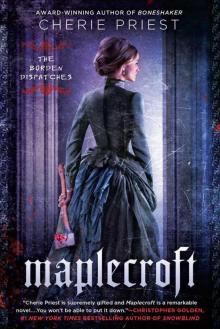

Maplecroft

Cherie Priest

Praise for Maplecroft

“Cherie Priest is supremely gifted and Maplecroft is a remarkable novel, simul- taneously beautiful and grotesque. It is at once a dark historical fantasy with roots buried deep in real-life horror and a supernatural thriller mixing Victorian drama and Lovecraftian myth. You won’t be able to put it down.”

—Christopher Golden, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Snowblind

“With Maplecroft, Cherie Priest delivers her most terrifying vision yet—a genuinely scary, deliciously claustrophobic, and dreadfully captivating historical thriller with both heart and cosmic horror. A mesmerizing, absolute must-read.”

—Brian Keene, Bram Stoker Award–winning author of The Rising and Ghoul

Praise for Cherie Priest and Her Novels

“Priest can write scenes that are jump-out-of-your-skin scary.”

—Cory Doctorow, author of Homeland

“Fine writing, humor, thrills, real scares, the touch of the occult . . . had me from the first page.”

—Heather Graham, New York Times bestselling author of The Night Is Forever

“Cherie Priest has created a chilling page-turner. Her voice is rich, earthy, soulful, and deliciously Southern as she weaves a disturbing yarn like a master! Awesome—gives you goose bumps!”

—L. A. Banks, author of the Vampire Huntress Legend series

“Wonderful. Enchanting. Amazing and original fiction that will satisfy that buttery Southern taste, as well as that biting aftertaste of the dark side. I loved it.”

—Joe R. Lansdale, award-winning author of The Thicket

“Priest masterfully weaves a complex tapestry of interlocking plots, motivations, quests, character arcs, and background stories to produce an exquisitely written novel with a rich and lush atmosphere.”

—The Gazette (Montreal)

“Priest has a knack for instantly creating quirky, likable, memorable characters.”

—The Roanoke Times (VA)

“Cherie Priest has crafted an intriguing yarn that is excellently paced, keeping the reader turning pages to discover where the story will lead.”

—San Francisco Book Review

“Priest’s haunting lyricism and graceful narrative are complemented by the solemn, cynical thematic undercurrents with a tangible gravity and depth.”

—Publishers Weekly

“With each volume, Priest squeezes in several novels’ worth of flabbergasting ideas, making each story expansive as hell while still keeping a tight control over the three-act structure.”

—The Chicago Center for Literature and Photography

“Cherie Priest has mastered the art of braiding atmosphere, suspense, and metaphysics.”

—Katherine Ramsland, bestselling author of Ghost: Investigating the Other Side

“Priest does an excellent job of building tension throughout the novel, in fact, up to and including the satisfying ending. Writing that can simultaneously set a mood, flesh out characters, and advance plot is a force to be reckoned with. With writing this good . . . I have no doubts that we will be hearing from Cherie Priest again and again.”

—SF Signal

“[Priest] is already a strong voice in dark fantasy and could, with care, be a potent antidote for much of what is lacking elsewhere in the genre.”

—Rambles

“Priest is amazing at detail, brilliant at transforming an imagined, impossible history in such a way that flying airships and a decades-long Yankee invasion seem not only plausible but simply neglected in our history books.”

—LitStack

“An engrossing and exciting adventure from its first sentence to its last. . . . Priest once again delivers a rousing adventure that demonstrates both her love of history and her definitive knack for playing with and bending it to fit the purpose of her captivating universe.”

—Bitten by Books

ROC

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Roc, an imprint of New American Library,

a division of Penguin Group (USA) LLC

Copyright © Cherie Priest, 2014

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA:

Priest, Cherie.

