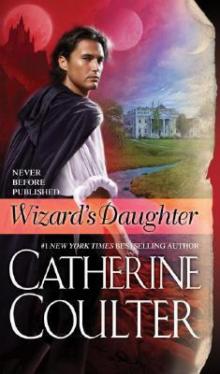

Wizard's Daughter

Catherine Coulter

Wizard's Daughter

Catherine Coulter

To Penelope Williamson

You're a wonderful writer and rider, and best of all, you're a wonderful friend.

-CC

1

A long time ago

I knew something wasn't right. I was lying on my back and I couldn't move. A single light shined directly onto my face, but it wasn't strong enough to blind me. The light was strange, soft and vague, and seemed to throb ever so slightly. "You are awake, I see."

A dark voice, a voice one would hear in the deepest part of the night; surely a man's voice, but unlike any I had ever heard before. Any normal man would be afraid of such a voice but, oddly, I found I was only mildly curious. I said, "Aye, I am awake. However, I cannot move."

"No, not yet. If you agree to do what I want, you will move again, as you did before I saved you and brought you to me."

"Who are you? Where are you?"

"I am behind the Cretan light. Lovely, is it not? Shim-mery as a king's silks, warm and soft as a woman's fingers tracing over your face.

"I saved your life, Captain Jared Vail. In return I ask a favor. Will you agree?"

"How do you know my name?"

The Cretan light—whatever that was—seemed to brighten a moment, and harden into a column of trapped flame, then soften once more, the glow gentle, pulsing like a resting heart. Did it believe I had insulted the being behind it? Its master, perhaps? No, that was ridiculous; a light, no matter what it did, was without breath or feeling, without a soul— was it not?

"Why can't I move?"

Where was the bloody man? I wanted to see his face, wanted to see the human who spoke all those words.

"Because I do not wish you to as yet. Will you grant me a favor for saving your life?"

"A favor? Do you wish me to kill someone? I have not dispatched a pirate or a thieving dock rat for three years." Where had that pathetic attempt at humor come from? There was no laugh, more's the pity, for that would have made the voice human, and perhaps that was why 1 had tried to jest. Still, I was not afraid, even though I knew in some part of my brain that I should be scared out of my few wits. But I was not.

"Who are you?" I asked again.

"I am your savior. You owe me your life. Are you willing to repay your debt?"

"I have gone from granting a favor to paying a debt."

"What is your life worth, Captain Jared Vail?"

"My life is worth all that I am. Will you let me live if I do not agree?"

The Cretan light -flashed bright blue for an instant, then flickered, as if brushed by a waving hand. Once again it settled. The shadows behind it remained impenetrable, like a black curtain covering an empty stage. My imagination was on fire. The voice brought me back. "Will I let you live? 1 do not know." A heavy pause. "I do not know."

'Then I have no choice, do I? I do not wish to die, al-though I would be well dead now had you not saved me. But I do not know how you managed it. The huge wave was on me, and the wound in my side—I would have died from that blow probably before the water crushed me."

I realized in that instant that I felt no pain from the gaping tear in my side that had hurled me into a madness of agony. I felt nothing at all except the strong, solid beating of my own heart, no stuttering with pain or fear, no gasping to find a breath.

"Ah, the pain. That is another debt you owe me, would you not agree?"

Why was I not afraid? The absence of fear made me feel cold to my soul. I was thinking it made me less a man, less— alive. Had he somehow removed my human fear? "How did you heal me?"

"I have many abilities," the black voice said, nothing more.

I retreated into my mind, trying to keep myself calm and focused, allowing no frightening stray thoughts to make me want to scream in terror, even though I knew any sane man would be babbling by now. He wanted me to pay him back for saving my life. I could certainly do that. But I asked, "I do not understand. You saved me in a way that no mortal could have saved me. If this is not an elaborate dream, if I am not dead, I would say you can do anything. What could I possibly do for you that you cannot do yourself?"

