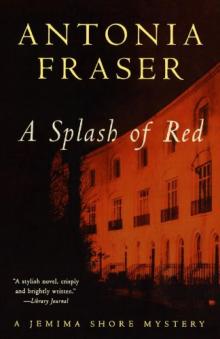

A Splash of Red

Antonia Fraser

A Splash of Red

Antonia Fraser

Author's Note

Adelaide Square, either designed by Adam or ruined by Sir Richard Lionnel, does not exist. For the purposes of this story, I have placed it to the West of the British Museum, sandwiched between Bedford Square and Tottenham Court Road.

Contents

'No noise'305

Disappearing in London 316

'Care for a visit?'325

Irish accent335

The Lion's Den343

B for Beware352

Scheherazade361

Who, Who?371

Fallen Child381

A carnal encounter391

Curiouser and curiouscr 400

Shattered410

Strong women419

Back to Athens430

A white petticoat438

Straw into gold448

Lovers in disguise460

The fatal Saturday468

'Tell me who to kill'478

The last word488

For Damian and other family voices heard at Praia de Luz

1

'No noise'

'At least you'll be very quiet up here,' said Chloe. 'All on your own. Except for Tiger, of course. And in his own way he's very quiet too.'

'Like all cats. Part of what I love about them. The silent comings and goings.' Jemima Shore spoke comfortingly, and gave a long hard rub to Tiger's back as she did so. Tiger arched and his tail went up; he was not to be won so easily. Jemima stopped and Tiger shot away. His departure was soundless on the thick beige furry carpet which covered Chloe Fontaine's flat.

'All the same, you're sure you won't be lonely?' Chloe asked anxiously, putting down her mug of coffee on the wide glass table. The mug was the colour of oatmeal, like most of the furnishings in the flat; the milky coffee blended with the other subdued colours. Even Tiger, a long-haired golden cat, fitted in with the decor - or perhaps, reflected Jemima, it had been chosen round him. Everything in the flat was not only very light but also very clean. Of course Chloe had only just moved in; nevertheless Jemima knew from previous experience of Chloe's houses and flats that the cleanliness was something spiritual in her - a protest of the soul, she sometimes felt, against the disorder of her private life. Mind against Body.

Meanwhile Chloe was looking round her, still anxious, as though, unexpectedly, the flat might reveal some hidden source of either noise or comfort - it was not quite clear which.

'I want to be lonely,' thought Jemima Shore. 'That's why I'm here. Pure selfishness. Not really to help you out at all.' Aloud she said in the kind of bracing voice she had been using to Chloe since they were at Cambridge together: 'I'm never lonely, Clo. You know me. I shall love it here. It's so tranquil. And looking after Tiger will cheer me up.'

Jemima's beautiful and beloved tabby Colette had had to be put down six weeks earlier. Jemima still found the return to her own flat, now empty, intolerable. It was one of the reasons she was happy to move away from it for the time being. 'It's so tranquil here,' she repeated.

As she spoke, Jemima Shore's eye was caught by a splash of colour through the open door of the pale bedroom. For a moment it looked as if red paint - or even blood - had been dashed on the wall. Then she realized that she was looking at an enormous canvas slurred with red. A woman's figure was involved. The picture gave Jemima a momentary sense of discomfort, the first since she had entered Chloe's cloistered off-white apartment.

Chloe followed the direction of her eyes and smiled.

'You're surprised to see it?'

'Well, everything else is so—'

'I decided to keep just one. And that was the right one to keep. The most violent one of all. To remind me. Never ever again. "A Splash of Red". No, that's its title. No matter how many calls, how many evening threats, midnight pleas, how many early-morning demands... 'Jemima realized that the red-splashed picture was by Chloe's lover - or rather her former lover - Kevin John Athlone. This fact did not make her feel any warmer towards the picture. Besides, Chloe's reason for hanging it was not totally convincing, in view of her famous fastidiousness. Jemima wondered, rather wearily, whether somewhere in her soft heart, Chloe was still in love with the appalling Kevin John.

