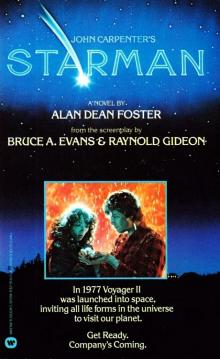

Starman

Alan Dean Foster

THE STRANGER

He came to observe life on earth—that's what happens when a peace-loving alien takes the friendly invitations we send into space seriously. But the U.S. Air Force shot down the starman’s ship, and now he has to clone the body of a human being just to stay alive. Armed with a smattering of earthly lore (how to say hello in Chinese, the Stones “Satisfaction”) collected from Voyager II, as well as his own mind-boggling extraterrestrial powers, he will set off with a beautiful young earth woman on what will become the greatest adventure of their lives—a dangerous flight across America into the unexplored territory of interplanetary love . . .

THE CHILD WAS GROWING EVEN

AS SHE LOOKED AT IT.

It twisted and contorted, whining with the effort it was making. Legs and arms lengthened before her eyes. The torso expanded. Facial features began to crinkle and develop definition. And with each new spurt of growth it threw off a brilliant flash of light.

It was impossible. She stood there, halfway through the doorway, trying to make some sense out of what she was witnessing. She held the back of her right hand against her open mouth and seemed suddenly unable to close her jaws, just as she was unable to tear her gaze away from the thing on the floor of her living room.

It was bigger now, much bigger. In the poor light she couldn’t make out many details, and each flash of light left her half-blinded. The infant was long gone now. In its place a grown man lay twisting and turning on the hardwood floor . . .

And he had Scott’s face.

Also by

Alan Dean Foster

ALIEN

CLASH OF THE TITANS

THE MAN WHO USED THE UNIVERSE

KRULL

OUTLAND

THE I INSIDE

SPELLSINGER

THE HOUR OF THE GATE

THE DAY OF THE DISSONANCE

SHADOWKEEP

Published by

WARNER BOOKS

WARNER BOOKS EDITION

Copyright © 1984 by Columbia Pictures Industries Inc.

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.,

666 Fifth Avenue,

New York, N.Y. 10103

A Warner Communications Company

Printed in the United States of America

First Printing: December, 1984

ISBN 0-446-32598-8

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Books

Title

Copyright

Dedication

STARMAN

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

For Pete Branham—

Who’s better than he thinks

One

Nobody saw the ship.

It came in quietly on little hypergravitic cat feet and didn’t steal silently away. Instead, it assumed an orbit some sixty thousand kilometers out from the surface of the beautiful blue-and-white planet. No notice was taken of it by the inhabitants of the planet below because the crew of the ship did not wish to be noticed. They maintained their anonymity by the simple expedient of diverting any questing impulses around themselves. Devices within the ship were capable of bending gravity waves. Diverting radar was far simpler.

In a special chamber deep within the bowels of the great ship was an Object. They had found the Object drifting forlornly through interstellar space, going nowhere at a ridiculously slow pace. Within its hard metal body the lonely traveler contained primitive visual and aural encodings. It didn’t take the crew long to break down the codes into thousands of bits of comprehensible information. What the translation of those kilobytes of random ramblings said was, more or less, “Hi.” In addition to the greetings there were directions, of a sort.

There was discussion and argument, the outcome of which was a decision to go and see what the builders of the traveler might be about. There was conversation and consultation across parsecs, the result of which was that the ship changed course.

Having completed the journey the ship hovered now above the traveler’s world of origin. From within the crew observed silently, recording and monitoring, taking readings and making measurements. This went on for some time. But no matter how sophisticated the instrumentation, there are some things that cannot be learned from a distance of sixty thousand kilometers. Study from a distance must ultimately give way to intimate examination.

There was never any doubt which of them would take the critical, necessary next step. He was an exceptional individual even among his own kind (we will call him a “he” for the sake of biological expediency). Despite the danger inherent in visiting any primitive world of unknown hazards and potential, his fellow crew-members envied him. There were no protests, however. None argued to go in his stead. The people who crewed the great ship had long since outgrown such absurdities as envy. Each of them knew full well that the one selected to make the drop was by far the best qualified of any of them to do so.

The explorer entered his tiny drop vessel without fanfare. There were no crowds of well-wishers standing by to see him off, and none needed. The rest of the crew was busy attending to their respective tasks. If asked to explain their attitude they would have replied that moments spent on frivolity are moments lost to the triumph of entropy. That was the real enemy, not any rambunctious primitives inhabiting the world below.

Not that they didn’t feel concern for him. Even a brief survey of a backward world entailed certain risks. So there were silent expressions of concern for the explorer’s safety as the hatch opened in the flank of the great ship and the little research craft eased out into space. The crew knew one another well. They were more than a family, and the explorer was one of them. The sooner his task was completed and he was safely back among them, the easier all would rest.

