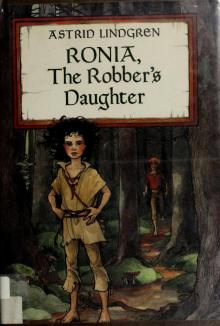

Ronia, The Robber's Daughter

Astrid Lindgren

OTHER BOOKS BY ASTRID LINDGREN

Pippi Longstocking

Pippi Goes on Board

Pippi in the South Seas

Pippi on the Bun

The Brothers Lionheart

The Children of Noisy Village

Christmas in Noisy Village

First American Edition

Translation Copyright © 1983 by Viking Penguin Inc.

All rights reserved

Originally published in 1981 as RONJA RÖVARDOTTER by Rabén & Sjögren Bokforlag, Stockholm. Copyright © 1981 by Astrid Lindgren.

Published in 1983 by The Viking Press

40 West 23rd Street, New York, N. Y. 10010 Published simultaneously in Canada by Penguin Books Canada Limited Printed in U. S. A.

1 2 3 4 5 87 86 85 84 83

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Lindgren, Astrid, date Ronia, the robber’s daughter.

Translation of: Ronja rövardotter.

Summary: Ronia, who lives with her father and his band of robbers in a castle in the woods, causes trouble when she befriends the son of a rival robber chieftain.

1. Robbers and outlaws—Fiction I. Title.

TPZ7. L6585Ro 1983 [Fie] 82-60081 ISBN 0-670-60640-5

One

On the night that ronia was born a thunderstorm was raging over the mountains, such a storm that all the goblinfolk in Matt’s Forest crept back in terror to their holes and hiding places. Only the fierce harpies preferred stormy weather to any other and flew, shrieking and hooting, around the robbers’ stronghold on Matt’s mountain. Their noise disturbed Lovis, who was lying within, preparing to give birth, and she said to Matt, “Drive the hell-harpies away and let me have some quiet. Otherwise I can’t hear what I’m singing!”

The fact was that Lovis liked to sing while she was having her baby. It made things easier, she insisted, and the baby would probably be all the jollier if it arrived on earth to the sound of a song.

Matt took his crossbow and shot off a few arrows through one of the arrow slits of the fort. “Be off with you, harpies!” he shouted. “I’m going to have a baby tonight—get that into your heads, you hags!”

“Ho, ho, he’s going to have a baby tonight,” hooted the harpies. “A thunder-and-lightning baby, small and ugly it’ll be, ho, ho!”

Then Matt shot again, straight into the flock, but they simply jeered at him and flew off across the treetops, hooting angrily.

While Lovis lay there, giving birth and singing, and while Matt quelled the wild harpies as best he could, his robbers were sitting by the fire down in the great stone hall, eating and drinking and behaving as rowdily as the harpies themselves. After all, they had to do something while they waited, and all twelve of them were waiting for what was about to happen up there in the tower room. No child had ever been born in Matt’s Fort in all their robber days there.

Noddle-Pete was waiting most of all.

“That robber baby had better come soon,” he said. “I’m old and rickety, and my robbing days will soon be over. It would be fine to see a new robber chief here before I’m finished.”

He had scarcely stopped speaking when the door opened and Matt rushed in, quite witless with delight. He raced all the way around the hall, leaping high with joy and shrieking like a madman.

“I’ve got a child! Do you hear me—I’ve got a child!”

“What sort of child is it?” asked Noddle-Pete over in his corner.

“A robber’s daughter, joy and gladness!” shouted Matt. “A robber’s daughter—here she comes!”

And over the high threshold stepped Lovis with her baby in her arms. All the robbers’ noise turned off at once.

“I do believe that’s made your beer go down the wrong way, ” said Matt. He took the baby girl from Lovis and carried her around among the robbers.

“Here! Want to see the most beautiful child ever born in a robbers’ fort? “

His daughter lay there in his arms, looking up at him with wide, bright eyes.

“That child understands just about everything already—you can see that, ” said Matt.

