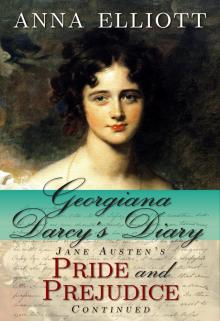

Georgiana Darcy's Diary: Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice continued

Anna Elliott

Georgiana Darcy’s Diary

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice Continued

Anna Elliott

with illustrations by Laura Masselos

a WILTON PRESS book

Text copyright © 2011 Anna Elliott

Illustrations copyright © 2011-2012 Laura Masselos

All rights reserved

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s (or Jane Austen’s) imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

For more information, please visit www.AnnaElliottBooks.com. (Or visit Anna’s catalog for small-screen devices at m.AnnaElliottBooks.com.)

Anna Elliott can be contacted at [email protected].

Table of Contents

Title and Copyright

Table of Contents

About

Author’s Note

Thursday 21 April 1814

Friday 22 April 1814

Saturday 23 April 1814

Sunday 24 April 1814

Pemberley Ladies (illustration)

Monday 25 April 1814

Tuesday 26 April 1814

Wednesday 27 April 1814

Thursday 28 April 1814

Friday 29 April 1814

Saturday 30 April 1814

Sunday 1 May 1814

Monday 2 May 1814

Tuesday 3 May 1814

Wednesday 4 May 1814

Mr. Folliet (illustration)

Thursday 5 May 1814

Friday 6 May 1814

Saturday 7 May 1814

Sunday 8 May 1814

Monday 9 May 1814

Tuesday 10 May 1814

Wednesday 11 May 1814

Thursday 12 May 1814

Friday 13 May 1814

Saturday 14 May 1814

Monday 16 May 1814

Tuesday 17 May 1814

Wednesday 18 May 1814

Thursday 19 May 1814

Quadrille Practice (illustration)

Friday 20 May 1814

Saturday 21 May 1814

Monday 23 May 1814

Tuesday 24 May 1814

Thursday 26 May 1814

Bridge at Pemberley (illustration)

Friday 27 May 1814

Saturday 28 May 1814

Monday 30 May 1814

Tuesday 31 May 1814

Wednesday 1 June 1814

Dear Reader

Pemberley to Waterloo

About the Author

Credits

About

Mr. Darcy’s younger sister searches for her own happily-ever-after…

The year is 1814, and it’s springtime at Pemberley. Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy have married. But now a new romance is in the air, along with high fashion, elegant manners, scandal, deception, and the wonderful hope of a true and lasting love.

Shy Georgiana Darcy has been content to remain unmarried, living with her brother and his new bride. But Elizabeth and Darcy’s fairy-tale love reminds Georgiana daily that she has found no true love of her own. And perhaps never will, for she is convinced the one man she secretly cares for will never love her in return. Georgiana’s domineering aunt, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, has determined that Georgiana shall marry, and has a list of eligible bachelors in mind. But which of the suitors are sincere, and which are merely interested in Georgiana’s fortune? Georgiana must learn to trust her heart—and rely on her courage, for she also faces the return of the man who could ruin her reputation and spoil a happy ending, just when it finally lies within her grasp.

Georgiana Darcy’s Diary is Book 1 of the Pride and Prejudice Chronicles and is approximately 67,000 words in length.

Author’s Note

Of all the wonderful secondary characters in Pride and Prejudice, Georgiana Darcy has always been my favorite. In Jane Austen’s original text, we never actually hear her speak a single direct word; any dialogue she has is merely summarized by the narrator. But to me, that only made her more intriguing. Just who was she, this painfully shy younger sister of the famous Mr. Darcy—a girl with a large fortune of her own, who at the age of fifteen was so very nearly seduced by the wicked Mr. Wickham?

Jane Austen herself gave her own family a few tidbits about what happened to her characters after the close of Pride and Prejudice. Kitty Bennet married a clergyman near Pemberley, while Mary married one of her uncle’s clerks. But so far as is known, she never hinted at what happened to Georgiana Darcy after her brother married Elizabeth. For myself, I always felt that Georgiana Darcy ought to marry Colonel Fitzwilliam.

