A Jay of Italy

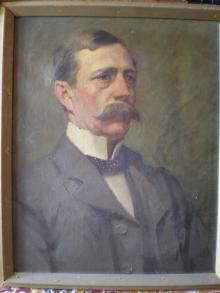

Bernard Edward Joseph Capes

Produced by Al Haines.

A JAY OF ITALY

BY

BERNARD CAPES

'...Some Jay of Italy,Whose mother was her painting, hath betrayed him.' CYMBELINE

FOURTH EDITION

METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET W.C. LONDON

First Published . . July 1905 Second Edition . . August 1905 Third Edition . . September 1905 Fourth Edition . . October 1905

*A JAY OF ITALY*

*CHAPTER I*

On a hot morning, in the year 1476 of poignant memory, there drew upbefore an osteria on the Milan road a fair cavalcade of travellers.These were Messer Carlo Lanti and his inamorata, together with a suiteof tentmen, pages, falconers, bed-carriers, and other personnel of amigratory lord on his way from the cooling hills to the Indian summer ofthe plains. The chief of the little party, halting in advance of hisfellows, lifted his plumed scarlet biretta with one strong young hand,and with the other, his reins hanging loose, ran a cluster of swarthyfingers through his black hair.

'O little host!' he boomed, blaspheming--for all good Catholics,conscious of their exclusive caste, swore by God prescriptively--'Olittle host, by the thirst of Christ's passion, wine!'

'He will bring you hyssop--by the token, he will,' murmured the lady,who sat her white palfrey languidly beside him. She was a slumberous,ivory-faced creature warm and insolent and lazy; and the little bells ofher bridle tinkled sleepily, as her horse pawed, gently rocking her.

The cavalier grunted ferociously. 'Let me see him!' and, bonnetinghimself again, sat with right arm akimbo, glaring for a response to hiscry. He looked on first acquaintance a bully and profligate--which hewas; but, for his times, with some redeeming features. His thigh, inits close violet hose, and the long blade which hung at it seemedsomehow in a common accord of steel and muscle. His jaw was underhung,his brows were very thick and black, but the eyes beneath weregood-humored, and he had a great dimple in his cheek.

A murmur of voices came from the inn, but no answer whatever to thedemand. The building, glaring white as a rock rolled into the plainsfrom the great mountains to the north, had a little bush of juniperthrust out on a staff above its door. It looked like a dry tongueprotruded in derision, and awoke the demon in Messer Lanti. He turnedto a Page:--'Ercole!' he roared, pointing; 'set a light there, and givethese hinds a lesson!'

The lady laughed, and, stirring a little, watched the page curiously.But the boy had scarcely reached the ground when the landlord appearedbowing at the door. The cavalier fumed.

'Ciacco--hog!' he thundered: 'did you not hear us call?'

'Illustrious, no.'

'Where were your ears? Nailed to the pillory?'

'Nay, Magnificent, but to the utterances of the little Parablist of SanZeno.'

'O hog! now by the Mass, I say, they had been better pricked to thybusiness. O ciacco, I tell thee thy Parablist was like, in anothermoment, to have addressed thee out of a burning bush. What! I woulddrink, swine! And, harkee, somewhere from those deep vats of thine theperfume of an old wine of Cana rises to my nostrils. I say no more.Despatch!'

The landlord, abasing himself outwardly, took solace of a private curseas he turned into the shadow of his porch--

'These skipjacks of the Sforzas! limbs of a country churl!'

Something lithe and gripping sprang upon his back as he muttered, makinghim roar out; and the chirrup of a great cricket shrilled in his ear--

'Biting limbs! clawing, hooking, scoring limbs! ha-ha, hee-hee,ho-bir-r-r-r!'

Boniface, sweating with panic, wriggled to shake off his incubus. Itclung to him toe and claw. Slewing his gross head, he saw, squattedupon his shoulders, a manikin in green livery, a monstrous grasshopperin seeming.

'Messer Fool,' he gurgled--'dear my lord's most honoured jester!' (hewas essaying all the time to stagger with his burden out ofearshot)--'prithee spare to damn a poor fellow for a hasty word underprovocation! Prithee, sweet Messer Fool!'

The little creature, sitting him as a frog a pike, hooked its smalltalons into the corners of his eyes.

'Provocation!' it laughed, rocking--'provocation by his grandness to aguts! If I fail to baste thee on a spit for it, call me not Cicada!'