Cold silence stretched on and on. The Cretan light danced wildly, shooting off blue sparks that sprayed upward into the darkness, then suddenly there was calm. Was the light a mirror of my savior's feelings? The voice said, "I have sworn not to meddle. It is a curse that I must obey my own word."

"To whom have you sworn this?"

"You need not know that."

"Are you a man as I am a man?"

"Do I not speak incessantly as does a man, to hear the sound of his own voice? Did I not laugh like a man?"

Yes. No. "Will you tell me where I am?"

"It is not important, my friend."

His friend? If he was such a friend why could I not move?

Suddenly I felt my fingers. I wiggled them a bit, but still I could not raise my arm and that was surely alarming. Yet I wasn't alarmed, truth be told, merely interested and intrigued, as a man of science would be at the discovery of something unexpected. Had he seen the thoughts in my brain? Now, that gave me pause.

I said slowly, "What could a ship captain possibly do for you? You have demonstrated powers I cannot begin to imagine. I was aboard my brigantine in the middle of the Mediterranean, five miles from Santorini, my last port, and a huge wave appeared out of nowhere. I heard the screams of my sailors, heard my first mate yell to God to save him as that nightmare swell crashed over us. Then a splintered board speared into my side, tearing me open, and then the crushing mountain of water, and yet—"

"And yet you are here, warm, whole."

"My men? My ship?"

"They are dead, your ship destroyed. But you are not."

I thought of Doxey, my first mate, loud and crude, loyal to me and no one else, and Elkins, the cook, always singing filthy ditties, always making lumpy porridge everyone hated. I said, "Perhaps I am dead, perhaps you are the Devil and you are toying with me, amusing yourself, making me believe I am still alive, when I am really as dead as—"

A laugh. Yes, it was a laugh, low and strangely hollow, and something else—the laugh wasn't quite a man's laugh— it seemed to me it was more the imitation of a laugh. Was I in Hell? Would evil Uncle Ulson trip into my line of vision, ready to welcome die to his home? Why was I not afraid? Perhaps death removed a human's fear.

"I am not the Devil. He is a creature that is something else entirely. Will you pay your debt to me?"

"Yes, if I am actually alive."

I felt a bolt of pain so horrendous I would have welcomed death as a savior. My side gaped open; I could feel my flesh ripped away to my bones. I felt my guts oozing out of my belly. I screamed into the blackness. The Cretan light shot high, a wild mad blue. Then, as suddenly as it had started, the pain stopped. The Cretan light calmed.

"Did you feel your death blow from that falling beam?"

For a moment, I couldn't speak I was breathing so hard, bound in the memory of that ghastly agony. "Yes. I felt my own death but an instant away, so I must be dead, or—"

I heard amusement in that black voice, again somehow hollow, not quite right. "Or what?"

"If I am truly alive then you are a magician, a sorcerer, a wizard, though I am not at all certain there are grand differences amongst those titles. Or you are a being from above or below that a man of reason cannot accept. I know not and you will not tell me.

"You need me because you have promised not to meddle. Meddle? That is a curiously bloodless word, a word empty of threat or passion, like a promise a maiden aunt would make, is it not?"

"Will you pay your debt to me?"

I saw no hope for it. He was through with me. "Yes, I will pa

y my debt."

The Cretan light winked out. I was cast into darkness blacker than a sinner's heart. I was alone. But I had heard no retreating footfalls, no sound of any movement. There was no breathing in the still, black air but my own.

But what was my debt?

I fell asleep. I dreamed I sat at a grand table and ate a meal worthy of good Queen Bess herself, served by hands I could not see—roasted pheasant and other exotic meats, and dates and figs, and sweet flatbread I had never before eaten. Everything was delicious, and the tart ale from a golden flagon warmed my mouth and coursed through me like healing mother's milk. I was sated, I was content.

Suddenly the light in my dream shifted and a young girl appeared in front of me, hair red as the sunset off Gibraltar, loosely braided down her back. Her eyes were blue and freckles ran across her small nose. She seemed so real in that dazzling dream I felt I could reach out my hand and touch her. She threw her head back and she sang:

I dream of beauty and sightless night

I dream of strength and fevered might

I dream I'm not alone again

But I know of his death and her grievous sin.

