Julia's Chocolates

Cathy Lamb

JULIA’S CHOCOLATES

JULIA’S CHOCOLATES

CATHY LAMB

KENSINGTON BOOKS

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

For my parents:

Bette Jean (Thornburgh) Straight

1941–2002

and

James Stewart Straight

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Epilogue

1

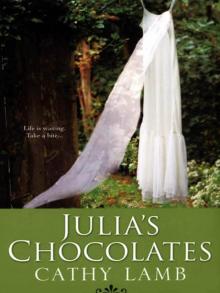

I left my wedding dress hanging in a tree somewhere in North Dakota.

I don’t know why that particular tree appealed to me. Perhaps it was because it looked as if it had given up and died years ago and was still standing because it didn’t know what else to do. It was all by itself, the branches gnarled and rough, like the top of someone’s knuckles I knew.

I didn’t even bother to pull over as there were no other cars on that dusty two-lane road, which was surely an example of what hell looked like: You came from nowhere; you’re going nowhere. And here is your only decoration: a dead tree. Enjoy your punishment.

The radio died, and the silence rattled through my brain. I flipped up the trunk and was soon covered with the white fluff and lace and flounce of what was my wedding dress. I had hated it from the start, but he had loved it.

Loved it because it was high-collared and demure and innocent. Lord, I looked like a stuffed white cake when I put it on.

The sun beat down on my head as I stumbled to the tree and peered through the branches to the blue sky tunneling down at me in triangular rays. The labyrinth of branches formed a maze that had no exit. If you were a bug that couldn’t fly, you’d be stuck. You’d keep crawling and crawling, desperate to find your way out, but you never would. You’d gasp your last tortured breath in a state of utter confusion and frustration, and that would be that.

Yes, another representation of hell.

The first time I heaved the dress up in the air, it landed right back on my head. And the second time, and the third, which simply increased my fury. I couldn’t even get rid of my own wedding dress.

My breath caught in my throat, my heart suddenly started to race, and it felt like the air had been sucked right out of the universe, a sensation I had become more and more familiar with in the last six months. I was under the sneaking suspicion that I had some dreadful disease, but I was too scared to find out what it was, and too busy convincing myself I wasn’t suicidal to address something as pesky as that.

My arms were weakened from my Herculean efforts and the fact that I could hardly breathe and my freezing-cold hands started to shake. I thought the dress was going to suffocate me, the silk cloying, clinging to my face. I finally gave up and lay facedown in the dirt. Someone, years down the road, would stop their car and lift up the pile of white fluff and find my skeleton. That is, if the buzzards didn’t gnaw away at me first. Were there buzzards in North Dakota?

Fear of the buzzards, not of death, made me roll over. I shoved the dress aside and screamed at it, using all the creative swear words I knew. Yes, I thought, my body shaking, I am losing my mind.

Correction: mind already gone.

Sweat poured off my body as I slammed my dress repeatedly into the ground, maybe to punish it for not getting caught in one of the branches. Maybe to punish it for even existing. I finally slung the dress around my neck like a noose and started climbing the dead tree, sweat droplets teetering off my eyelashes.

The bark peeled and crumbled, but I managed to get up a few feet, and then I gave the white monstrosity a final toss. It hooked on a tiny branch sticking out like a witch’s finger. The oversized bodice twisted and turned; the long train, now sporting famous North Dakota dirt, hung toward the parched earth like a snake.

I tried to catch my breath, my heart hammering on high speed as tears scalded my cheeks, no doubt trekking through lines of dirt.

I could still hear the dressmaker. “Why on earth do you want such a high neckline?” she had asked, her voice sharp. “With a chest like that, my dear, you should show it off, not cover up!”

I had looked at my big bosoms in her fancy workroom, mirrors all around. They heaved up and down under the white silk as if they wanted to run. The bosoms were as big as my buttocks, I knew, but at least the skirt would cover those.

Robert Stanfield III had been clear. “Make sure you get a wide skirt. I don’t want you in one of those slinky dresses that’ll show every curve. You don’t have the body for that, Turtle.”

He always called me Turtle. Or Possum. Or Ferret Eyes. If he was mad he called me Cannonball Butt.

Although I can understand the size of my butt—that came from chocolate-eating binges—I had never understood my bosoms. They had sprouted out, starting in fifth grade and had kept growing and growing. By eighth grade I had begged my mother for breast-reduction surgery. She was actually all for it, but that was because all of her boyfriends kept staring at me. Or touching. Or worse.

The doctor, of course, was appalled and said no. And here I was, thirty-four years old, with these heaving melons still on me. Note to self: One, get money. Two, get rid of the melons.

But the seamstress couldn’t let go of them. “It’s your wedding day!” she snapped, her graying hair electrified. “Why do you want to hide yourself?”

I hemmed and hawed standing there, drowning in material so heavy I could hardly walk, and said something really sickening about loving old-fashioned dresses, but I could tell she didn’t believe me.

She stuck three pins in her mouth, her huge eyes gaping at me behind her pink-framed glasses. “Humph,” she said. “Humph. Well! I’ve met your fiancé.” Her tone was accusatory. As if he were a criminal.