'Mercy!' implored the landlord, staggering and groping.

'Nothing for nothing. At what price, tunbelly?'

The landlord clutched in his blindness at the post of a descendingstair.

'The best in my house.'

'What best, paunch?'

'Milan cheese--boiled bacon. Ah, dear Messer Cicada, there is a fatcold capon, for which I will go fasting to thee.'

'And what wine, beast?'

'What thou wilt, indeed.'

The jester spurred him with a vicious heel.

'Away, then! Sink, submerge, titubate, and evanish into thy crystalvaults!'

'Alas, I cannot see!'

The rider shifted his clutch to the fat jowls of his victim, whothereupon, with a groan, descended a rude flight of steps at a run, andbrought up with his burden in a cool grotto. Here were casks andstoppered jars innumerable; shelves of deep blue flasks; lollingamphorae, and festoons of cobwebs drunk with must. Cicada leapt with onespring to a barrel, on which he squatted, rather now like a green frogthan a grasshopper. His face, lean and leathery, looked as if dipped ina tan-pit; his eyes were as aspish as his tongue; he was a stunted,grotesque little creature, all vice and whipcord.

'Despatch!' he shrilled. 'Thy wit is less a desert than my throat.'

'Anon!' mumbled the landlord, and hurried for a flask. 'Let thy tongueroll on that,' he said, 'and call me grateful. As to the capon,prithee, for my bones' sake, let me serve thy masters first.'

The jester had already the flask at his mouth. The wine sank into himas into hot sand.

'Go,' he said, stopping a moment, and bubbling--'go, and damn thy capon;I ask no grosser aliment than this.'

The landlord, bustling in a restored confidence, filled a great bottlefrom a remote jar, and armed with it and some vessels of twisted glass,mounted to daylight once more. Messer Lanti, scowling in the sun,cursed him for a laggard.

'Magnificent!' pleaded the man, 'the sweetest wine, like the sweetestmeat, is near the bone.'

'Deep in the ribs of the cellars, meanest, O, ciacco?'

He took a long draught, and turned to his lady.

'Trust the rogue, Beatrice; it is, indeed, near the marrow ofdeliciousness.'

She sipped of her glass delicately, and nodded. The cavalier held outhis for more.

'Malvasia, hog?'

'Malvasia, most honoured; trod out by the white feet of prettiestcontadina, and much favoured, by the token, of the Abbot of San Zenoyonder.'

Messer Lanti looked up with a new good-humour. The party was halted in agreat flat basin among hills, on one of the lowest of which, remote andaustere, sparkled the high, white towers of a monastery.

'There,' he said, signifying the spot to his companion with a grin;'hast heard of Giuseppe della Grande, Beatrice, the _father_ of hispeople?'

'And not least of our own little Parablist, Madonna,' put in thelandlord, with a salutation.

'Plague, man!' cried Lanti; 'who the devil is this Parablist you keepthrowing at us?'

'They call him Bernardo Bembo, my lord. He was dropped and bred amongthe monks--some by-blow of a star, they say, in the year of the greatfall. He was found at the feet of Mary's statue; and, certes, he isgifted like an angel. He

mouths parables as it were prick-songs, and isesteemed among all for a saint.'

'A fair saint, i'faith, to be carousing in a tavern.'

'O my lord! he but lies here an hour from the sun, on his way, this verymorning, to Milan, whither he vouches he has had a call. And for hiscarousing, spring water is it all, and the saints to pay, as I know tomy cost.'

'He should have stopped at the rill, methinks.'

'He will stop at nothing,' protested the landlord humbly; 'nay, not eventhe rebuking by his parables of our most illustrious lord, the DukeGaleazzo himself.'

Lanti guffawed.

'Thou talkest treason, dog. What is to rebuke there?'

'What indeed, Magnificent? Set a saint, _I_ say, to catch a saint.'

The other laughed louder.

'The right sort of saint for that, I trow, from Giuseppe's loins.'

'Nay, good my lord, the Lord Abbot himself is no less a saint.'

'What!' roared Lanti, 'saints all around! This is the right hagiolatry,where I need never despair of a niche for myself. I too am the son ofmy father, dear Messer Ciacco, as this Parablist is, I'll protest, ofyour Abbot, whose piety is an old story. What! you don't recognise afamily likeness?'

The landlord abased himself between deference and roguery.

