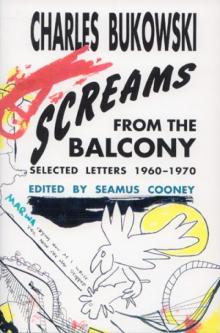

Screams From the Balcony

Charles Bukowski

CHARLES BUKOWSKI

SCREAMS FROM THE BALCONY

SELECTED LETTERS 1960-1970

EDITED BY

SEAMUS COONEY

Contents

Editor’s Note

• 1958 •

• 1959 •

• 1960 •

• 1961 •

• 1962 •

• 1963 •

• 1964 •

• 1965 •

• 1966 •

• 1967 •

• 1968 •

• 1969 •

Afterword

Searchable Terms

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Other Books by Charles Bukowski

Cover

Copyright

About the Publisher

EDITOR’S NOTE

The last thing this book needs is an academic introduction—so the few comments I have to offer will be the last thing, relegated to an Afterword.

All that’s required here is an explanation of how the letters have been edited. Working from photocopies of letters in private and public collections available to me, I have transcribed and selected roughly 50% of their contents. My only criterion was vividness and interest of the contents, while trying to minimize repetition. Except for three or four word changes, there has been no censorship or expurgation. Letters from the seventies and later will appear in a subsequent volume, where earlier letters found too late for printing here may also be included. Headnote comments about his correspondents are quoted from notes Charles Bukowski made at my request.

A few reproductions of letters (not all of them transcribed for inclusion) will let readers glimpse what this book cannot render: the total visual effect of many Bukowski letters, often decorated with drawings, painting, or collages. Not only are such visual components regrettably sacrificed, but making a readable text has also meant imposing some regularity on Bukowski’s spacing, spelling, and the like. There is no way these things could be fully preserved in setting type, in any case. And after a few instances (some of which I’ve preserved), typos grow distracting. But to give the flavor, I have presented a couple of representative letters verbatim and uncorrected.

Other editorial changes are regularizing of dates and the omission of most salutations and signoffs. For emphasis and for titles in his letters, Bukowski often typed in ALL CAPS. In a book these are hard on the eye. Here, when they are for emphasis, we print them as SMALL CAPS; when they name titles, we print them in regular title format: italics for books, quotes for separate poems or stories. I have indicated editorial omissions by asterisks in square brackets. A few editorial additions are similarly bracketed. A minimum of explanatory material has been included preceding some letters. References to Hank are to the biography of Bukowski by Neeli Cherkovski. “Dorbin” refers to Sanford Dorbin’s A Bibliography of Charles Bukowski (Black Sparrow, 1969).

The title for this volume was supplied by Charles Bukowski.

• 1958 •

In mid-1958, the time of the earliest letters available, Bukowski had recently begun working in the post office in a permanent position as a mail sorter, after an earlier spell of three years as a mail carrier. Not long before, he had resumed writing after a ten-year interval, and by now had a handful of little magazine publications. E. V. Griffith, editor of Hearse magazine, had agreed to do a chapbook. But the delay in publication was to test Bukowski’s patience to the limit. He finally received his author’s copies in October, 1960.

Until May 1, 1964, Bukowski’s letters are dated from 1623 N. Mariposa Avenue, Los Angeles 27, California.

(The following letter is printed in full.)

[To E. V. Griffith]

June 6, 1958

Dear E. V. Griffith:

Here are some more. Thanks for returning others. No title ideas yet. Post office pen no damn good. Trying to say—no title ideas yet.

Fire, Fist and Bestial Wail? No. Thought about using title of one of my short stories—“Confessions of a Coward and Man Hater.” No.

“The Mourning, Morning Sunrise.” No.

I don’t know, E. V.

I don’t know.

Anyhow, I’m thinking about it.

Sincerely,

Charles Bukowski

Gil Orlovitz (1918-1973) frequently published pamphlets of verse.

[To E. V. Griffith]

July 9, 1958

I still think Flower, Fist and Bestial Wail just about covers the nature of my work. If you object to this title I’ll send along some others.

I’m quite pleased with your selections. “The Birds,” which I had just written, I like personally but I found others would not like this type of thing because of its philosophical oddity. Poem, by the way, is factual and not fictional. All of my stuff you have is, except “59 and drinks” & “[Some Notes of Dr.] Klarstein.”

Thanks for sending Arrows of Longing.

As to Orlovitz, I find him at his best, very good. Certainly his delivery seems original.

Do you have my short stories about anywhere?

I suppose I mentioned I unloaded one at Coastlines and a couple at Views (Univ. of Louisville), but I think what you picked is pretty much my best stuff, and I have been honored to have been singled out by you and gathered up this way.

* * *

• 1959 •

Griffith published Carl Larsen’s Arrows of Longing as Hearse Chapbook no. 1 in 1958. He was also the editor of Gallows, in the first issue of which Bukowski had two poems printed.

[To E. V. Griffith]

August 10, 1959

Verification of existence substantiated.

