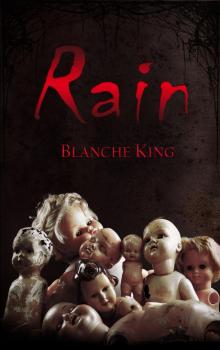

Rain

Blanche King

RAIN

Above the splattering rain and noise, the crowd shouted insults to their heart’s content. Like the execution of King Charles, a procession of black marched towards the gallows, minus a monarch, plus the thick fog of London. It was justice in progress. Shackles clanked, clunked.

The man in front had a grin so wide his eyes squinted into crescent moons. He stood a scarecrow: tall, perhaps once handsome, covered in bruises. Water dripped from his patchwork rags, once grey, now black from the moisture and flying soot. Behind him followed two priests, hands folded, chanting with their eyes rolled towards the sky. Then came the three magistrates, four guards, a red-headed woman, and a dozen angry villagers.

A magistrate coughed. The crowd fell silent.

“For the murders of Dr. Henry Baugh, Mr. Scott Estel, and our beloved Mayor and philanthropist, Sir Harold Foxworth, you are hereby sentenced to death.”

“Please George,” said the red-haired woman.

“May God have mercy on your soul,” said both priests at once.

The man continued to grin.

Two guards grabbed his arms and pushed him towards the noose.

“Any last words?” said the magistrates.

“Please George,” said the woman.

The man glanced at her, then at everyone else. The crowd shrank back as his gaze swept over them. “Shoot me,” said the man. The magistrates exchanged glances.

“Shoot me,” he said. “But do it with a smile.”

Thunder roared. A flash of lightning hit the gallows. One of the guards panicked. A gun went off. Bam! The crowd fell silent.

When the air cleared, a shaking guard stood splattered in blood, holding a smoking pistol. On the ground laid the grinning man, dead, but still grinning. The red-headed woman buried her head in her hands.

“Please George,” she said. “Stop smiling.”

…..

March brought with it splattering rain. Five children sat under a bridge to avoid the downpour. The river flooded, rushing towards the sewers with everyone and everything. A handkerchief, a top hat, someone’s cat, meowing as it dropped behind the gutter bars.

The little red-haired girl held out her hand. “This is paper, and if you make a sideways peace sign, it’s ‘scissors’. Scissors beats paper, but rock beats scissors.” She balled her hand into a fist. “This is rock. It loses to paper, okay?”

The two ash-blond kids nodded: a pretty girl with pigtails and a chubby boy. Height-wise, they were smaller, but all three wore rags too big for their persons.

The boy looked at his palm. “Can I be ‘paper’, Riley? I like the paper sign.”

The blond girl swatted him on the shoulder. “You’re not supposed to tell her, you dummy,” she said. “The point of the game is to pull a fast one over your enemies and beat’em.”

“But I don’t want to pull a fast one,” said the boy. “I want Riley to win.”

The other girl groaned.

“It’s okay, Suzy,” said the boy. “You can win too. I—”

Suzy smacked him on the head. “You’re stupid,” she said. “I don’t want to play anymore.” She got up and moved next to the other two kids. The boy with the news cap latched onto her arm. The other, the freckled one, went on whistling.

“Wonder when Old Man Foxworth is coming,” said the news-capped boy. “He found Isaac a home last week. It oughta be my turn this time, right Ed?”

“Keep dreaming, Jimmy” said freckles. “It’s gonna be me this week. He’s been taking us by age, member? Isaac was ten. He’s gots a whole year on me.”

The other boy counted his fingers. “But that means I don’t get to go until Suzy’s gone. It’s gonna be you, then Suzy, then me, then Riley, and then George cause he’s only seven.”

“Seven and a half,” said the chubby boy. He jumped to his feet and kicked the other boy in the shins. “And I’m bigger than you.”

“No you ain’t,” said Suzy. “You’re just fatter than him.”

While the others laughed, George ran and huddled by Riley. “They’re so mean,” he said. “I miss my mommy.”

Riley patted his head. “She’s in a better place with all of our mommies,” she said. “It’s okay. Smile, Georgy. Everything will be better when we get new families.”

“Yeah,” said Edmund. “We’ll be warm again, and fed, and I’m gonna get myself a cricket bat…” He made a swinging gesture, as if clutching the equipment.

“I want a new dress,” said Suzy.

“And a whole roasted chicken,” said Riley.

“And stockings full of marshmallows.”

