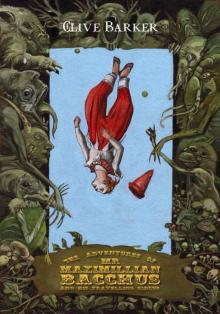

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

Clive Barker

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus

& His Traveling Circus

By Clive Barker

First Digital Edition published by Crossroad Press & Macabre Ink Digital

First published 2011 by Bad Moon Books

Copyright 2011 by Clive Barker

Artwork Copyright 2011 by Richard A.Kirk

LICENSE NOTES:

This eBook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This eBook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return the vendor of your choice and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Visit Bad Moon Books on the Web

BUY DIRECT FROM CROSSROAD PRESS & SAVE

Try any title from CROSSROAD PRESS – use the Coupon Code FIRSTBOOK for a one time 20% savings! We have a wide variety of eBook and Audiobook titles available. Find us at: http://store.crossroadpress.com

FOR RIVER CLIVE HUMPHREYS

THE FOOL RISES

Memories can be treacherous. We all have a hunger to rearrange our histories so as to remember ourselves in the most flattering light. This is not only true of individuals, but of entire areas of human activity; most notably the three human obsessions which are often elevated by the labors of careful historians so as to seem more worthy of our attentions. War, for instance; a very fine subject for carefully crafted censorship, as is Love, whether it be in the particular (our private histories) or the general (our public infamies). But it is with the third of these subjects, Art, that the subtle genius of human self-delusion is most prettily displayed. Where, after all, are we most likely to see fruitful creation than in the re-forging of the facts surrounding that very endeavour?

All this by way of an apology of sorts than for any errors that may have stowed away on this modest little vessel of mine, which intends only to explain how the stories in this volume came into being. In truth the book would have been carrying a larger number of stowaways than of passengers were it not for the irritatingly well-informed Phil and Sarah Stokes, who conspired several times to prevent my bringing of a few fact-free bon-bons on board. As I now know to my cost, Phil and Sarah know a lot more about me than I do, and shamelessly used the Truth to persuade me to throw several harmless fictions overboard. Has it not come to a sad state of things? When a man can't even lie about himself without being called to account? But there we have it.

One day, perhaps, The One True Tale concerning how this quartet of little fables came to be written will be gathered together, told by those who experienced them rather than by me. But this is not that time. You instead have before you the labours of a chastised fictioneer, obliged to slaughter his bastard lies to favour far less beguiling truths.

~ * ~

I have one last anarchic card up my sleeve, however. Rather than attempt to trace my own place as Creator I have chosen instead to focus on one of the characters from the stories and use him as a guide. That character is Domingo de Ybarrondo. Domingo is the clown in Mr. Bacchus' Travelling Circus; a creature whose adventures could only take place in a world where the rules of life and death are very different from those of our world.

It was, however, here in this version of the Real, that I first met Domingo. It was a chance encounter. In my teenage years I spent many hours, whatever the season, out on the streets of Liverpool, wandering. It was my second favorite hobby. I always had plenty to think about - paintings I would one day paint, stories I would one day write. On an early spring day in - let's say 1969 - I was walking down Aigburth Road when I caught sight of Domingo over a wall. No conversation passed between us. The man was dead and buried. It was simply his name engraved on a 19th Century headstone that had caught my eye. What drew me to the overgrown plot where he lay was simply the music of his name. Domingo de Ybarrondo. It has a fine, poetic ring to it. It carries with it, at least to me, the smell of somewhere balmy and strange.

Why I should have decided this wonderful name best belonged to a clown I have no idea. What I do know is that I have never found clowns remotely funny. I am not alone in this, I think. More people find clowns disturbing or distressing rather than raucously amusing. Is it that the nature of human existence has changed so radically in the last century or so that what was funny to our grandparents and great-grandparents is now tragic or terrifying? I don't have a clear answer, I only know that at some point in the writing process the name on the gravestone was born again, as a droll funnyman on a road in my mind's eye.

