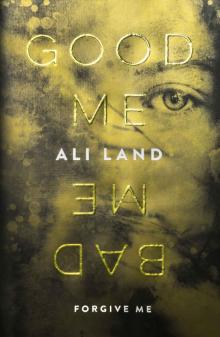

Good Me Bad Me

Ali Land

Ali Land

* * *

GOOD ME BAD ME

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Acknowledgements

Follow Penguin

To mental health nurses everywhere. The true rock stars.

This book is for you.

‘But the hearts of small children are delicate organs. A cruel beginning in this world can twist them into curious shapes.’

Carson McCullers, 1917–1967

Have you ever dreamt of a place far, far away? I have.

A field full of poppies.

Tiny red dancers, waltzing in glee.

Pointing their petals to a path that leads to a shoreline, clean. Unbroken.

Floating on my back, a turquoise ocean. Blue sky.

Nothing. Nobody.

I long to hear the words: ‘I’ll never let anything happen to you.’ Or: ‘It wasn’t her fault, she was only a child.’

Yes, these are the kinds of dreams I have.

I don’t know what’s going to happen to me. I’m scared. Different. I wasn’t given a choice.

I promise this.

I promise to be the best I can be.

I promise to try.

Up eight. Up another four.

The door on the right.

The playground.

That’s what she called it.

Where the games were evil, and there was only ever one winner.

When it wasn’t my turn, she made me watch.

A peephole in the wall.

Asked me afterwards. What did you see, Annie?

What did you see?

1

Forgive me when I tell you it was me.

It was me that told.

The detective. A kindly man, belly full and round. Disbelief at first. Then, the stained dungarees I pulled from my bag. Tiny.

The teddy bear on the front peppered red with blood. I could have brought more, so many to choose from. She never knew I kept them.

Shifted in his chair he did. Sat up straight, him and his gut.

His hand – I noticed a slight tremor as it reached for the telephone. Come now, he said. You need to hear this. The silent waiting for his superior to arrive. Bearable for me. Less so for him. A hundred questions beat a drum in his head. Is she telling the truth? Can’t be. That many? Dead? Surely not.

I told the story again. And again. Same story. Different faces watched, different ears listened. I told them everything.

Well.

Almost everything.

The video recorder on, a gentle whirring the only noise in the room once I finished my statement.

You might have to go to court, you know that, right? You’re the only witness, one of the detectives said. Another asked, do you think it’s safe for us to send her home? If what she’s saying is true? The chief inspector in charge replied, we’ll have a team assembled in a matter of hours, then turned to me and said, nothing’s going to happen to you. It already has, I wanted to reply.

Everything moved quickly after that, it had to. I was dropped off at the school gates, in an unmarked car, in time for pick-up. In time for her to pick me up. She would be waiting with her demands, recently more urgent than usual. Two in the last six months. Two little boys. Gone.

Act normal, they said. Go home. We’re coming for her. Tonight.

The slow grind of the clock above my wardrobe. Tick. Tock. Tick. And they did. They came. The middle of the night, the element of surprise in their favour. A nearly imperceptible crunching on the gravel outside, I was downstairs by the time they forced their way through the door.

Shouting. A tall, thin man dressed in plain clothes, unlike the others. A string of commands sliced through the sour air of our living room. You, take upstairs. You, in there. You two take the cellar. You. You. You.

A tidal wave of blue uniforms scattered throughout our house. Guns held in praying hands, flat against their chests. The thrill of the search, along with the terror of the truth, etched in equal measure on their faces.

And then you.

Dragged from your room. A red crease of sleep visible down your cheek, eyes foggy with the adjustment from a state of rest to a state of arrest. You said nothing. Even when your face was mashed into the carpet, your rights read out, their knees and elbows pressed in your back. Your nightie rode high up your thighs. No underwear. The indignity of it all.

You turned your head to the side. Faced me. Your eyes never left mine, I read them with ease. You said nothing to them, yet everything to me. I nodded.

But only when no one was watching.

2

New name. New family.

Shiny.

New.

Me.

My foster dad Mike’s a psychologist, an expert in trauma; so is his daughter, Phoebe, although more in the causing than the healing. Saskia, the mother. I think she’s trying to make me feel at home, although I’m not sure, she’s very different from you, Mummy. Skinny and vacant.

Lucky, the staff at the unit told me while I waited for Mike to come. What a fantastic family the Newmonts are, and a place at Wetherbridge. Wow. Wow. WOW. Yes, I get it. I should feel lucky, but really I’m scared. Scared of finding out who and what I might be.

Scared of them finding out, too.

A week ago now Mike came to collect me, towards the end of the summer holidays. My hair brushed neat, pulled back in a band, I practised how to speak, should I sit or stand. Every minute that went by, when the voices I heard weren’t his, the nurses instead, sharing a joke, I became convinced he and his family had changed their minds. Come to their senses. I stood rooted to the spot, waiting to be told, sorry, you won’t be going anywhere today.

