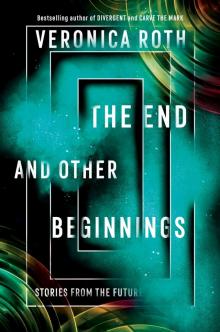

The End and Other Beginnings

Veronica Roth

Dedication

To the soft-hearted

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Inertia

The Spinners

Hearken

Vim and Vigor

Armored Ones

The Transformationist

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Books by Veronica Roth

Back Ad

Copyright

About the Publisher

“There must have been some kind of mistake,” I said.

My clock—one of the old digitals with the red block numbers—read 2:07 a.m. It was so dark outside I couldn’t see the front walk.

“What do you mean?” Mom said absently, as she pulled clothes from my closet. A pair of jeans, T-shirt, sweatshirt, socks, shoes. It was summer, and I had woken to sweat pooling on my stomach, so there was no reason for the sweatshirt, but I didn’t mention it to her. I felt like a fish in a tank, blinking slowly at the outsiders peering in.

“A mistake,” I said, again in that measured way. Normally I would have felt weird being around Mom in my underwear, but that was what I had been wearing when I fell asleep on top of my summer school homework earlier that night, and Mom seeing the belly button piercing I had given myself the year before was the least of my worries. “Matt hasn’t talked to me in months. There’s no way he asked for me. He must have been delirious.”

The paramedic had recorded the aftermath of the car accident from a camera in her vest. In it, Matthew Hernandez—my former best friend—had, apparently, requested my presence at the last visitation, a rite that had become common practice in cases like these, when hospital analytics suggested a life would end regardless of surgical intervention. They calculated the odds, stabilized the patient as best they could, and summoned the last visitors, one at a time, to connect to the consciousness of the just barely living.

“He didn’t just make the request at the accident, Claire, you know that.” Mom was trying to sound gentle, I could tell, but everything was coming out clipped. She handed me the T-shirt, skimming the ring through my belly button with her eyes but saying nothing. I pulled the T-shirt over my head, then grabbed the jeans. “Matt is eighteen now.”

At eighteen, everyone who wanted to participate in the last visitation program—which was everyone, these days—had to make a will listing their last visitors. I wouldn’t do it myself until next spring. Matt was one of the oldest in our class.

“I don’t . . .” I put my head in a hand. “I can’t . . .”

“You can say no if you want.” Mom’s hand rested gently on my shoulder.

“No.” I ground my head into the heel of my hand. “If it was one of his last wishes . . .”

I stopped talking before I choked.

I didn’t want to share a consciousness with Matt. I didn’t even want to be in the same room as him. We’d been friends once—the closest kind—but things had changed. And now he wasn’t giving me any choice. What was I supposed to do, refuse to honor his will?

“The doctor said to hurry. They do the visitation while they prepare him for surgery, so they only have an hour to give to you and his mother.” Mom was crouched in front of me, tying my shoes, the way she had when I was a little kid. She was wearing her silk bathrobe with the flowers stitched into it. It was worn near the elbows and fraying at the cuffs. I had seen that bathrobe every day since Dad gave it to her for Christmas when I was seven.

“Yeah.” I understood. Every second was precious, like every drop of water in a drought.

“Are you sure you don’t want me to take you?” she said. I was staring at the pink flower near her shoulder; lost, for a second, in the familiar pattern.

“Yeah,” I said again. “I’m sure.”

I sat on the crinkly paper, tearing it as I shifted back to get more comfortable. This table was not like the others I had sat on, for blood tests and pelvic exams and reflex tests; it was softer, more comfortable. Designed for what I was about to do.

On the way here I had passed nurses in teal scrubs, carrying clipboards. I passed worried families, their hands clutched in front of them, sweaters balled up over their fists to cover themselves. We became protective at the first sign of grief, hunching in, shielding our most vulnerable parts.

