Poor Relations

Compton MacKenzie

Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online DistributedProofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book wasproduced from scanned images available at the InterentArchive.)

POOR RELATIONS

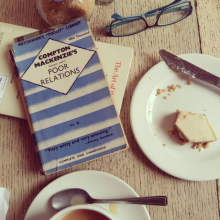

image of the book's cover]

_BY THE SAME AUTHOR_

POOR RELATIONS

SYLVIA & MICHAEL

PLASHERS MEAD

SYLVIA SCARLETT

Harper & Brothers _Publishers_

POOR RELATIONS

By COMPTON MACKENZIE

Author of "SYLVIA SCARLETT" "SYLVIA AND MICHAEL"ETC.

colophon]

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS NEW YORK AND LONDON

POOR RELATIONS

Copyright, 1919, by Harper & Brothers

Printed in the United States of America

Published February, 1920

B-U

THIS THEME IN C MAJOR WITH VARIATIONS IS INSCRIBED TO THE ROMANTIC ANDMYSTERIOUS MAJOR C BY ONE WHO WAS PRIVILEGED TO SERVE UNDER HIM DURINGMORE THAN TWO YEARS OF WAR

CAPRI, APRIL 30, 1919.

POOR RELATIONS

_Poor Relations_

CHAPTER I

There was nothing to distinguish the departure of the _Murmania_ fromthat of any other big liner leaving New York in October for Liverpool orSouthampton. At the crowded gangways there was the usual rain ofultimate kisses, from the quayside the usual gale of speedinghandkerchiefs. Ladies in blanket-coats handed over to the arrangement oftheir table-stewards the expensive bouquets presented by friends who, asthe case might be, had been glad or sorry to see them go. Middle-agedgentlemen, who were probably not at all conspicuous on shore, at oncemade their appearance in caps that they might have felt shy aboutwearing even during their university prime. Children in the firstconfusion of settling down ate more chocolates from the gift boxes lyingabout the cabins than they were likely to be given (or perhaps to want)for some time. Two young women with fresh complexions, short skirts, tamo' shanters, brightly colored jumpers, and big bows to their shoes werealready on familiar terms with one of the junior ship's officers, andtheir laughter (which would soon become one of those unending oceanicaccompaniments that make land so pleasant again) was already competingwith the noise of the crew. Everybody boasted aloud that they fed youreally well on the _Murmania_, and hoped silently that perhaps the senseof being imprisoned in a decaying hot-water bottle (or whatever more orless apt comparison was invented to suggest atmosphere below decks)would pass away in the fresh Atlantic breezes. Indeed it might be said,except in the case of a few ivory-faced ladies already lying back withthe professional aloofness of those who are a prey to chronic headaches,that outwardly optimism was rampant.

It was not surprising, therefore, that John Touchwood, the successfulromantic playwright and unsuccessful realistic novelist, should onfinding himself hemmed in by such invincible cheerfulness surrender tohis own pleasant fancies of home. This was one of those moments when hewas able to feel that the accusation of sentimentality so persistentlylaid against his work by superior critics was rebutted out of the verymouth of real life. He looked round at his fellow passengers as thoughhe would congratulate them on conforming to his later and moreprofitable theory of art; and if occasionally he could not help seeing astewardess with a glance of discreet sympathy reveal to an inquirer theship's provision for human weakness, he did not on this account feelbetter disposed toward morbid intrusions either upon art or life, partlybecause he was himself an excellent sailor and partly because after allas a realist he had unquestionably not been a success.

"Time for a shave before lunch, steward?" he inquired heartily.

"The first bugle will go in about twenty minutes, sir."

John paused for an instant at his own cabin to extract from his suitcasethe particular outrage upon conventional headgear (it was a deerstalkerof Lovat tweed) that he had evolved for this voyage; and presently hewas sitting in the barber shop, wondering at first why anybody should beexpected to buy any of the miscellaneous articles exposed for sale atsuch enhanced prices on every hook and in every nook of the littlesaloon, and soon afterward seriously considering the advantage of a pairof rope-soled shoes upon a heeling deck.

