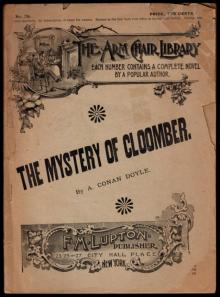

The Mystery of Cloomber

Arthur Conan Doyle

Produced by Lionel G. Sear

THE MYSTERY OF CLOOMBER

By Arthur Conan Doyle

CONTENTS

I THE HEGIRA OF THE WESTS FROM EDINBURGH

II OF THE STRANGE MANNER IN WHICH A TENANT CAME TO CLOOMBER

III OF OUR FURTHER ACQUAINTANCE WITH MAJOR-GENERAL J. B. HEATHERSTONE

IV OF A YOUNG MAN WITH A GREY HEAD

V HOW FOUR OF US CAME TO BE UNDER THE SHADOW OF CLOOMBER

VI HOW I CAME TO BE ENLISTED AS ONE OF THE GARRISON OF CLOOMBER

VII OF CORPORAL RUFUS SMITH AND HIS COMING TO CLOOMBER

VIII STATEMENT OF ISRAEL STAKES

IX NARRATIVE OF JOHN EASTERLING, F.R.C.P. EDIN.

X OF THE LETTER WHICH CAME FROM THE HALL

XI OF THE CASTING AWAY OF THE BARQUE "BELINDA"

XII OF THE THREE FOREIGN MEN UPON THE COAST

XIII IN WHICH I SEE THAT WHICH HAS BEEN SEEN BY FEW

XIV OF THE VISITOR WHO RAN DOWN THE ROAD IN THE NIGHT-TIME

XV THE DAY-BOOK OF JOHN BERTHIER HEATHERSTONE

XVI AT THE HOLE OF CREE

CHAPTER I. THE HEGIRA OF THE WESTS FROM EDINBURGH

I John Fothergill West, student of law in the University of St. Andrews,have endeavoured in the ensuing pages to lay my statement before thepublic in a concise and business-like fashion.

It is not my wish to achieve literary success, nor have I any desire bythe graces of my style, or by the artistic ordering of my incidents, tothrow a deeper shadow over the strange passages of which I shall haveto speak. My highest ambition is that those who know something of thematter should, after reading my account, be able to conscientiouslyindorse it without finding a single paragraph in which I have eitheradded to or detracted from the truth.

Should I attain this result, I shall rest amply satisfied with theoutcome of my first, and probably my last, venture in literature.

It was my intention to write out the sequence of events in due order,depending on trustworthy hearsay when I was describing that which wasbeyond my own personal knowledge. I have now, however, through thekind cooperation of friends, hit upon a plan which promises to be lessonerous to me and more satisfactory to the reader. This is nothing lessthan to make use of the various manuscripts which I have by me bearingupon the subject, and to add to them the first-hand evidence contributedby those who had the best opportunities of knowing Major-General J. B.Heatherstone.

In pursuance of this design I shall lay before the public the testimonyof Israel Stakes, formerly coachman at Cloomber Hall, and ofJohn Easterling, F.R.C.P. Edin., now practising at Stranraer, inWigtownshire. To these I shall add a verbatim account extracted fromthe journal of the late John Berthier Heatherstone, of the events whichoccurred in the Thul Valley in the autumn of '41 towards the end ofthe first Afghan War, with a description of the skirmish in the Teradadefile, and of the death of the man Ghoolab Shah.

To myself I reserve the duty of filling up all the gaps and chinks whichmay be left in the narrative. By this arrangement I have sunk from theposition of an author to that of a compiler, but on the other handmy work has ceased to be a story and has expanded into a series ofaffidavits.

My Father, John Hunter West, was a well known Oriental and Sanskritscholar, and his name is still of weight with those who are interestedin such matters. He it was who first after Sir William Jones calledattention to the great value of early Persian literature, and histranslations from the Hafiz and from Ferideddin Atar have earned thewarmest commendations from the Baron von Hammer-Purgstall, of Vienna,and other distinguished Continental critics.

In the issue of the _Orientalisches Scienzblatt_ for January, 1861,he is described as _"Der beruhmte und sehr gelhernte Hunter West vonEdinburgh"_--a passage which I well remember that he cut out and stowedaway, with a pardonable vanity, among the most revered family archives.

He had been brought up to be a solicitor, or Writer to the Signet, asit is termed in Scotland, but his learned hobby absorbed so much of histime that he had little to devote to the pursuit of his profession.

When his clients were seeking him at his chambers in George Street, hewas buried in the recesses of the Advocates' Library, or poring oversome mouldy manuscript at the Philosophical Institution, with his brainmore exercised over the code which Menu propounded six hundred yearsbefore the birth of Christ than over the knotty problems of Scottish lawin the nineteenth century. Hence it can hardly be wondered at thatas his learning accumulated his practice dissolved, until at the verymoment when he had attained the zenith of his celebrity he had alsoreached the nadir of his fortunes.

There being no chair of Sanscrit in any of his native universities, andno demand anywhere for the only mental wares which he had to disposeof, we should have been forced to retire into genteel poverty, consolingourselves with the aphorisms and precepts of Firdousi, Omar Khayyam, andothers of his Eastern favourites, had it not been for the kindnessand liberality of his half-brother William Farintosh, the Laird ofBranksome, in Wigtownshire.

This William Farintosh was the proprietor of a landed estate, theacreage which bore, unfortunately, a most disproportional relation toits value, for it formed the bleakest and most barren tract of landin the whole of a bleak and barren shire. As a bachelor, however, hisexpenses had been small, and he had contrived from the rents of hisscattered cottages, and the sale of the Galloway nags, which he bredupon the moors, not only to live as a laird should, but to put by aconsiderable sum in the bank.

We had heard little from our kinsman during the days of our comparativeprosperity, but just as we were at our wit's end, there came a letterlike a ministering angel, giving us assurance of sympathy and succour.In it the Laird of Branksome told us that one of his lungs had beengrowing weaker for some time, and that Dr. Easterling, of Stranraer, hadstrongly advised him to spend the few years which were left to him insome more genial climate. He had determined, therefore to set out forthe South of Italy, and he begged that we should take up our residenceat Branksome in his absence, and that my father should act as his landsteward and agent at a salary which placed us above all fear of want.

Our mother had been dead for some years, so that there were only myself,my father, and my sister Esther to consult, and it may be readilyimagined that it did not take us long to decide upon the acceptanceof the laird's generous offer. My father started for Wigtown that verynight, while Esther and I followed a few days afterwards, bearing withus two potato-sacksful of learned books, and such other of our householdeffects that were worth the trouble and expense of transport.