Yet Chloe's whole reason for leaving her pretty little house in Fulham to live in this new block of history-less flats in Bloomsbury had been as she phrased it tearfully on the telephone 'to put the past behind me. I've had it, Jem, absolutely had it. I can't stand it any more, the noise, the shouting, the rows, the blows - yes, of course there were blows, can't you see it just by looking at him? - no of course I didn't call the police, Jemima, no point, in any case the noise of it was almost worse than the blows. Anyway I'm just off, off to a new flat, just Tiger and me, somewhere where there's no Kevin John and above all No Noise.' This conversation had ended on a note of rising hysteria.

Chloe Fontaine's new flat was in a large Georgian square near the British Museum. It was certainly an extremely quiet area. Most of the other houses contained offices; but they were offices belonging to solicitors, architects, publishers and other sober professional people. During the day the bustle of business was subdued and scarcely likely to disturb. Even nearby Tottenham Court Road provided little more than a dull reverberation. At night, Chloe told Jemima, there was really nothing to be heard at all. The flats below Chloe's were still empty.

'At least he doesn't have your address. Or I very much hope not!' exclaimed Jemima, stretching out her long legs, tanned from the hot summer, across the carpet. Happily they toned with it. Unlike the picture.

'No, of course he doesn't,' Chloe said quickly. 'I believe he's gone back to Cornwall, to that studio he used to have. And he's living with a Vietnamese girl. Vietnamese? No, probably not. Balinese? Siamese? Something oriental and' - a pause - 'no doubt submissive.' There was a small silence.

'Listen,' Chloe went on in a much brisker voice. 'I've always liked that picture. For itself alone, believe it or not. I think I was rather exaggerating its significance in my life. Now the main point is, will you be lonely? I'm sorry about Rosina packing up, by the way, although you may not be. Rosina is a good sort but she's a compulsive talker. In the six weeks since I moved here most of my work has been done in a vain attempt to ward off her conversation. She said she'd be away about a fortnight - but she's not a very accurate prophet about her own movements; I suppose she has to be back before I am. Depends on the wretched child's progress. How long do you take to recover from tonsils, darling? Little Enrico is not even a good sort like his mother but he has inherited the art of conversation from her, so whatever you do -for your own peace, don't let her bring him.'

'As usual it's all immaculate,' began Jemima. 'There would be nothing for Rosina to do.'

But Chloe was rattling on, and jangling some keys at the same time. 'One thing, whatever you do don't forget your keys. The separate flat buzzers which open the front door aren't ready yet, so it's left open in the day, locked in the evening. And there really is no one within earshot at night. Believe it or not, I did that last week - forgot my keys - and had to spend the night out in Adelaide Square, after climbing over the railings. I know it's a fabulous summer. Even so - but what could I do?'

Chloe sighed, laughed, and continued. 'Still it was an interesting experience in its own way. Rather a surprise altogether. Might have altered the course of my life if I didn't already have a new angel, the most divine angel in heaven. As it was, it was just a little, a very little, adventure. A casual encounter you might say. A carnal encounter, perhaps. Rather naughty of me under the circumstances. But I couldn't resist it.'

Jemima felt relieved. All was explained, including the slightly frenetic quality in Chloe's conversation. A new lover. No

t an old fear. No, this was not at all the distraught neurotic Chloe of months back, but the mercurial creature whose changing romances were the wonder of her friends. Like the ordered decor of her houses, Chloe's fragile appearance was belied by the tempestuous nature of her private life. Since Cambridge, when Jemima Shore had been drawn to Chloe's delicate Marie Laurencin looks - sloe eyes in a pale child's face - she had wondered at this contradiction.

What was more, no hint of it appeared in Chloe's work. In her writing Chloe was the reverse of tempestuous: on the contrary, she gave the impression of one wittily in command both of herself and her characters.

'Even Tiger's life is not as crammed with incident as Chloe's,' Guthrie Carlyle had once remarked rather crossly to Jemima. 'And he's a torn cat. What's more, Tiger is a lot more discreet. Is it possible that Chloe's cat actually wrote Fallen Child-, do you suppose? When I think of that exquisitely honed prose and those finely judged characters, and then this latest scrape of Chloe's...' They were discussing Chloe's decision to leave her husband for Kevin John Athlone at the time - 'I know it only adds to the fascination,' he added hastily.

