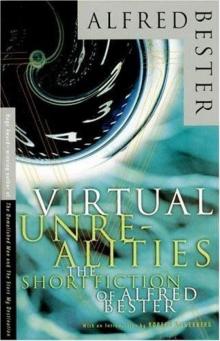

Virtual Unrealities: The Short Fiction of Alfred Bester

Alfred Bester

ALFRED BESTER

VIRTUAL

UNREALITIES

Alfred Bester was born in New York in 1913. After attending the University of Pennsylvania, he sold several short stories to Thrilling Wonder Stories in the early 1940s. He then embarked on a career as a scripter for comics, radio, and television, where he worked on such classic characters as Superman, Batman, Nick Carter, Charlie Chan, Tom Corbett, and the Shadow. In the 1950s, he returned to prose, publishing several short stories and two brilliant, seminal novels, The Demolished Man (which was the first winner of the Hugo Award for Best Novel) and The Stars My Destination. In the late 1950s, he wrote travel articles for Holiday magazine, and eventually became their Senior Literary Editor, keeping the position until the magazine folded in the 1970s. In 1974, he once again came back to writing science fiction with the novels The Computer Connection, Golem100, and The Deceivers, and numerous short stories. After being a New Yorker all his life, he died in Pennsylvania in 1987, but not before he was honored by the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America with a Grandmaster Award.

BOOKS BY

ALFRED BESTER

The Stars My Destination

The Demolished Man

Virtual Unrealities: The Short Fiction of Alfred Bester

COMING SOON :

Psychoshop (with Roger Zelazny)

Virtual Unrealities

The Short Fiction of Alfred Bester

Introduction by Robert Silverberg

Stories selected by Robert Silverberg, Byron Preiss, and Keith R. A. Decandido

A Byron Preiss Book

ibooks

Habent Sua Fata Libelli

“And 3 ½ to Go” and “The Devil Without Glasses” copyright © 1997 by the Estate of Alfred Bester, Joe Suder, and Kirby McCauley

Compilation copyright © 1997 by the Estate of Alfred Bester, Joe Suder, and Kibby McCauley

Introduction © 1997 by Agberg, Ltd.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

A Byron Preiss Visual Publication, Inc. Book.

Special thanks to Kirby McCauley, J. Edward Kastenmeier, Martin Asher, Carol D. Page, and Minsun Pak

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Date

Bester, Alfred.

Virtual unrealities: the short fiction of Alfred Bester / introduction by Robert Silverberg; stories selected by Robert Silverberg, Byron Preiss, and Keith R. A. DeCandido.

p. cm

“A Byron Preiss book.”

ISBN 0-679-76783-5

I. Silverberg, Robert. II. Preiss, Byron. III. DeCandido, Keith R. A. IV. Title.

PS3552.E796V57 1997

813’.54—dc21 97-8738 CIP

Book design by Iris Weinstein

ibooks website: http://www.ibooksinc.com

J. Boylston & Company, Publishers

1230 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10128

[email protected]

CONTENTS

Introduction by Robert Silverberg

Disappearing Act

Oddy and Id

Star Light, Star Bright

5,271,009

Fondly Fahrenheit

Hobson’s Choice

Of Time and Third Avenue

Time Is the Traitor

The Men Who Murdered Mohammed

The Pi Man

They Don’t Make Life Like They Used To

Will You Wait?

The Flowered Thundermug

Adam and No Eve

And 3½ to Go (fragment)

Galatea Galante

The Devil Without Glasses (previously unpublished)

INTRODUCTION

Robert Silverberg

Alfred Bester was a winner right from the start—quite literally. His very first story (“The Broken Axiom,” Thrilling Wonder Stories, April 1939) carried off that month’s $50 prize in the Amateur Story Contest that Thrilling Wonder was then running every issue to attract new talent. He was twenty-five years old, a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania (where he majored, he liked to say, “in music, physiology, art, and psychology”), and was working at the time as a public relations man while pondering the challenges of a career as a writer.