The modern reader may object that the two of them are cousins. But in Jane Austen’s world, marriage between cousins wasn’t considered at all improper—it was often absolutely encouraged. Queen Victoria married her first cousin Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and theirs was one of the happiest love stories and most famously successful marriages of the age. In fact, Jane Austen herself wrote about such romance in Mansfield Park: Fanny Price and Edmund Bertram are first cousins.

Of course, you’ll have to keep reading to see whether, once I started writing their story, Georgiana and Colonel Fitzwilliam agreed with me that they were meant to be together!

One further note: I can’t begin to match Jane Austen’s immortal writing style, and wouldn’t even pretend to try. That’s one reason I chose a diary format for this story. I would never aspire to imitate Jane Austen or compare my work to hers. Georgiana Darcy’s Diary is meant to be an entertainment, written for those readers who, like me, simply can’t get enough of Jane Austen and her world.

Thursday 21 April 1814

At least I was not in love with Mr. Edgeware.

That sounds as though I am trying to salvage my pride, but I am truly not. I hate lying—especially to myself. And there is small point in keeping a private journal if I am only going to fill it with lies.

So, I was flattered by Mr. Edgeware’s attentions. I liked him—or at least, I thought I did. But love? No.

Though I am sure my Aunt de Bourgh would say that is neither here nor there in considering whether Mr. Frank Edgeware and I should marry.

I don’t seem to have begun this story at all properly. I have been keeping a diary on and off since I was ten, but I have not written an entry in a year or more. Maybe I am out of practice with setting down the events of the day. I am not even entirely sure what made me pick up this notebook—a red leather-bound book of blank pages that Elizabeth gave me for Christmas. Except that the memory of what happened today feels like a festering sore inside me—and maybe writing it all down here will let the poison out.

To explain more clearly, then, Mr. Frank Edgeware is the youngest son of Sir John Edgeware of Gossington Park. Mr. Frank has been staying here at Pemberley for the last three weeks, one of the house party my aunt has imposed upon us all. He is a handsome man—really, a very handsome man, with dark hair and melting brown eyes and a sallow, lean kind of good looks.

Aunt de Bourgh—small surprise—has thrown us together a good deal, and he has been my partner at whist, has accompanied me for walks and rides about the grounds. We seemed to have so much in common, he and I. He would ask which poets I liked best, and when I mentioned Mr. Cowper, he would wholeheartedly agree that Mr. Cowper’s poems were masterpieces of language and feeling. The same with music. I spoke of Mr. Thomas Arne’s operas, he professed himself a great lover of Artaxerxes, as well.

I can see now, of course, that I was an idiot t

o be so taken in. Anyone would think that after George Wickham’s courtship, I would have learned to spot a fortune hunter. But at the time I had not a single suspicion that Frank Edgeware was anything but sincere.

Until this morning, when I chanced to be walking in the rose garden. I was on a path screened by a thick row of bushes and overheard Mr. Edgeware speaking to Sir John Huntington on the other side of the shrubs. They could not see me, of course, but I heard every word.

Sir John—he being another member of the house party, a goggle-eyed man with plump hands and greasy hair—asked Mr. Edgeware how he was progressing with Miss Georgiana Darcy.

And Mr. Edgeware laughed and replied that he fancied he would succeed in winning my hand in marriage, all right, and confidently expected to be wedded to me by the end of three months’ time.

“And thank God that when we’re wedded,” he said, “I won’t have to listen and pretend to agree while she maunders on about poets and musicians.” He laughed again. “It’s a good thing she has a fortune of thirty thousand pounds. She’s a nice enough little thing, but ditchwater dull.”

My whole body flashed hot and cold, and just for a second I wanted to smash my way through the bushes and confront the pair of them. But I did not. If I have not yet learned to judge men’s characters, I at least know my own well enough. And I knew I would never in three hundred years work up the nerve for a dramatic confrontation of that kind. Or if I did, I would stand there, red-faced and stammering trying to to think of the perfect retort. Which would probably come to me at three o’clock the following morning, but not before.

Sometimes I hate being shy.

So I simply turned and walked—very quietly—away, before the men could guess they had been overheard.

Mr. Edgeware came to sit with me on the settee after dinner this evening, just as usual, and smiled into my eyes.

