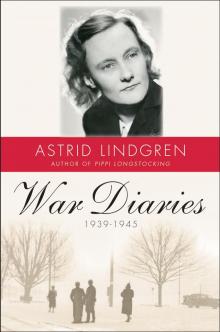

War Diaries, 1939-1945

Astrid Lindgren

War Diaries, 1939–1945

War Diaries 1939–1945

Krigsdagböcker 1939–1945

Astrid Lindgren

Translated from the Swedish by Sarah Death

With a foreword by Karin Nyman

First published in the United States in 2016 by Yale University Press. First published in Great Britain in 2016 by Pushkin Press. First published in 2015 as Krigsdagböcker 1939–1945

by Salikon Förlag, Sweden.

For more information about Astrid Lindgren, see www.astridlindgren.com.

All foreign rights are handled by Saltkråkan AB, Lidingö, Sweden.

© Astrid Lindgren/Saltkråkan AB.

The translation was supported by a grant from the Swedish Arts Council.

Illustration credits: Reproduction of the diaries © Andrea Davis Kronlund, The National Library of Sweden, Stockholm. Illustration on p. 6 Ricard Estay. All other illustrations courtesy of Saltkråkan AB.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office).

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016952135

ISBN 978-0-300-22004-9 (hardcover: alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Foreword by Karin Nyman

Translator’s Note

Diary 1939

Diary 1940

Diary 1941

Diary 1942

Diary 1943

Diary 1944

Diary 1945

Glossary of Names

Foreword

by Karin Nyman

I was five at the outbreak of the Second World War. For us children in Sweden it soon started to feel like a normal state of affairs, almost a natural state, for all those around us to be at war. We took it for granted that our country had somehow secured guarantees not to be involved, and it was constantly being stressed to us: No, no, don’t be scared, the war won’t be coming to Sweden. It felt special, but in some strange way reasonable and justified, for us to be the ones who were spared.

It did not seem strange to me that my mother cut articles out of the papers and pasted them into exercise books; I assumed it was just something parents did. Now I know that she was very probably unique, a 32-year-old housewife with secretarial training but no experience of thinking in political terms, who was so determined to document what was happening in Europe and the world to her own satisfaction that she persisted with her cuttings and commentaries for all six years of the war. It is also extremely rare and special to find diary entries so well written that they can be reproduced unabridged and instantly make gripping reading.

That is why Salikon Förlag originally wanted to publish them, of course, because they give such a good picture of ordinary family life in Sweden in the war years and so vividly express the despair of the powerless at the horrors they read about in the papers every morning. Daily papers were the primary news source, there was no television, and although there was radio it had no live broadcasting or correspondents – the radio news consisted of readings of the telegrams received from the Swedish news agency Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå (TT).

After the first year of the war, however, Astrid gained access to a fresh source of information. She was offered state security work at the secret Postal Control Division, as a censor of military and private post sent to, and coming from, other counties. The letters had to be steamed open and read, the aim being to find and black out any locations of military importance or other classified information. It was all so hush-hush that we children never knew what her late-evening job was. But the restrictions did not prevent her from copying out, or quoting sections of, the more interesting letters in her diary, for the insight they gave into conditions in the occupied countries.

The diaries show another side of Astrid Lindgren’s authorship. She was admittedly still not a published author, nor had she any intention of becoming one. But in the midst of the convulsive tensions of the time, at some point in the winter of 1941, she started coming out with her unbridled stories of wild, freedom-loving Pippi Longstocking – first as a bedtime story for me, then at any time of day, for a growing audience of children, her own and others’, all wanting to hear more. In early 1944, she wrote down some of the stories and made them into a book. It was published by Rabén & Sjögrens Förlag in 1945, having first being refused by Bonniers. That was how it all began. It rather takes your breath away to think that before that relatively recent date, Pippi Longstocking simply did not exist and Astrid Lindgren could not have had the faintest idea of the career as a children’s writer which lay ahead of her.

And that she, and we, did not know was probably just as well! How utterly unreal a glimpse of her future global fame would have seemed to her then. I can imagine that she might have looked away in terror at the sight of it. In old age, with her renown a fait accompli and her eyesight too poor for her to read the piles of readers’ thank-you letters and their touching testaments to the crucial role some of her books had played in their lives, when I had to read the letters out loud to her, she would sometimes look up, interrupt me and say, sounding almost fearful: ‘But this is remarkable, don’t you think?’ ‘Well yes,’ I would say, because I did. Truly remarkable.

Translator’s Note

Until 2013, seventeen leather-bound diaries lived in a wicker laundry basket at Astrid Lindgren’s familiar home address, 46 Dalagatan in Stockholm. The diaries cover the years 1939–45. Her own name for them was ‘The War Diaries’ and they are now accessible to the public for the first time. The diaries bulged with press cuttings, pasted in between Lindgren’s handwritten entries. She refers now and then to the time it has taken her to save newspapers and magazines, sift through them and select items to cut out for pasting into her notebooks, but it was a task she set herself and she carried it through to the end, the number of cuttings increasing with every passing wartime year. In her preface to the Swedish edition, Kerstin Ekman, another eminent Swedish writer, expresses her admiration for Lindgren’s unusual resolve:

War diaries were kept by general staffs and units out in the field. Their operational maps, battle accounts and observations would form the foundation of future history writing. It is striking to think of this 32-year-old mother of two and office-worker taking on the same sort of task with such seriousness. But only for herself, to try to understand what was going on.