“The Broken Axiom” isn’t a marvelous story, which is one of several reasons why it hasn’t been included in this collection. It is, in fact, a creaky and pretty silly item full of pseudoscientific gobbledygook and cardboard characters, which Bester himself spoke of later as “rotten.” But silly gobbledygooky stories were something that the garishly pulpy old Thrilling Wonder Stories published by the dozens in those days, and this initial contribution by the novice Bester was well up there in professionalism with the rest of that issue’s copy, all of which was the work of veteran pros.

And observe, if you will, the magnificent cockeyed pizazz and breathtaking narrative thrust with which Bester gets his first story in motion, back there nearly sixty years ago:

It was a fairly simple apparatus, considering what it could do. A Coolidge tube modified to my own use, a large Radley force-magnet, an atomic pick-up, and an operating table. This, the duplicate set on the other side of the room, plus a vacuum tube some ten feet long by three inches in diameter, were all that I needed.

Graham was rather dumfounded when I showed it to him. He stared at the twin mechanism and the silvered tube swung overhead and then turned and looked blankly at me.

“This is all?” he asked.

“Yes,” I smiled. “It’s about as simple as the incandescent electric lamp, and I think as amazing.”

And with that he was off and running on a literary career that was a lot less simple than the incandescent electric lamp, and just about as amazing.

For the next forty-odd years, this dynamic and formidably charismatic man blazed a bewildering zigzag trail across the world of science fiction. But that was only a part-time amusement for him; he also wrote plays, the libretto for an opera, radio scripts, comic-book continuity, television scripts, travel essays, and a million other things. Every now and then the desire to write science fiction came over him, though, like a sort of fit, and he let it have its way. And thus he gave us two of the most astonishing science fiction novels ever written (The Demolished Man and The Stars My Destination) and, intermittently over the decades, a couple of dozen flamboyant and extraordinary short stories, stories that are like none ever written by anyone else, stories that leave the reader dizzy with amazement.

When Bester was at the top of his form, he was utterly inimitable; when he missed his mark, he usually missed it by five or six parsecs. But he was always flabbergasting. This is how the critic Damon Knight put it in a 1957 essay:

Dazzlement and enchantment are Bester’s methods. His stories never stand still a moment; they’re forever tilting into motion, veering, doubling back, firing off rockets to distract you. The repetition of the key phrase in “Fondly Fahrenheit,” the endless reappearances of Mr. Aquila in “The Star-comber” are offered mockingly: try to grab at them for stability, and you find they mean something new each time. Bester’s science is all wrong, his characters are not characters but funny hats; but you never notice: he fires off a smoke-bomb, climbs a ladder, leaps from a trapeze, plays three bars of “God Save the King,” swallows a sword and dives into three inches of water. Good heavens, what more do you want?

Even those “rotten” early stories of Bester’s display the restless fizz of imagination that is his hallmark. Most of them really are stinkers, objects casually assembled out of handy spare parts to meet

the modest needs of the prewar penny-a-word pulp magazine market. Though there are flashes of pure Besterian magic in every one of them, all but a few stick close to the conventional fiction formulas of the era. But “Adam and No Eve” (Astounding Science Fiction, September 1941) was good enough to get into Adventures in Time and Space, the first of the classic science fiction anthologies, and it still has a great deal to say to today’s readers. And the wild and frantic fantasy novella “Hell is Forever” (Unknown Worlds, August 1942) unleashes the manic power of Bester’s prose in a way that gives a clear clue to the passionate risk taking and experimentation that marks the fiction of his full maturity.

After that first burst of science fiction, though, he took an eight-year hiatus, during which he wrote reams of comic strip continuity—for Superman, Captain Marvel, The Green Lantern, many others, and scripts for such radio shows as Nero Wolfe, Charlie Chan, and The Shadow. When television arrived on the scene after the war, Bester tried his hand at that too, but it was an unhappy experience in which his volcanic drive toward originality of expression put him into violent collision with the powerful commercial forces ruling the new medium. In 1950—36 years old, and entering into his literary maturity—he found himself looking once more toward science fiction.

