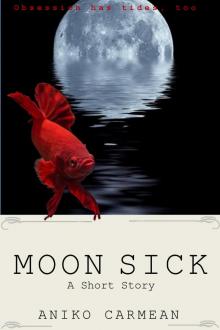

Moon Sick

Aniko Carmean

MOON SICK

Published by Odd Sky Books

First Edition: November 2014

Copyright © 2014 Erzsebet Aniko Carmean

Cover Art by Aniko Carmean, using DIY Book Covers

Editing by Jacinda Little

License

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/.

Disclaimer

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

MOON SICK

A Surreal Short Story

Aniko Carmean

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Moon Sick

Want More Surreal Fiction?

Get a Free Tarot Reading

About Aniko

Moon Sick

It’s Sunday, and I’m a few cars behind Charlotte and Lawton. We’re going to the Asian Grocery in Aqueduct, the part of town women shouldn’t visit after dark. I never liked the place, not even before the moon started falling and the whole world went to shit, but Charlotte thinks the Asian Grocery is an attainable adventure because she can speak Japanese and say hello in Korean.

Charlotte pulls into the lot for the strip mall, dodging potholes that are the first scourge of the moon’s descent. I go the opposite way and back into a space. My rear tire hits one of the larger holes, and I hope it isn’t damaged because I’ve already replaced three flats this month. While I wait for Charlotte and Lawton to go inside the store, I scroll through the pictures on my phone. Most of them were taken when the reports of the moon falling were relegated to those crackpot conspiracy shows on the AM radio. In my favorite photo, Charlotte sits with me in the writing workshop where the three of us met. She read my work and found symbolism. That was a shock. I didn’t write it on purpose. As for Charlotte’s stories, I could never see anything but her in them. We analyzed The Soft Moon by Calvino, joking about how “topical” it was (how little we knew!). Charlotte identified with the character who was looking through a telescope with awe at the magnificent approach of the moon, but Lawton shared the narrator’s disgust. I just felt excited. I still do. Yes, the moon is a ghastly colossus, a pocked and looming mass, but her crude, elemental pull is unadulterated arousal. The Lunatic Cult prays for the moon to fuse herself to the Earth in cosmic coitus. I just want Charlotte.

The automatic timer still hasn’t shut off the headlights on Charlotte’s car. I keep waiting.

Half a year ago, and much to the embarrassment of physics, eons of the moon’s infinitesimal and steady movement away from Earth suddenly reversed. The scientists still use their equations to explain that it will take another miracle to increase the moon’s orbital speed and prevent a collision, but equations are no better than bibliomancy or reading tea leaves. The moon will put herself in a new equilibrium, or she won’t. Only she knows for sure if she’s planning a crash-bam extinction event.

Charlotte’s headlights finally die.

I double-check that my doors are locked before I cross the lot. Looting is more common now, even when it’s not full moon. The Vietnamese Pho restaurant is out of business, and the place that cashes checks has ply board covering windows broken by high-tide quakes. Though it is January, a string of Christmas lights hangs above the doors of the Asian Grocery. “Fish – Almost Gone, Hurry,” is hand-printed on fluorescent yellow poster board.

Inside, I dodge behind a stack of empty crates, adjusting to air that is filthy with the scent of rot. Lawton and Charlotte peruse the meagre selection of battered vegetables. The transportation of goods is unreliable, and winter brought the first food riots to the bigger cities, where there was more competition for increasingly scarce commodities. It is nothing like last summer, when Charlotte convinced me to do my grocery shopping here by promising she’d go to dinner with me. The produce section was brimming with stacked stripes of multi-colored vegetables, many I didn’t even recognize. I got a bunch of grapes in a bag that was stapled shut. As I ate them the next day, I found one had been bitten. I imagined lips other than mine on the fruit, a strange tongue and fingers on what was supposed to be mine. I haven’t eaten a grape since then – and wouldn’t even if they were available.