Maplecroft: the Borden dispatches / Cherie Priest.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-698-13838-4

1. Borden, Lizzie, 1860–1927—Fiction. 2. Fall River (Mass.)—Fiction. 3. Women murderers—Fiction. 4. Murder—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3616.R537M37 2014

813'.6—dc23 2014011172

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

Contents

Praise

Title page

Copyright page

Acknowledgments

THESE ARE THE THINGS AN EARTHQUAKE BRINGS: Lizzie Andrew Borden

A DOCTOR, A LAWYER, A MERCHANT, A CHIEF: Owen Seabury, M.D.

Phillip Zollicoffer, Professor of Biology, Miskatonic University

Lizzie Andrew Borden

BE SURE YOUR SINS WILL FIND YOU OUT: Owen Seabury, M.D.

I CROSS THE MAGPIE, THE MAGPIE CROSSES ME: Phillip Zollicoffer, Professor of Biology, Miskatonic University

Nance O’Neil

THIS KNOT I KNIT, THIS KNOT I TIE: Emma L. Borden

AND IF YOU HAVE A HORSE WITH ONE WHITE LEG . . .: Phillip Zollicoffer, Professor of Biology, Miskatonic University

THE WORST IS TO BE JUDGED WITHOUT HOPE: Owen Seabury, M.D.

Lizzie Andrew Borden

BUT NETTLE SHANT HAVE NOTHING: Nance O’Neil

CUT THEM ON FRIDAY, YOU CUT THEM FOR SORROW: Owen Seabury, M.D.

Phillip Zollicoffer, Professor of Biology, Miskatonic University

HAPPY IS THE CORPSE THAT THE RAIN SHINES ON: Owen Seabury, M.D.

A DWELLING PLACE OF JACKALS, THE DESOLATION FOREVER: Emma L. Borden

Lizzie Andrew Borden

Nance O’Neil

Emma L. Borden

Owen Seabury, M.D.

Lizzie Andrew Borden

RIGHT CHEEK, LEFT CHEEK—WHY DO YOU BURN?: Owen Seabury, M.D.

Aaron B. Stewart, Fire Chief, Farthington, Mass.

Emma L. Borden

Gerald Macintyre, Telegraph Clerk, Western Union

Owen Seabury, M.D.

Physalia, Z. University I Was Not Now

DEPART, ALL ANIMALS WITHOUT BONES: Owen Seabury, M.D.

Emma L. Borden

Owen Seabury, M.D.

Lizzie Andrew Borden

Owen Seabury, M.D.

Phillip Zollicoffer. Physalia Zollicoffris.

Christoff Dane, M.D., Ph.D., University of Rhode Island, Kingston

Emma L. Borden

Owen Seabury, M.D.

Emma L. Borden

FAMILY SLAIN IN MAYFIELD

Owen Seabury, M.D.

<

br /> Lizzie Andrew Borden

Emma L. Borden

Owen Seabury, M.D.

Lizzie Andrew Borden

Inspector Simon Wolf

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are always too many people to thank—and I always live in fear of leaving someone out, but books don’t come together without a hell of a team and I’m very lucky to have such wonderful folks on my side. So I will take a crack at it, and hope for the best.

First and foremost, thanks go to my editor, Anne Sowards, and all the fine folks at Ace/Roc, for taking a chance on this peculiar project of mine. I know it’s a little on the weird side, but I’m terribly proud of it—and I’m grateful beyond belief that Anne was willing to take a chance on it, and that all the great people at her office have done such a stellar job with the final product. Likewise (and along that same vein), thanks go to everyone at Donald Maass, particularly and especially my agent, Jennifer Jackson, for closing the deal and generally being a shoulder to cry on, a wall to bounce things off of, and a partner in storytelling crime.