Guthrie Carlyle was Jemima's devoted assistant at Megalith Television. He had once been more than that - Jemima's devoted lover, but the affair had come to an end after Jemima's involvement in certain events, both passionate and strange, in Scotland. The tragic outcome of it all had killed in Jemima any desire for anything except work - work and oblivion. Guthrie had accepted this tacit dismissal from one of his two roles in Jemima's life with that air of whimsical sadness which he used to cover up his deepest feelings; however, Guthrie and Jemima remained close friends as well as colleagues.

Jemima Shore was the writer and presenter of one of the more popular serious television programmes. She was billed as Jemima Shore, Investigator, and the title had appealed to the popular imagination as though she were some kind of amateur detective. In fact the title was merely a catchphrase and the kind of thing Jemima investigated on television was more likely to be slum housing or the fate of unmarried mothers or some combination of the two with perhaps the medical risks of the Pill thrown in for good measure. Nevertheless the title had caught on in the minds of the public and in recent years a number of people had appealed to Jemima Shore to solve their problems - with success. Curiosity was a habit of mind to her. It was tempting even now to try and work out the identity of Chloe's lovers by considering the clues. But she must restrain herself. She had a purpose in coming to Bloomsbury. Distractions were to be avoided.

She concentrated on Chloe's future plans.

'Do I take it then that you're not after all going on this famous holiday alone?' she asked. 'I'd rather imagined that since Kevin John there hadn't been anyone, well, serious...'

'Oh, darling, it's absolutely not a holiday, not in that sense.' Chloe was busy scribbling down a list of local shops ('I advise plunging down into Soho for anything decent: cross Tottenham Court Road, down the Charing Cross Road, avoid the dirty bookshops and it's nearer than you think'). 'No darling, I would hardly ask you to come over here, all of a sudden, just like that,' she continued, 'if I was off on a spree. No, it's work, and God knows I need it. Do you know that my last book sold exactly four thousand copies, in spite of Valentine's gallantly pornographic jacket. And Jamie Grand's angelic review; no, not him personally - though he is an angel - but his deeply pompous and deeply powerful paper. So loyal to give it to Marigold Milton, who absolutely adores my work, when you think what some of his other lovely ladies might have made of it.'

Jemima recalled the jacket of Fallen Child and shuddered: some kind of naked bathing scene had been depicted, a sort of dejeuner sur l'herbe including all the family. It crossed her mind that Valentine Brighton was not to blame, and that the artist had not penetrated Chloe's elegant prose beyond the first twenty-five pages ... still, as publisher, Valentine should have known better. Or perhaps he did and considered the end (sales) justified the jacket.

Jemima murmured sympathetically but without committal on the subject of the jacket. She herself felt on strong ground on the subject of Chloe's work since she genuinely admired it, and had done so since Chloe's first novel was published shortly after they both left Cambridge. She liked the mixture of precision and sensibility; the particular sly humour which regularly inspired critics to compare Chloe to Jane Austen. They generally added: 'And I do not use the comparison lightly.' To which Chloe would regularly respond: 'No, they undoubtedly use it very heavily.' But Jemima suspected that in her heart of hearts Chloe was not quite so displeased.

Comparisons to contemporary female writers, however distinguished, on the other hand maddened her. 'Another Olivia Manning' was one comment which had provided weeks of irritation; nor was Chloe more satisfied when reviewers in the United States mentioned the name of the ironic and brilliant Alison Lurie, and suggested that the latter had provided an inspiration.

'Anyway I found the round figure highly suspicious,' Chloe was rattling on in her attractive breathless voice, an attribute which underlined further the childlike quality of her appearance. 'And I told Valentine as much, but he swore, in that utterly convincing honour-of-the-regiment way of his which always makes one even more suspicious - he swore it was exactly four thousand. In the meantime I'm in a load of trouble over my new book - believe it or not, libel, quite ridiculous how sensitive people are, of course there's nothing in it - but he, Valentine that is, is hanging on to the advance. He says the best he can do to tide me over is to pay me a flat sum if I edit an anthology of women's letters down the ages. The Quiet Art - no, not heart, art, don't laugh, I know it's pretty desperate, but I'm trying to make something of it. Even I have been investigating the Reading Room of the British Library in my own quiet and, we hope, artful way ... However, as usual I need more.