“What will you call her? ” asked Noddle-Pete.

“Ronia, ” said Lovis. “I decided that a long time ago. “

“What if it had been a boy? ” said Noddle-Pete.

Lovis gave him a calm, stern look. “If I decide my baby is to be called Ronia, it will be a Ronia! “

Then she turned to Matt. “Shall I take her now? “

But Matt did not want to hand over his daughter. He stood there gazing in admiration at her clear eyes, her little mouth, her black tufts of hair, her helpless hands, and he trembled with love.

“You, baby, you’re already holding my robber heart in those little hands, ” he said. “I don’t understand it, but that’s how it is. “

“Could I hold her for a bit? ” Noddle-Pete asked, and Matt laid Ronia in his arms as if she were a golden egg.

“I give you the new robber chieftain you’ve been talking about all this time. Don’t drop her, whatever you do, or it will be your last hour! “

But Noddle-Pete just smiled his toothless smile at Ronia. “There’s no real weight to her,” he said, surprised, raising and lowering her a couple of times.

That made Matt angry, and he snatched his baby back. “What did you expect, numskull? A great fat robber chieftain with a bulging belly and a pointed beard, eh?”

All the robbers realized then that there must be no comments about this child if they wanted to keep Matt in a good mood. And it really was not wise to annoy him. So they set to work at once, praising and extolling the newborn baby. They also emptied a great many tankards of beer in her honor, which made Matt happy. He threw himself down on his high seat among them and showed off his remarkable child again and again.

“This is going to plague the life out of Borka,” said Matt. “He can sit there in his miserable robbers’ den and gnash his teeth with jealousy. Yes, death and destruction! There will be such a gnashing that all the wild harpies and gray dwarfs in Borka’s Wood will hold their ears, believe me!”

Noddle-Pete nodded gleefully and said with a little snigger, “Sure enough, it will plague the life out of Borka. Now Matt’s line will live on, but Borka’s line will be finished and done for.”

“Yes,” said Matt, “finished and done for, sure as death! As far as I know, Borka has not managed to get a child, and is not likely to either.”

Then came a crack of thunder the like of which had never been heard in Matt’s Wood before. It made even the robbers turn pale, and Noddle-Pete fell flat on his back, weak as he was. A piteous little cry came unexpectedly from Ronia, and that shook Matt worse than the thunderclap.

“My child’s crying!” he shrieked. “What do we do, what do we do?”

But Lovis was standing by calmly. She took the baby from him and put her to her breast, and there was no more crying.

“That was a good crack,” said Noddle-Pete, when he too had calmed down a little. “I’ll take my dying oath it struck.”

Yes, the lightning had struck and in earnest, too, as they saw when morning came. The ancient fortress high up on Matt’s Mountain had been cleft down the middle. From the highest battlements to the deepest vault of the dungeons, the fortress was now split in two halves, with a chasm between them.

“Ronia, your young life has gotten off to a grand start,” said Lovis, as she stood by the shattered wall with the baby in her arms, looking at the disaster.

Matt was raging like a wild animal. How could this have been allowed to happen to his forefathers’ old fortress? But Matt could not go on being angry about anything for long, and he could always find reasons to take comfort.

&nbs

p; “Oh, well, we shan’t have so many twists and turns and cellar pits and rubbish to keep track of. And perhaps no one will need to get lost in Matt’s Fort any more. Remember what it was like when Noddle-Pete went astray and didn’t turn up for four days!”

Noddle-Pete did not enjoy being reminded of this occasion. Was it his fault he had gotten lost? He had only been trying to find out how vast and rambling Matt’s Fort really was, and had indeed found it big enough to get lost in. Poor thing, he was almost half dead before he finally found his way back to the great stone hall. Thank goodness the robbers had been bawling and kicking up enough noise for him to hear them a long way off; otherwise he would never have gotten back.

“In any case, we have never used the whole fort,” said Matt, “and we will go on living in our hall and bedrooms and tower rooms where we have always lived. The only thing that annoys me is that we have lost our outhouse. Yes, death and destruction! It’s on the other side of the chasm now, and I’m sorry for anyone who can’t contain himself until we manage to build a new one.”

