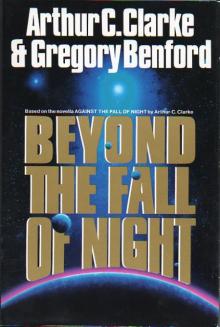

Beyond the Fall of Night

Arthur C. Clarke

Beyond the Fall of Night

To Mark Martin and David Brin

For tangy ideas, zesty talk, warm friendship

G.B.

F O R E W O R D

P R O L O G U E

1

2

3

4

5

6

7.

8

9

10.

11

12.

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

F O R E W O R D

It is now more than half a century since Against the Fall of Night was born, yet the moment of conception is still clear in my memory. Out of nowhere, it seems, the opening image of the novel suddenly appeared to me. It was so vivid that I wrote it down at once, though at the time I had no idea that I would ever develop it any further.

That would have been in 1936, plus or minus a year, and I had written several drafts by late 1940, when I was evacuated with my colleagues in His Majesty's Exchequer and Audit Department to the small North Wales town of Colwyn Bay. Here I finished a 15,000-word version, but for the next five years was somewhat preoccupied with other matters (see Glide Path). I started work on-it again in August 1945: whether before or after Hiroshima changed the world, I do not now recall.

The first complete draft was finished by January 1946, and promptly sent to John Campbell at Astounding Stories. He took three months to reject it, and I rewrote the ending in July 1946, submitting it again to Campbell. He took another three months to reject the second version.

After that, I sent it to my new agent, Scott Meredith, who sold it to Startling Stories, where it appeared in November 1948. It was accepted by Gnome Press for hardcover pubhcation in September 1949, and was pubhshed in a handsome edition with a jacket by promising new artist, one Kelly Freas (it must have been one of Kelly's earliest commissions; I only hope that he was paid for it!).

Because it was my firstborn, Against the Fall of Night always had a special place in my affections, yet I was never completely satisfied with it. The opportunity to make a complete revision came during a long sea voyage from England to Australia, when I joined forces with Mike Wilson and set off on an underwater expedition to the Great Barrier Reef (see The Coast of Coral). The much longer and drastically revised novel, The City and the Stars, was completed in Queensland between excursions to the Reef and the Torres Strait pearling grounds. It was published by Harcourt, Brace & World in 1956, and has remained in print ever since.

At the time, I assumed that new version would completely replace the older novel, but Against the Fall of Night showed no tendency to fade away; indeed, to my slight chagrin, some readers preferred it to its successor, and it has now been reissued several times in paperback (Pyramid Books, 1960: Jove, 1978) as well as in the volume The Lion of Comarre and Against the Fall of Night (Harcourt, Brace & World; Victor GoUancz, 1970). One day I would like to conduct a poll to discover which is the more popular version; I have long ago given up trying to decide which is the better one.

The search for a title took almost as long as the writing of the book. I found it at last in a poem of A. E. Housman's, which also inspired the short story Transience:

What shall I do or write Against the fall of night?

The name of my protagonist, Alvin, also gave me many headaches, and I cannot remember when—or why—I decided on it. I did not realize that, at least to American readers, it was faintly humorous, being redolent of a well-known comic strip. However, many years later, the name had two enormously important associations for me. The deep submersible Alvin took Ballard and his associates to the wreck of the Titanic when it was discovered in 1986. That tragedy, though it occurred five years before I was born (that dates me, doesn't it?) has haunted me all my life. It was the basis of the very first story I ever wrote, a luckily long-lost epic called—wait for it—"Icebergs of Space." I also incorporated it into the novel Imperial Earth (1975) and it is the subject of a book that has now occupied me for several years.

Perhaps still stranger, the name Alvin is derived from that of Allyn C. Vine, its principal engineer. And was one of the authors of the famous letter in Science {151 682-683; 1966) which proposed the construction of the Space Elevator—the subject of my novel The Fountains of Paradise (1979). So the name Alvin had more power than I could possibly have imagined in the late 1930s, and I am happy to salute it.

When the suggestion was made that Gregory Benford should write a sequel continuing the story, I was immediately taken by the idea, because I had long admired Greg's writing—especially his remarkable Great Sky River. As it happened, I'd also just met him at NASA headquarters; as Professor of Astrophysics at the University of California, Irvine, he is one of NASA's technical advisers.

I have now read his sequel with great enjoyment, because to me—as it will be to you—it was a voyage of discovery. I had no idea how he would develop the themes and characters I had abandoned so long ago. It's particularly interesting to see how some of the concepts of this half-century-old story are now in the forefront of modern science: I am especially fond of the "Black Sun," which is an obvious description of the now extremely popular Black Holes.

I will say no more about Greg's version—or my own. I'll leave you to enjoy both.

One other aside, though. By a strange coincidence, while almost simultaneously we had the proposal to write the sequel to Against the Fall of Night, the excellent Australian science fiction writer Damien Broderick ("The Dreaming Dragons") wrote asking if he could write a sequel to The City and the Stars ! In view of Greg's project, I reluctantly turned it down—but perhaps in another decade. . . .

