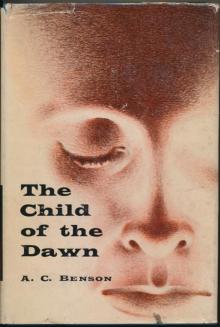

The Child of the Dawn

Arthur Christopher Benson

Produced by Audrey Longhurst, Mary Meehan and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team.

THE CHILD OF THE DAWN

By ARTHUR CHRISTOPHER BENSON

FELLOW OF MAGDALENE COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE

[Greek: edu ti tharsaleais ton makron teiein bion elpisin]

Author of THE UPTON LETTERS, FROM A COLLEGE WINDOW, BESIDE STILL WATERS,THE ALTAR FIRE, THE SCHOOLMASTER, AT LARGE, THE GATE OF DEATH, THESILENT ISLE, JOHN RUSKIN, LEAVES OF THE TREE, CHILD OF THE DAWN, PAULTHE MINSTREL

1912

To MY BEST AND DEAREST FRIENDHERBERT FRANCIS WILLIAM TATHAMIN LOVE AND HOPE

INTRODUCTION

I think that a book like the following, which deals with a subject sogreat and so mysterious as our hope of immortality, by means of anallegory or fantasy, needs a few words of preface, in order to clearaway at the outset any misunderstandings which may possibly arise in areader's mind. Nothing is further from my wish than to attempt anyphilosophical or ontological exposition of what is hidden behind theveil of death. But one may be permitted to deal with the subjectimaginatively or poetically, to translate hopes into visions, as I havetried to do.

The fact that underlies the book is this: that in the course of a verysad and strange experience--an illness which lasted for some two years,involving me in a dark cloud of dejection--I came to believepractically, instead of merely theoretically, in the personalimmortality of the human soul. I was conscious, during the whole time,that though the physical machinery of the nerves was out of gear, thesoul and the mind remained, not only intact, but practically unaffectedby the disease, imprisoned, like a bird in a cage, but perfectly free inthemselves, and uninjured by the bodily weakness which enveloped them.This was not all. I was led to perceive that I had been living lifewith an entirely distorted standard of values; I had been ambitious,covetous, eager for comfort and respect, absorbed in trivial dreams andchildish fancies. I saw, in the course of my illness, that what reallymattered to the soul was the relation in which it stood to other souls;that affection was the native air of the spirit; and that anything whichdistracted the heart from the duty of love was a kind of bodilydelusion, and simply hindered the spirit in its pilgrimage.

It is easy to learn this, to attain to a sense of certainty about it,and yet to be unable to put it into practice as simply and frankly asone desires to do! The body grows strong again and reasserts itself; butthe blessed consciousness of a great possibility apprehended and graspedremains.

There came to me, too, a sense that one of the saddest effects ofwhat is practically a widespread disbelief in immortality, whichaffects many people who would nominally disclaim it, is that we thinkof the soul after death as a thing so altered as to be practicallyunrecognisable--as a meek and pious emanation, without qualities or aimsor passions or traits--as a sort of amiable and weak-kneed sacristan inthe temple of God; and this is the unhappy result of our so often makingreligion a pursuit apart from life--an occupation, not an atmosphere; sothat it seems impious to think of the departed spirit as interested inanything but a vague species of liturgical exercise.

I read the other day the account of the death-bed of a great statesman,which was written from what I may call a somewhat clerical point ofview. It was recorded with much gusto that the dying politician took nointerest in his schemes of government and cares of State, but foundperpetual solace in the repetition of childish hymns. This fact had, ormight have had, a certain beauty of its own, if it had been expresslystated that it was a proof that the tired and broken mind fell back uponold, simple, and dear recollections of bygone love. But there wasmanifest in the record a kind of sanctimonious triumph in the extinctionof all the great man's insight and wisdom. It seemed to me that theright treatment of the episode was rather to insist that those greatqualities, won by brave experience and unselfish effort, were onlytemporarily obscured, and belonged actually and essentially to thespirit of the man; and that if heaven is indeed, as we may thankfullybelieve, a place of work and progress, those qualities would be activelyand energetically employed as soon as the soul was freed from thetrammels of the failing body.

Another point may also be mentioned. The idea of transmigration andreincarnation is here used as a possible solution for the extremedifficulties which beset the question of the apparently fortuitousbrevity of some human lives. I do not, of course, propound it asliterally and precisely as it is here set down--it is not a forecast ofthe future, so much as a symbolising of the forces of life--but _therenewal of conscious experience_, in some form or other, seems to be theonly way out of the difficulty, and it is that which is here indicated.If life is a probation for those who have to face experience andtemptation, how can it be a probation for infants and children, who diebefore the faculty of moral choice is developed? Again, I find it veryhard to believe in any multiplication of human souls. It is even moredifficult for me to believe in the creation of new souls than in thecreation of new matter. Science has shown us that there is no actualaddition made to the sum of matter, and that the apparent creation ofnew forms of plants or animals is nothing more than a rearrangement ofexisting particles--that if a new form appears in one place, it merelymeans that so much matter is transferred thither from another place. Ifind it, I say, hard to believe that the sum total of life is actuallyincreased. To put it very simply for the sake of clearness, andaccepting the assumption that human life had some time a beginning onthis planet, it seems impossible to think that when, let us say, the twofirst progenitors of the race died, there were but two souls in heaven;that when the next generation died there were, let us say, ten souls inheaven; and that this number has been added to by thousands andmillions, until the unseen world is peopled, as it must be now, if noreincarnation is possible, by myriads of human identities, who, aftera single brief taste of incarnate life, join some vast community ofspirits in which they eternally reside. I do not say that this latterbelief may not be true; I only say that in default of evidence, it seemsto me a difficult faith to hold; while a reincarnation of spirits, ifone could believe it, would seem to me both to equalise the inequalitiesof human experience, and give one a lively belief in the virtue andworth of human endeavour. But all this is set down, as I say, in atentative and not in a philosophical form.

And I have also in these pages kept advisedly clear of Christiandoctrines and beliefs; not because I do not believe wholeheartedly inthe divine origin and unexhausted vitality of the Christian revelation,but because I do not intend to lay rash and profane hands upon thehighest and holiest of mysteries.

I will add one word about the genesis of the book. Some time ago Iwrote a number of short tales of an allegorical type. It was a curiousexperience. I seemed to have come upon them in my mind, as one comesupon a covey of birds in a field. One by one they took wings and flew;and when I had finished, though I was anxious to write more tales, Icould not discover any more, though I beat the covert patiently todislodge them.

This particular tale rose unbidden in my mind. I was never consciousof creating any of its incidents. It seemed to be all there from thebeginning; and I felt throughout like a man making his way along a road,and describing what he sees as he goes. The road stretched ahead of me;I could not see beyond the next turn at any moment; it just unrolleditself inevitably and, I will add, very swiftly to my view, and was thusa strange and momentous experience.

I will only add that the book is all based upon an intense belief inGod, and a no less intense conviction of personal immortality andpersonal responsibility. It aims at bringing out the fact that our lifeis a very real pilgrimage to high and far-off things from mean andsordid beginnings, and that the key of the mystery lies in the frankfaci

ng of experience, as a blessed process by which the secret purposeof God is made known to us; and, even more, in a passionate belief inLove, the love of friend and neighbour, and the love of God; and in theabsolute faith that we are all of us, from the lowest and most degradedhuman soul to the loftiest and wisest, knit together with chains ofinfinite nearness and dearness, under God, and in Him, and through Him,now and hereafter and for evermore.

A.C.B.

THE OLD LODGE, MAGDALENE COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, _January_, 1912.