"Very natty things those, sir," said the barber. "I laid in a stock onceat Gib., when we did the southern rowt. Shave you close, sir?"

"Once over, please."

"Skin tender?"

"Rather tender."

"Yes, sir. And the beard's a bit strong, sir. Shave yourself, sir?"

"Usually, but I was up rather early this morning."

"Safety razor, sir?"

"If you think such a description justifiable--yes--a safety."

"They're all the go now, and no mistake ... safety bicycles, safetymatches, safety razors ... they've all come in our time ... yes, sir,just a little bit to the right--thank you, sir! Not your first crossing,I take it?"

"No, my third."

"Interesting place, America. But I am from Wandsworth myself. Hair'sgetting rather thin round the temples. Would you like something tobrisken up the growth a bit? Another time? Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.Parting on the left's it, I think?"

"No grease," said John as fiercely as he ever spoke. The barber seemedto replace the pot of brilliantine with regret.

"What would you like then?" He might have been addressing a spoiltchild. "Flowers-and-honey? Eau-de-quinine? Or perhaps a friction? I'vegot lavingder, carnation, wallflower, vilit, lilerk...."

"Bay rum," John declared, firmly.

The barber sighed for such an unadventurous soul; and John, who couldnot bear to hurt even the most superficial emotions of a barber, changedhis mind and threw him into a smiling bustle of gratification.

"Rather strong," John said, half apologetically; for while the frictionwas being administered the barber had explained in jerks how every timehe went ashore in New York or Liverpool he was in the habit of searchingabout for some novel wash or tonic or pomade, and John did not want tomake him feel that his enterprise was unappreciated.

"Strong is it? Well, that's a good fault, sir."

"Yes, I suppose it is."

"What took my fancy was the natural way it smelled."

"Yes, indeed, painfully natural," John agreed.

He stood up and confronted himself in the barber's mirror; regarding thefair, almost florid man, rather under six feet in height, with sanguineblue eyes and full, but clearly cut, lips therein reflected, he came tothe comforting conclusion that he did not look his forty-two years andnine months; indeed, while his muffled whistle was shaping rather thanuttering the tune of _Nancy Lee_, he nearly asked the barber to guesshis age. However, he decided not to risk it, pulled down the lapels ofhis smoke-colored tweed coat, put on his deerstalker, tipped the barbersufficiently well to secure a parting caress from the brush, promised tomeditate the purchase of the rope-soled shoes, and stepped jauntily inthe direction of the luncheon bugle. If John Touchwood had not been asuccessful romantic playwright and an unsuccessful realistic novelist,he might have found in the spectacle of the first lunch of an Atlanticvoyage an illustration of human madness and the destructive will of thegods. As it was, his capacity for rapidly covering the domestic officesof the brain with the crimson-ramblers of a lush idealism made himforget the base fabric so prettily if obviously concealed. As it was, hefound an exhilaration in all this berserker greed, in the cries ofinquisitive children, in the rumpled appearance of women whom the buglehad torn from their unpacking with the urgency of the last trump, in theacrid smell of pickles, and in the persuasive gesture with which theglistening stewards handed the potatoes while they glared angrily at oneanother over their shoulders. If a cynical realist had in respect ofthis lunch observed to John that a sow's ear was poor material for asilk purse, he would have contested the universal t

ruth of the proverb,for at this moment he was engaged in chinking the small change ofsentimentality in just such a purse.

"How jolly everybody is," he thought, swinging round to his neighbor, agaunt woman in a kind of draggled mantilla, with an effusion ofgood-will that expressed itself in a request to pass her the pickledwalnuts. John fancied an impulse to move away her chair when shedeclined his offer; but of course the chair was fixed, and the only signof her distaste for pickles or conversation was a faint quiver, which toany one less rosy than John might have suggested abhorrence, but whichstruck him as merely shyness. It was now that for the first time hebecame aware of a sickly fragrance that was permeating the atmosphere, afragrance that other people, too, seemed to be noticing by the way inwhich they were looking suspiciously at the stewards.

