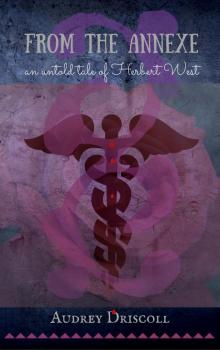

From the Annexe: An Untold Tale

Audrey Driscoll

A Herbert West Series Supplement

FROM THE ANNEXE

An Untold Tale

by

Audrey Driscoll

Copyright 2016 by Audrey Driscoll

ISBN 978-0-9949432-7-9

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, brands, media and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

*******

Cover art by Audrey Driscoll, using Canva

Aldus leaf Unicode 2766 image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

FROM THE ANNEXE

an untold tale

This is how it could have been. Yes, and in a way it was. In the empty years, but before I lost the secret glory, I dreamed and imagined just how it might have been if I had realized certain things a little earlier, if certain events had taken place a little sooner…

I created this for myself, from memories and hopes, and longings I discovered after it was too late. I knew it was self-indulgent, foolish, even pathetic. But I did it anyway, because I had to.

Because I knew him so well, though, and myself also, I made it a not altogether happy tale. Long ago, I learned that even the wildest creations of the imagination must have a link to reality. Without this, they refuse to come to life, like corpses that have lain too long in death. And even the wildest creations of the imagination must be rooted in the heart. This is the most resonant of links. So although I gave him to myself as a gift, it was he as he was, not as I wished him to be.

This is my account of something beyond friendship that grew between myself and Herbert West, physician and necromancer. It began, or did not, but could have, in the winter of 1920, when, to his distress, he found, and then lost, his mother…

He stood up and began to pace again. I said nothing, knowing this was his habit when he had something on his mind. Suddenly, he stopped in front of me and said, "All my life, I've known exactly what I am, even when I've not been entirely happy about it. You could say I made myself, more than most people do. When I met obstacles, such as my father and my brothers, or the rules of the Medical School, or the rules of death for that matter, I always managed to find a way around or over or through them. But this – I don't think I can get around it, or away from it. This might destroy me. I can feel a change already."

"I don't understand. What sort of change?"

"Insanity, Charles. It's in my blood. It must be. She was my mother; there is no doubt about that. You heard her raving, there in the lab. And don't forget my father's legacy. I'm the son of a murderer and a madwoman. You know the results of the first. Now this other thing, just when I could see my way clear." He covered his face with his hands.

This was the man who had once said to me, "Nothing can shock me any more." Well, now something had. I did not know what to do, so I laid a hand on his shoulder, feeling awkward.

"Herbert," I said, "surely it isn't so black as you imagine. Don't forget, I'm the son of a suicide. And yet, I don't think it has affected me in any lasting way. I don't expect to be driven to do what he did."

"That's not the same." He turned and looked at me with an expression of despair. "Suicide could actually be seen as a rational choice, in some situations. And your father, from what you tell me, was a perfectly ordinary, competent individual until his bank failed. This is… insidious. And inescapable."

"But nothing about you has changed since you made this discovery," I persisted. "You're the same person as you were before."

"The person I was before was living in a state of blessed ignorance. Then I saw a clear road before me. Now it's full of hidden pits."

He looked so wretched I felt I had to do something to comfort him. I could think of nothing more to say, so I put my arms around him. Handshakes aside, and except for the time Kid O'Brien had nearly choked him to death, this was my first physical contact with him in the nine years of our friendship. He began to pull away, but then relaxed and leaned against me, laying his head on my shoulder like a tired child. I felt the length of his slight body against mine. I smelled the narcissus perfume of the stuff he used on his hair. The moment spun out as if to eternity, and then ended. He drew away from me with a sigh.

"You're a good friend to me, Charles," he said. "Better than I deserve, perhaps. It's been a difficult day. I had better go. Good night."

After you left, I sat for a long while, staring into the dying embers of the fire and thinking. I had already begun to suspect something about you. The thing that made me almost certain happened at one of the dinner parties you held for your professional colleagues. Looking back, I'm surprised it didn't at the same time reveal me to myself. I felt lucky only to be your friend, and so did not realize that James Williams and I had something in common.

I can see it again, vividly – all of us gathered in your parlour, Billington playing the piano, you and Nicholson singing some duet with such enthusiasm that when you finished we all cheered and applauded. Except Williams, who was gazing at you with a fixed and hungry stare with only one possible meaning – even to me, naïve as I was. And then the look you gave him – I expected the man to fall dead on the spot, from the sheer icy intensity of it.

What did any of this have to do with me? Nothing, then. So what if I suspected – no, knew – that you were attracted to men rather than women? I was not so naïve as to be unaware of this phenomenon. I had read my Plato. I knew what sort of love was discussed in Phaedrus.

I thought of the many times I had observed you during our experiments, while we waited for signs of returning life. I watched your face, self-absorbed or animated, your moods like changeable weather reflected in your eyes. I told myself I was observing you for the sake of gathering knowledge about one who was to me remarkable. I was like a scientist watching the growth and flowering of a rare orchid he has been privileged to discover. But I realize now it was something far less scientific that motivated me, even then.

For weeks I was alone with my secret. At length, I began to doubt. Surely this could not be. It was Alma I felt this way about, not him. She's been away too long, I thought. No one else can substitute for her. I've tried to find that person, these five years since she left, without success. What had I been looking for? In truth, I had to admit that no vivacious, blue-eyed blonde had measured up to some elusive image of perfection. I had assumed that image was Alma's. But now I saw how wrong I had been.

After his mother's funeral service, I invited him to share a meal with me and return to my rooms afterward. He seemed lost, and I did not want him to be alone. In his eyes I could see the orphan he had become.

Finally, he began to talk. He spoke of the things his mother had revealed, troubling as they were. Of the reasons for her disappearance when he was a child, the pathetic brevity of her self-chosen life of freedom before the dark waters of madness engulfed her. And always, of the possibility (although in his mind it was a certainty) that he himself was infected with her madness.

I did what I could. I reminded him of his work, his love of it, his fitness for it. I advised him to forget about his parents' troubles and to live as he had lived before. If madness was indeed his fate, I said, it would claim him soon enough, whether he worried about it or not.

"In that case," he said, "the kindest thing you could do would be to shoot me. The very thought of becoming one of those dribbling idiots at Sefton

fills me with horror. But thank you, Doctor Milburn, for your advice. I shall surely consider it. There is a practicality about it that appeals to me. And now I should go home."

But he was not ready to leave. Twice, he started for the door, and both times came back. He seemed agitated again, but not, I thought, for the same reasons as before. All at once, he said, "At a time like this, I wish we were… It would be good to have someone who…"

He came closer to me. "Charles," he said, "I don't know what you might think of desires that are… abnormal."

I had no idea at first what he was talking about, but that word, 'abnormal,' told me he had not let go of his obsession with what he thought of as his