Arthur C. Clarke Colombo, Sri Lanka May 29, 1989

P R O L O G U E

Not once in a generation did the voice of the city change as it was changing now. Day and night, age after age, it had never faltered. To myriads of men it had been the first and the last sound they had ever heard. It was part of the city: when it ceased the city would be dead and the desert sands would be settling in the great streets of Diaspar.

Even here, half a mile above the ground, the sudden hush brought Convar out to the balcony. Far below, the moving ways were still sweeping between the great buildings, but now they were thronged with silent crowds. Something had drawn the languid people of the city from their homes: in their thousands they were drifting slowly between the cliffs of colored metal. And then Convar saw that all those myriads of faces were turned toward the sky.

For a moment fear crept into his soul—fear lest after all these ages the Invaders had come again to Earth. Then he too was staring at the sky, entranced by a wonder he had never hoped to see again. He watched for many minutes before he went to fetch his infant son.

The child Alvin was frightened at first. The soaring spires of the city, the moving specks two thousand feet below—these were part of his world, but the thing in the sky was beyond all his experience. It was larger than any of the city's buildings, and its whiteness was so dazzling that it hurt the eye. Though it seemed to be solid, the restless winds were changing its outlines even as he watched.

Once, Alvin knew, the skies of Earth had been filled with strange shapes. Out of space the great ships had come, bearing unknown treasures, to berth at the Port of Diaspar. But that was half a billio

n years ago: before the beginning of history the Port had been buried by the drifting sand.

Convar's voice was sad when presently he spoke to his son.

"Look at it well, Alvin," he said. "It may be the last the world will ever know. I have only seen one other in all my life, and once they filled the skies of Earth."

They watched in silence, and with them all the thousands in the streets and towers of Diaspar, until the last cloud slowly faded from sight, sucked dry by the hot, parched air of the unending deserts.

The lesson was finished. The drowsy whisper of the hypnone rose suddenly in pitch and ceased abruptly on a thrice repeated note of command. Then the machine blurred and vanished, but still Alvin sat staring into nothingness while his mind slipped back through the ages to meet reality again.

Jeserac was the first to speak: his voice was worried and a little uncertain.

"Those are the oldest records in the world, Alvin—the only ones that show Earth as it was before the Invaders came. Very few people indeed have ever seen them."

Slowly the boy turned toward his tutor. There was something in his eyes that worried the old man, and once again Jeserac regretted his action. He began to talk quickly, as if trying to set his own conscience at ease.

"You know that we never talk about the ancient times, and I only showed you those records because you were so anxious to see them. Don't let them upset you: as long as we're happy, does it matter how much of the world we occupy? The people you have been watching had more space, but they were less contented than we."

Was that true? Alvin wondered. He thought once more of the desert lapping around the island that was Diaspar, and his mind returned to the world that Earth had been. He saw again the endless leagues of blue water, greater than the land itself, rolling their waves against golden shores. His ears were still ringing with the boom of breakers stilled these thousand million years. And he remembered the forests and prairies, and the strange beasts that had once shared the world with Man.

All this was gone. Of the oceans, nothing remained but the gray deserts of salt, the winding sheets of Earth. Salt and sand, from Pole to Pole, with only the lights of Diaspar burning in the wilderness that must one day overwhelm them.

And these were the least of the things that Man had lost, for above the desolation the forgotten stars were shining still.

"Jeserac," said Alvin at last, "once I went to the Tower of Loranne. No one lives there anymore, and I could look out over the desert. It was dark, and I couldn't see the ground, but the sky was full of colored lights. I watched them for a long time, but they never moved. So presently I came away. Those were the stars, weren't they?"

Jeserac was alarmed. Exactly how Alvin had got to the Tower of Loranne was a matter for further investigation. The boy's interests were becoming—dangerous.

"Those were the stars," he answered briefly. "What of them?"

"We used to visit them once, didn't we?"

A long pause. Then, "Yes."

"Why did we stop? What were the invaders?"

Jeserac rose to his feet. His answer echoed back through all the teachers the world had ever known.

"That's enough for one day, Alvin. Later, when you are older, I'll tell you more—but not now. You already know too much."

1

Alvin never asked the question again: later, he had no need, for the answer was clear. And there was so much in Diaspar to beguile the mind that for months he could forget that strange yearning he alone seemed to feel.

Diaspar was a world in itself. Here Man had gathered all his treasures, everything that had been saved from the ruin of the past. All the cities that had ever been had given something to Diaspar: even before the coming of the Invaders its name had been known on the worlds that Man had lost.

Into the building of Diaspar had gone all the skill, all the artistry of the Golden Ages. When the great days were coming to an end, men of genius had remolded the city and given it the machines that made it immortal. Whatever might be forgotten, Diaspar would live and bear the descendants of Man safely down the stream of Time.