"Rather oppressive, some of these flowers," said John to the gaunt lady.

"I don't see any flowers at our end of the table," she replied.

And then with an emotion that was very nearly horror John realized that,though the barber was responsible, he must pay the penalty in avicarious mortification. His first impulse was to snatch a napkin andwipe his hair; then he decided to leave the table immediately, becauseafter all nobody _could_ suspect him, in these as yet unvexed waters, ofanything but repletion; finally, hoping that the much powdered ladyopposite swathed in mauve chiffons was getting the discredit for thefragrance, he stayed where he was. Nevertheless, the exhilaration haddeparted; his neighbors all seemed dull folk; and congratulating himselfthat after this first confused lunch he might reasonably expect to beput at the captain's table in recognition of the celebrity that he couldfairly claim, John took from his pocket a bundle of letters which hadarrived just before he had left his hotel and busied himself with themfor the rest of the meal.

His success as a romantic playwright and his failure--or, as he wouldhave preferred to think of it in the satisfaction of fixing the guiltyfragrance upon the lady in mauve chiffons, his comparative failure--as arealistic novelist had not destroyed John's passion for what he called"being practical in small matters," and it was in pursuit of this thathaving arranged his letters in two heaps which he mentally labeled as"business" and "pleasure" he began with the former, as a child begins(or ought to begin) his tea with the bread and butter and ends it withthe plumcake. In John's case, fresh from what really might be describedas a triumphant production in New York, the butter was spread so thicklythat "business" was too forbidding a name for such pleasantly nutritiouscommunications. His agent had sent him the returns of the second week;and playing to capacity in one of the largest New York theaters isnearer to a material paradise than anything outside the Mohammedanreligion. Then there was an offer from one of the chief film companiesto produce his romantic drama of two years ago, that wonderful riot ofcolor and Biblical phraseology, _The Fall of Babylon_. They ventured tothink that the cinematographer would do his imagination more justicethan the theater, particularly as upon their dramatic ranch inCalifornia they now had more than a hundred real camels and eight realelephants. John chuckled at the idea of a few animals compensating forthe absence of his words, but nevertheless ... the entrance ofNebuchadnezzar, yes, it should be wonderfully effective ... and thegreat grass-eating scene, yes, that might positively be more impressiveon the films ... with one or two audiences it had trembled for a momentbetween the sublime and the ridiculous. It was a pity that the offer hadnot arrived before he was leaving New York, but no doubt he should beable to talk it over with the London representatives of the firm. Hullohere was Janet Bond writing to him ... charming woman, charmingactress.... He wandered for a few minutes rather vaguely in the maze ofher immense handwriting, but disentangled his comprehension at last anddeciphered:

THE PARTHENON THEATRE.

Sole Proprietress: Miss Janet Bond.

_October 10, 1910._

DEAR MR. TOUCHWOOD,--I wonder if you have forgotten our talk at SirHerbert's that night? I'm so hoping not. And your scheme for a realJoan of Arc? Do think of me this winter. Your picture of the scene withGilles de Rais--you see I followed your advice and read him up--has_haunted_ me ever since. I can hear the horses' hoofs coming nearer andnearer and the cries of the murdered children. I'm so glad you've had asuccess with _Lucrezia_ in New York. I don't _think_ it would suit mefrom what I read about it. You know how _particular_ my public is.That's why I'm so anxious to play the Maid. When will _Lucrezia_ beproduced in London, and where? There are many rumours. Do come and seeme when you get back to England, and I'll tell you who I've thought ofto play Gilles. I _think_ you'll find him very intelligent. But ofcourse everything depends on your inclination, or should I sayinspiration? And then that wonderful speech to the Bishop! How does itbegin? "Bishop, thou hast betrayed thy holy trust." Do be a littleflattered that I've remembered that line. It needn't _all_ be in blankverse, and I think little Truscott would be so good as the Bishop. Yousee how _enthusiastic_ I am and how I _believe_ in the idea. All goodwishes.