I wonder, now, that I never noticed how calculated his smile is. I can just imagine him practising it every morning in front of the mirror.

At any rate, he asked me whether I would consent to play for the party this evening. He had been dreaming all day, he said, of hearing me play again on the pianoforte.

So I said that I had been practising a waltz by Mozart, and when he replied that he was absolutely enchanted with Mozart’s waltzes, I smiled at him very sweetly. “Are you really?” I said. “They are nice enough, I suppose, but ditchwater dull.”

It was some consolation, at least, to see the smile slide off his handsome face and the way he went red right to the tips of his ears. For once he had absolutely nothing to say; he just sat there, opening and closing his mouth like a fish out of water.

My affections truly were not engaged. It is only my pride that is hurt, not my heart. And really, Mr. Edgeware’s deceit of me is incredibly petty when weighed against the other news of the day, which is that victory has been won over France at last.

Come to think of it, I really should have made that the opening of this journal entry, not the tag end; it’s far more important than my own concerns. But—peace. It is such momentous news that I think everyone can scarcely take it in. Britain has been at war with France since before I was born—all eighteen years of my life—and I’d come almost to take it for granted. I think many people would say the same. But it’s true—the latest word is that the Emperor Napoleon has been forced from his throne and is to be exiled. Our troops will be returning home.

I got all this from the newspapers, not from any note or letter of Edward’s. I’ve not heard a single word from Edward since his regiment was called to foreign duty more than a year ago. Not since the last night I saw him, at the Pemberley Christmas ball.

But he can’t have been killed—he can’t. I’ve read the casualty lists in the papers every day, and his name has never appeared.

Still, I wish—

But I cannot write any more. It is very late. I am writing perched on the cushioned window seat, watching the moonlight glimmer on the lake in front of the house. My fingers are cramped with writing, and my ink is growing thin from being watered so often.

Friday 22 April 1814

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a young lady of rank and property will have packs of money- or land-hungry suitors yapping around her heels like hounds after a fox.

I said as much to Elizabeth this morning, when we were looking over my new gown for the ball next month, which had just arrived by special delivery from London.

Elizabeth laughed and said she quite liked that comparison, because she could imagine my aunt, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, as a huntswoman, cheering on the packs of suitors with cries of Yoiks! and Tally-ho!

But then she stopped laughing and said, looking at me, her gaze serious for once, “There’s no one among the young men staying here you like, Georgiana? Truly? Mr. Folliet? Or Mr. Carter, even?”

I hung up the gown we had been examining in the wardrobe. It is very pretty: pale peach silk with an overdress of cream-coloured gauze, all embroidered with tiny rosebuds. And I am sure I would like it even more were it not further evidence that my aunt has determined to see me married within the year, it being a scandal that any niece of hers should have reached the age of eighteen—and had two Seasons in London—without being at the very least engaged.

“None,” I said. “Or rather, I like some of them. But not that way. I don’t wish to marry any of them. Unless—” I stopped as a thought struck me coldly. “Does my brother … does he wish that I should?”

“Of course not! Not unless you want to, that is.” Elizabeth tilted her head to look at me from where she was perched on the edge of my bed. “Georgiana, you cannot truly think he would allow you to be pushed into a marriage just to please your aunt?”

“Yes—I mean, no, I do not think that.”

Elizabeth said, “Listen to me. Darcy agreed to this house party scheme of Lady Catherine’s because he worries—as I do!—that you go out too little into society. That you have small chance of meeting any nice, agreeable young men. But that is all.” She watched me for a moment, her dark eyes thoughtful. Then she said, “You could speak to him, though, if you truly hate all this so much.” She smiled. “He doesn’t bite, I promise you. He wouldn’t even be angry.”

“I know.” I do know. I think. It is just that my brother Fitzwilliam is eleven years older than I am. And he has been my guardian since I was ten years old.

He has been such a good brother to me. But I think I am a little in awe of him, still.

More than a little.

And I know I have already given him far more worry than he deserves.

“But it’s all right,” I told Elizabeth. “It’s just … that I’m happy here. I love it here at Pemberley with you. Unless—” My whole body flashed hot and cold all over again. “Unless you feel I’m in the way? If you’d prefer to have the place to yourselves, without your husband’s unmarried sister—”

“Of course not!” Elizabeth said. “Of course I don’t feel that.”