I was not one of them. I was not worried or afraid; I was empty. I had glided here like a ghost in a movie, floating.

Dr. Linda Albertson came in with a thermometer and blood pressure monitor in hand, to check my vitals. She gave me a reassuring smile. I wondered if she practiced it in a mirror, her softest eyes and her gentlest grins, so she wouldn’t make her patients’ grief any worse. Such a careful operation it must have been.

“One hundred fifteen over fifty,” she said, after reading my blood pressure. They always said that like you were supposed to know what the numbers meant. And then, like she was reading my mind, she added, “It’s a little low. But fine. Have you eaten today?”

I rubbed my eyes with my free hand. “I don’t know. I don’t—it’s the middle of the night.”

“Right.” Her nails were painted sky blue. She was so proper in her starched white coat, her hair pulled back into a bun, but I couldn’t figure out those nails. Every time she moved her hands, they caught my attention. “Well, I’m sure you’ll be fine. This is not a particularly taxing procedure.” I must have given her a look, because she added, “Physically, I mean.”

“So where is he?” I said.

“He’s in the next room,” Dr. Albertson said. “He’s ready for the procedure.”

I stared at the wall like I would develop X-ray vision through sheer determination alone. I tried to imagine what Matt looked like, stretched out on a hospital bed with a pale green blanket over his legs. Was he bruised beyond recognition? Or were his injuries the worse kind, the ones that hid under the surface of the skin, giving false hope?

She hooked me up to the monitors like it was a dance, sky-blue fingernails swooping, tapping, pressing. Electrodes touched to my head like a crown, an IV needle gliding into my arm. She was my lady-in-waiting, adorning me for a ball.

“How much do you know about the technology?” Dr. Albertson said. “Some of our older patients need the full orientation, but most of the time our younger ones don’t.”

“I know we’ll be able to revisit memories we both shared, places we both went to, but nowhere else.” My toes brushed the cold tile. “And that it’ll happen faster than real life.”

“That’s correct. Your brain will generate half the image, and his will generate the other. The gaps will be filled by the program, which determines—by the electrical feedback in your brain—what best completes the space,” she said. “You may have to explain to Matthew what’s happening, because you’re going before his mother, and the first few minutes can be disorienting. Do you think you can do that?”

“Yeah,” I said. “I mean, I won’t really have a choice, will I?”

“I guess not, no.” Pressed lips. “Lean back, please.”

I lay down, shivering in my hospital gown, and the crinkly paper shivered along with me. I closed my eyes. It was only a half hour. A half hour to give to someone who had once been my best friend.

“Count backward from ten,” she said.

Like counting steps in a waltz. I did it in German. I didn’t know why.

It wasn’t like sleeping—that sinking, heavy feeling. It was like the world disappearing in pieces around me—first sight, then sound, then the touch of the paper and the plush hospital table. I tasted something bitter, like alcohol, and then the world came back again, but not in the right way.

Instead of the ex

am room, I was standing in a crowd, warm bodies all around me, the pulsing of breaths, eyes guided up to a stage, everyone waiting as the roadies set up for the band. I turned to Matt and grinned, bouncing on my toes to show him how excited I was.

But that was just the memory. I felt that it was wrong before I understood why, sinking back to my heels. My stomach squeezed as I remembered that this was the last visitation, that I had chosen this memory because it was the first time I felt like we were really friends. That the real, present-day Matthew was actually standing in those beat-up sneakers, black hair hanging over his forehead.

His eyes met mine, bewildered and wide. All around us, the crowd was unchanged, and the roadies still screwed the drum set into place and twisted the knobs on the amplifiers.

“Matt,” I said, creaky like an old door. “Are you there?”

“Claire,” he said.

“Matt, this is a visitation,” I said. I couldn’t bear to say the word last to him. He would know what I meant without it. “We’re in our shared memories. Do you . . . understand?”

