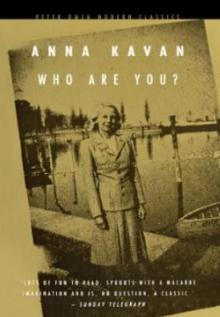

Who Are You?

Anna Kavan

1

All day long, in the tamarinds behind the house, a tropical bird keeps repeating its monotonous cry, which consists of the same three inquiring notes. Who-are-you ? Who-are-you ? Who-are-you ? Loud, flat, harsh and piercing, the repetitive cry bores its way through the ear-drums with the exasperating persistence of a machine that can't be switched off.

An identical cry echoes it from further away, calling out the same unanswered question, which is transmitted to other birds of the same species, until hundreds or thousands of them are shouting it all together. The ceaseless cries come from all distances and directions, from everywhere at once. Some are louder than others, or more prolonged; but all have the same infuriating mechanical sound, and seem devoid of feeling - they don't express fear, love, aggression, or anything else - as if uttered simply to madden the hearer. The intolerable thing about them is the suggestion that they are produced by machines nobody can stop, which will eternally repeat the question no one ever answers.

As probably they do in another dimension, to which the listener may be conveyed in delirium . . . until the ultimate nightmare climax . . . when suddenly everything stops . . .

2

The tamarind trees, old and huge, neither quite in nor quite out of leaf, tower over the house, creating a tantalizing illusion of shade, in this burning climate. But their sparse foliage and thin twisting branches cast only a confused net of shadow that gives no relief from the sun. The giant trees seem to exist principally as perches for the many brain-fever birds which, ever since dawn, have been hammering out their perpetual unanswered question.

Now the sun is low in the sky. Its dazzle catches the tops of the trees, which merge indistinguishably into one another, the birds invisible in the glare, among the tangle of spidery branches. All one sees is the tremendous size of the tamarinds, the web-like intricacy of their interlaced boughs, speckled with small, dry-looking leaves of no special colour.

Though built only a few years ago, the house below has already been touched by the galloping decay of the tropics, and is infested by rats and termites. Brick below, the upper storey stained wood, it looks vaguely neglected, and seems to crouch, beaten down by the heat, having been constructed without regard for coolness, its insubstantial walls cracking, its woodwork warped and bleached by the sun. A few banana trees grow almost touching the walls, and tufts of their long, narrow leaves poke through the glassless windows, when these are not covered by metal fly-screens or wooden shutters, several of which are defective, so that they hang crooked.

In the middle of the house a square porch shades the front door and the car standing there, its flat roof railed round as if it were meant for a sitting-out place, though, facing straight into the sun, it is useless for this purpose during the day. It overlooks, and is in full view of, the road, a dirt track with two deep parallel ruts worn by the wheels of the bullock carts which compose most of its traffic.

The bare, brownish compound dividing the house from the road is intended to be a garden, though nothing grows there but a single tall dilapidated palm tree in the middle. Its topmost leaves wave vigorously, with a clattering, almost metallic sound in occasional gusts of hot wind; but the dead lower leaves, which should have been removed, hang down in an untidy, decaying mass round the trunk. Beyond the road stretches a disorderly terrain, confusing to the eye, which retains no clear impression of it. Here the plain meets stony, scrub-covered hills, invaded by spearheads of jungle, spreading down from higher hills in the background. A group of great forest trees, entangled in creepers as thick as an arm, creates a sudden black area of shade on the right of the house, but unfortunately this doesn't reach anywhere near it. To the left is a swamp, full of snakes and leeches, covered by the large, bright green platters of fleshy plants growing in the treacherous mud these leaves conceal.

As the sun sets, colour drains visibly from the sky, against which the treetops behind the house, freed from dazzle, suddenly stand out clearly in all their intricate complexity. It should now be possible to see the brain fever birds, which at last are silent. However, they remain invisible, either because their immobility makes them indistinguishable from the involved pattern of the branches, or because they've already flown off to different roosting places.