It seems strange, now, to think that I almost dreaded my brother’s marrying Elizabeth. Not that I did not like her—because I did like her very much, right from the first time I was introduced to her. It was just that she was a stranger, moving into our family and our home. At least, that was how it felt to me at the time.

I have always hated change. I think maybe it started when my mother died—but now and for as long as I can remember, I have felt a sick, hollow feeling every time a round of changes comes. When I was first sent away to school—and then again when I had to leave. Even last year, when a storm blew down the oldest and tallest of the Spanish oaks on Pemberley’s lawn, I felt so grieved, silly as I knew it was.

But Elizabeth is not at all a stranger anymore—she feels almost like the sister I used to wish for when I was small. And—though it seems disloyal to say it—I can speak to her much more easily than I can to my brother.

“I was just saying to Darcy,” Elizabeth went on, “that it’s his responsibility to ve

t your potential suitors for me—no men allowed who live at more than a day’s travel from here, because if you married and went too far away, I’d break my heart missing you. I’d be perfectly happy to keep you here with us always. But—”

Elizabeth broke off. “Oh, well—haven’t you ever noticed the abominable habit newly married people have of wishing to see all their friends married, as well?” She spoke lightly. But all the same there was a look on her face that made me feel suddenly lonely. The way I feel sometimes when I see her and Fitzwilliam catch each other’s eyes and smile at each other.

They have been married for just over a year, now, and they’re so happy together it fairly hovers like a sunburst all around them; you can’t be in the same room with them and not realise how deeply and sincerely attached to each other they are.

Even my Aunt de Bourgh has stopped resenting my brother’s marrying Elizabeth quite so much. Though of course for my aunt, that means merely that she waits until Elizabeth is out of the room to speak of ‘my nephew’s unfortunate marriage’ in the same tones you might hear at a funeral.

Elizabeth only laughs, though, and says she’s glad, for it gives her the upper hand and makes Fitzwilliam feel he is lucky she consented to marry him, despite his horrible relations.

“Mr. Edgeware looked quite bereft last night,” Elizabeth went on. “When you asked me to turn music pages for you at the pianoforte instead of him.”

“I imagine he did.” And then I told Elizabeth what had happened, everything of what I had overheard Frank saying in the garden to Sir John.

Elizabeth has been looking a little pale and tired, lately. Or tired for her. But her cheeks flushed bright scarlet at that, and she looked furious. She laughed, though, when I told her of my revenge, and she said, “Oh, well done! Exactly what he deserved.” Which—almost—took the sting away from the memory.

Then she hugged me again and said, “You’re not dull—and anyone who thinks you are is a blind fool and doesn’t deserve you. But Georgiana”—she looked at me—“never mind your aunt’s contenders, are there no other young men you might like? You’re not”—all of a sudden her eyes went wide and alarmed—“you’re not still in love with Mr. Wickham, are you?”

I smiled at that. Even if the smile tasted bitter on my lips. “Good heavens, no. I promise you, whatever else I am, I’m not in love with Mr. George Wickham.”

Elizabeth let out her breath. “Well, thank goodness for that, at least. But … but there’s no one else? Truly?”

I swallowed. And then I shook my head. Perhaps if I had grown up with four sisters as Elizabeth had I might find confidences easier.

But as it was, my throat closed up and my palms went clammy at even the thought of telling Elizabeth that there was someone else. I have never spoken of it to anyone, not ever. But there is Colonel Edward Fitzwilliam, the man I have been in love with since I was six years old.

Saturday 23 April 1814

I’m sitting-up in bed with the candle on my night table lighted and flickering beside me. It has stopped raining at long last, but I can hear the wind outside howling in the chimneys.

All the rest of the house is asleep, even my Aunt de Bourgh. She sleeps poorly and is often wakeful until past midnight. But I have just heard her long-suffering maid Dawson go past my door on her way to the servants’ wing and her own bed, so my aunt must be truly settled now. My aunt keeps Dawson until late most nights, making her read from a book of sermons and rub her back until she can drop off.