And then, of course, thanks to the usual suspects: my husband, Aric, whose patience with these things knows no bounds; Warren Ellis and everyone in the secret clubhouse that serves the world; GRRM and the Consortium; Greg Wild-Smith for the long-term and long-suffering Web support; Team Capybara and all its affiliate members; the Nashville crew in all its awesomeness (dear Lees, Harveys, et al); the kindly souls at Woodthrush and Robin’s Roost; Bill Schafer, Yanni Kuznia, and the other assorted Michigan Maniacs; Paul Goat Allen at B&N (and everywhere else); Derek Tatum and Carol Malcolm for all the gossip and encouragement; and Maplecroft’s Chief Cheerleader, Christopher Golden. He knows why.

THESE ARE THE THINGS AN EARTHQUAKE BRINGS

Lizzie Andrew Borden

MARCH 17, 1894

No one else is allowed in the cellar.

Emma has a second key, in case I am injured or trapped down there; but Emma also has instructions about how and when to use that key. When she knocks upon the cellar door, I must always reply, “Emma dear, I’m nearly finished.” Even if I’m not working on anything at all. Even if I’m simply down there, writing in my journals. If I say anything else when she knocks, or if I do not respond—my elder sister knows what to do: She must summon Doctor Seabury, and then prevent him from descending into the cellar unarmed.

I wish there were someone closer she could send for, but no one else would come.

The good doctor, though . . . he could be persuaded to attend us, I believe. And he’s a large man, sturdy, and in good health for a fellow of his age. Quite a commanding presence, very much the old soldier, which is no surprise. During the War Between the States, he served as a field surgeon—I know that much. He must’ve been quite young, but the military training has served him well through the years, even in such a provincial setting as Fall River.

Yes, I think all things being equal, he’s the last and best chance either Emma or I would have, were either of us to meet with some accident. And between the two of us, I suppose it must be admitted—to myself, if no one else—that accidents are more likely to befall me than her.

Ah, well. I’d take up safer hobbies if I could.

I locked the cellar door behind myself, and proceeded down the narrow wood-slat stairs into the darkness of that half-finished pit, once intended for vegetables, roots, or wines. I’ve paid a pretty penny to refurbish the place so that the floor is stable and the walls are stacked with stone. During wet weather, those stones weep buckets and the floor creaks something awful, but by and large it’s secure enough.

Secure and quiet. Dreadfully so, as I’ve learned on occasion. I could scream my head off down there and Emma could be reading peacefully by the fireplace. She’d never hear a thing.

Obviously this concerns me, but what can I do? My precautions are for the safety and well-being of us both.

Of us all.

I lit the gas fixtures as I went. All three came on with a turn of their switches, and by the time I reached the final stair I cast a huge, long shadow—as if I were a giant in my own laboratory.

My laboratory. That feels like the wrong word, but what else can I call it? This is the place where I’ve gathered my specimens, collected my tools, recorded my findings, and meticulously documented all experiments and tests. So the word must apply.

I cannot claim to have made any real progress, except I now know a thousand ways in which I have failed to save anyone, anywhere. From anything.

It would be easier, I think, if I knew there was some finite number of possibilities—an absolute threshold of events I could try in order to produce successful, repeatable results. If I knew there were only a million hypothetical trials, I would cheerfully, painstakingly navigate them all from first to last. Such a task might take the rest of my life, but it’d be a comfort to know I was forcing some definite evolution to a crisis.

But I don’t know any such thing. And more likely, the possibilities measure in the billions—or are altogether endless. I shudder to consider it, but I’d be a fool if I didn’t.

So I go on wishing. I wish for the prospect of a definite finale, and I wish I were not alone.

That would make things easier, too—if there were someone else to share the burden, apart from poor Emma. And though she appeared invulnerably strong when I was a child (due in part to the ten-year difference in age between us), in our middling years her health has failed her in a treacherous fashion. Often she’s confined to a bed or a seat, and she coughs with such frequency that I only notice it anymore if she’s stopped. Consumption, everyone supposes. Consumption, and possibly the shock of what befell our father and Mrs. Borden.