A child's voice, sweet and true, it called forth feelings I had not known were in me, feelings to break my heart. But those strange words—what did they mean? Whose death? What grievous sin?

She sang the song again, more softly this time, and again her voice settled deep inside me as I listened to the strange minor key and the haunting sad notes that made me want to weep.

What did this small girl know of haunting or sin?

She went quiet. Slowly she took a step closer to me. Even though I knew this was a dream, I would swear I could hear her breath, hear her light footfalls. She smiled and spoke to me even as she seemed to fade into the soft air, and this time her words rang clear in my brain: I am your debt.

2

Pr esent A pril 22, 1835 London

Nicholas Vail stood at the edge of the large ballroom with its dozens of limp red and white silk banners hanging from the ceiling with military-precision distance between them—to give the feeling of a royal joust, don't you know, my lord, Lady Pinchon had said proudly, all puffed up with a purple turban on her head.

He agreed smoothly, mentioned it was a pity no knight and horse could fit into her magnificent ballroom, at which she looked very thoughtful.

He was sweating from the heat of all the too-close bodies and the countless numbers of dripping candles in every corner of the room. Of the long line of French doors that gave onto a large stone balcony, at least two were open to the still evening.

He pitied the women. They wore five petticoats—he'd counted them with the past several women he'd been with. He estimated there were two hundred women present, so that meant one thousand petticoats. It boggled the mind. And their gowns—the women looked like rich desserts in yards of heavy brocade or satin in every color invented by man, looped with braid and flounces that dusted the floor, wilted flowers and jewels in their hair—all of it had to weigh a good stone. He pictured the froth of petticoats in a mountainous pile in the middle of the ballroom, all those gowns dumped on top like frosting atop a cake, the lot sprinkled with the buckets of jewels that adorned their earlobes, necks, wrists. And that meant the women would be naked. Now, that was a fine picture to tease a man's brain. He saw one particularly heavy young matron, her chins quivering as she laughed, and quickly stifled that image.

As for the men, they looked dapper and prideful in their buttoned-up, nipped-in, long-tailed, proper black garb, starched and stiff, undoubtedly miserable in this heat. It made him shudder.

He knew exactly how they felt since he was dressed just as they were.

At least the women could bare half their chests, what with their gowns nearly falling off sloping white shoulders. He thought of walking around the ballroom, giving little tugs here and there to see what would happen. But those bare shoulders couldn't make up for those ridiculous Jong sleeves that stuck out so stiffly from their bodies. If he had to endure those sleeves, he would surely hunt down the insane misogynist who had foisted them on women. Were they supposed to make them more desirable? What they did was render each female a force to be reckoned with in sheer breadth.

It was time to get down to business. He raised his head, a wolf scenting prey. His hunt was over finally—she was here just as he'd known she would be—he felt her. The hair rose on his arms as the scent of her thickened in his nostrils. He turned quickly, nearly knocked the tray out of a footman's arms. He righted the footman, set his punch glass on the tray, and started toward her, pausing when he could finally see her face. She was young, obviously newly loosed on London, but he'd known she would be. She was laughing joyously, enjoying herself immensely. He could see her lovely white teeth flashing, her hair in thick braids stacked atop her head, making her look very tail indeed. As he drew nearer, he saw also that her pale blue satin gown didn't hang off sloping shoulders. Her shoulders didn't slope, but were strong, squared, her flesh as white as the beach sand on the leeward side of Coloane Island.

Her braids were dark red, a deep auburn it was written, perhaps Titian if one were a poet. It was she, no doubt in his mind at all. In odd moments over the years he'd wondered if he would die a doddering old man, not finding her, if it still wasn't the right time. But it was the right time and he was here and so was she. It was an unspeakable relief.