They were, perhaps, as contented as any race the world had known, and after their fashion they were happy. They spent their long lives amid beauty that had never been surpassed, for the labor of millions of centuries had been dedicated to the glory of Diaspar.

This was Alvin's world, a world which for ages had been sinking into a gracious decadence. Of this Alvin was still unconscious, for the present was so full of wonder that it was easy to forget the past. There was so much to do, so much to learn before the long centuries of his youth ebbed away.

Music had been the first of the arts to attract him, and for a while he had experimented with many instruments. But this most ancient of all arts was now so complex that it might take a thousand years for him to master all its secrets, and in the end he abandoned his ambitions. He could listen, but he could never create.

For a long time the thought-converter gave him great delight. On its screen he shaped endless patterns of form and color, usually copies—deliberate or otherwise—of the ancient masters. More and more frequently he found himself creating dream landscapes from the vanished Dawn World, and often his thoughts turned wistfully to the records that Jeserac had shown him. So the smoldering flame of his discontent burned slowly toward the level of consciousness, though as yet he was scarcely worried by the vague restlessness he often felt.

But through the months and the years, that restlessness was growing. Once Alvin had been content to share the pleasures and interests of Diaspar, but now he knew that they were not sufficient. His horizons were expanding, and the knowledge that all his life must be bounded by the walls of the city was becoming intolerable to him.

Yet he knew well enough that there was no alternative, for the wastes of the desert covered all the world.

He had seen the desert only a few times in his life, but he knew no one else who had ever seen it at all. His people's fear of the outer world was something he could not understand: to him it held no terror, but only mystery. When he was weary of Diaspar, it called to him as it was calling now.

The moving ways were glittering with life and color as the people of the city went about their affairs. They smiled at Alvin as he worked his way to the central high-speed action. Sometimes they greeted him by name: once it had been flattering to think that he was known to the whole of Diaspar, but now it gave him little pleasure.

In minutes the express channel had swept him away from the crowded heart of the city, and there were few people in sight when it came to a smooth halt against a long platform of brightly colored marble. The moving ways were so much a part of his life that Alvin had never imagined any other form of transport. An engineer of the ancient world would have gone slowly mad trying to understand how a solid roadway could be fixed at both ends while its center traveled at a hundred miles an hour. One day Alvin might be puzzled too, but for the present he accepted his environment as uncritically as all the other citizens of Diaspar.

This area of the city was almost deserted. Although the population of Diaspar had not altered for millennia, it was the custom for families to move at frequent intervals. One day the tide of life would sweep this way again, but the great towers had been lonely now for a hundred thousand years.

The marble platform ended against a wall pierced with brilliantly lighted tunnels. Alvin selected one without hesitation and stepped into it. The peristaltic field seized him at once, and propelled him forward while he lay back luxuriously, watching his surroundings.

It no longer seemed possible that he was in a tunnel far underground, the art that had used all Diaspar for its canvas had been busy here, and above Alvin the skies seemed open to the winds of heaven. All around were the spires of the city, gleaming in the sunlight. It was not the city as he knew it, but the Diaspar of a much earlier age. Although most of the great buildings were familiar, there were subtle differences that added to the interest of the scene. Alvin wished he could li

nger, but he had never found any way of retarding his progress through the tunnel.

All too soon he was gently set down in a large elliptical chamber, completely surrounded by windows. Through these he could catch tantalizing glimpses of gardens ablaze with brilliant flowers. There were gardens still in Diaspar, but these had existed only in the mind of the artist who conceived them. Certainly there were no such flowers as these in the world today.

Alvin stepped through one of the windows—and the illusion was shattered. He was in a circular passageway curving steeply upward. Beneath his feet the floor began to creep slowly forward, as if eager to lead him to his goal. He walked a few paces until his speed was so great that further effort would be wasted.

The corridor still inclined upward, and in a few hundred feet had curved through a complete right angle. But only logic knew this: to the senses it was now as if one were being hurried along an absolutely level corridor. The fact that he was in reality traveling up a vertical shaft thousands of feet deep gave Alvin no sense of insecurity, for a failure of the polarizing field was unthinkable.

Presently the corridor began to slope "downward" again until once more it had turned through a right angle. The movement of the floor slowed imperceptibly until it came to rest at the end of a long hall lined with mirrors. Alvin was now, he knew, almost at the summit of the Tower of Loranne.

He lingered for a while in the hall of mirrors, for it had a fascination that was unique. There was nothing like it, as far as Alvin knew, in the rest of Diaspar. Through some whim of the artist, only a few of the mirrors reflected the scene as it really was—and even those, Alvin was convinced, were constantly changing their position. The rest certainly reflected something, but it was faintly disconcerting to see oneself walking amid ever-changing and quite imaginary surroundings. Alvin wondered what he would do if he saw anyone else approaching him in the mirror-world, but so far the situation had never arisen.