“Yes, well, then, you know his family is a very old Boston family, and they have a certain way.” I tried to sound confident, slightly superior. Robert’s mother was brilliant at that. Brilliant at making people feel like slugs.

“Very old, snobby family,” the dressmaker muttered. “And that mother! Talk about a woman with a stick up her butt!” She tried to say that last part quietly, but I heard her. “Well, fine, dear. That’s the way you want it, then?”

Again, she pierced me with those sharp owl eyes, and I couldn’t move, caught like a trapped mouse who knew she would soon be eaten, one bite at a time.

She dropped her hands. “You’re sure?” The words came out muffled through all those pins. “Very sure?”

“Yes, of course.” And inside me, that’s when the real screaming started. Long, high-pitched, raw. It had been quieter for months before then—smothered—but, sometimes I could almost hear my insides crying. I had ignored it. I had a fiancé, finally, and I was keeping him.

I had dug my way out of trailer life and scrambled through school while working full time and battling recurring nightmares of my childhood. I had a decent job in an art museum. People actually thought—and this was the hilarious part—that I was normal. The rancid smell of poverty and low-class living had become but a whiff around me.

I tried to be proud of that.

At that point, the day the dressmaker fitted me, the weddi

ng was exactly two weeks away. Exactly two weeks later I was on the fly.

I bent again to the cracked earth and caught up a handful of dirt, heaving it straight up at the dress, sputtering when some of it landed back on my head.

I spit on the ground, wiping the tears off my face with my dirty hands, flinching when I pressed my left eye too hard, the skin still swollen. Damn. That had been the last straw. I was not going to walk down the aisle with a swollen, purple, bloodied eye.

Then everyone would know how desperate I was.

I whipped around on my heel to the car, then floored the accelerator, the old engine creaking in protest. My wedding dress flapped its good-bye like a ghost. Sickening.

Goodbye, dress, I thought, wiping another flood of tears away. I’m broke. I’m scared shitless. Inhaling is often difficult for me because of my Dread Disease. But I have no use for you, other than as a decoration on a dead tree in hell.

I was now headed for the home of my Aunt Lydia in Oregon. Everyone else in our cracked family (cousins and aunts and uncles) thinks she’s crazy, which means that she is the only sane one in the bunch.

Robert would come after me, but it would take him a while to find me, as my mother had run off again last week—with her latest boyfriend, to Minnesota—and would not be able to give him Aunt Lydia’s address. I almost laughed. Robert would feel so inconvenienced.

But he would come. Burning with fury and humiliation, he would come to eke out some sick, twisted punishment.

My hands shook. I gripped the steering wheel tighter.

Aunt Lydia is my mother’s older half sister. Although my mother decided to marry no less than five times, and have only one (unplanned) child, my aunt has never married or had children. She lives on a farm outside the small town of Golden, Oregon, in a rambling hundred-year-old farmhouse.

When I was a child, Lydia would pay for my plane ticket to come and see her during the summer for six weeks. It was the highlight of my life, a pocket of peace next to my mother’s rages and her boyfriends’ wandering hands and bunched fists.

Two years ago, before I met Robert, I visited Aunt Lydia. When I arrived she was standing in front of her home, hands on her hips, with that determined look on her face.

When I got close, she engulfed me in a huge hug, then another, and another. “The house is depressed, Julia!” she bellowed, which is the way she always talks. She never speaks at a normal volume; it’s always at full speed, full blast. Her long gray hair floated about her face in the light breeze. “It’s anxious. On edge. Sad. It needs cheering up!”

My suitcases were piled around me, and I was still clutching a gift to her, a large yellow piggy bank shaped like a pig. I knew she would love it.

“This house should be pink!” She jabbed a finger in the air. “Like a camellia. Like a vagina!”

That week we painted the house pink, like a camellia and a vagina, and the shutters white. “The door to this house must be black,” Aunt Lydia announced, her loud voice chasing birds from the tree. “It will ward off evil spirits, disease, and seedy men, and we certainly don’t need any of that, now, do we, darlin’?”

“No, Aunt Lydia,” I replied, nudging my glasses back up my nose. At the time I hadn’t had a date in four years, so even a seedy man might be interesting to me, but I did not say that aloud. My last date had asked me, in a sneaky sort of way, if I had any family money to speak of. When I said I didn’t, he excused himself to the bathroom, and I had picked up the check and left when it was clear he was gone for good.

We painted the front door black.

During my visit, people would come to a screeching halt in front of Aunt Lydia’s house, as usual. Not because it looked like a pink marshmallow, burned in the center, and not just because she has eight toilets in her front yard.

But let me tell you about the toilets. Two toilets are tucked under a fir tree, two are by the front porch, and the rest are scattered about on the grass. All of them are white, and during every season of the year Aunt Lydia fills them with flowers. Geraniums in the summer, mums in the fall, pansies in the winter, and petunias in the spring. The flowers burst out of those toilets like you wouldn’t believe, spilling over the sides.