Two things happened today.

The first was a letter from Edward. Though it was sent to my brother, not to me.

Fitzwilliam had been up and riding out early to consult with his farm bailiff about the spring planting. But he came in for breakfast and opened the letters piled beside his place at the table. When he got to Edward’s, I felt my heart jump, because of course I recognised the handwriting on the envelope.

It seemed an eternity before he looked up at Elizabeth and said, “It’s from Edward. He says he has been wounded and granted a leave of absence, and would like to spend it here.”

I gasped despite myself and Elizabeth gave a little cry of distress and said, “Wounded? Oh, no, poor Edward, is he seriously hurt?”

My brother glanced through the letter again and said, “He says it’s nothing much, just a musket ball in his shoulder. He took it at Toulouse, he says—just before it was announced that Napoleon had surrendered.”

And Elizabeth said, “That does not signify. Men always lie about how badly they’re hurt, and soldiers are worst of all. But if he is well enough to write and to travel, he can’t be too badly injured.”

I did not say anything. My heart was beating too quickly and too hard.

I read of the battle for Toulouse in the newspaper reports. Nearly five thousand British and allied soldiers were killed. And the French lost three thousand of their own.

And all for nothing, too—because Napoleon had abdicated four days before the battle occurred. If only word had reached Toulouse in the South, all those lives might have been spared.

Still, as Fitzwilliam spoke, I drew what felt like my first breath in all the time Edward has been gone. He may have been wounded. But his letter shows that he survived the fighting, and now he’s coming home.

The second event—

I suppose today’s second occurrence is what is keeping me awake tonight. Even more than Edward’s letter.

A travelling band of gypsies came to the house and offered to entertain us and tell fortunes after supper.

My aunt looked as horrified as though she had uncovered a dish at dinner and found a plate of wriggling worms instead of pork cutlets. But Elizabeth had already gone to the window and looked out and seen them grouped around the front door. They looked poor and wet and miserable and there were several little children without any shoes, their feet almost blue with the cold.

Elizabeth turned to my brother and said, “Please, Darcy.” And my brother nodded and said, “Very well, let them come.”

I truly did wish, then, that I was more like Elizabeth. I had thought of slipping up to my room when no one was watching and finding some money to give to them. But I should never have been bold enough to speak up in front of everyone as she did.

The music was beautiful in a wild, lilting way. One of the men played a fiddle and some of the women played tambourines and danced. And then one of the oldest, a little, wizened old woman with a dirty red scarf wrapped around her head and with her body swathed in so many shawls one could scarcely see her shape, offered to tell fortunes.

She turned to my cousin Anne first and asked if she would like her fortune told, and Anne sat up and looked quite bright and interested. But then, of course, she looked at her mother. My aunt could not quite bring herself to look at the old gypsy woman directly, but she sniffed through her nose and said, “Anne, you are going to have a headache. You must go up to your room at once and go to bed. I will send Dawson to you with some barley water for you to drink.”

If I am honest—which I suppose I have, after all, resolved to be—I will say that I have never managed to like my cousin Anne very much. No one could really like my cousin Anne. My aunt decided when she was a child that Anne was of a sickly disposition. Whether it is true or not, I do not know. I have never known Anne to be really ill—not with any identifiable malady, at least, nor even a serious one.

But Aunt de Bourgh has convinced Anne herself of her poor health so completely that Anne does nothing but sit in the warmest place in a room, smothered in lap rugs. She scarcely ever speaks, save to talk in a dull, colourless voice of the pains in her head or her eyes or her lungs—or whatever other part of her Aunt de Bourgh has decreed is feeling poorly that day.

Tonight, I stood up and said, “Anne, we could go and have our fortunes told together, if you’d like. You needn’t go alone.”

But all the life and colour had already gone out of Anne’s face as my aunt looked at her, and she only muttered so

mething indistinguishable and drooped upstairs to bed.

So I went over on my own to the small table where the old gypsy woman had set herself up in a corner of the room.

Seen up close, the old woman’s face was wrinkled and leathery as a dried apple, and her eyes were rheumy. Her hands were big, though—gnarled with age, but almost as strong-looking as a man’s. And she took my hand in one of hers and looked into my palm.