Yours sincerely and hopefully,

JANET BOND.

John certainly was a little flattered that Miss Bond should haveremembered the Maid's great speech to the Bishop of Beauvais, and theactress's enthusiasm roused in him an answering flame, so that the cruetbefore him began to look like the castelated walls of Orleans, and whilehis gaze was fixed upon the bowl of salad he began to compose _Act II.__Scene I_--_Open country. Enter Joan on horseback. From the summit of agrassy knoll she searches the horizon._ So fixedly was John regardinghis heroine on top of the salad that the head steward came over andasked anxiously if there was anything the matter with it. And even whenJohn assured him that there was nothing he took it away and told one ofthe under-stewards to remove the caterpillar and bring a fresh bowl.Meanwhile, John had picked up the other bundle of letters and begun toread his news from home.

65 HILL ROAD,

St. John's Wood, N.W.,

_October 10_.

DEAR JOHN,--We have just read in the _Telegraph_ of your great successand we are both very glad. Edith writes me that she did have a letterfrom you. I dare say you thought she would send it on to us but shedidn't, and of course I understand you're busy only I should have likedto have had a letter ourselves. James asks me to tell you that he isprobably going to do a book on the Cymbalist movement in literature. Hesays that the time has come to take a final survey of it. He is alsowriting some articles for the _Fortnightly Review_. We shall all be soglad to welcome you home again.

Your affectionate sister-in-law,

BEATRICE TOUCHWOOD.

"Poor Beatrice," thought John, penitently. "I ought to have sent her aline. She's a good soul. And James ... what a plucky fellow he is!Always full of schemes for books and articles. Wonderful really, to goon writing for an audience of about twenty people. And I used to grumblebecause my novels hadn't world-wide circulations. Poor old James ... agood fellow."

He picked up the next letter; which he found was from his othersister-in-law.

HALMA HOUSE,

198 Earl's Court Square, S.W.,

_October 9_.

DEAR JOHN,--Well, you've had a hit with _Lucrezia_, lucky man! If yousent out an Australian company, don't you think I might play lead? Iquite understand that you couldn't manage it for me either in London orAmerica, but after all you _are_ the author and you surely have _some_say in the cast. I've got an understudy at the Parthenon, but I can'tstand Janet. Such a selfish actress. She literally doesn't think of anyone but herself. There's a chance I may get a decent part on tour withLambton this autumn. George isn't very well, and it's been rathermiserable this wet summer in the boarding house as Bertram and Violawere ill and kept away from school. I would have suggested their goingdown to Ambles, but Hilda was so very unpleasant when I just hinted atthe idea that I preferred to keep them with me in town. Both childrenask every day when you're coming home. You're quite the favourite uncle.George was delighted with your success. Poor old boy, he's had anotherfinancial disappointment, and your success was quite a consolation.

ELEANOR.

"I wish Eleanor was anywhere but on the stage," John sighed. "But she'sa plucky woman. I _must_ write her a part in my next play. Now forHilda."

He opened his sister's letter with the most genial anticipation, becauseit was written from his new country house in Hampshire, that countyhouse which he had coveted for so long and to which the now faintlyincreasing motion of the _Murmania_ reminded him that he was fastreturning.

AMBLES,

Wrottesford, Hants,

_October 11_.

MY DEAR JOHN,--Just a line to congratulate you on your new success. Lotsof money in it, I suppose. Dear Harold is quite well and happy atAmbles. Quite the young squire! I had a little coolness withEleanor--entirely on her side of course, but Bertram is really such a_bad_ influence for Harold and so I told her that I did not think youwould like her to take possession of your new house before you'd hadtime to live in it yourself. Besides, so many children all at once wouldhave disturbed poor Mama. Edith drove over with Frida the other day andtells me you wrote to her. I should have liked a letter, too, but youalways spoil poor Edith. Poor little Frida looks very peaky. Much lovefrom Harold who is always asking when you're coming home. Mama is verywell, I'm glad to say.

Your affectionate sister,

HILDA CURTIS.