She also built, with her farmer friend Stash, a huge, arched wooden bridge smack in the middle of her green lawn. The floor of the bridge is painted with black and white checks, and the rails are purple, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red. Yes, just like a rainbow.

But I think it’s what is under the trellises that has drivers screeching to a halt. Four trellises, to be exact, lined up like sentinels in the front yard, which are all covered with climbing, blooming roses during the summer. The roses pile one on top of another, dripping down the sides and over the top in soft pink, deep red, and virginal white. And underneath each of the trellises sits a giant concrete pig. Yes, a pig. Each about five feet tall. Aunt Lydia loves pigs. Around the neck of each pig she has hung a sign with the pig’s name. Little Dick. Peter Harris. Micah. Stash.

These are the names of men who have made her mad for one reason or another. Little Dick refers to my mother’s first husband and my father. His real name was Richard and he decided to leave when I was three.

It is my earliest memory. I am running down the street as fast as I can, crying, wetting my pants, the urine hot as it streams down my legs. My father is tearing down the street on his motorcycle after fighting again with my mother. The plate she threw at him cracked above his head on the wall, missing him by about an inch.

The dish was the last straw, I guess.

Within a week, another man was spending the night in our home. Soon he was Daddy Kevin. Followed by Daddy Fred. Daddy Cuzz. Daddy Max. Daddy Spike, and numerous other daddies. I have not seen my father since then, although I have heard that he was invited to be a guest in the Louisiana State Penitentiary.

The pig named Peter Harris is named after Peter Harris. He is a snobby bank teller in town who refused to take a four-dollar service charge off Aunt Lydia’s bank account and then explained the situation to her in a loud and slow voice as if she were a confused and dottery old woman. For her revenge, she simply asked her friend Janice, a concrete artist, to make her another giant pig and then hung the Peter Harris sign around his neck.

When the pigs were featured in a local newspaper, Peter Harris was plenty embarrassed and came out to the farm in his prissy bank suit and told Aunt Lydia to take down the sign.

“I…CAN’T…DO…THAT!” she said, nice and slow, at full volume, as he had done to her. “THE PIG LIKES HIS NAME AND WON’T ALLOW ME TO CHANGE IT.”

When Peter started to argue with her, she said, “YOU OBVIOUSLY DON’T UNDERSTAND THE SITUATION. DO YOU HAVE A RELATIVE WHO COULD EXPLAIN THIS TO YOU?”

He kept arguing, stupid man, and even reached for the sign around the five-foot-tall pig’s neck, but Aunt Lydia said again, “THERE ARE A LOT OF PEOPLE IN LINE TODAY. PLEASE, MOVE ALONG.”

Peter Harris got a little more peeved then and told Lydia he was going to sue her from this side of Wednesday to the next. His anger didn’t faze Aunt Lydia.

He was only about three feet away from her when she yelled, “I’LL BE RIGHT BACK,” and went inside and grabbed not one, but two rifles, and came out shooting. Peter Harris left. He went straight to the sheriff, but as the sheriff is one of Stash and Aunt Lydia’s best friends, he walked Peter Harris to the bar and bought him a few stiff ones, and that was that.

The pig named Micah was named after a skinny, gangly cousin of hers who had a penchant for Jack Daniels and loose women. He was a belligerent drunk who never worked but always had time to pester Aunt Lydia for money. One night when he’d been at the local bar too long, he accidentally crashed his car into her front porch. As she had just painted the front porch yellow with orange railings, that was the last straw.

Lydia dragged his body out of that beater, his head lolling to the side, and stripped him naked. Next she drew a short red negligee over his unconscious head, then hauled him

into her own truck. She dumped him off in the middle of a field right behind the town.

The gossip in town over gangly Micah in the red negligee didn’t subside for two weeks, and the little girls who found him and ran and got their mothers will never forget the sight. Micah woke up surrounded by giggling women and rough and tough farmers and townspeople who looked at him with disgust and pointed their guns at his personal jewels.

“We don’t need your type here, Micah,” Old Daniel said, who owned the gasoline station and had regular poker games in the back room.

“You’re disgustin’,” said Stace Grammar, who worked in a factory and had biceps the size of tree stumps. “Get out of this town. Next thing you know, you and your boyfriend will be demanding equal rights.” He shot off his gun six inches over Micah’s head. “Take it to the city, boy!”

Micah turned and ran as fast as he could through town to Aunt Lydia’s, his bottom jiggling out the back of that red negligee. He ignored people’s hoots, hollers, and another gunshot, revved up his truck, and zoomed out of town.

We have never seen Micah again.

Stash is the only man in town who can ever beat Aunt Lydia at poker—that’s why a pig has been named after him. No one will play with Aunt Lydia anymore unless she agrees to play for pennies only, except Stash.

Aunt Lydia says he cheats. Stash is a grizzled man with a white beard and a bald head who’s built like an ox. His eyes are always laughing, and every time he’s come over when I’ve been there, he brings me fruit or candy and gives Aunt Lydia a plant or a new herb for her windowsill. Twice now he’s brought her perfume.