~ * ~

Until my early twenties my experience of clowns was very limited. I remember going just once to the circus as a child, though we went several times to see the parade as the circus came to town. It was a surreal spectacle in the late fifties, when Liverpool was still a grey, forbidding city. But many of the forms and faces of Domingo's dynasty became available to me once I discovered the work of Federico Fellini. As any Fellini enthusiast will tell you, his movies are filled with clowns of every kind, from the formal duo of the trumpet-playing Silver Clown and the ever-humiliated Auguste, to the countless Clowns Disguised As Human Beings who appear in all of his later movies. Once I had seen clowns through Fellini's eyes I was besotted. Here was a universal figure, upon which all manner of human experience (very little of it funny) could be attached. Inspired by Fellini's explorations I went off to my own stories of foolery and wisdom. Two plays that were written and produced long before THE BOOKS OF BLOOD gave me a reputation as a purveyor of visceral horrors. These plays are largely concerned with fools. The major piece is CRAZYFACE, which is definitely set in a world close to that of the Bacchus tales.

But it isn't only as a clown that Domingo de Ybarrondo appears in my fiction. And it's here that my opening comment about the rewriting of our histories comes round to show a different face. In the late 1980's I wrote a book called CABAL, which concerned itself with a small community of outsiders who are angels to some, demons to others. I decided it would be entertaining to preface each of the parts with a poem or essay which was relevant to the contents, as I had in the last novel I had written, WEAVEWORLD. In WEAVEWORLD the philosopher Francis Bacon and the poets W.B. Yeats and Robert Frost are amongst the writers I quote. By the time I wrote CABAL, however, I was in a more anarchic mood. I decided to invent my own authors and write my own quotes (thus insuring that they would be relevant).

It was immense fun.

Obviously, when I wrote CABAL, I had no thought to publishing the stories of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and his Travelling Circus. But it seemed sad to leave that beautiful, evocative name on a grimy headstone in an unremarkable Liverpool churchyard. So, at the beginning of the book, in pride of place, I put the name of Domingo de Ybarrondo.

Since his years travelling the invented roads of the stories that follow these pages, however, Domingo had left the circus and turned his hand to writing a book of his own. It was called, I supposed, A BESTIARY OF THE SOUL, and the quote that I had chosen from that learned tome really brings the whole story full circle.

~ * ~

"We are all imaginary animals..."

~ * ~

Those, I decided, were the words that Domingo de Ybarrondo had written, and which I chose to introduce the book about the shunned and the outlawed species of which I, as a gay man, felt myself a member.

Domingo's quote, like several others in the book, was accepted without question as a legitimate

quote from a legitimate source. Indeed, several critics referred to the book as though they were familiar with it.

I'd like to think that somewhere a clown is laughing.

Clive Barker

January, 2009

Los Angeles

THE WEDDING OF

INDIGO MURPHY

TO THE DUKE

LORENZO DE VEDICI

and how Angelo was discovered in an orchard

~ * ~

"Tiger, tiger, burning bright In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye Framed thy fearful symmetry?"

William Blake

This is the first story about Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and his Travelling Circus, and it concerns the wedding of Indigo Murphy to the Duke Lorenzo de Medici, and how Angelo was discovered in an orchard.

It was both a happy day and a sad day, the day that Indigo Murphy, who was the greatest bird-girl west of the Ochre Nile, married the Duke Lorenzo de Medici. It was happy because it was almost like the ending to some unwritten fairy-tale, and yet it was sad because, after all, Indigo had been one of the star attractions of Mr. Bacchus' Travelling Circus ever since it first took to the road. Now she was to be a Duchess, and live in her husband's palace, surrounded as it was by countless gardens laid out geometrically in the Babylonian style, in which stood white marble statues of gods metamorphosing into stags, and of square-bearded heroes in powdered wigs being bound by scorpions. She was even going to set all her performing birds free: her doves, her kittiwakes, the gulls, the humming birds and the kingfishers. Even the scaly Archaeopteryx, who was a gift from Perkin War-beck (who had practically been King of England), was to have his freedom today.