Despite this anxiety they were all anxious to learn the results of the forthcoming survey. They were hopeful as well as nervous. In the vast loneliness of the universe, intelligence was a rare and precious commodity. If the explorer’s survey proved fruitful it would mean that the galaxy would become a little less empty.

Part of the danger to the explorer stemmed from the small size of his vessel. It was designed to travel hither and yon, into difficult to reach places, while attracting a minimum of attention. Because of its smallness it did not have room for the instrumentation that could deflect curious varieties of energy around itself. It would be open to detection from the surface.

Both the explorer and the crew hoped this would not make any difference in his mission. They had reason to be hopeful. The size of the drop craft would make it hard to notice, and the design of the interstellar traveler whose message they had deciphered suggested that the technology of its makers was still quite primitive.

Carmichael leaned back in the chair, turned the magazine sideways to let the centerfold tumble free, and studied the resultant anatomical schematic with considerable interest. His powers of concentration were admirable and he missed nothing. Despite this he felt compelled to review the glossy display several times before refolding it back into the parent magazine. With a sigh he moved on to an article by William E. Buckley, Jr., trying but failing to muster as much enthusiasm for it as he had for the previous pages.

The readout nearby which indicated climatological conditions outside informed him that the temperature was eighty-four and the humidity ridiculously high. Around him it was pleasantly cool. He knew that the air conditioning was there more for the benefit of the machinery he monitored than for himself, but he didn’t mind.

Around him, tons of intricately woven metal formed a gigantic dish that scanned the sky around the

clock. The dish’s job was to search for electronic anomalies. It had been doing its job patiently and without much success for many years now. Carmichael recognized the occasional bleep or squirp that issued from a speaker in front of him. No surprises. They didn’t interrupt his reading. It was good job for a man who liked to read.

And he was good at it. It required a special kind of patience to be able to sit alone in the room perusing centerfold after centerfold without going over the edge and breaking up the furniture.

A telltale buzzed, drawing the attention of one eye to a video monitor set among dozens of others in the wall of instruments. Carmichael frowned to himself, set the acerbic conservative’s opinions aside, and sat up straight in his chair. He was concentrating on the one screen to the exclusion of everything else in the room.

Still there—the anomaly. He got out of the chair and began fine-tuning controls. The anomaly would not go away. If anything, it loomed larger the longer he worked on it. Now not only Buckley but his pneumatic predecessor as well were forgotten. Carmichael felt a sensation not normally attendant upon his job: excitement.

Nearby, a computer printer began machine-gunning information onto paper. He yanked it out of the printer as soon as the hard copy was completed. There it was, in full color. Proof of an impossibility. Scientifically speaking, his ass was covered.

He reached for the special phone.

Matthews and Ford watched the line of little yellow lights come to life on the screen in front of them. The screen was transparent and you could see through it, past the yellow dots and the bright green and red lines the yellow one was crossing. The two men were watching the screen with the intensity of a couple of fifteen year olds at the local video arcade who were down to their last quarter. There were significant differences, however. The screen they were watching cost millions to operate, and the movement of the yellow lights was beyond their control. They were spectators instead of participants.

“This is crazy.” Matthews spoke without turning away from the screen. The growing line of yellow lights had him mesmerized.

“It’s right where Arcebio said it would be.”

“Crazy.” Two more dots came to yellow life, extending the line still further. If the line kept growing it would soon intersect the irregular red line on the left-hand side of the screen. That would be very significant, because the red line indicated the coastline of the state of Washington.

Other men and women glanced over from their positions in front of smaller, console-mounted screens. They badly wanted to join Matthews and Ford but could not leave their own posts. A third figure who was not constrained by such considerations joined the first two in eying the screen. He was short, old, and didn’t have much hair left. Instead of hair, an aura of power clung to him.

“What do you think, gendemen?” he finally asked Matthews and Ford. “Is she Soviet?”

Ford considered. “Possible. North Pacific origin, high-level atmospheric entry, radical angle of descent, and it’s up there all by its lonesome. Maybe they’re probing us with a dud to see if they can slip one through.”

“ICBM?”

Matthews shook his head. “That’s what’s crazy, sir. It’s moving much too slowly. I don’t figure it at all. What’s more, it appears to vary its speed.”

“What about a variable-orbit reconnaissance satellite?”

“If so, it’s full of stuff we’ve never heard of. I’ve never seen anything behave like this before. Weird.”

“I don’t need weird. I need what it is.”

“No can say, sir,” Ford told him.

“But it’s definitely not ours?”

Both men shook their heads. “Not unless some agency’s running one hell of a clever test,” Ford added.

“No, it’s no test,” said their superior. He watched the screen in silence. Another yellow light appeared, crossing the red coastline. That was enough. He turned, crossed to a desk, and picked up a telephone. He didn’t have to dial the number he wanted. The phone had no dial. But everyone in the room watched him anyway. No one spoke.