"She might have told me a little more about the house," John murmured tohimself. And then he began to dream about Ambles and to plantold-fashioned flowers along its mellow red-brick garden walls. "I shallbe in time to see the colouring of the woods," he thought. The_Murmania_ answered his aspiration with a plunge, and several of therumpled ladies rose hurriedly from table to prostrate themselves for therest of the voyage. John opened a fourth letter from England.

THE VICARAGE,

Newton Candover, Hants,

_October 7_.

MY DEAREST JOHN,--I was so glad to get your letter, and so glad to hearof your success. Laurence says that if he were not a vicar he shouldlike to be a dramatic author. In fact, he's writing a play now on aBiblical subject, but he fears he will have trouble with the Bishop, asit takes a very broad view of Christianity. You know that Laurence hasrecently become very broad? He thinks the village people like it, butunfortunately old Mrs. Paxton--you know who I mean--the patroness of theliving--is so bigoted that Laurence has had a great deal of trouble withher. I'm sorry to say that dear little Frida is looking thin. We thinkit's the wet summer. Nothing but rain. Ambles was looking beautiful whenwe drove over last week, but Harold is a little bumptious and Hilda doesnot seem to see his faults. Dear Mama was looking _very_ well--betterthan I've seen her for ages. Frida sends such a lot of love to dearestUncle John. She never stops talking about you. I sometimes get quitejealous for Laurence. Not really, of course, because family affection isthe foundation of civil life. Laurence is out in the garden speaking toa man whose pig got into our conservatory this morning. Much love.

Your loving sister,

EDITH.

John put the letter down with a faint sigh: Edith was his favoritesister, but he often wished that she had not married a parson. Then hetook up the last letter of the family packet, which was from hishousekeeper in Church Row.

39 CHURCH ROW,

_Hampstead, N.W._

DEAR SIR,--This is to inform you with the present that everythink isvery well at your house and that Maud and Elsa is very well as it leavesme at present. We as heard nothink from Emily since she as gone down toHambles your other house, and we hope which is Maud, Elsa and myself youwont spend all your time out of London which is looking lovely atpresent with the leaves beginning to turn and all. With dutiful respectsfrom Maud, Elsa and self, I am,

Your obedient servant,

MARY WORFOLK.

"Dear old Mrs. Worfolk. She's already quite jealous of Ambles ...charming trait really, for after all it means she appreciates ChurchRow. Upon my soul, I feel a bit jealous of Ambles myself."

John began to ponder the pleasant heights of Hampstead and to think ofthe pale blue October sky and of the yellow leaves shuffling andslipping along the quiet alleys in the autumn wind; to think, too, ofhis library window and of London spread out below in a refulgence ofsmoke and gold; to think of the chrysanthemums in his little garden andof the sparrows' chirping in the Virginia-creeper that would soon be allaglow like a well banked-up fire against his coming. Five delightfulletters really, every one of them full of good wishes and cordialaffection! The _Murmania_ swooped forward, and there was a faint tingleof glass and cutlery. John gathered up his correspondence to go on deckand bless the Atlantic for being the pathway to home. As he rose fromthe table he heard a voice say:

"Yes, my dear thing, but I've never been a poor relation yet, and Idon't intend to start now."