Far more striking than their non-appearance, is the abrupt cessation of their nerve-racking cries. The eternal, monotonous question without an answer has woven itself into the whole fabric of the day, and even now still leaves behind it a soundless echo, like some obscure irritant of the mind.

3

Daylight vanishes in six minutes flat, leaving only a faint violet smear marking the western sky. Stars flash out one after the other. In the swamp, frogs have begun making a great noise, which steadily grows louder, an incessant chorus of croaking, gulping and barking sounds working up periodically to a climax, when it is called to order by the punctuation point of a startlingly deep, gruff, batrachian boom, louder than all the rest, after which the cycle builds up again.

The moon has not yet risen. Only a faint ghostly sheen of starlight hovers over the marsh. The house is to be heard rather than seen, its timbers emitting cracks like pistol shots as the air cools and the faulty structure contracts and subsides. A thin penciling of horizontal light-lines marks the position of windows. Two, longer than the others, open on to the flat roof of the porch, and through these a young girl emerges, advancing towards the rails — they cut her off at the knee seen from below, as she leans upon them. The light from inside the house isn't bright enough to show the colour of her dress, which is probably white.

She raises both hands and lifts her hair for a moment to cool her neck, then lets it fall and again leans on the rail. She is quite motionless, leaning forward slightly as if trying to see something on the ground below; which is impossible, the darkness being impenetrable down there. Her hair, no darker than her dress, hangs almost shoulder length in a long, childish bob, unskillfully imitating the style known as 'page boy'.

The racket the frogs are making doesn't drown the exasperating cry of the brain-fever bird, which has crept right into her head. Divorced from its cause, this lingering irritation is able to attach itself to anything in the dark, where nothing is distinguishable from anything else. She associates it in turn with the heat, the frogs, and then with the jingle and flickering gleam which would be the sole evidence of a passing bullock cart, if the driver did not keep up a loud chanting to protect himself from the demons of the swamp.

The girl never moves an inch; does not look round when a dignified barefooted servant, with a white turban and a grey beard, comes to the window behind her. She hears him, but gives no sign. And he, having watched her inscrutably for a while, withdraws in silence, glancing back disapprovingly from her to the open windows, through which clouds of mosquitoes and other insects are streaming continuously, attracted by the light inside.

Around the bare electric bulb, which the white saucer-shaped shade does not hide, they circle in ever-increasing density, almost obscuring its light. Their numbers make them unrecognizable in flight, as they are in death, and their scorched, charred, singed, or still spasmodically twitching bodies pile up on the tabletop and finally overflow on to the bare unpolished floorboards beneath. Here they are hidden by the table's circular shadow, though a few feebly and lopsidedly drag their maimed legs, fire-shriveled wings, and broken antennae some inches further, before they finally twist into lifeless shreds of detritus.

4

Waited upon by the disapproving servant, the husband is eating his dinner in the dining-room. The girl has stayed on the roof where it's cooler. It's not unusual these days for the meal to be served and eaten without her. Since the hot weather started she has no appetite. She has not been long in the country, and her constitution is not y

et adjusted to the torrid, unhealthy climate. Besides, the pair have nothing in common; although they have only been married a year, neither enjoys the company of the other.

The man has a curious inborn conviction of his own superiority which is quite unshakeable. All his life he has bullied and browbeaten those around him by his high-and-mightiness and his atrocious temper. As a boy he terrorized his entire family by his tantrums, when, if thwarted, he would throw himself on the floor and yell till he went blue in the face. It has been much the same ever since. Everyone's terrified of his rages. He has only to start grinding his teeth, and people fall flat before him.

His wife is the only one who doesn't seem to succumb, which of course annoys him. Besides, he has other things against her : such as her not being a social success, and her inability to run the house efficiently. Actually, she's as out of sympathy with domestic and social affairs as he is with intellectual pursuits, and scarcely attempts to control their numerous servants of different races. Some of these have been in the master's service before his marriage and resent her presence, putting the others against her and deliberately making her inefficiency more obvious.

