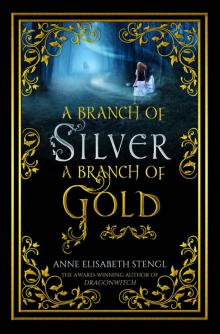

A Branch of Silver, a Branch of Gold

Anne Elisabeth Stengl

TALES OF GOLDSTONE WOOD

Heartless

Veiled Rose

Moonblood

Starflower

Dragonwitch

Shadow Hand

Golden Daughter

NOVELLAS OF GOLDSTONE WOOD

Goddess Tithe

Draven’s Light

© 2016 by Anne Elisabeth Stengl

Published by Rooglewood Press

www.RooglewoodPress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

This volume contains works of fiction. Names, characters, incidents, and dialogues are products of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Book design and cover illustration by A.E. de Silva

Stock image by iardacil-stock

CLICK TO SIGN UP

This story is for Mummy.

But really all of them are for Mummy, whether or not the dedication officially says so.

Because not a single one of my stories would be the best it could be without her.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Beginning

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

About the Author

Before there can be a beginning, there must first be an end. Otherwise, what is there to begin?

This truth I have learned in pain. This truth I have learned in suffering. This truth I have learned in gladness, for O! What sweet relief it is to my spirit! Though I am bound, I know that my binding will last only until the end. And then . . . and then . . .

But in the meanwhile, what a long ending it seems to me.

See now the worlds beyond my lonely window. Great worlds in which I once walked. Lovely worlds in which I will never walk again. See now the Between which separates those worlds, both the Near and the Far. The Far is always much nearer than mortals suppose. And, likewise, the Near much farther than Faerie-kind will admit. But as I sit here in my window, I feel it all so close to me. I gaze out through the slit in the stone wall, and I see the mortals rising to greet the new day. I turn where I sit and see the tall trees surrounding me on all sides, and moonlight bathes the forest floor at my feet.

Near and Far. Night and Day.

And in Between, the Wood stands tall.

There are figures moving through the Between. I see a shadow stalking. I see a wind spirit blowing. I see a curse shimmering, opening wide the gates.

And so Faerie-kind will once more cross over the boundaries to prey upon the mortal world. So it must be.

So it must end.

ONE

The words would not stay put. He had just written them, so he knew exactly what they should say. But they wouldn’t say it. At least, not in a way he could understand. They swam in weird undulations across the page, incomprehensible as a child’s scribblings. The more he studied them, the stupider he felt.

Master Benedict Cœur, son and heir of the Marquis of Canneberges, sat at his desk, his head in his hands, and felt profoundly sorry for himself. His eyes blurred with fatigue, and he should probably go back to bed. But this thought made him shudder. He’d spent all night in that bed, staring up at his canopy, unable to sleep save in stolen snatches. The moment the sky began to lighten, he’d crawled out from under the counterpane, lit a candle, and pulled out his documents. Anything to fill his mind, anything to block out the crowd of thoughts that had kept him company through the long hours of darkness.

Only now . . .

He groaned and closed his eyes, his head still propped and bent. Cold morning air blew through his open window, and he wished he dared shut the glass and stoke up his fire. But Doctor Dupont would be furious at such blatant disregard of his apothecarial commands. And Benedict lacked sufficient energy to face the good doctor’s fury this morning.

If only he dared steal a horse. Probably a foolish notion, but he rather liked it anyway. Technically it wouldn’t be stealing, since he was heir to his father’s estate and, therefore, practically owned all the horses and the stables and . . . well, everything. Legally, of course, it all belonged to his father. The marquis wasn’t home, however, so who would gainsay his heir? But Doctor Dupont was officially in charge during Monsieur the Marquis’s absence, and Doctor Dupont had strictly ordered the stable hands to allow Benedict nowhere near a horse.

But the stable hands weren’t the brightest lights in the county. And it would be an adventure, just the sort of adventure Benedict would have pursued only a year ago: Steal a horse right out from under the grooms’ noses, then up in the saddle, away across the fields, and dragons eat all scholarly pursuits!

Victor would have told him to do it. Benedict could almost hear his best mate urging him even now: “You’ve got all your life to worry about memorizing Corrilondian conjugations and declensions. But today will be over before you know it!”

“Today will be over before you know it,” the young scholar whispered. How true those words had become to him these last long months. He shook his head, shook away the memory of that voice, and tried once more to concentrate on the difficult lines of Corrilondian verbs and nouns. Learning a foreign language was difficult enough without the words swimming around on the page like so many—

BANG.

Benedict startled upright in his chair and sat like a hare frozen at the sound of a hunter’s bolt whizzing past.

BANG.

BANG. BANG.

BANGBANGBANGBANG.

Had a hurricane entered the house somehow? Right over his head, in the Great Hall above?