I am alive and drinking beer. As to the literary aspect, I have appeared recently in Nomad #1, Coastlines (spring ’59), Quicksilver (summer ’59) and Epos (summer ’59). I haven’t submitted further to you because I have sensed that you are overstocked.

There are 10 or 12 other magazines that have accepted my stuff but as you know there is an immense lag in some cases between acceptance and publication. Much of this type of thing makes one feel as if he were writing into a void. But that’s the literary life, and we’re stuck with it.

I am looking forward, of course, to the eventual chapbook, and I hope it moves better for you than the Larsen thing. Of course, I don’t consider Carl Larsen a very good writer and am always surprised when anyone does. But to hell with Larsen, now where was I? Oh yes, I have never received a copy of Gallows and since you say I have a couple in it, I would like a copy. Could you send one down?

Well, there really isn’t much more to say…the horses are running poorly, the women are f/ruffing me up, the rent’s due, but as I said, I’m still alive and drinking beer. Glad to get your card. Don’t forget to send me to the Gallows. Thanx.

* * *

[To E. V. Griffith]

October 3, 1959

Dashing this off before going to the track with a couple of grifters. I hate these Saturdays—all the amateurs are out there with the greed glittering in their eyes, half-drunk on beer, pinching the women, stealing seats, screaming over nothing. [* * *]

Thanks for card and news of Hearse fame in Nation and Poetry (Ch.). Can’t seem to find the correct issue of Nation for this but am still trying. Success is wonderful if we can achieve it without whoring our concepts. Keep publishing the good live poets as in the past.

* * *

[To E. V. Griffith]

early December, 59

Are you still alive?

Everything that’s happening to me is banal or venal, and perhaps later a more flowery and poesy versification—right now drab and bare as the old-lady-in-the-shoe’s panties.

I don’t know, there’s o

ne hell of a lot of frustration and fakery in this poetry business, the forming of groups, soul-handshaking, I’ll print you if you print me, and wouldn’t you care to read before a small select group of homosexuals?

I pick up a poetry magazine, flip the pages, count the stars, moon, and frustrations, yawn, piss out my beer and pick up the want-ads.

I am sitting in a cheap Hollywood apartment pretending to be a poet but sick and dull and the clouds are coming over the fake paper mountains and I peck away at these stupid keys, it’s 12 degrees in Moscow and it’s snowing; a boil is forming between my eyes and somewhere between Pedro and Palo Alto I lost the will to fight: the liquor store man knows me like a cousin: he cracks the paper bag and looks like a photograph of Francis Thompson.

• 1960 •

Jory Sherman, described by Bukowski as “an early talent,” was a poet then living in San Francisco and publishing alongside Bukowski in little magazines like Epos, whose editor, Evelyn Thorne, suggested the two men should correspond (Hank, p. 116).

[To Jory Sherman]

[April 1, 1960]

Tell the staunch Felicia to hang on in: you are, to my knowledge, the best young poet working in America today. And rejections are no hazard; they are better than gold. Just think what type of miserable cancer you would be today if all your works had been accepted. The beef-eaters, the half-percepted wags who give you the pages and the print have forced you deeper in to show them the sight of light and color. [* * *]

Hell, if you want to read some of my poems, go ahead. I embrace you with luck. But I am tired of them, I am tired of my stuff, and I try very hard not to write anymore. I suppose I might sound like Patchen although I have not read much of him. Jeffers, I suppose, is my god—the only man since Shakey to write the long narrative poem that does not put one to sleep. And Pound, of course. And then Conrad Aiken is so truly a poet, but Jeffers is stronger, darker, more exploratatively modern and mad. Of course, Eliot’s gone down, Auden’s gone down, and William C. Williams has completely fallen apart. Do you think it’s age? And E. E. Cummings blanking out. Sherman’s coming on, though, taking them in the stretch, stride by stride, clomp, clomp, clomp, Sherman’s coming on toward the wire and the ugly crowd screams. Bukowski drinks a cheap beer.[* * *]

* * *

Sheri Martinelli, mentioned in this next and several subsequent letters, was an American artist for whose book Ezra Pound wrote an introduction: La Martinelli (Milan, 1956). Bukowski notes, “She wrote heavy letters, downgrading me. Everything was, ‘Ezra said…,’ ‘Ezra did…’ She was said to be a looker. I never met her. Lived in San Francisco.”

[To Jory Sherman]

[ca. April, 1960]

[* * *] Rather like Sheri M. altho when she sent back my poems she tried to relegate me with some rather standard formula and I had to take the kinks out of her wiring. [* * *] The Cantos make fine reading, the sweep and command of the langwidge (my spell) carries it even o’r the thin spots, although I have never been able to read the whole damn thing or remember what I’ve read, but it’s going to last, I guess, just for that reason: a well of Pounding unrecognized.