But that was soon dealt with, and life in Matt’s Fort went on exactly as before—except that now there was a child there. A little child, who succeeded bit by bit in sending Matt and all his robbers more or less mad, in Lovis’s view. Not that it hurt them to become a little gentler-handed and milder-mannered, but there should be moderation in all things. And it really was strange to see twelve robbers and one robber chieftain sitting there like a lot of sheep, beaming and blissful just because a small child had learned to crawl around the stone hall, as if there had never been a greater miracle on earth. It was true that Ronia scampered about unusually fast because she had a trick of pushing off with her left foot, which the robbers thought absolutely astounding. But, after all, most children do learn to crawl, as Lovis said, without loud cheers, and without their father seeing it as a reason to forget everything else and positively neglect his work.

“Do you want Borka to take over all the robbing in Matt’s Forest as well?” she asked sharply, when the robbers, with Matt at their head, came storming home early just because they had to see Ronia eating her porridge before Lovis put her into her hanging cradle for the night.

But Matt had no ears for such talk.

“Ronia mine, my little pigeon, ” he shouted, as Ronia, shoving hard with her left foot, came shooting across the floor toward him as soon as he walked in the door. And he sat with his little pigeon on his knee and fed her her porridge while his twelve robbers looked on. The porridge bowl was standing on the hearth at arm’s reach, and as Matt was rather clumsy with his rough robber’s fists, a lot of porridge got spilled on the floor, and Ronia knocked the spoon from time to time, so that a good deal of porridge also flew onto Matt’s eyebrows. The first time it happened, the robbers laughed so uproariously that Ronia was frightened and began to cry, but she soon realized that she had hit on something amusing to do, and did it again, which delighted the robbers more than it amused Matt. But otherwise Matt thought that everything Ronia did was incomparable and that she herself had not her equal on earth.

Even Lovis had to laugh when she saw Matt sitting there with his child on his knee and porridge on his eyebrows.

“My dear Matt, who would ever think that you were the most powerful robber chieftain in all the woods and mountains! If Borka saw you now, he would split his sides laughing. “

“I’d soon put a stop to that, ” Matt said calmly.

Borka—Borka was the archenemy. Just as Borka’s father and grandfather had been the archenemies of Matt’s father and grandfather—yes, since time immemorial the Borkas and the Matts had been at loggerheads. They had always been robbers and a terror to decent folk who had to pass with their horses and wagons through the deep forests where the robbers lurked.

“God help anyone whose way lies along Robbers’ Walk, ” people said, talking of the narrow mountain pass between Borka’s Wood and Matt’s Wood. There were always robbers on the lookout there, and whether they were Borka’s robbers or Matt’s robbers made little difference, at least to those who were robbed. But to Matt and Borka the difference was enormous. They fought for their lives over the booty and even robbed each other without hesitation if there were not enough merchants passing through Robbers’ Walk.

Ronia knew nothing of all this; she was too young. She did not know that her father was a feared robber chieftain. To her, he was just the kind, bearded Matt, who laughed and sang and shouted and gave her porridge, and whom she loved.

But she was growing up every day, and soon she began to explore the world around her. For a long time she had believed that the great stone hall was the whole world. And she liked it there; she was safe sitting under the great long table, playing with pebbles and pinecones that Matt brought home to her. And the stone hall was not a bad place for a child. You could have great fun there, and you could learn a lot.

Ronia liked it when the robbers sang around the fire in the evenings. She sat quietly under the table, listening, until she knew all the robbers’ ditties by heart. Then she joined in, her voice clear as a bell, and Matt was astonished at his matchless child, who sang so well. She taught herself to dance, too. If the robbers were in the mood, they would dance and leap around the room like madmen, and Ronia soon saw what to do. She danced and bounded and made robber leaps as well, to Matt’s delight, and when afterward the robbers threw themselves down at the long table to slake their thirst with a tankard of beer, he bragged about his daughter.