But then he arrived. Greeted me with a smile, a firm handshake, not formal, but nice, nice to know he wasn’t afraid to connect. To run the risk of being contaminated. I remember him noticing my lack of belongings, one small suitcase. In it, a few books, some clothes and other things hidden too, memories of you. Of us. The rest, taken as evidence when our house was stripped bare. Not to worry, he said, we’ll organize a shopping trip. Saskia and Phoebe are at home, he added, we’ll all have dinner together, a real welcome.

We met with the head of the unit. Gently, gently, he said, take each day as it comes. I wanted to tell him, it’s the nights I fear.

Smiles exchanged. Handshakes. Mike signed on the line, turned to face me and said, ready?

Not really, no.

But I left with him anyway.

The drive home was short, less than an hour. Every street and building new to me. It was light when we got there, a big house, white pillars at the front. Okay? asked Mike. I nodded, though I didn’t feel okay. I waited for him to unlock the front door; my heart

spiralled up into my throat when I realized it wasn’t locked. We walked straight in, could have been anyone. He called out to his wife, I’d met her a few times now. Sas, he said, we’re home. Coming, was the reply. Hi, Milly, she said, welcome. I smiled, that’s what I thought I should do. Rosie, their terrier, greeted me too, jumped at my legs, sneezed with joy when I reached for her ears, gave them a rub. Where’s Phoebs? Mike asked. On her way back from Clondine’s, Saskia replied. Perfect, he said, dinner in half an hour or so then. He suggested Saskia should show me to my room, I remember him nodding at her in a way that looked like encouragement. For her, not me.

I followed her up the stairs, tried not to count. New home. New me.

It’s just you and Phoebe on the third floor, Saskia explained, we’re on the next level down. We’ve given you the room at the back, it has a nice view of the garden from the balcony.

It was the yellow of the sunflowers I saw first. Brightly coloured. Smiles in a vase. I thanked her, told her they were one of my favourite flowers, she looked pleased. Feel free to explore, she said, there’s some clothes in the wardrobe, we’ll get you more of course, you can choose them. She asked me if I needed anything, no, I replied, and she left.

I put my suitcase down, walked over to the balcony door, checked it was locked. Secure. The wardrobe to the right, tall, antique pine. I didn’t look inside, I didn’t want to think about putting on clothes, taking them off. As I turned round, I noticed drawers under the bed, opened them, ran my hands along the back and the sides – nothing there. Safe, for now. An en suite, large, the entire wall on the right covered with a mirror. I turned away from my reflection, didn’t want to be reminded. I checked the lock on the bathroom door worked, and that it couldn’t be opened from the outside, then I sat on the bed and tried not to think about you.

Before long, I heard feet pounding up the stairs. I tried to stay calm, to remember the breathing exercises I’d been shown by my psychologist, but my head felt fuzzy, so when she appeared at my door I focused on her forehead, as close to eye contact as I could manage. Dinner’s ready, her voice more like a purr, creamy, a dash of snide, just as I remembered her from when we met with the social worker. We couldn’t meet at the unit, she wasn’t allowed to know the truth, or be given the opportunity to wonder. I remember feeling intimidated. The way she looked, blonde and self-assured, bored, forced to welcome strangers into her home. Twice during the meeting she asked how long I’d be staying. Twice she was shushed.

Dad asked me to come and get you, she said, her arms folded across her chest. Defensive. I’d seen the staff at the unit calling patients out on what their body language meant, labelling it. I quietly watched, learnt a lot. It’s days ago now, but the last thing she said before she turned on her heels like an angry ballerina stuck in my head: Oh, and welcome to the mad house.

I followed her smell, sweet and pink, down to the kitchen, fantasizing about what having a sister might be like. What sort of sisters she and I might become. She would be Meg, I thought, I would be Jo, little women of our own. I’d been told at the unit, hope was my best weapon, it would be what got me through.

Foolishly, I believed them.

3

I slept in my clothes that first night. Silk pyjamas chosen by Saskia remained unworn, touched only to move them from my bed. The material slippery on my skin. I’m able to sleep better now, if only for part of the night. I’ve come a long way since I left you. The staff at the unit told me I didn’t speak for the first three days. I sat on the bed, back against the wall. Stared. Silent. Shock they called it. Something much worse, I wanted to say. Something that came into my room every time I allowed myself to sleep. Moved in a slither, under the door, hissed at me, called itself Mummy. Still does.

When I can’t sleep, it’s not sheep I count, it’s days until the trial. Me against you. Everybody against you. Twelve weeks on Monday. Eighty-eight days, and counting. I count up, I count down. I count until I cry, and again until I stop, and I know it’s wrong but, somewhere in the numbers, I begin to miss you. I’m going to have to work hard between now and then. There are things I must put right in my head. Things I must get right if I’m called upon to present in court. So much can go wrong when all eyes are looking the same way.

Mike has a big part to play in the work to be done. A treatment plan drawn up between him and the unit staff detailed a weekly therapy session with me in the run-up to the trial. An opportunity for me to discuss any concerns or worries with him. Yesterday he suggested Wednesdays, midway through each week. I said yes, not because I wanted to. But because he wanted me to, he thinks it will help.