'It is not for me to say, Magnificent. I am no expert to prove thecommon authorship of this picture and the other.'

He lowered his eyes with a demure leer. Honest Lanti, bending to rallyhim, chuckled loudly, and then, rising, brought his whip with aboisterous smack across his shoulders. The landlord jumped and winced.

'Spoken like a discreet son of the Church!' cried the cavalier.

He breathed out his chest, drained his glass, still laughing into it,and, handing it down, settled himself in his saddle.

'And so,' he said, 'this saintly whelp of a saint is on his way torebuke the lord of Sforza?'

'With deference, my lord, like a younger Nathan. So he hath beenmiscalled--I speak nothing from myself. The young man hath lived all hisdays among visions and voices; and at the last, it seems, they'vespelled him out Galeazzo--though what the devil the need is there? asyour Magnificence says. But perhaps they made a mistake in thespelling. The blessed Fathers themselves teach us that the bestholiness lacks education.'

Madonna laughed out a little. 'This is a very good fool!' she murmured,and yawned.

'I don't know about that,' said Lanti, answering the landlord, andwagging his sage head. 'I'm not the most pious of men myself. But tellus, sirrah, how travels his innocence?'

'On foot, my lord, like a prophet's.'

''Twill the sooner lie prone.' He turned to my lady. 'Wouldst like toadd him to Cicada and thy monkey, and carry him along with us?'

'Nay,' she said pettishly, 'I have enough of monstrosities. Will youkeep me in the sun all day?'

'Well,' said Lanti, gathering his reins, 'it puzzles me only how theAbbot could part thus with his discretion.'

'Nay, Illustrious,' answered the landlord, 'he was in a grievous pet,'tis stated. But, there! prophecy will no more be denied than love. A'must out or kill. And so he had to let Messer Bembo go his gaits with aletter only to this monastery and that, in providence of a sanctuary,and one even, 'tis whispered, to the good Duchess Bona herself. Buthere, by the token, he comes.'

He bowed deferentially, backing apart. Messer Lanti stared, and gave aprofound whistle.

'O, indeed!' he muttered, showing his strong teeth, 'this Giuseppepropagates the faith very prettily!'

Madam Beatrice was staring too. She expressed no further impatience tobe gone for the moment. A young man, followed by some kitchen companyadoring and obsequious, had come out by the door, and stood regardingher quietly. She had expected some apparition of austerity, some lean,neurotic friar, wasting between dogmatism and sensuality. And insteadshe saw an angel of the breed that wrestled with Jacob.

He was so much a child in appearance, with such an aspect of wonder andprettiness, that the first motion of her heart towards him was like theleap of motherhood. Then she laughed, with a little dye come to hercheek, and eyed him over the screen of feathers she held in her hand.

He advanced into the sunlight.

'Greeting, sweet Madonna,' he said, in his grave young voice, 'and fairas your face be your way!' and he was offering to pass her.

She could only stare, the bold jade, at a loss for an answer. The softumber eyes of the youth looked into hers. They were round and velvetyas a rabbit's, with high, clean-pencilled brows over. His nose wasshort and pretty broad at the bridge, and his mouth was a little mouth,pouting as a child's, something combative, and with lips like tintedwax. Like a girl's his jaw was round and beardless, and his hair agolden fleece, cut square at the neck, and its ends brittle as if theyhad been singed in fire. His doublet and hose were of palest pink; hisbonnet, shoes, and mantlet of cypress-green velvet. Rose-colouredribbons, knotted into silver buckles, adorned his feet; and over hisshoulder, pendent from a strand of the same hue, was slung a fair lute.He could not have passed, by his looks, his sixteenth summer.

Lanti pushed rudely forward.

'A moment, saint troubadour, a moment!' he cried. 'It will please us,hearing of your mission, to have a taste of your quality.'

The youth, looking at him a little, swung his lute forward and smiled.

'What would you have, gracious sir?' he said.

'What? Why, prophesy us our case in parable.'

'I know not your name nor calling.'

'A pretty prophet, forsooth. But I will enlighten thee. I am CarloLanti, gentleman of the Duke, and this fair lady the wife of him we callthe Count of Casa Caprona.'