The saloon was empty except for himself and two women opposite, theclimax of whose conversation had come with such a harsh fitness ofcomment upon the letters he had just been reading. John was angry withhimself for the dint so easily made upon the romantic shield he upheldagainst life's onset; he felt that he had somehow been led into anambush where all his noblest sentiments had been massacred; five bellssounded upon the empty saloon with an almost funereal gravity; and, whenthe two women passed out, John, notwithstanding the injured regard ofhis steward, sat down again and read right through the family lettersfrom a fresh standpoint. The fact of it was that there had turned out tobe very few currants in the cake, for the eating of which he hadprepared himself with such well-buttered bread. Few currants? There wasnot a single one, unless Mrs. Worfolk's antagonism to the idea of Amblesmight be considered a gritty shred of a currant. John rose at once whenhe had finished his letters, put them in his pocket, and followed theunconscious disturbers of his hearth on deck. He soon caught sight ofthem again where, arm in arm, they were pacing the sunlit starboard sideand apparently enjoying the gusty southwest wind. John wondered how longit would be before he was given a suitable opportunity to make theiracquaintance, and tried to regulate his promenade so that he shouldalways meet them face to face either aft or forward, but never amidshipswhere heavily muffled passengers reclined in critical contemplation oftheir fellow-travellers over the top of the last popular novel. "Somemen, you know," he told himself, "would join their walk with a mereremark about the weather. They wouldn't stop to consider if theircompany was welcome. They'd be so serenely satisfied with themselvesthat they'd actually succeed ... yes, confound them ... they'd bring itoff! Yet, after all, I suppose in a way that without vanity I mightpresume they _would_ be rather interested to meet me. Because, ofcourse, there's no doubt that people _are_ interested in authors. But,it's no good ... I can't do that ... this is really one of those momentswhen I feel as if I was still seventeen years old ... shyness, I suppose... yet the rest of my family aren't shy."

This took John's thoughts back to his relations, but to a much lesscomplacent point of view of them than before that maliciously appositeremark overheard in the saloon had lighted up the group as abruptly andunbecomingly as a magnesium flash. However inconsistent he might appear,he was afraid that he should be more critical of them in future. Hebegan to long to talk over his affairs with that girl and, looking up atthis moment, he caught her eyes, which either because the weather was sogusty or because he was so ready to hang decorations round a simple factseemed to him like calm moorland pools, deep violet-brown pools inheathery solitudes. Her complexion had the texture of a rose inNovember, the texture that gains a rare lucency from the grayness andmoisture by which one might suppose it would be ruined. She was wearinga coat and skirt of Harris tweed of a shade of misty green, and with herslim figure and fine features she seemed at first glance not more thantwenty. But John had not passed her another half-dozen times before hehad decided that she was almost a woman of thirty. He looked to see ifshe was wearing a wedding ring and was already enough interested in herto be glad that she was not. This relief was, of course, not at all dueto any vision of himself in a more intimate relationship; but merelybecause he was glad to find that her personality, of which

he was by nowmore definitely aware than of her beauty (well, not beauty, but charm,and yet perhaps after all he was being too grudging in not awarding herpositive beauty) would be her own. There was something distinctlyromantic in this beautiful young woman of nearly thirty leading her ownlife unimpeded by a loud-voiced husband. Of course, the husband mighthave had a gentle voice, but usually this type of woman seemed a prey tobluffness and bigness, as if to display her atmosphere charms she hadneed of a rugged landscape for a background. He found himself gliblythinking of her as a type; but with what type could she be classified?Surely she was attracting him by being exceptional rather than typical;and John soothed his alarmed celibacy by insisting that she appealed tohim with a hint of virginal wisdom which promised a perfect intercourse,if only their acquaintanceship could be achieved naturally, that is tosay, without the least suggestion of an ulterior object. _She had neverbeen a poor relation yet, and she did not intend to start being onenow._ Of course, such a woman was still unmarried. But how had sheavoided being a poor relation? What was her work? Why was she cominghome to England? And who was her companion? He looked at the other womanwho walked beside her with a boyish slouch, wore gold pince-nez, and hada tight mouth, not naturally tight, but one that had been tightened bydriving and riding. It was absurd to walk up and down forever like this;the acquaintance must be made immediately or not at all; it would neverdo to hang round them waiting for an opportunity of conversation. Johndecided to venture a simple remark the next time he met them face toface; but when he arrived at the after end of the promenade deck theyhad vanished, and the embarrassing thought occurred to him that perhapshaving divined his intention they had thus deliberately snubbed him. Hewent to the rail and leaned over to watch the water undulating past; asudden gust caught his cap and took it out to sea. He clapped his handtoo late to his head; a fragrance of carnations breathed upon the saltwindy sunlight; a voice behind him, softly tremulous with laughter,murmured:

"I say, bad luck."

