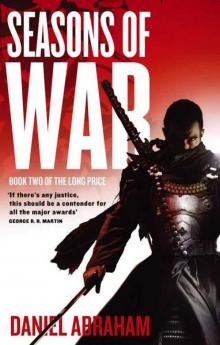

Seasons of War

Daniel Abraham

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

BOOK THREE: AN AUTUMN WAR

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

BOOK FOUR: THE PRICE OF SPRING

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

EPILOGUE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

SEASONS OF WAR

PRAISE FOR DANIELABRAHAM

‘Daniel Abraham is one of the reasons the fantasy genre continues to haunt my dreams. Abraham is fiercely talented, disturbingly human, breathtakingly original and even on his bad days kicks all sorts of literary ass. Welcome to the world of the andats, of the haunted extraordinary poets, a world where men enslave ideas, where these slaves scheme to avenge themselves, where every bad deed spawns more, a world where after the treachery, the conspiracies, the journeys, all that’s ever left in the end are the consequences. Welcome to Daniel Abraham. If you are meeting him for the first time I envy you: you are in for a remarkable journey.’

Junot Diaz, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

‘Daniel Abraham gets better with every book. A Shadow in Summer was among the strongest first novels of the last decade, and A Betrayal in Winter was a terrific second book, but in An Autumn War, Abraham puts both of them in the shade. This book really blows the top off, taking the world of the andat and the poets in new and unexpected directions. An Autumn War will keep you turning pages and break your heart in the bargain. If there’s any justice, this should be a contender for all the major awards.’

George R. R. Martin

‘There is much to love in the Long Price Quartet. It is epic in scope, but character-centred. The setting is unique yet utterly believable. The storytelling is smooth, careful and - best of all - unpredictable. The first two books impressed me, but An Autumn War surpassed them, leaving me stunned and wondering where Abraham will take me in the fourth book.’

Patrick Rothfuss

‘I already knew Daniel Abraham was an excellent writer. An Autumn War is his best novel yet: his quiet compassion for humanity slams hard against his clear-eyed depiction of the ruthless progress of war and the bitter choices people must often make to protect their own. Highly recommended.’

Kate Elliott

‘Abraham’s series gets more mind-expanding with every book. An Autumn War ratchets up the tension and then delivers a stunning ending that will leave you gasping for breath, wondering what bowling ball jut slammed you in the skull.

Yes, it is that good.’

Walter Jon Williams

BY DANIEL ABRAHAM

The Long Price

Shadow and Betrayal

Seasons of War

Seasons of War

DANIEL ABRAHAM

Hachette Digital

www.littlebrown.co.uk

Published by Hachette Digital 2010

Copyright © 2008 by Daniel Abraham

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN : 978 0 7481 2077 2

This ebook produced by JOUVE, FRANCE

Hachette Digital

An imprint of

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DY

An Hachette Livre UK Company

To Scarlet

Acknowledgements

Once again, I would like to extend my thanks to Walter Jon Williams, Melinda Snodgrass, Emily Mah, S. M. Stirling, Terry England, Ian Tregillis, Ty Franck, George R. R. Martin and the other members of the New Mexico Critical Mass Workshop.

I also owe debts of gratitude to Shawna McCarthy and Danny Baror for their enthusiasm and faith in the project, Jim Frenkel for excellent advice, and to my family for supporting me through this very long project.

The World

The Cities of the Khaiem

BOOK THREE: AN AUTUMN WAR

PROLOGUE

Three men came out of the desert. Twenty had gone in.

The setting sun pushed their shadows out behind them, lit their faces a ruddy gold, blinded them. The weariness and pain in their bodies robbed them of speech. On the horizon, something glimmered that was no star, and they moved silently toward it. The farthest tower of Far Galt, the edge of the Empire, beckoned them home from the wastes, and without speaking, each man knew that they would not stop until they stood behind its gates.

The smallest of them shifted the satchel on his back. His gray commander’s tunic hung from his flesh as if the cloth itself were exhausted. His mind turned inward, half-dreaming, and the leather straps of the satchel rubbed against his raw shoulder. The burden had killed seventeen of his men, and now it was his to carry as far as the tower that rose up slowly in the violet air of evening. He could not bring himself to think past that.

