glamorous, but it represents a level of stability unknown to some. Too many have fallen, too many feel they have failed. The pressures upon us, the promises we cannot keep with ourselves—these things are making monsters of too many of us. And the one person who I felt could help me transcend the disappointment and mundanity of it, an exemplary Sudanese woman named Tabitha Duany Aker, is gone.

Now they are in the kitchen. Now in Achor Achor’s room. Lying here, I begin to calculate what they can take from me. I realize with some satisfaction that my computer is in my car, and will be spared. But Achor Achor’s new laptop will be stolen. It will be my fault. Achor Achor is one of the leaders of the young refugees here in Atlanta and I fear all he needs will be gone when his computer is gone. The records of all the meetings, the finances, thousands of emails. I cannot allow so much to be stolen. Achor Achor has been with me since Ethiopia and I bring him nothing but bad luck.

In Ethiopia I stared into the eyes of a lion. I was perhaps ten years old, sent to the forest to retrieve wood, and the animal stepped slowly from behind a tree. I stood for a moment, such a long time, enough for me to memorize its dead-eyed face, before running. He roared after me but did not chase; I like to believe that he found me too formidable a foe. So I have faced this lion, have faced the guns, a dozen times, of armed Arab militiamen on horseback, their white robes gleaming in the sun. And thus I can do this, can stop this petty theft. Once again I raise myself to my knees.

‘Get the fuck down, motherfucker!’

And my face meets the floor once more. Now the kicking begins. He kicks me in the stomach, and now the shoulder. It hurts most when my bones strike my bones.

‘Fucking Nigerian motherfucker!’

Now he seems to be enjoying himself, and this causes me worry. When there is pleasure, there is often abandon, and mistakes are made. Seven kicks to the ribs, one to the hip, and he rests. I take a breath and assess my damage. It is not great. I curl myself around the corner of the couch and now am determined to stay still. I have never been a fighter, I finally admit to myself. I have survived many oppressions, but have never fought with a man standing in front of me.

‘Fucking Nigerian! So stupid!’

He is heaving, h

is hands on his bent knees.

‘No wonder you motherfuckers are in the Stone Age!’

He gives me one more kick, lighter than the others, but this one directly into my temple, and a burst of white light fills my left eye.

In America I have been called Nigerian before—it must be the most familiar of African countries—but I have never been kicked. Again, though, I have seen it happen. I suppose there is little in the way of violence that I have not seen in Sudan, in Kenya. I spent years in a refugee camp in Ethiopia, and there I watched two young boys, perhaps twelve years old, fighting so viciously over rations that one kicked the other to death. He had not intended to kill his foe, of course, but we were young and very weak. You cannot fight when you have not eaten properly for weeks. The dead boy’s body was unprepared for any trauma, his skin taut over his brittle ribs that were no longer up to the task of encasing his heart. He was dead before he touched the ground. It was just before lunch, and after the boy was carried off, to be buried in the gravelly soil, we were served stewed beans and corn.

Now I plan to say nothing, to simply wait for Powder and his friend to leave. They cannot stay long; surely soon they will have taken all that they want. I can see the pile they are making on our kitchen table, the things they plan to leave with. The TV is there, Achor Achor’s laptop, the VCR, the cordless phones, my cell phone, the microwave.

The sky is darkening, my guests have been in our apartment for twenty minutes or so, and Achor Achor won’t be back for many hours, if at all. His job is similar to the one I once had—at a furniture showroom, in the back room, arranging for the shipping of samples to interior decorators. Even when not at work, he’s seldom home. After many years without female companionship, Achor Achor has found a girlfriend, an African-American woman named Michelle. She is lovely. They met at the community college, in a class, quilting, which Achor Achor registered for by accident. He walked in, was seated next to Michelle, and he never left. She smells of citrus perfume, a flowery citrus, and I see Achor Achor less and less. There was a time when I harbored thoughts of Tabitha this way. I imagined us planning a wedding and creating a brood of children who would speak English as Americans do, but Tabitha lived in Seattle and those plans were still far away. Perhaps I am romanticizing it now. This happened at Kakuma, too; I lost someone very close to me and afterward I believed I could have saved him had I been a better friend to him. But everyone disappears, no matter who loves them.