“Ah.” She drew in her breath and looked up into my face, nodding and bobbing her head. She had a cracked voice and spoke almost in a sing-song manner. “A happy future here, no question of that. I see a man coming into your life, my dear. He will be handsome and brave and strong and kind and wealthy, very wealthy, and—”

I suppose I was still feeling angry with my aunt, and impatient with Anne for never standing up to her, because I interrupted the old woman before she could say any more. “Hadn’t you better stop while you’re ahead?” I asked. “There aren’t all that many more nice, promising-sounding adjectives you can use to describe this mysterious gentleman.”

The old gypsy blinked at me for a second. And then she threw back her head and laughed. Her speaking voice might be cracked, but she had a nice laugh, throaty and full.

“Ah,” she said again. And then she peered more closely into my face. “Most girls I give fortunes to—” She hawked and spat right onto the carpet, which I am sure gave my aunt fits if she was watching. “Empty-headed little dolls. They want to hear nothing but that they will meet a man. A handsome man, very rich.” She closed one eye in a wink. “Usually pay extra if I tell them they’ll be married within the year.”

I laughed at that. I found myself liking the old woman despite myself.

“But you—very well, you I will give a real fortune.” She took my hand again and looked into my palm, her whole face twisted this time into a fierce scowl of concentration. “You are strong. Stronger than you think, and with more courage than you believe yourself to have.” Her voice was no longer sing-song, but somehow it still sent a trickle of cold down my spine. “I see a change ahead for you. A change in your life, in yourself.” She closed her eyes in another wink. “I will not argue if you pay me extra, you understand. But this I would tell you in any case. You do not trust or love lightly—you do not believe you can trust your own heart or your own eyes to tell you true.” She folded my fingers over my palm and squeezed my hand, her rheumy eyes still on my face. “But I think you may trust your heart from now on, for this I will say: I see love. I see an old love returning to you, and very soon.”

Sunday 24 April 1814

It has occurred to me that perhaps I should have begun this journal by introducing the members of our house party properly and one at a time. Of course, no one reads this diary but me—but one never knows. Maybe some members of a future generation will come across it one day in a musty old trunk and waste countless hours trying to puzzle out who everyone is. So for the sake of my imaginary great-grandchildren—or maybe great-nieces and -nephews—I will set full descriptions of each guest at Pemberley down here and now.

Besides, it is raining again, so that we are trapped in the house for the morning. I am longing to practice the pianoforte—but not with such an audience about. I am always too nervous of making mistakes to concentrate on the music when there are too many people listening to me play.

And more importantly, the instant I stop writing, my Aunt de Bourgh will begin her inevitable scolding because I only played last night and didn’t join the others in dancing. Elizabeth said she was feeling a bit tired and not up to dancing, so she sat beside me and turned the pages. I hope she’s not unwell. She looks a little pale again today, and when I sat next to her at breakfast, I noticed she took only some dry toast and ate scarcely a mouthful of that.

At any rate, the house party: Firstly, there are my brother, Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy, and his wife, Elizabeth. Though perhaps they don’t count, because they live at Pemberley year-round. Still, I said I would describe everyone, and they make for an easy place to begin.

My brother is eleven years older than I am, which makes him nine-and-twenty this year. He is tall, with dark hair and dark eyes. He is very handsome—if I can say that about my own brother.

I remember when I was small, he seemed so very grown-up to me. He had already left the schoolroom before I even entered it, and by the time I was four, he was already off at school and only came home on holidays. I used to love those times. He would always bring a present for me—a doll or a hair ribbon or sugared lemons—when he came home. And I remember when I was very little—two or three, maybe—and visitors would come to call, he would always carry me around on his shoulder, because I was too shy to speak to anyone.

But of course there was too great a difference in our ages for us to be close confidants.

Our mother died when I was six. And then when I was ten, our father died, as well. Fitzwilliam was left to become my guardian—and to run the estate at Pemberley. The park and the timber and all two hundred tenant farms.

He felt the responsibility very keenly, I know. He had always been sober and serious, and after that he grew even more so.

He did make sure I was happy at school—and he always came home with me to Pemberley or to the London house when there was a school holiday. But I did not wish to worry him with my concerns, so I cannot say I ever spoke to him very much of how I felt.