The Swedish edition includes facsimiles of quite a number of the two-page diary spreads featuring pasted-in newspaper cuttings. Here and there in this edition the reader will come across references to such accompanying cuttings and Pushkin Press has asked me to provide an explanatory note wherever one is necessary.

Astrid Lindgren’s own comments are in round brackets, whereas square brackets indicate clarifications added by the Swedish editors, with a few additions for this English-language edition, to provide a little more background information for a non-Swedish readership.

The ambition was to retain the overall character of the original, but dates and abbreviations have been harmonized. Biographical names have been corrected and some place names have been put into English. Where the o

riginal work was in English, or in long lists of Swedish works, book and film titles have also been rendered in English.

Then as now, Swedes often use ‘England’ as shorthand for any part of the British Isles, and that is Lindgren’s practice throughout her diaries. It seemed less jarring to render this as ‘Britain’ in the English-language edition.

SARAH DEATH

1939

Astrid and her husband Sture at home in Vulcanusgatan, 1939.

1 SEPTEMBER 1939

Oh! War broke out today. Nobody could believe it.

Yesterday afternoon, Elsa Gullander and I were in Vasa Park with the children running and playing around us and we sat there giving Hitler a nice, cosy telling-off and agreed that there definitely was not going to be a war – and now today! The Germans bombarded several Polish cities early this morning and are forging their way into Poland from all directions. I’ve managed to restrain myself from any hoarding until now, but today I laid in a little cocoa, a little tea, a small amount of soap and a few other things.

A terrible despondency weighs on everything and everyone. The radio churns out news reports all day long. Lots of our men are being called up. There’s a ban on private motoring, too. God help our poor planet in the grip of this madness!

2 SEPTEMBER

A sad, sad day! I read the war announcements and felt sure Sture would be called up but he turned out not to be, in the end. Countless others have got to leave home and report for duty, though. We’re in a state of ‘intensified war readiness’. The amount of stockpiling is unbelievable, according to the papers. People are mainly buying coffee, toilet soap, household cleaning soap and spices. There’s apparently enough sugar in the country to last us 15 months, but if nobody can resist stocking up we’ll have a shortage anyway. At the grocer’s there wasn’t a single kilo of sugar to be had (but they’re expecting more in, of course).

When I went to my coffee merchant to buy a fully legitimate quarter-kilo of coffee, I found a notice on the door: ‘Closed. Sold out for today.’

It’s Children’s Day today, and dear me, what a day for it! I took Karin up to the park this afternoon and that was when I saw the official notice that all men born in 1898 [Sture’s year of birth] would be called up. I tried to read the newspaper while Karin went on the slide but I couldn’t, I just sat there with tears rising in my throat.

People look pretty much as usual, only a bit more gloomy. Everybody talks about the war all the time, even people who don’t know each other.

3 SEPTEMBER

The sun is shining, it’s a nice warm day, this earth could be a lovely place to live. At 11 a.m. today Britain declared war on Germany, as did France, but I don’t know exactly what time. Germany had received an ultimatum from Britain demanding an undertaking by 11 o’clock to withdraw its troops from Poland and enter into talks, in which case the invasion of Poland would be deemed never to have happened. But no undertaking had been received by 11 o’clock and Chamberlain said in his speech to the British nation on this Sunday afternoon: ‘consequently this country is at war with Germany’.

‘Responsibility [...] lies on the shoulders of one man,’ Chamberlain told the British parliament. And history’s judgment of Hitler will certainly be damning – if this turns into another world war. Many people see this quite simply as the fall of the white race and of civilization.

The various governments are already jawing about who’s to blame. Germany claims that Poland attacked first and that the Poles could do whatever they wanted under the protection of the Anglo-French guarantee. Here in Sweden we can’t see it any other way than that Hitler wants war, or that he can’t see any means to avoid it without losing face. It’s pretty clear that Chamberlain did his utmost to keep the peace; he gave way in Munich for no other reason. This time, Hitler demanded ‘Danzig and the Corridor’ but deep down he probably wants to rule the whole world. What line should Italy and Russia take? Polish sources say the first two days of war cost 1,500 lives in Poland.

4 SEPTEMBER

Anne-Marie came round this evening and we have never had a more dismal ‘meeting’. We tried to talk about things other than the war, but it was impossible. In the end we had a brandy to cheer ourselves up, but it didn’t help.