John commended his deerstalker to the care of all the kindly Oceanidesand turned round: it was quite easy after all, and he was glad that hehad not thought of deliberately letting his cap blow into the sea.

"Look, it's actually floating like a boat," she exclaimed.

"Yes, it was shaped like a boat," John said; he was thinking how absurdit was now to fancy that swiftly vanishing, utterly inappropriate pieceof concave tweed should only a few seconds ago have been worn the otherway round on a human head.

"But you mustn't catch cold," she added. "Haven't you another cap?"

John did possess another cap, one that just before he left England hehad bought about dusk in the Burlington Arcade, one which in the velvetybloom of a July evening had seemed worthy of summer skies and seas, butwhich in the glare of the following day had seemed more like the shredsof barbaric attire that are brought back by travelers from exotic landsto be taken out of a glass case and shown to visitors when theconversation is flagging on Sunday afternoons in the home counties. Nowif John's plays were full of fierce hues, if his novels had been sepiastudies of realism which the public considered painful and the criticsdescribed as painstaking, his private life had been of a mild uniformpink, a pinkishness that recalled the chaste hospitality of the bestspare bedroom. Never yet in that pink life had he let himself go to theextent of wearing a cap, which, even if worn afloat by a coloredprizefighter crossing the Atlantic to defend or challenge supremacy,would have created an amused consternation, but which on the head of awell-known romantic playwright must arouse at least dismay and possiblypanic. Yet this John (he had reached the point of regarding himself withobjective surprise), the pinkishness of whose life, though it might be aprotest against cynicism and gloom, was eternally half-way to a blush,went off to his cabin with the intention of putting on that cap. Withhimself for a while he argued that something must be done to imprisonthe smell of carnations, that a bowler hat would look absurd, that hereally must not catch cold; but all the time this John knew perfectlywell that what he really wanted was to give a practical demonstration ofhis youth. This John did not care a damn about his success as a romanticplaywright, but he did care a great deal that these two young womenshould vote him a suitable companion for the rest of the voyage.

"Why, it's really not so bad," he assured himself, when before themirror he tried to judge the effect. "I rather think it's better thanthe other one. Of course, if I had seen when I bought it that the checkswere purple and not black I dare say I shouldn't have bought it--but, byJove, I'm rather glad I didn't notice them. After all, I have a right tobe a little eccentric in my costume. What the deuce does it matter to meif people do stare? Let them stare! I shall be the last of the lot tofeel seasick, anyway."

John walked defiantly back to the promenade deck, and several people whohad not bothered to remark the well-groomed florid man before now askedwho he was, and followed his progress along the deck with the easilyinterested gaze of the transatlantic passenger.

For the rest of the voyage John never knew whether the attention hisentrance into the saloon always evoked was due to his being the man whowore the unusual cap or to his being the man who had written _The Fallof Babylon_; nor, indeed, did he bother to make sure, for he wasfortified during the rest of the voyage by the company of Miss DorisHamilton and Miss Ida Merritt and thoroughly enjoyed himself.

"Now am I attributing to Miss Hamilton more discretion than she's reallygot?" he asked himself on the last night of the passage, a stormy nightoff the Irish coast, while he swayed before the mirror in the creakingcabin. John was accustomed, like most men with clear-cut profiles, totake advice from his reflection, and perhaps it was his dramaticinstinct that led him usually to talk aloud to this lifelong friend."Have I in fact been too impulsive in this friendship? Have I? That'sthe question. I certainly told her a lot about myself, and I think sheappreciated my confidence. Yet suppose that she's just an ordinary youngwoman and goes gossiping all over England about meeting me? I reallymust remember that I'm no longer a nonentity and that, though MissHamilton is not a journalist, her friend is, and, what is more,confessed that the sole object of her visit to America had been tointerview distinguished men with the help of Miss Hamilton. The way shespoke about her victims reminded me of the way that fellow in thesmoking-saloon talked about the tarpon fishing off Florida ... famousAmerican statesmen, financiers, and architects existed quiteimpersonally for her to be caught just like tarpon. Really when I cometo think of it I've been at the end of Miss Merritt's rod for five days,and as with all the others the bait was Miss Hamilton."