Charlotte and Lawton leave the produce section with one destitute looking leafy green riding lonely in their cart. To keep out of sight, I go through the nearly empty freezer section and stand behind stacked bags of dried peppers. Diagonally across from me, Charlotte leans over a plastic container of homemade tofu. Sandy hair frames her ocean-lit eyes like a cove surrounding a bay. Lawton puts his arm around her waist like a man drowning, and memory slams me. Once, during the time when every weekend had the feel of a seaside vacation, we decided to play Twister. Lawton and Charlotte went the first round. Then I played the winner, Charlotte. We started at opposite ends of the colored mat, facing each other with our legs spread. Lawton spun the pointer, and began calling body parts and color pairs. With each spin, Charlotte and I moved closer to each other. Lawton sat off to the side as I pressed myself against his wife, my arm around her thin waist. A move or two later, her legs buckled. We fell. I played well the part of a fumbling drunk until Lawton pulled me off of her. An emergency broadcast cut short the pop song blaring from the radio. High-tide had irrevocably reclaimed North Carolina’s Outer Banks. That subdued my lust. There would be no more seaside weekends. There was no more seaside.

Charlotte selects a brick of corpse-pale tofu from the vat. “Lawton,” she says, touches his chin. “Lawton. I’ll get the fish if you get the seaweed.” He nods slowly, almost painfully. “Good,” she says, but her expression and the way she pulls her coat tighter around herself say something different.

“I’m okay,” Lawton said. “I need to start doing things alone.”

“I know,” Charlotte said. Her tentative smile exposes her canines, one of which I know is false. She worries people can tell it’s fake, but what I told her is true: all anyone can ever see is that she’s beautiful in all the ways that matter.

A woman passes me carrying a shriveled ginger root that is well past its prime. When Charlotte first brought me here to shop for groceries, she asked me if I believed in the curative power of ginger. We walked down each aisle in turn, and somewhere between the quail eggs and the pickled mango, she explained that Lawton had moon sickness, and would be in the sanitarium for at least the summer, maybe longer. My writer’s heart jumped. The workshop had accustomed me to knowing how stories would go, and I believed this would be no different.

All summer I waited, craving Charlotte. Waited, and listened to her nervous recitation of the latest celebs to go moon sick. Waited, and let her cry in my arms when Lawton’s doctors reported his attempted suicide. Waited, and watched her jump around, giddy and intoxicatingly female, when the President announced his (false) assurances that he would avert the moon crisis. Waited, but Charlotte never chose me.

Lawton was released from the sanatorium, and I was invited over to a welcome-home dinner and movie. He was strange and uncommunicative. Empty. Yet Charlotte nestled next to him during the movie, leaving me to cry alone. I blamed the movie, which had a sad ending. Awash in the flood of their togetherness, I was a spillway and a saint.

I slink from my hiding spot behind the stacked peppers. I will surprise Charlotte at the fish counter while she’s alone. I stop at the end of the aisle that used to overflow with wakame, nori, and kelp. Lawton is close enough that I could say his name and he would hear, but he’s staring at the empty shelves with an expression of horror. I stick my tongue out at him, waggling it indecently, but it

is pointless; he has no idea I am here. I pass the dairy cooler. It is turned off; there’s no need to chill shelf-stable milk. All that weird milk is a reminder that time is running out, and I hurry, but the store elongates, rushing away with the seafood counter where the fish are stretched on ice, their organs and eyes and their last thoughts intact. I strain towards the wisps of fish thought, prepared to tell Charlotte the truth she must to hear. I imagine that she will cry, that the fish will swim in her tears. Her mouth will open, not to breathe, but for my tongue to intertwine with hers like wriggling, finless eels.

It’s an upstream struggle to the fish counter. I stumble near, breathing hard. A wizened man in a knit cap faces me. “We split last fish, me and girl. No share.” There is only one large fish available, and a handful of gray scallops.

“Fisk?” Charlotte says, backing up against the counter.

“This isn’t the first night of workshop,” I say, smiling the jester smile she once said was cute. “You know my given name. Although it was going a bit too far to get a restraining order to prove that to me.”

“You want fish, share with girl,” the old man says.

“Go away, Fisk,” Charlotte says.

“We need to talk.”

“No.”

“I