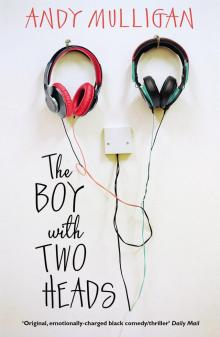

The Boy with Two Heads

Andy Mulligan

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Part One: Newcomer

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Part Two: Treatment

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Part Three: The Chance to be Normal

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Four: Flight

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Five: Survival

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Andy Mulligan

Sneak Preview

Copyright

About the Book

Who says two heads are better than one?

How would you feel if you woke up to find another head growing out of your neck? It knows all your darkest thoughts and it’s not afraid to say what it thinks . . . to ANYBODY.

That’s what happens to eleven-year-old Richard Westlake, and his life becomes very, very complicated.

Part thriller, part horror story, part comedy – this is one of the most riveting novels about fear and friendship that you will ever read.

To Madeleine

PART ONE

NEWCOMER

CHAPTER ONE

Richard Westlake awoke, after a night of unquiet dreams, to discover a lump in his throat. It was no ordinary lump, for he could hardly breathe, and when his mother came to rouse him for school it was obvious that he was in no condition to get up. His voice was husky, and he was sweating.

The doctor arrived. ‘Probably one of those fevers,’ he said. ‘But I have to say, I don’t like the look of the swelling, and you can’t be too cautious.’

He touched it gently with a finger, and the boy winced.

‘Rather tender, is it, young man?’

‘Mmm,’ said Richard.

‘It’s got a rough edge, hasn’t it? Right by the windpipe. I think we’d better get you checked up on.’

‘But it’s . . . football,’ whispered Richard. ‘I can’t miss . . .’ He had to stop, because the words wouldn’t come.

‘You can’t go to school in this condition,’ said the doctor. ‘Football or not, a lump in the throat at your age needs to be taken seriously. Let me make a call.’

‘He seemed all right last night,’ said Mrs Westlake. ‘We were packing his bag together—’

‘I don’t want any delay on this,’ interrupted the doctor. He put his thumb gently under the swelling. ‘I can feel it moving. Yes – I think we’ll get you an ambulance.’

So it was that fifteen minutes later, Richard found himself speeding through the city suburbs, siren blaring. His mother was holding his hand and there was an oxygen mask over his face. He was whisked along corridors and an elevator took him down to neuropathology. Within minutes he was in a tube that bleeped and buzzed. A number of levers held his head absolutely still while a dozen eyes stared down at him.

‘You say he was all right last night?’ said the consultant. He was a large man, with enormous glasses. They made his eyes bulge, and he had the unsettling habit of hardly blinking.

‘He was fine,’ said Mrs Westlake.

‘Happy as Larry,’ said her husband. ‘Out in the garden, running around.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes.’

A door opened, and a nurse entered with a ream of papers. The consultant set them on a desk next to a file full of photographs. The door closed, and Mr Westlake sat beside his wife, grim-faced. He’d come straight from his office and his suit was crumpled.

‘We’re pulling the threads together,’ said the consultant.

‘What threads?’ said Mr Westlake. ‘He’s a healthy boy – always has been. He was doing his homework as usual. A . . . vocabulary test, I think. We watched a bit of television, and then it was cocoa, and off to bed . . . what’s gone wrong?’

‘What is it, Doctor?’ said Mrs Westlake. ‘Why’s everyone being so secretive?’

‘Nobody’s being secretive, my dear.’

‘Mysterious, then!’

‘Where is he now?’ asked Mr Westlake. ‘Why can’t we see him?’

‘A few final tests—’

‘Tests for what, though? Please!’

‘We have to explore all possible avenues at the moment. Believe me, your son’s getting the very best attention.’

‘Can I introduce myself?’ said a man from the corner of the room. He had been sitting in the shadows, observing, with his head on one side. He leaned into the light and smiled. ‘I’m Doctor Warren.’

‘Doctor Warren?’ said Mr Westlake.

‘And I understand exactly how you feel.’

‘Do you?’

‘This is a trying time, for everyone. It’s an unsettling period—’

‘All we want to know is what you’ve found.’

‘Of course.’

He smiled again, and a zip of even teeth appeared above a neatly trimmed beard. ‘I’m an associate psychiatrist here. I look at things from a purely psychiatric perspective. You’ve heard of the Rechner Institute?’

‘Never.’

‘We’re a few miles out of town, specializing in neuroscience. We’re always keen to assist with cases of this kind. Unusual cases—’

‘Look,’ said Mr Westlake more firmly, ‘we just want to know what our son’s got on his neck.’

‘Then we must work together,’ said Dr Warren. ‘What’s he had on his mind lately?’

‘Nothing,’ said Mr Westlake.

‘No? No worries to speak of?’

Mrs Westlake put a hand on her husband’s arm. ‘Nothing major,’ she said. ‘He’s not a worrier, as far as we know. I mean, he’s no different from any other boy. He’s got things on his mind, of course he has. His exams are coming up—’

‘Important ones?’

‘Yes, they’re for the grammar school.’