He walked toward her, aware that people were watching him; they usually did because he was an earl and no one knew a thing about him. London society loved a mystery, particularly if the mystery in question was an unattached presentable male with a title. There was his size too, one of his grandfather's gifts to him, and he knew he intimidated. With his black hair, pulled back and tied with a black velvet ribbon, he knew people looked at him and saw a man not quite civilized. They might have been right. He knew his eyes could turn cold as death, another gift from his grandfather—black eyes that made people think of wizards, perhaps, or executioners.

A couple danced into his path. He smoothly moved aside at the alarm on the man's face, but he scarcely noticed them, he was so focused on her.

Each of his senses recognized and accepted she was indeed the one he sought. She was waltzing now, her partner whirling her in wide circles, and her blue satin skirts swirled and ballooned around her. She was light on her feet, smoothly following her partner, an older man—old enough to be her father, only he wasn't paunchy and jowly like a father should be; he was tall and lean and graceful, his blue eyes bright as a summer sky, nearly the same light blue as hers, and that face of his was too handsome, his smile too charming. Her husband? Surely not, she was too young. He laughed at himself. Girls were married off at seventeen, some even sixteen, to men older than this one, who also looked fit and surely too spry for his age.

They danced by him. He saw her eyes were brighter than the gentleman's, she was that excited.

He stood quietly, watching. Around and around they whirled, the man keeping her to the perimeter so no one would dance into their path.

He could do nothing but wait, which he did, leaning negligently, arms crossed over his chest, against a wall beside a large palm tree that had a red bow fastened to one of its fronds. He didn't know her name, yet he already knew she wouldn't be a Mary or a Jane. No, her name would be exotic, but he couldn't ever think of a single English name exotic enough to fit his image of her.

He saw a pallid young gentleman and a lady who appeared to be his mother whispering as they looked toward him. He smiled at them, a black brow arching, not that he blamed them for their gossip. After all, he was the new Lord Mountjoy, and people were speculating on how he was adjusting to a title as empty as a gourd since the old earl had left all his wealth to Nicholas's three younger half brothers. All that was left to him was the entailed moldering family estate in Sussex, Wyverly Chase, built by the first Earl of Mountjoy, who had fought the Spanish like a Viking berserker and managed to charm the eternal vir

gin Queen Elizabeth. She had duly elevated Viscount Ashborough to his earldom. Wyverly Chase was going on three hundred years old, and showed every decade. As for the entailed three thousand acres, his father had ensured it was as worthless as a lack of money and care could make it by the time he'd died. His son was left with nothing but fallow fields, desperate tenants, and mountains of debt.

Was the young man's mama wondering where he'd come from? He'd heard one man whisper that the new earl was newly arrived from China. That made him smile.

Nicholas saw a man looking toward him, saw him say something to a portly man beside him. Was he speculating on whether Nicholas had yet met with his three half brothers, all young men now, two of them, he'd heard, as wild as any Channel storm? Ah, but most importantly, beggared as he was, had he come to London to find an heiress?

The music stopped, the waltz finally ended. Women smiled and laughed, waved themselves vigorously with dainty fans, gentlemen tried not to let anyone see how winded they were.

Nicholas watched the older man lead her to a knot of people standing on the opposite side of the ballroom.

It was time to do what he was supposed to do, time to do what he was meant to do.

3

He walked directly to the older man who'd danced with her, and bowed. "Sir, I am Nicholas Vail and I would like to dance with—" Nicholas stalled. Could she be his wife? Surely not. His daughter? "Ah, this young lady, sir."

The man gave him a brief bow in return. "I know who you are. As for the young lady, she has already promised this waltz to my son."

Nicholas flashed a quick look at a young man around his own age, smiling at something the girl said to him. He looked up, cocked his head to one side, and nodded to Nicholas. Then the girl turned to look at him, straight on, her eyes never leaving his face. So joyous she'd been, but now her expression was remote and unreadable. But he saw something in her eyes, something—knowledge, secrets, he didn't know. Ah, but he would, and soon. Then the young man spoke to her and she placed her hand on his forearm and let him lead her to the dance floor. She did not look back at him.