The wedding feast itself was held, at Indigo's request, in the middle of a field, outside the walls of the palace. It was the middle of September, the sixteenth, a Tuesday, and the weather was still pleasant to sit out in. The deep blue of the late Summer sky was here arid, there veiled with lace clouds, and a light wind washed through the grass like a tide, sighing in the rows of severely-pruned poplars that lined the shadowed walks of the walled gardens. From the palace itself, its roofs crowded with gargoyles, turrets, chimneys and carved gables, processions of servants were continually emerging, carrying silver trays upon which the Medici cooks had laid their most mouth-watering delicacies: Swan in Laburnum, Truffles, Hedge pig, Black pudding and Love-in-Disguise. Lorenzo the Duke had of course invited his many hundreds of friends and relatives to the wedding; his brother Giulano, Poliziano the poet, Botticelli the painter, Savonarola, his Aunts and Uncles, first cousins, second cousins and so on, as far as his most distant relations. There were Arab princes, who had made the journey from their billowing red tents in the livid sands of the burning Kalahari to attend the celebrations. Indigo, however, had only the other members of the Circus to invite, because, as she had always said:

"Friendship is like butter, me darlins; it's no use if you spread it too thinly."

At the longest of the tables sat the bride and bridegroom themselves, with the Duke's relatives on one side, and the members of the Circus on the other.

There was Hero, whose real name was Hieronymous, the strong man, who had painted Mr. Bacchus' caravan with pink fountains and salamanders turning cartwheels. He was wearing his best bow tie and loincloth, and sketching fishes on the tablecloth with a piece of charcoal. Next to him, perched upon her seat like a willow-leaf on water, sat Ophelia, the trapeze-girl, head to one side, sniffing her posy of mandrake roots. Then came Malachi, the crocodile who sang excerpts from opera at the Circus, his greatest achievement being "Brunnhilde's Immolation" from "Gotterdammerung," which he had performed before the Dream King in Neuschwanstein. Beside him, cross-legged on his chair, squatted Domingo de Ybarrondo, the Clown, balancing three pieces of priceless Venetian glass, one upon the other, on his aquiline nose, a wide grin on his flour-pale face. Finally, next to Lorenzo himself, sat Mr. Bacchus, a gentleman of considerable girth, with a swollen nose and a large, tightly curled grey beard entwined with dead vine leaves. As usual, he was wearing his much-abused top hat, and was reclining in his ancient wicker chair, sipping red wine and smiling from ear to ear. His wooden stick, which sprouted flowers as the mood took it; wild roses or convolvulus, was beside him. Today it was rosemary.

"For remembrance," said Ophelia.

Nobody knew from where exactly Mr. Bacchus came, nor, if the truth were known, where he was going. He had just appeared one bleak November morning, driving his caravan drawn by the giant Ibis-bird, Thoth. He had, it appeared, travelled the flat earth from one edge to the other. Even Lorenzo's distant cousins, who wandered the bleak Kalahari, where only the griffins rise complaining from their carrion, embraced him as a long-lost brother, and explained that in the past years he had frequently appeared from out of a sand storm upon a tortoise and dined upon marinated sand-eels with them.

At last, when the guests had eaten their way through five courses, and Domingo the Clown had broken two complete sets of priceless Venetian glass, Mr. Bacchus rose from his creaking chair, surveyed the elegant company for a moment, and then with his ringmaster's cough hushed the guests.

"My Lords," he began. "My Lords, Cardinals, Doctors of Divinity, Surgeons, Earls, Ladies and Gentlemen."

"And crocodiles," interjected Malachi.

"—and thou Leviathan," said Mr. Bacchus. "May I propose a toast? To the happy couple, Lorenzo and Indigo de Medici."

"Indigo and Lorenzo!" chorused the guests, raising what remained of the Venetian glass and drinking.

"I have the pleasure," continued Mr. Bacchus before anybody could sit down again, "of having known dear Indigo ever since she first began her professional career, in an act which is now, I'm sure you'll agree, justly acknowledged as the finest in the hemisphere. Why, I recall..."