One of the others stumbled and fell to his knees on wind-paved stones. The commander paused. He would not lose another, not so near the end. And yet he feared bending down, lifting the man up. If he paused, he might never move again. Grunting, the other man recovered his feet. The commander nodded once and turned again to the west. A breeze stirred the low, brownish grasses, hissing and hushing. The punishing sun made its exit and left behind twilight and the wide swath of stars hanging overhead, cold candles beyond numbering. The night would bring chill as deadly as the midday heat.

It seemed to the commander that the tower did not so much come closer as grow, plantlike. He endured his weariness and pain, and the structure that had been no larger than his thumb was now the size of his hand. The beacon that had seemed steady flickered now, and tongues of flame leapt and vanished. Slowly, the details of the ston

ework came clear; the huge carved relief of the Great Tree of Galt. He smiled, the skin of his lip splitting, wetting his mouth with blood.

‘We’re not going to die,’ one of the others said. He sounded amazed. The commander didn’t respond, and some measureless time later, another voice called for them to stop, to offer their names and the reason that they’d come to this twice-forsaken ass end of the world.

When the commander spoke, his voice was rough, rusting with disuse.

‘Go to your High Watchman,’ he said. ‘Tell him that Balasar Gice has returned.’

Balasar Gice had been in his eleventh year when he first heard the word andat. The river that passed through his father’s estates had turned green one day, and then red. And then it rose fifteen feet. Balasar had watched in horror as the fields vanished, the cottages, the streets and yards he knew. The whole world, it seemed, had become a sea of foul water with only the tops of trees and the corpses of pigs and cattle and men to the horizon.

His father had moved the family and as many of his best men as would fit to the upper stories of the house. Balasar had begged to take the horse his father had given him up as well. When the gravity of the situation had been explained, he changed his pleas to include the son of the village notary, who had been Balasar’s closest friend. He had been refused in that as well. His horses and his playmates were going to drown. His father’s concern was for Balasar, for the family; the wider world would have to look after itself.

Even now, decades later, the memory of those six days was fresh as a wound. The bloated bodies of pigs and cattle and people like pale logs floating past the house. The rich, low scent of fouled water. The struggle to sleep when the rushing at the bottom of the stairs seemed like the whisper of something vast and terrible for which he had no name. He could still hear men’s voices questioning whether the food would last, whether the water was safe to drink, and whether the flood was natural, a catastrophe of distant rains, or an attack by the Khaiem and their andat.

He had not known then what the word meant, but the syllables had taken on the stench of the dead bodies, the devastation where the village had been, the emptiness and the destruction. It was only much later - after the water had receded, the dead had been mourned, the village rebuilt - that he learned how correct he had been.

Nine generations of fathers had greeted their new children into the world since the God Kings of the East had turned upon each other, his history tutor told him. When the glory that had been the center of all creation fell, its throes had changed the nature of space. The lands that had been great gardens and fields were deserts now, permanently altered by the war. Even as far as Galt and Eddensea, the histories told of weeks of darkness, of failed crops and famine, a sky dancing with flames of green, a sound as if the earth were tearing itself apart. Some people said the stars themselves had changed positions.

But the disasters of the past grew in the telling or faded from memory. No one knew exactly how things had been those many years ago. Perhaps the Emperor had gone mad and loosed his personal god-ghost - what they called andat - against his own people, or against himself. Or there might have been a woman, the wife of a great lord, who had been taken by the Emperor against her will. Or perhaps she’d willed it. Or the thousand factions and minor insults and treacheries that accrue around power had simply followed their usual course.

As a boy, Balasar had listened to the story, drinking in the tales of mystery and glory and dread. And, when his tutor had told him, somber of tone and gray, that there were only two legacies left by the fall of the God Kings - the wastelands that bordered Far Galt and Obar State, and the cities of the Khaiem where men still held the andat like Cooling, Seedless, Stone-Made-Soft - Balasar had understood the implication as clearly as if it had been spoken.

What had happened before could happen again at any time and without warning.

‘And that’s what brought you?’ the High Watchman said. ‘It’s a long walk from a little boy at his lessons to this place.’

Balasar smiled again and leaned forward to sip bitter kafe from a rough tin mug. His room was baked brick and close as a cell. A cruel wind hissed outside the thick walls, as it had for the three long, feverish days since he had returned to the world. The small windows had been scrubbed milky by sandstorms. His little wounds were scabbing over, none of them reddened or hot to the touch, though the stripe on his shoulder where the satchel strap had been would doubtless leave a scar.