There had been great changes in the science fiction field during Bester’s eight-year absence, and no need now existed for him to conform to the hackneyed pulp magazine conventions. Before the war, there had been only one editor willing to publish science fiction aimed at intelligent and sophisticated readers—John W. Campbell, the editor of Astounding Science Fiction and its fantasy-fiction companion, Unknown Worlds. In Campbell’s two magazines such first-rank science fiction writers as Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, Theodore Sturgeon, L. Sprague de Camp, and A. E. van Vogt found their natural home. The seven or eight other magazines relied primarily on juvenile tales of fast-paced adventure featuring heroic space captains, villainous space pirates, mad scientists, and glamorous lady journalists.

But that kind of crude action fiction had largely gone out of fashion by 1950, and most of the old science fiction pulps had either folded or upgraded their product. Campbell’s adult and thoughtful Astounding was still in business, though—(Unknown Worlds had vanished during the war, a victim of paper shortages)—and it had been joined by two ambitious newcomers, Fantasy and Science Fiction, edited by the erudite, witty Anthony Boucher, and Galaxy, whose editor was the gifted and ferociously competitive Horace Gold.

Bester began his return to science fiction with a story for Campbell—“Oddy and Id,” which Campbell published under the title of “The Devil’s Invention” in Astounding for August 1950. But the postwar Campbell had become obsessed with Dianetics, a technique of psychotherapy invented by science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard that Bester regarded as quackery—and Bester found the changed atmosphere around the great editor too uncongenial for comfort. He turned instead to the new magazines of Boucher and Gold, and never wrote for Astounding again.

His stories for those magazines, infrequent though they were, had an immediate and explosive effect that moved him swiftly to the forefront of the field. The first was the whimsical little “Of Time and Third Avenue” (Fantasy and Science Fiction, October 1951). Then came the remarkable novel The Demolished Man, which Galaxy serialized in its issues for January, February, and March of 1952. Science fiction had never seen anything remotely like it—a stunningly intricate futuristic detective story coupled with startling applications of elements of Freudian theory and told in a manner rich with Joycean linguistic inventiveness. The book made an overwhelming impact—in 1953 it received the very first Hugo award as best science fiction novel of the year—and has been regarded as a classic ever since.

In the wake The Demolished Man came a steady series of shorter works, all of them brilliant on a smaller scale: “Hobson’s Choice” (Fantasy and Science Fiction, August 1952), “Time is the Traitor” (Fantasy and Science Fiction, September 1953), “Disappearing Act” (Star Science Fiction #2, 1953), “5,271,009” (Fantasy & Science Fiction, March 1954), and the most spectacular one of all, “Fondly Fahrenheit” (Fantasy & Science Fiction, August 1954), a bravura demonstration of literary technique about which an entire textbook could be written.

Despite the wildly enthusiastic response these stories engendered, science fiction never became anything other than a hobby for Alfred Bester: perhaps for the best, for it is hard to see how anyone could have kept up this level of imaginative fertility on a day-by-day basis. His stories, every one a dazzler, appeared every year or two in Fantasy and Science Fiction, and his second novel, the awesome The Stars My Destination, proved to be a fitting companion to The Demolished Man when it appeared in Galaxy in 1956. But he was spending most of his time overseas now, doing travel articles for Holiday magazine and such other slick publications of the time as McCall’s and Show. In the final two decades of his life—he died in 1987 at the age of 73—his work in science fiction was sporadic at best. He did write several late novels and a handful of short stories, and the unmistakable Bester touch is evident in all of them, though they fall short of the formidable achievement of his finest work.

How formidable, actually, was that achievement?