That’s the rest of what everyone supposes, and that’s probably true, in its way. It’s true that Emma has never been herself since those last weeks when she fled the house, insisting that something was wrong and that she felt a hideous suffocation, and she needed to find some other air to breathe.

That’s how she put it. Finding other air to breathe.

At the time we assumed she only wanted a change of scenery from the fighting, the bickering, and the sudden appearance of William—and all the difficulties he inspired.

True, true. All of it true, but incomplete.

We were both contaminated by something, by whatever took the other Bordens. It worked its way inside us, too—whether by breath, or through the skin, or through something we consumed, still I cannot say. All I can do is pray that we caught it in time, and that we have removed ourselves beyond its influence . . .

Alas.

I almost wrote, “before any permanent damage was done.” But then I thought of Emma and her fragile lungs, and her bloodied handkerchiefs. And I thought also of my poisoned dreams and the awful visions that sometimes distract me even while waking. I often believe in retrospect that they’re telling me something crucial . . . but doesn’t every dreamer insist that every dream is meaningful at the time? However, in the retelling, the dreams (and my visions) are trite at best, disturbing at worst.

I will not burden Emma with them, for she is burdened enough with her own body’s complaints. And I don’t have anyone else to tell, not really. Not except for Nance, and I fear to the point of fretful, bowel-clenching sickness that I might chase her away even without the secrets that darken the space between us. Little though I see her lately, since her most recent job for that director, Peter Rasmussen . . . still I value beyond my life the time I spend with her beside me.

Nance has accused me, once or twice in teasing, of being a sentimental old fool. She’s right, absolutely.

She’s also young—very young. So young it’s all the more inappropriate, how we carry on between ourselves. Carelessly, it’s been said. Wantonly, it’s been accused. Nance wouldn’t argue with either one; she would laugh instead, and add her own descriptors with even less propriety. But women her age, barely out of their teens and with the whole world before them, they haven’t yet had time to lose the things they love.

Every affair is a fairy tale or a tragedy, and either one is fine so long as the story is good. Every love is all or nothing, and even their “nothings” are poetry. They don’t yet know how the years fade and stretch the highs and the lows, wearing them thin, making them vulnerable. They haven’t yet known much of death.

I don’t think I’m talking about Nance anymore.

It doesn’t matter. She won’t come again for weeks, maybe months. And I won’t hold that against her.

I can’t. I’m the one who asked her to stay away.

• • •

Upon reaching the cellar’s floor I turned on the two largest gaslights, and the bleak, cluttered space was flooded with a quivering white light that joined the illumination from the stairs. I blinked against it. I set one hand on the nearest table and leaned there while my eyes adjusted, and when they did, I took a very deep breath and considered the week’s samples.

My laboratory is a large open room, undivided except by two rows of three tables each. Several of the tables are occupied by jars of assorted sizes, ranging from tubes as small as my thumb to bigger containers that could easily hold a loaf of bread. Floating within them in an alcohol solution are things I’ve collected over the last two years. Some are recognizable as varieties of ordinary ocean flora and fauna, and some are not. I’ve gathered plants, fish, sea jellies, crustaceans, and cephalopods by the score, and I’ve cataloged them all by their deformities. Some are laden with so many aberrations that it’s impossible to tell what the original species might have been; some have minor exterior problems, though these malformations often mask more obvious internal ones.

For example, one of my larger jars holds a brown octopus (octopus vulgaris) with two distinct heads and three extra tentacles. Upon a cursory dissection of it, I discovered that it also had twice the usual complement of hearts—which is to say six of them. Two of these hearts were pitiably underdeveloped, but distinct and bafflingly present.

I’ve also found fish with too many sets of gills, grotesquely oversized fins, or no eyes whatsoever. I’ve retrieved lobsters with three claws, with one claw, with no tail, or no legs. The story is much the same for simpler creatures, though the abnormalities are sometimes harder to spot.