The boy frowned a little, then nodded and touched the strings. And allin a moment he was improvising the strangest ditty, a sort of cantefablebetween prose and song:--

'A lord of little else possessed a jewel, Of his small state incomparably the crown. But he, going on a journey once, To his wife committed it, saying, "This trust with you I pledge till my return; See, by your love, that I redeem my trust." But she, when he was gone, thinking "he will not know," Procured its exact fellow in green glass, And sold her lord's gem to one who bid her fair; Then, conscience-haunted, wasted all those gains Secretly, without enjoyment, lest he should hear and wonder. But he returning, she gave him the bauble, And, deceived, he commended her; and, shortly after, dying, Left her that precious jewel for all dower, Bequeathing elsewhere the residue of his estate. Now, was not this lady very well served, Inheriting the whole value, as she had appraised it, Of her lord's dearest possession? Gentles, Dishonour is a poor estate.'

Half-chaunting, half-talking, to an accompaniment of soft-touchedchords, he ended with a little shrug of abandonment, and dropped thelute from his fingers. His voice had been small and low, but pure; thesweet thrum of the strings had lifted it to rhapsody. Messer Lantiscratched his head.

'Well, if that is a parable!' he puzzled. 'But supposing it aims at ourcase, why--Casa Caprona is neither poor nor dead; and as to a jewel----'

He looked at Madam Beatrice, who was frowning and biting her lip.

'Why heed the peevish stuff?' she said. 'Will you come? I am sick tobe moving.'

Carlo was suddenly illuminated.

'O, to be sure, of course!' he ejaculated--'the jewel----'

'Hold your tongue!' cried the lady sharply.

The honest blockhead went into a roar of laughter.

'He has touched thee, he has touched thee! And these are his means toconvert the Duke! By Saint Ambrose, 'twill be a game to watch! I swearhe shall go with us.'

'Not with my consent,' cried madam.

Carlo, chuckling tormentingly, looked at her, then doffed his capmockingly to the boy.

'Sweet Messer Bembo,' he said, 'I take your lesson much to heart, andpray you gratefully--as we are both for Milan, I understand--to give usthe honour of your company thither. I am in good standi

ng with theDuke, I say, and you would lose nothing by having a friend at court.Those half-boots'--he glanced at the pretty pumps--'could as ill affordthe penalties of the road as your innocence its dangers.'

'I have no more fear than my divine Master,' said the boy boldly, 'incarrying His gospel of love.'

'Well for you,' said Carlo, with a grin of approval for his spirit; 'buta gospel that goes in silken doublet and lovelocks is like to be struckdumb before it is uttered.'

'As to my condition, sir,' said the boy, 'I dress as for a feast, ourMaster having prepared the board. Are we not redeemed and invited? Wewalk in joy since the Resurrection, and Limbo is emptied of its gloom.The kingdom of man shall be love, and the government thereof. Preachheresy in rags. 'Twas the Lord Abbot equipped me thus, my own stoutheart prevailing. "Well, they will encounter an angel walking by theroad," quoth he, "and, if they doubt, show 'em thy white shoulder-knobs,little Bernardino, and they will see the wings sprouting underneath likethe teeth in a baby's gums."'

He was evidently, if sage or lunatic, an amazing child. The roughlibertine was quite captivated by him.

'Well, you will come with us, Bernardino?' said he; 'for with a crackedskull it might go hard with you to prove your shoulder-blades.'

'I will come, lord, to reap the harvest where I have sowed the grain.'

He looked with a serene severity at the countess.

'Shalt take thee pillion, Beatrice,' shouted Lanti. 'Up, prettytroubadour, and recount her more parables by the way.'

'May I die but he shall not,' cried the girl.

'He shall, I say.'

'I will bite, and rake him with my nails.'

'The more fool you, to spoil a saint! Reproofs come not often in such aguise as this. Up, Bernardino, and parable her into submission!'

She made a show of resisting, in the midst of which Bembo won to hisplace deftly on the fore-saddle. At the moment of his success, the foolCicada sprang from the tavern door, and, lurching with wild, glazedeyes, leapt, hooting, upon the crupper of the beast, almost bringing itupon its haunches. With an oath Lanti brought down his whip with suchfury that the fool rolled in the dust.

'Drunken dog!' he roared, and would have ridden over the writhing body,had not Bembo backed the white palfrey to prevent him.

'Thou strik'st the livery, not the man!' he cried. 'Hast never thyselfbeen drunk, and without the excuse of this poor fool to make a trade offolly?'

Messer Lanti glared, then in a moment laughed. The battered grasshoppertook advantage of the diversion to rise and slink to the rear. The nextmoment the whole cavalcade was in motion.