“Yeah, marshmallows.” Edmund stared into the rain. “Wish old man Foxworth would come already. Probably caught in the storm. Wish there was no rain.”

“It’s okay, Ed,” said Riley. “I’m sure he’ll come tomo…” She suddenly inhaled. Her hand shot out, pointing into the distance. “Look.”

A silhouette appeared through the fog, growing bigger and more defined as it got closer. Footsteps sloshed against the liquid soil. Before the children stood a well-dressed gentleman in his late forties, carrying an umbrella, with his graying hair tucked under a tall hat. His shoes shined beneath a coat of mud.

“Hello children,” said Mr. Foxworth. “Have we been good this week?”

The five kids nodded. Suzy hugged the old man’s waist.

“You came,” she said. “We thought you wouldn’t come because of the rain.”

Mr. Foxworth patted her head. “Don’t be silly. Nothing could keep me from you children.” He reached into his pocket and handed each of them a piece of candy. “There, there,” he said. He pulled out a silver chain with the letter “E” and handed it to Edmund. “For you, so the others will recognize you someday when you meet again. Are we ready to leave, Edmund?”

Edmund nodded.

The other children waved as their friend followed Mr. Foxworth down the road and into a carriage. “It’s my turn next week,” said Suzy. “I hope I get a family who likes little girls.”

The rain stopped next morning, and did not continue until the week after.

“I swear God’s playing a trick on us,” said Jimmy. “Why does it only rain when Mr. Foxworth’s coming?”

“Maybe he’ll still come.” Suzy sat by the edge of the bridge, staring into the distance. “He came when it was Edmund’s turn. Maybe…”

And then they saw him. Out of the fog appeared Mr. Foxworth, with an umbrella in hand and a tall hat on his head.

“Here you go, your weekly sweets,” he said, giving each child a piece of candy and Suzy a silver “S.” “I found a nice doctor to take in Suzy. He likes children a great deal, and he’s anxious to meet his new little girl.”

Suzy cheered. Riley thanked him. George coughed.

He kept coughing. Riley patted him on the back.

“What’s wrong with him?” said Mr. Foxworth.

“He’s always sick,” said Jimmy. “Something’s wrong with his heart. We don’t got no medicine, so we just give him water and hope he gets better. Riley looks after him.”

Mr. Foxworth studied George for a minute. Riley looked from him to George. “Maybe you could make an exception this time, Mr. Foxworth, and take Suzy next week? George really needs a doctor.”

“No!” Suzy jumped to her feet. “It’s my turn. I want a new home. I want my new daddy.”

“You can go next time,” said Riley. “George is getting worse each week.”

Suzy burst into tears and buried her face in Mr. Foxworth’s coat. “Please take me,” she said. “I want a family so much.”

“There, there,” said Mr. Foxworth. “I’m afraid Suzy has a point. I already promised the doctor a young girl, and I’d hate to break her heart over a week’s wait.” He pushed Suzy towa

rds the carriage. “Come along, little one.”

As the three watched Suzy disappeared, Jimmy leaned back against the bridge and crossed his arms. “Guess I’m next,” he said. “Wonder who I’m gonna get.”

“Couldn’t you let George go before you?” said Riley.

Jimmy turned away. Riley put her hand on his shoulder.

“Please?” she said. “For a friend?”

“No!” Jimmy sprung up and pushed her away. “You don’t get it do you? We’re only friends because we all got nowhere to go. But now I do, and I’m gonna go, even if I never see any of you again.”

Tears welled up in Riley’s eyes. Jimmy bit his lip. “I’d give anything to be in a family, Riley. Anything… and don’t tell me you wouldn’t either.”

Riley turned away, swiping at her face.

“Don’t cry, Riley,” said George. “I can wait.” He turned his head sideways and smiled. “We’ll be okay,” he said. “Do you want to play a game?”

“Okay,” said Riley. “Thanks Georgy. And thank you for smiling.”

“It’s like you said, Riley. When everything seems grey, the least we can do is to remember to smile.”

The next week, Mr. Foxworth appeared through the fog and took Jimmy. The rain poured harder than ever.

“How are Ed and Suzy?” said Riley. “Are they better?”

“Naturally,” said Mr. Foxworth. “You would hardly recognize them.”

He took Jimmy and left. Later that week, the rain relented. Riley and George sat on top of a tavern roof, watching the city.

“I wonder if we’ll ever see Jimmy again,” said Riley. “I hope that the sweet shop owner will be good to him.”

“I’m sure he