John's mistrust in the prudence of his behavior during the voyage hadbeen suddenly roused by the prospect of reaching Liverpool next day. Theword positively exuded disillusionment; it was as anti-romantic as anotebook of Herbert Spencer. He undressed and got into his bunk; themotion of the ship and the continual opening and shutting of cabin doorsall the way along the corridor kept him from sleep, and for a long timehe lay awake while the delicious freedom of the seas was graduallyenslaved by the sullen, prosaic, puritanical, bilious word--Liverpool.He had come down to his cabin, full of the exhilaration of a last quickstroll up and down the spray-whipped deck; he had come down from a longand pleasant talk all about himself where he and Miss Hamilton had satin the lee of some part of a ship's furniture the name of which he didnot know and did not like to ask, a long and pleasant talk, cozilywrapped in two rugs glistening faintly in the starlight with salty rime;he had come down from a successful elimination of Miss Merritt, hiswhole personality marinated in freedom, he might say; and now the merethought of Liverpool was enough to disenchant him and to make him feelrather like a man who was recovering from a brilliant, a too brilliantrevelation of himself provoked by champagne. He began to piece togetherthe conversation and search for indiscretions. To begin with, he hadcertainly talked a great deal too much about himself; it was notdignified for a man in his position to be so prodigally frank with ayoung woman he had only known for five days. Suppose she had beenlaughing at him all

the time? Suppose that even now she was laughing athim with Miss Merritt? "Good heavens, what an amount I told her," Johngasped aloud. "I even told her what my real circulation was when I usedto write novels, and I very nearly told her how much I made out of _TheFall of Babylon_, though since that really was a good deal, it wouldn'thave mattered so much. And what did I say about my family? Well, perhapsthat isn't so important. But how much did I tell her of my scheme for_Joan of Arc_? Why, she might have been my confidential secretary by theway I talked. My confidential secretary? And why not? I am entitled to asecretary--in fact my position demands a secretary. But would she acceptsuch a post? Now don't let me be impulsive."

John began to laugh at himself for a quality in which as a matter offact he was, if anything, deficient. He often used to chaff himself,but, of course, always without the least hint of ill-nature, which isperhaps why he usually selected imaginary characteristics for genialreproof.

"Impulsive dog," he said to himself. "Go to sleep, and don't forget thatconfidential secretaries afloat and confidential secretaries ashore arevery different propositions. Yes, you thought you were being very cleverwhen you bought those rope-soled shoes to keep your balance on aslippery deck, but you ought to have bought a rope-soled cap to keepyour head from slipping."

This seemed to John in the easy optimism that prevails upon the bordersof sleep an excellent joke, and he passed with a chuckle through theivory gate.

The next day John behaved helpfully and politely at the Customs, andindeed continued to be helpful and polite until his companions of thevoyage were established in a taxi at Euston. He had carefully writtendown the Hamiltons' address with a view to calling on them one day, buteven while he was writing the number of the square in Chelsea he wasthinking about Ambles and trying to decide whether he should make a dashacross London to Waterloo on the chance of catching the 9:05 P.M. orspend the night at his house in Church Row.

"I think perhaps I'd better stay in town to-night," he said. "Good-by.Most delightful trip across--see you both again soon, I hope. You don'tadvise me to try for the 9:05?" he asked once more, anxiously.

Miss Hamilton laughed from the depths of the taxi; when she laughed, forthe briefest moment John felt an Atlantic breeze sweep through therailway station.

"_I_ recommend a good night's rest," she said.

So John's last thought of her was of a nice practical young woman; but,as he once again told himself, the idea of a secretary was absurd.Besides, did she even know shorthand?

"Do you know shorthand?" he turned round to shout as the taxi buzzedaway; he did not hear her answer, if answer there was.

"Of course I can always write," he decided, and without one sigh hebusied himself with securing his own taxi for Hampstead.