He looked around, at the girl to his left with the cigarette dangling from her lips, lipstick marking it in places, and the skinny boy in front of him with the too-tight plaid shirt and the patchy facial hair.

“The accident,” he said, all dreamy voice and unfocused eyes. “The paramedic kind of reminded me of you.”

He reached past the boy to skim the front of the stage with his fingertips, drawing away dust. And he smiled. I didn’t usually think this way, but Matt had looked so good that day, his brown skin even darker from a summer in the sun and his smile, by contrast, so bright.

“Are you . . . okay?” I said. For someone who had just found out that he was about to die, he seemed pretty calm.

“I guess,” he said. “I’m sure it has more to do with the drug cocktail they have me on than some kind of ‘inner peace, surrendering to fate’ thing.”

He had a point. Dr. Albertson had to have perfected the unique combination of substances that made a dying person calm, capable of appreciating their last visitation, instead of panicking the whole time. But then again, Matt had never reacted to things quite the way I expected him to, so it wouldn’t have surprised me to learn that, in the face of death, he was as calm as still water.

He glanced at me. “This is our first Chase Wolcott concert. Right?”

“Yeah,” I said. “I know that because the girl next to you is going to give you a cigarette burn at some point.”

“Ah yes, she was a gem. Lapis lazuli. Maybe ruby.”

“You don’t have to pick the gem.”

“That’s what you always say.”

My smile fell away. Some habits of friendship were like muscle memory, rising up even when everything else had changed. I knew our jokes, our rhythms, the choreography of our friendship. But that didn’t take away what we were now. Any normal person would have been stumbling through their second apology by now, desperate to make things right before our time was over. Any normal person would have been crying, too, at the last sight of him.

Be normal, I told myself, willing the tears to come. Just now, just for him.

“Why am I here, Matt?” I said.

Dry eyed.

“You didn’t want to see me?” he said.

“It’s not that.” It wasn’t a lie. I both did and didn’t want to see him—wanted to, because this was one of the last times I would get to, and didn’t want to, because . . . well, because of what I had done to him. Because it hurt too much and I’d never been any good at feeling pain.

“I’m not so sure.” He tilted his head. “I want to tell you a story, that’s all. And you’ll bear with me, because you know this is all the time I get.”

“Matt . . .” But there was no point in arguing with him. He was right—this was probably all the time he would get.

“Come on. This isn’t where the story starts.” He reached for my hand, and the scene changed.

I knew Matt’s car by the smell: old crackers and a stale “new-car smell” air freshener, which was dangling from the rearview mirror. My feet crunched receipts and spilled potato chips in the foot well. Unlike new cars, powered by electricity, this one was an old hybrid, so it made a sound somewhere between a whistle and a hum.

The dashboard lit his face blue from beneath, making the whites of his eyes glow. He had driven the others home—all the people from the party who lived in this general area—and saved me for last, because I was closest. He and I had never really spoken before that night, when we had stumbled across each other in a game of strip poker. I had lost a sweater and two socks. He had been on the verge of losing his boxers when he declared that he was about to miss his curfew. How convenient.

Even inside the memory, I blushed, thinking of his bare skin at the poker table. He’d had the kind of body someone got right after a growth spurt, long and lanky and a little hunched, like he was uncomfortable with how tall he’d gotten.

I picked up one of the receipts from the foot well and pressed it flat against my knee.

“You know Chase Wolcott?” I said. The receipt was for their new album.

“Do I know them,” he said, glancing at me. “I bought it the day it came out.”

“Yeah, well, I preordered it three months in advance.”

“But did you buy it on CD?”

“No,” I admitted. “That’s retro hip of you. Should I bow before the One True Fan?”

He laughed. He had a nice laugh, half an octave higher than his deep speaking voice. There was an ease to it that made me comfortable, though I wasn’t usually comfortable sitting in cars alone with people I barely knew.

“I will take homage in curtsies only,” he said.