‘He’s cheerful enough, though,’ said Mr Westlake. ‘Cheerful and normal.’

‘They always are,’ said Dr Warren, nodding. ‘They always seem to be, anyway. I find that children of Richard’s age can have a lot more going on in the old brainbox than we give them credit for. Tell me about his emotional balance.’

‘Oh, for goodness’ sake,’ said Mr Westlake. He stood up and walked to the window. ‘What are you driving at, Doctor? Because I have to confess I don’t have much patience with this kind of thing.’

‘No?’

‘No.’

‘You’d describe your family as emotionally stable?’

‘Yes. I would.’

‘Communication good?’

‘Extremely.’

‘Disappointments? Trauma of any kind?’

Both parents were silent.

‘There was Grandad, of course,’ said Mrs Westlake, at last.

‘But that was . . . that was nearly a year ago, so I can’t see that’s relevant. We lived with my father, and he passed on – he’d been poorly a while, and Richard was with him when it happened. It was . . . well, we talked and talked about it, and he’s a sensible lad—’

‘Any counselling?’

‘No.’

‘Pity.’

Mr Westlake closed his eyes. ‘Like my wife just told you,’ he said, ‘we talked it through at home – all three of us. It was a terrible thing, but Richard’s a sensible lad, and everything got back to normal. He misses him – of course he does. They were close. But he puts his heart into school, as his grandad always encouraged him to . . . he’s trying for one of the scholarships, you see. His friends rallied round and the boy got over it – like the rest of us.’

Dr Warren nodded wisely. ‘How old was Grandad?’

‘What?’

‘Seventy-eight,’ said Mrs Westlake.

‘Right.’

‘All we want to know,’ said Mr Westlake, slowly, ‘is what’s wrong with our son. It’s the neck we’re worried about – not his mind! And you must have some idea, or you wouldn’t be asking all these questions.’

The consultant stood up. ‘Give us a little more time,’ he said. ‘We’re talking to the whole team, and—’

‘Is the lump getting bigger?’ said Mr Westlake.

‘Yes.’

‘How big is it now?’

‘It’s grown considerably,’ said the consultant. ‘The speed of the growth is a major part of the problem, and Doctor Summersby—’

‘Burst it, then!’

‘Sir?’

‘That’s what we used to do. If it’s a boil, or a . . . growth of some kind, you get a needle and—’

‘Oh, it’s not a boil,’ said Dr Warren. ‘We’ve taken X-rays from every conceivable angle; scans as well.’

‘And you still don’t know what it is?’ cried Mrs Westlake. ‘How can that be?’

There was a silence.

‘We know a few things,’ said the consultant quietly. He pulled the papers towards him and unfolded a chart. ‘It’s why I called the Rechner Institute. Doctor Warren here has been analysing the cranial data, so we are moving forward. It’s a rare condition, as I said – but not unknown. Summersby’s a neurological surgeon, based in New Zealand – she’s looking at the results right now, because if we’re right . . .’

The door opened again. A nurse appeared with another computer print-out, this one trailing to the floor. She was white-faced, and nodded once.

‘Confirmation,’ she said. ‘Really?’

‘Yes. The surgeon’s with us by satellite – she’s positive. She’d like to see the parents. At once, if you can.’

They moved to an office. A laptop stood open on the desk, and two speakers were connected. On the screen was the head and shoulders of a serious-looking woman, with hair drawn tightly back from a thin face.

‘That’s Summersby,’ said the consultant. ‘She’s at the cutting edge of neural science, and she’s been observing Richard through monitors.’

‘Can you hear me?’ she said. She tapped at the microphone.

‘Yes,’ said Mr Westlake. He mopped his face with a handkerchief.

‘I’m sorry I’m not with you in person.’ She leaned forward and licked her lips. Two large nostrils seemed to sniff at the screen before she moved backwards and blinked. ‘You must prepare yourselves, Mr and Mrs, er . . . Westlake. You have access to the counselling facility?’

‘I’m right here, Gillian,’ said Dr Warren. ‘We’re standing by.’

‘Good.’

‘What’s wrong?’ said Mrs Westlake, more frightened than ever. ‘They’ve been testing him for hours. Can you tell us what’s wrong?’

‘I’ve seen all the results, Mrs, ah . . . Westlake – and the best thing I can do is explain the situation from a medical point of view. Your son’s at a developmental stage, experiencing what we call a larcedontal extrusion, traumatic or spontaneous. It’s a remarkable thing: your child has the cartilage, and the bone, of a respiratory organ, and that organ’s ancillary to existing tissue – that’s obvious. Now, as you know – as you’ve seen – it’s located in his trachea, but what we’ve established is that it’s outreaching the oesophagus, so we’ve got advanced compound cell division now. If you have any knowledge of basic physiognomy—’

‘Stop,’ said Mr Westlake. ‘Stop.’

There was a silence. Dr Summersby came closer again, and stared. ‘Can’t you hear me?’ she said.

‘Yes!’

‘You said you were going to explain,’ said Mrs Westlake. ‘I don’t understand a word you’re saying.’