'So this is good old Taffeta in the ample shape of Isabelle Mancini, commissioning me. Taffeta Schmaffeta. But at least it never lets you down. Off to France. I think Isabelle has in mind rippling tensions between a woman and a horse, with her usual optimism, whereas I see it as a lonely woman rides in Camargue. Pictures by Snowdon if we're lucky, the insufferable Binnie Rapallo if we're not. "Thoughts suggested by white chargers," cried Isabelle: she never learns. And she always adds: "Do something about the food, darling, don't forget." It's a hangover from her days as a cookery writer. What do horses eat in the Camargue? If I found out, would that satisfy her? Still, I'm going ahead for ten days to sit alone and perhaps wander and get new ideas. The photographer - Binnie, I have no doubt - follows.'

'Alone, Clo?' Jemima jumped up to pace round the apartment.

'Absolutely alone. I am definitely not taking my new angel with me. The news of my romance, by the way, is a heavy secret till I come back. I haven't broken it to the last angel, who was of all things - well, perhaps that had better be a secret too till I get back. Why give you a quick blurb on my life when a full-length novel is so much more fun? It might spoil it. A married man - no more for the present.'

Chloe was certainly right back in her old form. Two new men at least in her life - or rather new to Jemima's list of Chloe's involvements -two new men and something catalogued as an adventure. Jemima could not quite resist running through a few possible names in her head. Then she was distracted by the majestic view from the vast picture window which ran the length of the room.

Jemima could see across the tops of the great trees of Adelaide Square to the elegant eighteenth-century houses on the opposite side. Chloe's new residence was in a concrete balconied block. To Jemima's mind its style was somewhere between the Mappin Terraces at Regent's Park Zoo and the National Theatre, less charming than the former, more appealing than the latter. Its position turned its architecture into an affront.

It also seemed peculiarly unfair that the occupant of this horror would have the advantage of looking at its beautiful neighbours, whereas they in turn had to contemplate the monstrosity. Unfair indeed - she suddenly remembered the furious protests at the building of the new land

mark, or rather the demolition of the great house which had preceded it. Very understandable, but somehow the protests had either been got round or muffled.

That was, perhaps, because Sir Richard Lionnel was involved: an exotic saturnine gentleman whose tweeded figure - he did not affect the normal dark suit of a tycoon - was to be glimpsed in as many government corridors as boardrooms.

'So I shall be quite out of touch and alone, as lonely as you will be here, in a different way. No angel and no telephone calls,' Chloe was saying.

'What happened to those protesters, Clo?' Jemima interrupted. 'I'm looking into Adelaide Square. The ones who threatened this building -it was this one, wasn't it? I do see their point - if it doesn't sound ungrateful, living in your luxurious eyrie.'

'Oh, I believe the original house was riddled with dry rot, in a terrible state. I know for a fact that squatters and what-have-you were imminent. No way it could have been preserved. The facade perhaps -but that would have cost the earth.'

'So the protest just died down?'

'Oddly enough it hasn't quite. I meant to warn you, except that it's not very serious and certainly won't bother you at night. They still feel strongly about Lionnel himself. That's because they're frightened he'll do the same thing elsewhere. Notably next door. You saw the scaffolding? That battle's lost but you know what demonstrators are. You may get the odd rude note downstairs, but it will just be addressed "The Occupant", so pay no attention. There are sometimes people with placards - "The Lion of Bloomsbury, seeking whom he may devour". "Don't let the Lion eat Bloomsbury", that sort of thing. I see them there most days. But they won't bother you. Some of them are quite attractive, if you like that sort of thing. Long hair, beards and very narrow hips, if you know what I mean.' Jemima did. It was not an attraction she had ever felt. Involuntarily she frowned.