“Beautiful night, George.” The general was in an ebullient mood and not at all adverse to letting his fellow concert-goers know it.

George Fox, the director of the National Security Agency, smiled back at his friend, took a sip of his martini, and gazed out across the Potomac. There were only five minutes of intermission remaining. He was going to have to hurry the martini if he wanted to finish it. That was a shame, because he was enjoying the relaxed evening. For a change, the world tonight was a relatively peaceful place. The Mozart had soothed him and he was looking forward to the stimulating Janaček to come.

He could simply dispose of the remainder of his drink, but that would be painful. He hated waste. It was one reason why he’d risen as high within the government as he had.

“Yes, it is pretty out,” he agreed. “How’re the kids?”

The general shrugged. “Same. I’m trying to wean Debbie away from M-TV. She’s sixteen.”

The naval flag officer who formed the third member of the triumvirate commiserated with his colleague. “That’s going to be tough. You know, for the price of one guided-missile frigate we could beam the stuff to every household in Russia. End the cold war inside a month.”

“Not a bad idea,” the general admitted. “Think they’d accept Michael Jackson as the new tsar?” Both men laughed quietly. Fox did not. He didn’t laugh much.

The out-of-breath lieutenant finally spotted them standing on the outside promenade, turned toward them. He was trying to move quickly through the crowd without attracting attention.

“Mister Director?”

Fox turned to the newcomer. He betrayed only the slightest hint of the irritation he felt. He had this sinking feeling he wasn’t going to be allowed to enjoy the rest of the concert.

“Yes?” The lieutenant handed him a manila envelope. Fox slipped the seal and studied the message contained within. As was the nature of such communiqués it was brief, to the point, and full of implications. He read it over a second time before slipping it back into the envelope. The two senior military officers standing nearby studiously diverted their attention elsewhere.

The general did his best to sound casual. “Something important, George?”

Fox replied with a thin smile. “I don’t think so, but you know how these things are. Somebody else does, and so I’m stuck with soothing frazzled nerves. It comes with the territory. Let me know how the rest of the concert went, will you?”

The naval officer nodded sympathetically. “Sure, George.”

Both men watched as their companion turned and walked rapidly toward the nearest stairway.

“What do you suppose that was all about?” the general wondered aloud.

His colleague shrugged. “Like he said, it’s probably the usual much ado about nothing.”

“Yeah.” The general was silent a moment, then added, “I wouldn’t have his job for all the diamonds in South Africa.”

The corridor was spotlessly clean and well lit by numerous overhead fluorescents. Doors were identified only by numbers. There were no windows. Fox and his assistant walked briskly, ignoring the occasional passing pedestrian.

“Sounds like Russian space-garbage to me, Brayton. If it was an accidental launching we’d have heard from them pronto, and if it was deliberate we’d know by now. Our sources aren’t that bad. So it’s got to be their junk.”

“The Molink people say no.” Brayton was thoughtful, precise, and not particularly imaginative. Fox found him very useful.

“What does the Kremlin say about it?”

“Naz drovya and how’s the weather out your way? They don’t know from nothin’.”

Fox grunted. “If it is theirs they might have plenty of reasons for not wanting to claim it. If the Molink people still say it ain’t and if it’s still behaving as erratically as it was when we first picked it up, it could still qualify as some new kind of surveillance job. Or it might be

another worn-out military satellite with its reactor intact, like the one that came apart over Canada a few years back. If either case is true, our Soviet friends will declare their innocence until we can slap some hard evidence in their faces.”

They reached the end of the corridor and pushed through the door at the far end. Beyond lay an auditorium alive with teletypes, oversized video screens, monitoring consoles and mildly frantic attendant personnel. Brayton and Fox headed straight for a center console around which several NSA people were clustered. One of the group noticed their approach and informed the others of the director’s presence.

“What’ve we got?” Fox asked curtly.

“Bunch of F-16s from McCord picked it up over the mountains, sir,” the man informed him. “It didn’t respond to multiple hailings. They tried calling it on all the standard frequencies. No response. Went right over the Trident sub base at Bremerton and at that point the local brass went through the roof. A couple of the fighters made a pass at it without getting a look-see—it was going too fast—but they claim they got a hit.”

“They would. Independent confirmation?”

“No apparent damage, so nobody knows yet if the pilots were lucky or just guessing, but whatever the reason, we’ve got another change of course.”

Fox’s eyebrows rose. Next to him Brayton mumbled, “Space-garbage doesn’t change course once it hits lower atmosphere.” His boss ignored him.

The operative turned back to the console, studied the constantly changing readouts. “Got a new estimated point of impact.” He looked up, gestured toward a map of the United States outlined in glowing colors on the big screen that dominated one wall of the auditorium. “Northern Wisconsin someplace.”