And now—now he is still a truly good brother. And since he and Elizabeth have been wedded, he smiles and laughs far more than he used to. But I still … I don’t know. Perhaps he still thinks of me a little as the ten-year-old girl that suddenly became his responsibility to be almost a father for.

And I know that with him, I still feel at least in small part like a child in the schoolroom, looking up at the grown-up’s world. Even if I am now eighteen.

Elizabeth is my brother’s wife. Though of course I said that already, didn’t I?

She was Elizabeth Bennet before she married him, of Longbourn in Hertfordshire. Elizabeth has dark hair and creamy pale skin. She has lovely dark eyes, though she is not a great beauty—at least to anyone who first meets her. But somehow the moment she smiles and starts speaking, she is beautiful. She can light up a room just by coming into it and charm anyone from the boy who cleans the knives and boots all the way up to an elderly duke.

I would not trade places—I suppose we none of us really want to be anyone but ourselves. But if I am being truthful, I do sometimes wish I could be more like her. Light and bright and sparkling and never seeming to worry over knowing the right thing to say or what other people will think of her.

I think Edward—Colonel Fitzwilliam—was a little in love with her before she married my brother. But of course, Edward is the younger son of an earl, which means he’s expected to marry both position and fortune. Though I asked Elizabeth about him once—it was last year when we were afraid he might be sent off to fight in the Americas—and she said that she liked Edward very much, but that if he had been really in love with her, her lack of fortune would have mattered as little to him as it did to my brother.

But I am wandering off the subject.

Caroline Bingley, the sister of my brother’s friend Charles, is staying with us for a while, since Charles’ wife—Elizabeth’s sister—Jane is confined with the birth of their first child.

Caroline dresses in bright colours and heavy, stiff brocades, and is handsome in a tall, imposing way, with dark-blonde hair and blue eyes, like a picture of a Viking maiden I once saw in a book. She and I are friends, of a sort.

Which means that before my brother married Elizabeth, Caroline hoped desperately to marry him herself. And she tried her hardest to ingratiate herself with me as a way of growing closer to him.

That sounds as though I resent her for it—and maybe I did at the time.

Caroline is the kind of girl I am always a little afraid of—or at least intimidated by. She has a strong voice and very decided opinions, and a very sharp tong

ue when she is speaking of anyone she dislikes—of which there are many.

I used to hate it when she would gush praises over my sketch work and my pianoforte playing, because I knew perfectly well that she would have never said two words to me if I had not been Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy’s younger sister. And I never knew what to say in return to her compliments, because I would keep imagining the things she probably said about me behind my back.

My thanks always sounded so chilly and stilted in comparison to her (albeit insincere) words that I would feel suddenly conscious and more intimidated by Caroline than ever—and that would make me sound less friendly even than before.

Now, though—now Caroline seems to me a little like a child’s balloon toy that’s been pricked and had the air let out of it. That my brother could truly have fallen in love with Elizabeth instead of with her has left her shaken, I think, as though the ground under her feet has shifted and tipped and she is not quite sure now where she stands.

I found her just the other day standing in the morning room and looking up at herself in the mirror over the mantle with her hands clenched and her eyes filled with tears. And when she heard me behind her she whirled round and clutched my hand and said, “I’m handsome, Georgiana, aren’t I?”

I was startled—for I had never seen Caroline cry before. But I said, “Of course you are, Caroline. But you scarcely need me to tell you that, do you? Not when you have both mirrors and men.”

Caroline scrubbed at her eyes and said, “I mustn’t cry. It makes me look a fright. It’s only … I’ll be four-and-twenty on my next birthday, and I always thought I’d be married by now. Married and with a home and children of my own, just like my brother and Jane are going to have.”

Since then, she has seemed a little more in control. But still, I’m sure she wishes the men of the party were taking more of an interest in her.

And speaking of the men, there are four gentlemen staying here at Pemberley.

Or rather, we had four until yesterday, when Mr. Edgeware abruptly remembered a previous engagement elsewhere. I have no more faith in his engagement than in his professed admiration of Mozart. But I am relieved that I need not meet with him again.