[* * *] Thanks again for Beat’d. Anonymous poem not good because guy thinks he can compromise life. There is no compromise: if you are going to write tv rifleman crap, tv rifleman crap will show in your poems, and if he thinks he’s an old timer at 34, he’d better towel behind the ears and elsewhere too, because Bukowski, who nobody’s heard of will be 40 on August 16th., and Pound who everybody’s heard of will be almost twice that old and has never compromised with anybody, nations or gods or gawkers and has signed his name to everything he has written, not for fame but for establishment of point and stance. Let the baker compromise, the cop and the mailman, some of us must hold the hallowed ground…[* * *]

* * *

“S & amp; S” is Scimitar and Song, whose March 1960 issue prints a Bukowski poem, with a typographical error.

[To Jory Sherman]

[ca. April, 1960]

[* * *] Do you double space your poems? I know that one is supposed to double space stories, articles, etc. for clarity and easy reading but thot poem due to its construction (usually much space), read easy enough singled. And I think a double-spaced poem loses its backbone, it flops in the air. I don’t know: the world is always sniping sniping so hard at the petty rules petty mistakes, I don’t get it, what doesn’t it mean? bitch, bitch, bitch. meanwhile the point going by: is the poem good or bad in your opinion? Rules are for old maids crossing the street.

Saw your poem in S & S. [* * *] She messed up my poem-eve instead of eye, but it was a rotter anyway. She’s a very old woman and prints the same type of poesy. Wrote me a letter about how the birds were chirping outside her window, all was peace, men like me who liked to drink and gamble, oh talented but lost. I saw a bird when I was driving home from the track the other day. It was in the mouth of a cat crouched down in the asphalt street, the clouds overhead, the sunset, love and God overhead, and it saw my car and rose, cat-rose insane, stiff back like mad love depravity, and it walked toward the curbing, and I saw the bird, a large grey, flip broken winged, wings large and out, dipped, feathers spread, still alive, cat-fanged; nobody saying anything, signals changing, my motor running, and the wings the wings in my mind and the teeth, grey bird, a large grey. Scimitar and Song, yes indeed. Shit. [* * *]

* * *

The poem “Death Wants More Death” was published in Harlequin in 1957. Sherman must have proposed reading it aloud to an audience.

[To Jory Sherman]

[Spring 1960]

[* * *] On “D. Wants More D.,” I am afraid it would disturb an audience a bit too much. My father’s garage had windows in it full of webs, flies and spiders churning blood-death in my brain, and tho I’m told nature has its meaning, I’m still infested with horror, and all the charts and graphs of the chemists and biologists and anthropologists and naturalists and sound-thinking men are nothing to the buzzing of this death.

* * *

“Crews” is Judson Crews, since 1949 a prolific author of books and pamphlets from the little presses.

[To E. V. Griffith]

April 25, 1960

No, I haven’t seen any of the Crews clip-out type production, and know very little of the mechanics of this sort of thing. But does this mean that a poem must have been published elsewhere in some magazine before it can be included in the chapbook? On much of my published work I only have one magazine and I would not care to tear them up for the chapbook. And you also hold much work of mine that has never been published. I don’t quite know; it is all rather puzzling. And I know that if we had to go after the missing magazines to get the clips it would take long long months, and perhaps many of them could never be acquired.

I wish you could write me a bit more on how this works, for as you can see I am mixed up. What would it cost some other way? Or do they have to be published pieces?

The prices seem fair enough and I could go up to the 32 pages if you have enough material to fill them. Perhaps we might add the 2 poems out of San Francisco Review #1, and I have some stuff coming out in the Coastlines and Nomad, due off the press any day now, I’m told. I don’t know if you’ll like it or not. And you’ve probably seen some of my other crap around. I think “Regard Me” in Nomad #1 was pretty good, but it’s hard for me to judge my own work and I’d rather leave that task up to you.

Right now I don’t know how many pages you can fill or just whether or not this clip-out method restricts the filling. So I guess we’ll have some more delay while you are kind enough to write me and fill in my ignorance.

Hoping to hear from you soon,

* * *

[To E. V. Griffith]

June 2, 1960

Good of you to write or even think chapbook while auto-torn. Like your lineup of poems ok, and should they run into more pages, please do let me know and I will money order you the difference. I would rather send you more than have you cut out a poem you want in there bu

t are restricted on pages. I guess it’s pretty hard to tell how many pages the thing will run at a loose glance like that and you will probably find out from your printer. Let me know how things work out this way on the pages. [* * *]

I just hope you can move a few copies so you won’t get stung too badly on your end of the deal. I have visions of chapbooks stacked in a closet gathering dust and nobody knowing Bukowski and Griffith are alive and I begin to have horrible qualms. Maybe not. Maybe if this works out ok, sometime in the future we can go in on another half and half deal. It seems very reasonable since you do all the work and are promoting another person’s work and not your own. The money end, from my side of it, seems less than nothing, but I realize that from your end with so many things going, different mags, chapbooks, it can get very very big, mountain-like. Well, hope all is ok, and you needn’t write for a while, I realize you are in tough shape—unless you have some suggestions or et al. I feel pretty good that this thing is going thru, although it’s hard to finally realize. [* * *]