The man in the dining-room is aware of all this, as he is of the significance of the fact that his dinner is being served, not by the butler who must have been forced to give up his place, but by his own personal boy. The severely ascetic grey-bearded Mohammedan has been with him ever since he first came out here as a junior. Of course his position now is much higher, but he has a perpetual grievance because it's not higher still, and considers that he's unfairly treated, passed over instead of promoted, unaware of the extent to which arrogance and bad temper prejudice his advancement.

His boy occupies a privileged place in the household, not only because he's been with him longer than anyone, but also because waiting upon his person implies a certain intimacy, as his presence now indicates. He knows all is not well between his master and the young wife, whose neglect of her domestic duties on which his comfort depends is typified by her leaving the windows open, so that the house is full of mosquitoes. It is to show his sympathy, and his wish to atone for her deficiencies, that he is in attendance so anyway he wants the other man to believe wearing his huge, heavy, elaborately wound turban, instead of taking his ease and enjoying the ministrations of his own properly subservient wife.

It is true that the master relies upon him, perhaps more than he knows. He would prefer to employ only Mohammedans, regarding them as more trustworthy than the local people, and only does not do so because government policy is against such discrimination. He dislikes the volatile inhabitants of the country, seeing them as irresponsible and amoral, their natural gaiety offensive to his puritanism. He is always at pains to be scrupulously fair in his dealings with them, but his attitude makes itself felt, and arouses hostility. However, as the natives are lighthearted and not much interested in the white people, their antagonism is expressed mainly in the form of mockery and they have named him Mr Dog Head — one doesn't at once see why.

Aggressive and overbearing physically as well as by nature, his arrogance makes him look taller than he really is, lean, muscular, tough and bony, with bright blue eyes that can flare up like rockets. The reddish tinge of his close-cut hair has been lightened by exposure to the tropical sun, and it clings to his skull like short fur. Without being exceptionally hairy, his arms share this close pelt, which appears to cover his whole body. Although he wears neither tie nor jacket, his shirt is immaculate, and he has changed for dinner into white trousers, instead of the shorts he wears during the day.

He eats fast, like someone who has to catch a train. Of course he conveys the food to his mouth silently and in the orthodox way; yet his jaws seem to close with a snap, he is already busily collecting the next mouthful with his knife and fork while still masticating the last. Nevertheless, it would be distinctly far-fetched to say there was any resemblance to a hungry dog in the eagerness with which he consumes whatever is on his plate, leaving it perfectly clean.

Mosquitoes are starting to penetrate into the room. It's impossible to keep them out as there are no doors, only wooden panels fixed to the door frame, so that air can circulate freely. Mohammed Dirwaza Khan has stationed a couple of boys outside with orders to hold up a net from wall to wall. But their arms are aching, they feel they've been most unfairly conscripted for this extra job, and they begin muttering rebelliously in voices that reach the diner's sharp ears.

He catches the eye of his servant, who is already moving to clout them into obedience, and just perceptibly shakes his head. He has finished. Pushing away his plate he stands up, ignoring the pink confection served for dessert as a traditional concession to the supposed sweet-tooth of his wife he never touches it. On the way out he smiles at the Mohammedan, briefly showing his teeth; large, white and strong, they suggest a wolf more than a dog.

Throughout the meal he's said not a word to the man. Since he still doesn't speak and only smiles at him in passing, it's hard to say why he now seems to show more than the normal goodwill towards him almost familiarity — or how his smile exceeds the permissible, or fails to comply with conventional standards of conduct, or appears indiscreet.

The recipient of the smile notes the slight excess if that's what it is - with gratification. It accentuates the

perfection of his behaviour in acknowledging it only by bowing his head, without overstepping formal correctness or discretion in the slightest degree. In fact, an on-looker would see no difference between this salutation and the bow he invariably makes when his master passes on his way out of a room.