Eyes wide, mouth gaping, Benedict stared up at his ceiling as though he could somehow see through it and discover the cause of the uproar.

Another great BANG, and something roared down his chimney and burst into his room. Something invisible, something strong. Something most certainly alive.

It blew out the fire, then roared across the chamber to his bed and tossed the blankets awry, whirled around the four bedposts, and made the canopy and curtains balloon like sails on the high seas. It tore around the periphery of the room, knocking bo

oks and ledgers from their places, then caught up all the work upon Benedict’s desk and spun it into a swirling white storm.

Benedict shouted but couldn’t hear his own voice over the howl of the wind and what he recognized suddenly as high, wild, insane laughter. Never in his life had he heard a voice utter such inhuman sounds. He flung up his arms to protect himself from papercuts and flying penknives.

Then, as though seeing it suddenly, the wind—given something close to a physical form by virtue of all the papers clutched in its invisible arms—darted for the open window and flung the casement wide open to crash against the outer wall. The laugh trailed away across the moat and into the morning-lit fields beyond Centrecœur House.

Benedict stood in the middle of his chamber and stared at the destruction around him, at all his hard work strewn, scattered, or stolen.

“Dragon’s eyeteeth,” he cursed.

Then, catching up his hat and cloak, forgetting his fatigue, he rushed from the room. If ever there was a time to steal a horse and give chase, that time was now.

Somewhere out there is someone who can hear me. I know this must be true. I sensed it hours ago, before the sun crested the horizon. I felt it at the turning of Yesterday into Today, at that dark and most magical moment of Midnight. Yesterday she could not hear me. But today . . . today I believe she can.

So I sit at my window and watch the sun spill across the fields, forests, and bogs of this mortal land where once I walked. And I send forth my heart, crying out to her.

This time. Maybe this time.

I do not wonder whether or not she’ll hear me. I wonder whether or not she’ll answer.

TWO

On the morning of her fourteenth birthday, just as the sun rose and Rufus the Red, the family rooster, raised his voice in raucous welcome of the new day, Heloise opened her eyes, stared at the thatching just overhead, and thought: Mirror.

It wasn’t really a thought. At least, it wasn’t like any thought she had experienced before. It was more like an impression. Or a suggestion. Lying there in the pile of straw that was her bed, wrapped tightly in a woolen blanket, she whispered softly, so as to make no sound but so that her breath formed little curls in the air above her lips, “What mirror?”

A foolish question. There was only one mirror. Oh, she knew as a distant sort of truth that other mirrors existed. She knew this just as she knew there was a world beyond Monsieur de Cœur’s estate of Canneberges. It may be true, but she never expected to see it, so it didn’t particularly matter. The same held true when it came to mirrors. As far as her immediate world was concerned, the only mirror that mattered was her mother’s small glass.

Mirror.

There it was again. That word tugging at the ear of her consciousness. Heloise’s frown deepened.

Her name was Heloise Flaxman, though when she was younger she’d thought it ought to be Flaxgirl, which would make more sense. A few years ago she’d asked her older sister, Evette, about the incongruity of her name. Evette had told her that “Flaxman” let everyone know Heloise was the daughter of one of the many flax farmers on the estate. The name gave her a place. It gave her standing.

Heloise, only nine years old at the time, had gone about her daily tasks, her brow knitted in serious contemplation of this new knowledge. Later that same afternoon, while she and Evette fed Gutrund the pig, she’d asked, “Since Meme is a spinner, can’t I be Heloise Spinnerwoman? Then everyone would know I’m the daughter of a spinner. And spinning is more interesting than farming.”

“No,” said Evette. “That’s not how things are done.”

Thus ended their discussion. When it came to questions of “how things are done,” Evette could not be convinced to think creatively. So Heloise had resigned herself to being Heloise Flaxman for the foreseeable future.

This morning, however, when she awoke as always to the passionate crowing of Rufus the Red, she didn’t feel quite like a Heloise Flaxman anymore. She felt changed. Not older, necessarily, but . . . bigger. As though there were more of her than there had been the night before.

Sitting up and unwrapping herself from the tangle of her blanket, she cast a quick glance to the nearby pile of straw where her sister slept. But of course Evette had already risen, dressed, and had climbed down from the loft to the kitchen below, where she helped Meme get breakfast for Papa and the boys. Evette was never one to sleep late. It’s not how things were done.

Down in the main room Heloise heard the scuffle and shouts of her brothers Claude, Clement, Clotaire, and Clovis engaged in their morning brawl, accompanied by the high-pitched squeals of baby Clive goading them on. Underscoring all other noises murmured the patient voice of Evette in her accustomed role of peacekeeper. Heloise woke to this chorus every morning, but today these familiar sounds seemed strangely distant.