So now there are only three men here, besides my brother.

Sir John Huntington I suppose I have already described, but for the sake of completeness I’ll put him down again here. He is of course well born, or my aunt would not have considered him a contender for my hand. He has prominent gooseberry-green eyes and small, plump hands and greasy reddish brown hair and so far I have heard him speak of nothing but playing cards and horses. But I suppose to be fair I should not hold that against him, he may be very nice.

Except that he laughed at what Mr. Edgeware said about me. Which means that if he has a nice disposition under all the greasy hair and talk of horses, he will be a hundred years old before I ever find it out because I would rather chew on rusty nails than ever speak to him again.

The other two gentlemen I’ve spoken to scarcely at all, since they only arrived here at Pemberley four days ago. One is the Honourable Mr. Hugh Folliet, who is the grandson of the Earl of Cantrell. The old earl’s daughter, Mr. Folliet’s mother, and Aunt de Bourgh were at school together years ago, which is how Mr. Folliet comes to be staying here.

He looks to be about twenty-five, or a few years more. He has dark hair and dark eyes and he’s very handsome—really, one of the most handsome men I’ve ever seen, like a knight in an old romance. Sir Lancelot, maybe, if Lancelot wore buckskin breeches and stiff white cravats.

The other gentleman is Mr. Carter, a friend of my brother’s from his school days. And he, at least, is certainly not one of my aunt’s candidates, because he is a clergyman, and quite poor to judge by the threadbare collar of his coat and the cracked soles of his boots. But I like him—or at least I like what I’ve seen of him. He has sandy fair hair that is forever flopping down over his forehead into his eyes and he speaks with a slight stammer. But he looks thoughtful and intelligent, and I think he must be kind, as well. The other night my cousin Anne was sitting huddled by the fire as usual, and he sat down next to her and stayed there speaking with her for quite some time. Her usually sallow cheeks flushed with the heat of the fire and she smiled very often at whatever he said and really looked quite pretty.

I suppose that actually I have given a fairly complete sketch of my cousin Anne already, without entirely meaning to. But for the sake of completeness, I will put her down again here. She is my brother’s age, or nearly so—she will turn twenty-nine in July. But she looks far younger because she is so very thin and small. Her hair is fair, straight and baby-fine, and she has a small, pale face that might be pretty if she did not always look so querulous and cross.

She must be horribly bored, though, so I can’t really blame her for being petulant at times. My aunt never allows her to read, for fear of straining her eyes, never allows her to ride or go out for a walk for fear of taking a chill. She’s not even allowed to embroider or paint or play the pianoforte for fear the effort will over-tire her.

I think I have mentioned it before, but my aunt is Lady Catherine de Bourgh. She is the daughter of my grandfather the earl, and the widow of Sir Lewis de Bourgh. She is—

How strange, I have known her all my life, but I have never thought about how to describe her before.

Aunt de Bourgh is a tall woman with a square-built, broad-shouldered frame. She never speaks of her age, but I should think she must be fifty, or perhaps a year or two more. She has bold, strongly marked features and dark hair threaded with grey that she wears piled atop her head, and she speaks with a deep voice, very loud and very firm.

I don’t suppose anyone could have read the past few entries in this diary without realising that my aunt is exceedingly proud and likes to order other people’s lives for them. And she likes to have things her own way. I was terrified of her when I was a child—I can just remember hiding behind my mother’s skirts one of the first times I was taken to visit her at Rosings Park, her estate. I can still see my aunt peering down her nose at me and booming out, “Upon my word, you seem to have entirely neglected to teach the child proper manners.”

I suppose I must still be frightened of her—otherwise I would simply have told her straight out that I do not wish to marry any of her parade of suitors.

And yet … I don’t quite know what it is I want to say. Save that it sometimes seems to me that anyone who makes other people as miserable as she does cannot be very happy herself.

And that makes up the whole of our house party here at Pemberley. I wonder if any of my subjects would recognise themselves if they read these descriptions without the names attached. I’ve never taken anyone’s likeness in just words before. It is more difficult than I thought.

I think I’ll try it with a picture, next. Here are all of the ladies in the morning room this morning, whiling away the hours and hoping the rain won’t last all day.