“She’s as beautiful as a wild harpy, I’d have you know! As supple, as dark-eyed, and as black-haired. You never saw such a splendid child in your lives, I’d have you know! “

And the robbers nodded and agreed with him. But Ronia sat silently under the table with her pebbles and pinecones, and when she saw the robbers’ feet in their shaggy fur slippers, she pretended that they were her unruly goats. She had seen some in the goat shed, where Lovis took her when she did the milking.

But Ronia had seen little more than this during her short life. She knew nothing of what lay outside Matt’s Fort. And one fine day Matt realized—however little he liked it—that the time had come.

“Lovis, ” he said to his wife, “our child must learn what it’s like living in Matt’s Forest. Let her go! “

“Ah, so you’ve seen it at last, ” said Lovis. “It would have happened long ago if I’d had my way. “

And from then on Ronia was free to wander at will. But first Matt had one or two things to say to her.

“Watch out for wild harpies and gray dwarfs and Borka robbers, ” he said.

“How will I know which are wild harpies and gray dwarfs and Borka robbers? ” asked Ronia.

“You’ll find out, ” Matt said.

“All right, ” said Ronia.

“And watch out you don’t get lost in the forest, ” said Matt.

What shall I do if I get lost in the forest? ” Ronia asked.

“Find the right path, ” Matt said.

“All right, ” said Ronia.

“And watch out you don’t fall in the river, ” Matt said.

“What shall I do if I fall in the river? ” Ronia asked.

“Swim, ” Matt said.

“All right, ” said Ronia.

“And watch out you don’t tumble into Hell’s Gap, ” Matt said.

He meant the chasm that split Matt’s Fort in two.

“What shall I do if I tumble into Hell’s Gap? ” Ronia asked.

“You won’t be doing anything else, ” Matt said, and then he gave a bellow, as if all things evil had suddenly pierced his heart.

“All right, ” said Ronia when Matt had finished bellowing. “I shan’t fall into Hell’s Gap. Is there anything else? “

“There certainly is, ” said Matt. “But you’ll find out bit by bit. Go now! “

Two

so ronia went. she soon realized how stupid she had been: how could she have thought that the great stone hall was the whole world? Not even the huge

Matt’s Fort was the whole world. Not even the high Matt’s Mountain was the whole world—no, the world was bigger than Matt. It was so big that it took your breath away. Of course, she had heard Matt and Lovis talking about things beyond Matt’s Fort; they had talked of the river. But it was not until she could see how it came rushing in wild rapids from deep under Matt’s Mountain that she understood what rivers were. They had talked about the forest. But it was not until she saw it, so dark and mysterious, with all its rustling trees, that she understood what forests were, and she laughed silently because rivers and forests were there. She could scarcely believe it.

She followed the path straight into the wildest woods and came to the lake. Matt had told her that she must not go farther than that And the lake lay there, black among the dark pines. Only the water lilies floating on its surface gleamed white. Ronia did not know that they were water lilies, but she looked at them for a long time and laughed silently because water lilies were there.

She stayed by the lake all day and did many things there that she had never tried before. She threw pinecones into the water and tried to see if she could make them bob away just by splashing with her feet. She had never had such fun before. Her feet felt so glad and free when she made them splash, and gladder still when she made them climb. There were great mossy boulders around the pool to climb on, and pine trees and fir trees to clamber in. Ronia climbed and clambered until the sun began to sink behind the wooded ridges. Then she ate the bread and drank the milk she had brought with her. She lay down on the moss to rest for a while, and the trees rustled high above her head. She lay there watching them and laughed silently because they were there. Then she fell asleep.

When she woke up, the evening had grown dark and she could see the stars burning above the treetops. Then she realized that there was even more to the world than she had thought. And it made her sad that stars were there but she could never reach them, no matter how far she stretched her arms toward them.

Now she had been in the forest longer than she was allowed. Now she must go home; otherwise, she knew, Matt would be out of his mind.