He pressed a few buttons on the dashboard and the album came on. The first track, “Traditional Panic,” was faster than the rest, a strange blend of handbells and electric guitar. The singer was a woman, a true contralto who sometimes sounded like a man. I had dressed up as her for the last two Halloweens, and no one had ever guessed my costume right.

“What do you think of it? The album, I mean.”

“Not my favorite. It’s so much more upbeat than their other stuff, it’s a little . . . I don’t know, like they went too mainstream with it, or something.”

“I read this article about the lead guitarist, the one who writes the songs—apparently he’s been struggling with depression all his life, and when he wrote this album he was coming out of a really low period. Now he’s like . . . really into his wife, and expecting a kid. So now when I listen to it, all I can hear is that he feels better, you know?”

“I’ve always had trouble connecting to the happy stuff.” I drummed my fingers on the dashboard. I was wearing all my rings—one made of rubber bands, one an old mood ring, one made of resin with an ant preserved inside it, and one with spikes across the top. “It just doesn’t make me feel as much.”

He quirked his eyebrows. “Sadness and anger aren’t the only feelings that count as feelings.”

“That’s not what you said,” I said, pulling us out of the memory and back into the visitation. “You just went quiet for a while until you got to my driveway, and then you asked me if I wanted to go to a show with you.”

“I just thought you might want to know what I was thinking at that particular moment.” He shrugged, his hands resting on the wheel.

“I still don’t agree with you about that album.”

“Well, how long has it been since you even listened to it?”

I didn’t answer at first. I had stopped listening to music altogether a couple months ago, when it started to pierce me right in the chest like a needle. Talk radio, though, I kept going all day, letting the soothing voices yammer in my ears even when I wasn’t listening to what they were saying.

“A while,” I said.

“Listen to it now, then.”

I did, staring out the window at our neighborhood. I lived on the good side and he lived on the bad side, go

ing by the usual definitions. But Matthew’s house—small as it was—was always warm, packed full of kitschy objects from his parents’ pasts. They had all the clay pots he had made in a childhood pottery class lined up on one of the windowsills, even though they were glazed in garish colors and deeply, deeply lopsided. On the wall above them were his mom’s needlepoints, stitched with rhymes about home and blessings and family.

My house—coming up on our right—was stately, spotlights illuminating its white sides, pillars out front like someone was trying to create a miniature Monticello. I remembered, somewhere buried inside the memory, that feeling of dread I had felt as we pulled in the driveway. I hadn’t wanted to go in. I didn’t want to go in now.

For a while I sat and listened to the second track—“Inertia”—which was one of the only love songs on the album, about inertia carrying the guitarist toward his wife. The first time I’d heard it, I’d thought about how unromantic a sentiment that was—like he had only found her and married her because some outside force hurled him at her and he couldn’t stop it. But now I heard in it this sense of propulsion toward a particular goal, like everything in life had buoyed him there. Like even his mistakes, even his darkness, had been taking him toward her.

I blinked tears from my eyes, despite myself.

“What are you trying to do, Matt?” I said.

He lifted a shoulder. “I just want to relive the good times with my best friend.”

“Fine,” I said. “Then take us to your favorite time.”

“You first.”

“Fine,” I said again. “This is your party, after all.”

“And I’ll cry if I want to,” he crooned, as the car and its cracker smell disappeared.

I had known his name, the way you sometimes knew people’s names when they went to school with you, even if you hadn’t spoken to them. We had had a class or two together, but never sat next to each other, never had a conversation.

In the space between our memories, I thought of my first sight of him, in the hallway at school, bag slung over one shoulder, hair tickling the corner of his eye. His hair was floppy then, and curling around the ears. His eyes were hazel, stark against his brown skin—they came from his mother, who was German, not his father, who was Mexican—and he had pimples in the middle of each cheek. Now they were acne scars, only visible in bright light, little reminders of when we were greasy and fourteen.