"Oh Purgatory," said Hero, just beneath his breath, "it is the wedding speech."

Mr. Bacchus had a reputation for talking.

"—I recall," Mr. Bacchus went on, "the slip of a girl I came across down at the Dingle in the port of Liverpool, performing on the dock wall with a budgerigar. Since then she has gone from strength to strength, and has grown, quite frankly, into one of the most exquisite young ladies I have ever set eyes upon."

At this, Indigo smiled and looked down modestly. Botticelli began to clap—but Mr. Bacchus had not yet finished.

"Her act is quite simply the most charming I have ever seen. Why, no less an authority upon miracles than the late King Louis of France was magnanimous enough to invite us to Versailles—into the Hall of Mirrors itself—upon rumours he had heard of Indigo. And now, all too quickly, we must give the dear girl into the hands of her husband, Lorenzo the Magnificent, a poet, a farmer, a man of civilization and of carnival. We wish them both all happiness—"

Mr. Bacchus might have continued, but at this point stood Indigo herself, lifting her veil, brushing her red hair from her eyes, and stubbing out her cigar in her dinner.

"Mr. Bacchus—you're too kind, sure you are," she said, pausing momentarily to look at the other members of the Circus. "I'll never forget any of you, I swear I won't, and if me married life's as happy as me life on the road, sure I'll be as lucky as a frog with five legs. But now—I must be setting all my children free."

With a melancholy look, she left the table and, picking up her skirts in the manner of the elegant lady she was practicing to be, glided through the grass to the white box in which she kept her performing birds. As she approached it, from within there rose a cooing and shrieking, and she softly said:

"Hush, hush, me darlins. Murphy's here."

Then she knelt, unlatched the box and threw open the lid. In a cloud of alabaster and turquoise, the birds flew up out of the box into the sun, and one by one turned in the air and came down to land on Indigo's legs, shoulders and out-stretched fingers.

"It's time you was on your ways, me darlins," said Indigo, and she kissed each one of them lightly on the beak. "Farewell me pretties," she said. "You're f

ree, sure you are! Free as the wind of Liverpool Bay!"

By now the silence from the guests was punctuated by sniffs and blown noses, but Indigo did not seem to notice. She just launched her birds into the air, blowing kisses to them all the time. The curious flock flew high up into the air and then dipped behind the dark poplars in the palace grounds. In the cool silence of the shaded walks, the marble heroes in their powdered wigs ceased to struggle at the sound of their wings, and sunning lizards took fright. The breeze blew a little colder off the ocean. Then suddenly, with a sweep of flickering wings, they appeared once more from over the top of the trees, and, having hovered over the guests' heads for a few moments, returned to Indigo's shoulders, head and fingers.

"No! No!" she snapped. "You're supposed to fly off now! You're free!"

But the birds took no notice. Instead, they flew onto the tables and began to perform their tricks. The kingfishers paddled around in the punch bowls, and the terns picked up bunches of grapes and dropped them in Bacchus' lap, while the scaly Archaeopteryx plucked the hundreds of candles from the candelabras and systematically set fire to the tablecloths. The wine boiled in the chalices, and the roast swan took flight in flames. Screaming, the guests leapt up from their seats, as the fire consumed the wedding feast in their place, while the birds, squawking and cooing insanely, flew up above the flames and danced a wedding jig through the smoke. Except for the crackle of the burning tables and the din of the hysterical birds, there fell a horrid silence. The wedding celebrations were wrecked, the wine evaporated, the food devoured, the guests soaked in punch and filthy with smoke. Never had a Medici wedding been so ill-omened as this. Then, softly at first, from behind the leaping flames of the table, there began ripples of deep laughter, spreading through the silence. It was Mr. Bacchus. He laughed to see the ridiculous pomp brought low, to see the blue-blooded guests lose their dignity and walk on all fours like Nebuchadnezzar. Gradually, the tight-lipped faces of the guests softened, and the corners of their mouths began to twitch with smiles. Very soon they were all sitting in the tide of the grass, weeping with laughter. All except Indigo. She was furious.