All the same, he is satisfied that his leisure has not been sacrificed in vain. And in future he will be more of a tyrant to the rest of the staff, because of the strengthened solidarity he feels with the man who has just left him.

5

The upper floor of the house is divided into three : a middle room into which the stairs lead, and a bedroom on each side. The bedrooms too are without doors, each door frame provided with two wooden panels which spring back into place after being pushed apart, a foot or two of vacancy above and below.

The central porch with its flat roof is reached by long windows from the middle room, which contains some cheap cane furniture and a larger piece that seems to have overflowed from one of the bedrooms. This is a wardrobe, made in the local jail, out of some dark reddish wood which always feels slightly sticky to the touch. Bottles, glasses and siphon stand on a table. In the middle of the ceiling a big fan circulates sluggishly, stirring up the hot air.

The wire screens are now closed over the windows and seem to exclude any coolness there might be outside. Yet the girl sits as close as possible to one of the windows, straining her eyes to read by the inadequate light from a bulb dangling far above; she can't bear to switch on the table lamp, which gives out more heat than light.

Mr Dog Head, a rolled-up newspaper in one hand and a wire fly-swatter in the other, prowls round the walls, methodically exterminating mosquitoes. There are so many of them that their high whine is audible above the whirring of the fan and the sound of his movements.

He realizes that he'll never be able to kill them all and suddenly becomes exasperated, though not so much by the mosquitoes as by the girl's silence and immobility, and by the way she's taking no notice of him. It always irritates him to see her sitting about reading; that she should go on even when he's in the room seems a deliberate insult. His lordliness affronted by her lack of attention, he makes a wild swipe, simultaneously muttering something like, ‘It's really too much . . .’ which he alters to an accusing: ‘Is it too much to ask you to keep the screens shut ?’ gazing accusingly at her.

To his wife, there seems no point in answering. She feels that it's utterly futile to try to talk to him. She might as well talk to the wall, for all the possibility of communication between them. She keeps her eyes fixed on her book as though too absorbed in her reading to hear him.

Into her continued silence, he ejects:

‘Anopheles! How many times have I told you they're deadly to me ?’ Identifying a mosquito by its trick of standing on its head, legs crossed over its back, as it hovers with wings extended, he crushes it with the paper, adding one more to the innumerable brownish blood smears on the wall.

‘That devil's had somebody's blood already!’ He again looks at her accusingly, as if she were to blame. As she's still silent, apparently absorbed in the book, he becomes determined to make her attend to him, demanding indignantly: ‘Do you want me to go down with malaria?’

‘No, of course not.’ She sees that she can't put off talking to him any longer, and reluctantly raises her head, confronting his angry face; it looks to her hard, blank and impenetrable as a wall, with two blue glass circles for eyes above the hard, almost brutal mouth.

What possible contact can she have with the owner of such a face ? It half frightens her. (After all, she's only just eighteen, and he's double her age.) Feeling bewildered and helpless, she wonders why she's been pushed into marrying him.

'Have you taken your quinine ?' is all she can find to say. She deliberately makes her face blank to hide her apprehension, with the result that she looks almost childish, her badly-cut hair hanging down by her cheeks. Her eyes are slightly inflamed by the glaring sun, and from trying to read in a bad light, and she keeps rubbing them like a little girl who's been crying.

Her words irritate him almost as much as her pale face, with its faintly bloodshot eyes, the vague, blank expression of which makes him angry because it seems so insulting, as though she were miles away. He too wonders why they are married; why did he ever allow her mother to persuade him into it ? He feels he's been tricked which isn't far from the truth. But none of this is clear in his head; he is only aware of the inflaming of his permanent grievance against life in general, and her in particular. He blames her for everything. She gets on his nerves so much that he moves his hand as if he meant to hit her, deflecting his aim at the last moment and squashing another mosquito instead.