‘It wasn’t as romantic as I’d imagined,’ he said. The High Watchman laughed, and then, remembering the dead, sobered. Balasar shifted the subject. ‘How long have you been here? And who did you offend to get yourself sent to this . . . lovely place?’

‘Eight years. I’ve been eight years at this post. I didn’t much care for the way things got run in Acton. I suppose this was my way of saying so.’

‘I’m sure Acton felt the loss.’

‘I’m sure it didn’t. But then, I didn’t do it for them.’

Balasar chuckled.

‘That sounds like wisdom,’ Balasar said, ‘but eight years here seems an odd place for wisdom to lead you.’

The High Watchman smacked his lips and shrugged.

‘It wasn’t me going inland,’ he said. Then, a moment later, ‘They say there’s still andat out there. Haunting the places they used to control.’

‘There aren’t,’ Balasar said. ‘There are other things. Things they made or unmade. There’s places where the air goes bad on you - one breath’s fine, and the next it’s like something’s crawling into you. There’s places where the ground’s thin as eggshell and a thousand-foot drop under it. And there are living things too - things they made with the andat, or what happened when the things they made bred. But the ghosts don’t stay once their handlers are gone. That isn’t what they are.’

Balasar took an olive from his plate, sucked away the flesh, and spat back the stone. For a moment, he could hear voices in the wind. The words of men who’d trusted and followed him, even knowing where he would take them. The voices of the dead whose lives he had spent. Coal and Eustin had survived. The others - Little Ott, Bes, Mayarsin, Laran, Kellem, and a dozen more - were bones and memory now. Because of him. He shook his head, clearing it, and the wind was only wind again.

‘No offense, General,’ the High Watchman said, ‘but there’s not enough gold in the world for me to try what you did.’

‘It was necessary,’ Balasar said, and his tone ended the conversation.

The journey to the coast was easier than it should have been. Three men, traveling light. The others were an absence measured in the ten days it took to reach Lawton. It had taken sixteen coming from. The arid, empty lands of the East gave way to softly rolling hills. The tough yellow grasses yielded to blue-green almost the color of a cold sea, wavelets dancing on its surface. Farmsteads appeared off the road, windmills with broad blades shifting in the breezes; men and women and children shared the path that led toward the sea. Balasar forced himself to be civil, even gracious. If the world moved the way he hoped, he would never come to this place again, but the world had a habit of surprising him.

When he’d come back from the campaign in the Westlands, he’d thought his career was coming to its victorious end. He might take a place in the Council or at one of the military colleges. He even dared to dream of a quiet estate someplace away from the yellow coal smoke of the great cities. When the news had come - a historian and engineer in Far Galt had divined a map that might lead to the old libraries - he’d known that rest had been a chimera, a thing for other men but never himself. He’d taken the best of his men, the strongest, smartest, most loyal, and come here. He had lost them here. The ones who had died, and perhaps also the ones who had lived.

Coal and Eustin were both quiet as they traveled, both respectful when they stopped to camp for the night. Without conversation, they had all agreed that the cold night air and hard ground was better than the company of men at an inn or wayhouse. Once i

n a while, one or the other would attempt to talk or joke or sing, but it always failed. There was a distance in their eyes, a stunned expression that Balasar recognized from boys stumbling over the wreckage of their first battlefield. They were seasoned fighters, Coal and Eustin. He had seen both of them kill men and boys, knew each of them had raped women in the towns they’d sacked, and still, they had left some scrap of innocence in the desert and were moving away from it with every step. Balasar could not say what that loss would do to them, nor would he insult their manhood by bringing it up. He knew, and that alone would have to suffice. They reached the ports of Parrinshall on the first day of autumn.

Half a hundred ships awaited them: great merchant ships built to haul cargo across the vast emptiness of the southern seas, shallow fishing boats that darted out of port and back again, the ornate three-sailed roundboats of Bakta, the antiquated and changeless ships of the east islands. It was nothing to the ports at Kirinton or Lanniston or Saraykeht, but it was enough. Three berths on any of half a dozen of these ships would take them off Far Galt and start them toward home.