Alfred Bester’s two great novels must rank in almost everyone’s top-ten list of science fiction’s all-time peaks. And his body of short stories puts him, I think, among the two or three finest writers of short science fiction who ever lived. It has been a delight to experience those stories once again in the course of assembling this collection; and if you will be encountering them for the first time as you read this book, I envy you the pleasure.

—Robert Silverberg

Oakland, California

September 1996

DISAPPEARING ACT

This one wasn’t the last war or a war to end war. They called it the War for the American Dream. General Carpenter struck that note and sounded it constantly.

There are fighting generals (vital to an army), political generals (vital to an administration), and public relations generals (vital to a war). General Carpenter was a master of public relations. Forthright and Four-Square, he had ideals as high and as understandable as the mottoes on money. In the mind of America he was the army, the administration, the nation’s shield and sword and stout right arm. His ideal was the American Dream.

“We are not fighting for money, for power, or for world domination,” General Carpenter announced at the Press Association dinner.

“We are fighting solely for the American Dream,” he said to the 162nd Congress.

“Our aim is not aggression or the reduction of nations to slavery,” he said at the West Point Annual Officers’ Dinner.

“We are fighting for the Meaning of Civilization,” he told the San Francis’co Pioneers’ Club.

“We are struggling for the Ideal of Civilization; for Culture, for poetry, for the Only Things Worth Preserving,” he said at the Chicago Wheat Pit Festival.

“This is a war for survival,” he said. “We are not fighting for ourselves, but for our Dreams; for the Better Things in Life which must not disappear from the face of the earth.”

America fought. General Carpenter asked for one hundred million men. The army was given one hundred million men. General Carpenter asked for ten thousand V -Bombs. Ten thousand U-Bombs were delivered and dropped. The enemy also dropped ten thousand U-Bombs and destroyed most of America’s cities.

“We must dig in against the hordes of barbarism,” General Carpenter said. “Give me a thousand engineers.”

One thousand engineers were forthcoming and a hundred cities were dug and hollowed out beneath the rubble.

“Give me five hundred sanitation experts, eight hundred traffic managers, two hundred air-conditioning experts, one hundred city managers, one thousand communication chiefs, seven hundred personnel experts …”

The list of General Carpenter’s demand for technical experts was endless. America did not know how to supply them

.

“We must become a nation of experts,” General Carpenter informed the National Association of American Universities. “Every man and woman must be a specific tool for a specific job, hardened and sharpened by your training and education to win the fight for the American Dream.”

“Our Dream,” General Carpenter said at the Wall Street Bond Drive Breakfast, “is at one with the Greeks of Athens, with the noble Romans of … er … Rome. It is a dream of the Better Things of Life. Of Music and Art and Poetry and Culture. Money is only a weapon to be used in the fight for this dream. Ambition is only a ladder to climb to this dream. Ability is only a tool to shape this dream.”

Wall Street applauded. General Carpenter asked for one hundred and fifty billion dollars, fifteen hundred dedicated dollar-a-year men, three thousand experts in mineralogy, petrology, mass production, chemical warfare, and air-traffic time study. They were delivered. The country was in high gear. General Carpenter had only to press a button and an expert would be delivered.

In March of A.D. 2112 the war came to a climax and the American Dream was resolved, not on any one of the seven fronts where millions of men were locked in bitter combat, not in any of the staff headquarters or any of the capitals of the warring nations, not in any of the production centers spewing forth arms and supplies, but in Ward T of the United States Army Hospital buried three hundred feet below what had once been St. Albans, New York.

Ward T was something of a mystery at St. Albans. Like all army hospitals, St. Albans was organized with specific wards reserved for specific injuries. Right-arm amputees were gathered in one ward; left-arm amputees in another. Radiation burns, head injuries, eviscerations, secondary gamma poisonings, and so on were each assigned their specific location in the hospital organization. The Army Medical Corps had established nineteen classes of combat injury which included every possible kind of damage to brain and tissue. These used up letters A to S. What, then, was in Ward T?