School begins tomorrow, we’re all in the kitchen. Phoebe’s saying thank god, can’t wait to get back, and out of this house. Mike laughs it off, Saskia looks sad. Over the past week I’ve noticed something’s not right between her and Phoebe. They exist almost entirely independently of each other, Mike the translator, the mediator. Sometimes Phoebe calls her Saskia, not Mum. I expected her to be punished the first time I heard her say it, but no. Not that I’ve seen. I also haven’t seen them touch each other, and I think touch is an indicator of love. Not the kind of touch you experienced though, Milly. There is good touch and bad touch, said the staff at the unit.

Phoebe announces she’s going out to meet someone called Izzy, who just got back from France. Mike suggests she take me too, introduce me. She rolls her eyes and says come on, I haven’t seen Iz all summer, she can meet her tomorrow. It’ll be nice for Milly to meet one of the girls, he persists, take her to some of the places you hang out. Fine, she agrees, but it’s not really my job.

‘It’s nice of you though,’ says Saskia.

She stares her mother down. Stares and stares, until she wins. Saskia looks away, a pink flush imprinting on her cheeks.

‘I was just saying how nice I thought you were being.’

‘Yeah, well, nobody asked you, did they?’

I wait for the backlash, a hand or an object. But nothing. Only Mike.

‘Please don’t speak to your mother like that.’

When we leave the house there’s a girl in a tracksuit sitting on the wall opposite our driveway, she looks at us as we pass. Phoebe says fuck off you little shit, find another wall to sit on. The girl responds by giving her the finger.

‘Who was that?’ I ask.

‘Just some skanky kid from the estate.’

She nods towards the tower blocks on the left-hand side of our road.

‘Don’t get used to this by the way, I’ll be doing my own thing when school kicks off properly.’

‘Okay.’

‘The close just there runs right past our garden, there’s nothing much up there, a few garages and stuff, and it’s quicker to get to school this way.’

‘What time do you normally leave in the morning?’

‘It depends. I usually meet Iz and we walk together. Sometimes we go to Starbucks and hang out for a bit, but it’s hockey season this term and I’m captain so I’ll be leaving early most mornings doing fitness and stuff.’

‘You must be really good if you’re captain.’

‘Suppose so. So what’s your story then? Where are your folks?’

An invisible hand reaches into the pit of my stomach, squeezes it hard, doesn’t let go. I feel my head fill up again. Relax, I tell myself, I practised these questions with the staff at the unit, over and over again.

‘My mum left when I was young, I lived with my dad but he died recently.’

‘Fuck, that’s pretty shit.’

I nod, leave it at that. Less is more, I was told.

‘Dad probably showed you some of this stuff last week but at the end of our road, just here, there’s a short-cut to school that way.’

She points to the right.

‘Cross over the road, take the first left and then the second street on the right, it takes about five minutes from there.’

I’m about to thank her but she’s distracted, her face breaking into a smile. I f

ollow her gaze and see a blonde girl crossing the road towards us, blowing exaggerated air kisses. Phoebe laughs and waves, says, that’s Iz. Her legs glow brown against the ripped denim shorts she’s wearing, and like Phoebe, she’s pretty. Very pretty. I watch the way they greet each other, drape round each other, a conversation begins a hundred miles an hour. Questions are flung, returned, they pull their phones out of their pockets, compare photos. They snigger about boys, and a girl named Jacinta who Izzy says is an absolute fright in her bikini, I swear the whole fucking pool emptied when she went for a swim. This whole interaction takes only minutes, but with the awkwardness of being ignored, it feels like hours. It’s Izzy who looks at me, then says to Phoebe, ‘Who’s this then, the newest newbie at Mike’s rescue centre?’

Phoebe laughs and replies, ‘She’s called Milly. She’s staying with us for a bit.’

‘Thought your dad wasn’t taking anyone else in?’

‘Whatever. You know he can’t help himself when it comes to strays.’

‘Are you coming to Wetherbridge?’ Izzy asks me.

‘Yes.’

‘Are you from London?’

‘No.’

‘Do you have a boyfriend?’

‘No.’

‘Crikey, do you only speak in robot tongue? Yes. No. No.’ She waves her arms around, makes a mechanical noise like the Dalek from the Doctor Who episode I watched in a drama lesson at my old school. They both erupt into laughter, return to their phones. I wish I could tell them I speak like that, slow and purposeful, when I’m nervous and to filter the noise. White noise, punctuated by your voice. Even now, especially now, you’re here, in my head. Normal behaviour required little effort for you, but for me, an avalanche. I was always surprised by how much they loved you at your work. No violence or rage, your smile gentle, your voice soothing. In the palm of your hand you kept them, isolated them. Took the women you knew could be persuaded to one side, talked close in their ears. Secure. Loved. That’s how you made them feel, that’s why they trusted you with their children.