A big British passenger steamer with 1,400 people on board has been torpedoed by the Germans, who deny having done it and claim the ship must have run into a mine. But the British wouldn’t have laid mines off the north-west coast of Scotland. I believe all the surviving passengers were rescued (60 died, no, more, 128?), some of them by Wenner-Gren on the Southern Cross, out on a pleasure trip with his tanks full of the oil he’s been hoarding. He’s been scolded roundly in the press for his crazy stockpiling.

The British mounted a bombing raid over Germany and dropped not bombs but leaflets – saying that the British people don’t want to be at war with the German people, only with the Nazi regime. The British presumably hope there’ll be a revolution in Germany. It’ll annoy Hitler, at any rate. He’s decreed hard labour for anyone caught listening to foreign radio stations and the death penalty for those spreading information from foreign broadcasts to other citizens.

A bomb from an unidentified plane fell on Esbjerg in peaceable little Denmark, destroyed a house and killed two people, one of them a woman.

The bus service in Stockholm is to be restricted from tomorrow. Our streets already look deserted, now that use of private cars has been banned.

Today I assembled my little stockpile in a corner of the kitchen, ready for storage in the attic. It comprises: 2kg sugar, 1kg sugar lumps, 3kg rice, 1kg potato flour, 11/2kg coffee in various tins, 2kg household cleaning soap, 2 boxes Persil, 3 bars toilet soap, 5 packets cocoa, 4 packets tea and a few spices. I shall gradually try to collect up a bit more, because prices are bound to rise soon. Karin called for a drink of water after I put her to bed last night. ‘At least we don’t have to worry about saving water.’ She thought we’d be able to live on water and jam if we had a war.

5 SEPTEMBER

Chamberlain delivered a radio address to the German people – who aren’t allowed to listen.

There’s still nothing happening on the western front. But it seems clear that Germany is giving Poland a good thrashing.

I bought shoes for myself and the kids, before the prices go up: two pairs for Karin at 12.50 kronor a pair, one pair for Lasse at 19.50 and one pair for me at 22.50.

6 SEPTEMBER

They say the French put up placards on the western front: ‘We won’t shoot.’ And that the Germans replied on their placards: ‘Nor will we!’ But it can’t be true.

From tomorrow, all heavy goods vehicles will be subject to restrictions, as well.

7 SEPTEMBER

All quiet at the Schipka Pass [on the Swedish island of Gotska Sandön, strategically placed in the Baltic]. But the Germans will soon be in Warsaw.

8 SEPTEMBER

Yes, they’ve made it. Poor Poland! The Poles maintain that if the Germans were able to take Warsaw, it means the last Polish soldier has been crushed.

17 SEPTEMBER

The Russians marched into Poland today as well, ‘to safeguard the interests of the Russian minority’. Poland’s now as far down on its knees as it can get, so they must be thinking of sending a negotiator to Germany.

There’s still not much action on the western front, but according to today’s paper Hitler’s planning a huge air offensive against Britain. We hear of very worrying developments at sea: countless ships torpedoed or blown up by mines. Supply routes to Germany must be more or less cut off, I think.

3 OCTOBER

The war carries on as usual. Poland has surrendered. It’s total chaos there. Germany and Russia have divided the country between them. It seems simply incredible that such a thing can happen in the twentieth century.

Russia is the one benefiting most from this war. Once the Germans had crushed Poland – only then did the Russians march in and take their share of the spoils, and no small

share, either. It’s generally assumed that the Germans aren’t particularly happy about this state of affairs, but they can’t say anything. Russia’s making a whole series of demands in the Baltic states – and getting what it wants.

There can be no doubt that Germany is waging war on us, the neutral countries. All our ships in the North Sea are being captured and sunk. They’ve got spies in the ports checking up on cargoes and destinations, and we’re not the only neutral country whose ships are being sunk. I can’t see what they hope to achieve.

There’s still nothing much happening on the western front.

Here at home, we have various minor inconveniences to cope with. There’s no white sewing thread to be had, for instance. And we’re only allowed a quarter-kilo of household soap at a time.

Lots of people are now unemployed as a result of the crisis. It’s a shame nobody’s shot Hitler. The coming week is going to be ‘dramatic’, Germany and Britain have both promised. Germany’s expected to propose a peace treaty that Britain can’t accept. But people all over the world want peace.

14 OCTOBER

The punch-up has started in earnest and it affects us now, primarily Finland of course, but it’s only a short step from there to here. Russia’s ‘invited’ the foreign ministers of the Baltic states to Moscow, one by one, and now it’s Finland’s turn. Foreign Minister Paasikivi is spending several days with Stalin, keeping Finland, us and the whole world in suspense. Helsinki has evacuated large sections of its population and the country is preparing for a war it would dearly have loved to avoid. The solidarity of the Nordic peoples is greater than ever. King Gustaf has invited all the Nordic heads of state to a conference in Stockholm next week. For now, Finland is putting its trust in Sweden. We’re expecting general mobilization here soon. Lars has come home from school with a list of kit he’ll need if they are evacuated and Mrs Stäckig and I went to PUB [department store] today to buy rucksacks and underwear for our lads.