‘Well, as I said, medical clarity’s essential in these cases,’ said Dr Summersby. ‘In a case of exponential cellular growth, where the brain—’

‘We don’t understand you,’ cried Mr Westlake. ‘You’re going to have to speak in English.’

The doctor licked her lips again, and removed her spectacles. ‘OK,’ she said. ‘I’ll try again. Your son – Richard – has been developing, for some time, it would seem . . . a second . . . nose. The nostrils, as it were, are connected to the same airway as the existing one – and that’s the main reason he’s been having breathing problems. I want more time to observe, and I’ll be over to examine him, as soon as I can. But I can tell you already that this . . . second organ is sharing your son’s lungs, or trying to. It would also appear to be attached to the embryonic form of a skull, complete with cranium, forehead and jaw.’

‘A head,’ said Mrs Westlake.

There was another silence.

‘What are you saying?’ shouted Mr Westlake. ‘What exactly are you saying? I’m still not clear.’

Dr Summersby blinked, but she held their gaze. ‘I’ve seen a number of these cases, sir – rare as they are. I’m off to Vietnam tomorrow, to look at something similar. Your son is having the most extraordinary cerebral crisis. He’s developing a second head. Yes. And it will emerge in the next twenty-four hours.’

CHAPTER TWO

Richard was unconscious.

The lump had grown significantly. It had gone past the walnut stage, and was now the size of a fist. Sticking up out of the lump was a sharp triangle of flesh, and above that were two red pimples.

‘You can see it, can’t you?’ said the consultant quietly. He put a fat finger under Richard’s chin. ‘That’s the danger-zone, there,’ he said.

Mr and Mrs Westlake simply stared.

‘Summersby’s the expert. She’s encountered similar cases before, but they’ve been hushed up – research has been terribly difficult. There’s one she’s been working on in Asia, which is attracting quite a lot of attention . . . but this is a rare condition.’

‘And you can’t just remove it?’ whispered Mr Westlake.

‘Oh, no,’ said Dr Warren. ‘Not yet. The heads share a brain stem. Same blood supply, so it would be fatal to amputate.’

‘Then . . . what can you do?’

‘We leave things be.’

‘But surely you can deal with it in some way?’ said Mrs Westlake. ‘You can’t just sit back and do nothing!’

‘At the moment we observe.’

‘Listen,’ whispered Mr Westlake. His voice was trembling. ‘You’re telling us that our son now has a twin?’

‘No, sir,’ said the consultant.

‘What, then – a parasite, feeding off him?’

Dr Warren shook his head. ‘No, Mr Westlake. I need to emphasize this: as far as we’re concerned, the second head will be Richard as well. A part of your boy, and we have to be ready for that.’

‘So . . .’ Mr Westlake paused. ‘Oh, I’m lost,’ he said. ‘This is a nightmare . . .’

His wife took over, forcing herself to be calm. ‘You’re telling us that the second head will be . . . functioning, aren’t you? That was the word you used. The new one – it will be able to think? It will have a brain – a mind of its own?’

> ‘For sure.’

‘It will have eyes? It will be able to see?’

A nurse leaned in. ‘I think one’s opening at the moment, Doctor. There’s a growth-spurt, you can see from the monitor.’

Sure enough, the machine by the bed had started to bleep quietly, and a flashing light turned from green to red. The parents stared, and the right-hand pimple burst gently, the crater opening to reveal a tiny eyeball.

‘Oh, Lord,’ said Mrs Westlake. ‘This isn’t possible.’

‘It won’t speak, will it?’ said her husband. His voice was faint, and he held his son’s hand gently. ‘I mean, that’s not possible, surely—’

‘Both heads will speak,’ said the consultant.

‘In fact speech may be quite a feature,’ said Dr Warren. ‘The second tongue is well developed. Disproportionately large, in fact, so I would hope it’s going to be quite a little communicator. We could all learn a very great deal.’

‘It will feel things, then? It will have . . . emotions?’

‘Yes. Absolutely.’

‘How?’

‘Well,’ said the consultant. ‘We don’t understand the phenomenon as well as we’d like. But we suspect it’s rooted in trauma. Latent trauma – buried and repressed.’

Dr Warren leaned forward. ‘What we do know is that you’re looking at an extra dimension of your son, Mr Westlake. The second head will share many of the likes and dislikes you’re familiar with. It’ll have Richard’s memory, or parts of it – the memory’s likely to be quite selective, depending on what’s being ignored. You’ll find that different things come to the surface at different times, so I’ll need to work hard. What will be interesting is to see how the separate brains align themselves. Richard will need to stay at home for a while, but I would hope things will stabilize quite quickly and normal life will resume.’

‘Normal life?’

‘Yes. He won’t be an invalid.’

‘But . . .’ Mr Westlake looked at his wife. ‘He’s got two heads.’

‘And it’s a rare condition,’ said Dr Warren. ‘Rare, but not unknown, and – as I said – it won’t prevent him leading a totally normal life.’

‘He’s just finishing Year Six!’ cried Mr Westlake. He stood up, and pressed his hands to his eyes. ‘He’s in the last year of primary school, eleven years old! He can’t walk around with two heads on his shoulders, can he? Are you suggesting he goes back to school?’