Mirror.

The word was in her head still. She climbed out of the straw and crawled across the loft floor to a carved cedar box tucked away in the corner. Heloise’s grandfather had made that box for her mother when her mother was a child. Its contents were as familiar to Heloise as her own two hands. She lifted the lid, breathed in the scent of cedar, and looked down at folds of creamy linen: Meme’s wedding gown.

Heloise had no interest in this whatsoever. Meme often spoke of how Evette would soon wear it in her own wedding; Evette was at an age when their mother could scarcely look at her without speaking of weddings and babies, as though Evette were already betrothed and settled. Lately she’d taken to saying on a near-daily basis, “We’ll have a wedding in the family before this spring is done; you mark my words!” To which Evette always smiled and made no reply.

Weddings and Evette—they went together like dye and mordant in Heloise’s mind. She never pictured herself in the bride role. After all, she was not Evette.

Wrapped up inside the gown, tucked away for safekeeping, was the little black-framed mirror, the prized treasure of the Flaxman household. This Heloise unwrapped from the gown with great care, leaving the mounds of linen to lie unheeded in her lap. Gently she lifted the mirror, angling it so that she could not see her face. She wasn’t afraid, exactly. Maybe a mite anxious. But not afraid. Certainly not.

Mirror, said the thought in her head.

“Yes. Yes, I know,” Heloise whispered. By now she thought she knew why the thought was there: Today was her birthday. On every birthday Heloise could remember she’d awakened wondering if she was any different than she’d been the night before, but one furtive glance in the spotted glass always showed her to be the same as ever. Maybe a little taller than she’d been a year ago. Perhaps with a few more freckles. But still very much herself.

Not this morning. This morning she knew that she was still herself . . . but something more besides.

Heloise heard Papa say goodbye to Meme, and then he and Claude and Clement, the two oldest brothers, set out for the flax fields. She heard Meme tell Evette that the south-end dye house had sent a request for more oak bark and could she please inform her sister as soon as she saw fit to rise? Then, not waiting to see her younger daughter or wish her a fortunate birthday, Meme gathered up baby Clive and left the cottage. Out to the spinning shed, where she would spend the rest of the day. At any moment Evette would call up the ladder, asking in her sweetest, most patient voice whether or not Heloise planned to join them that morning.

If she was going to look at herself, it had better be quick.

And really, what was there to worry about? A strange feeling? What did that even mean? Nothing and nonsense, certainly.

Heloise flicked the mirror upright.

The glass was warped along the top, making the viewer’s forehead look much fatter than it was. But it still gave a much better reflection than Gutrund the pig’s water trough, which was the only other place Heloise had ever seen her own face. No other farmer’s cottage in all Canneberges boasted a mirror, at least not as far as Heloise knew. It made her wonder if her batty old grandmother’s wild claims that they ca

me from “noble stock, way back when” might hold some kernel of truth, if this mirror might be the last heirloom of a highborn heritage.

Heloise gazed at her reflection. No new freckles. Well, that was something. She had not yet braided her hair for the day, and it stood out around her head in an enormous halo of fuzzy curls, giving her a wild, fey aspect which she rather liked. Her brows bunched in a tense knot, which was not unusual for Heloise, who tended to look upon the world through pensive eyes.

But was she changed?

“Heloise! Will you be joining us this morning?” Evette called from below, exactly as predicted.

“Yes, coming!” Heloise shouted back. Still she did not move. Her hands clutched the polished frame of the mirror, drawing it closer to her face until her breath fogged the glass. That was no use. Frowning harder, she caught the hem of her sleeve in her fingers and rubbed away the fog. And there was her face again, looking up at her through the spots and speckles.

Something was different. She knew it.

Mirror.

“Heloise, there’ll be no pottage left if you don’t hurry your feet.”

“Coming! Coming!” Heloise tossed the words over her shoulder and slowly lowered the glass into the pile of wedding gown, then began to fold up the soft fabric.

Her hands froze. Her frown deeper than ever, she leaned down close to the glass, pulling back the linen once more.

Slowly, with extreme deliberation, as though determined that she wouldn’t miss it . . . her reflection winked at her.

“I saved some for you,” Evette said, holding up a bowl of salvaged pottage. “It’s gone cold, but you’d better eat it anyway.”

Heloise, her hair still wild about her face, jumped the last three rungs of the ladder and landed with a thud in the floor rushes. Ignoring Evette’s exclamations that now she’d have to sweep the rushes flat again, Heloise took the proffered bowl and squeezed onto the hearth bench between brothers Clotaire and Clovis who, having called a truce, were finishing their own breakfasts. She rolled a piece of stale flatbread into a spoon and shoveled a glob of pottage into her mouth. It was clotted and cold. She swallowed without noticing.