The Music of Us (Still Life with Memories Book 3)

Uvi Poznansky

The Music of Us

Still Life with Memories

Volume III

A Novel

Uvi Poznansky

The Music of Us©2015 Uvi Poznansky

All rights Reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

This novel can be read as a standalone novel, as well as a part of Still Life with Memories, a series describing events in the life of a unique family from multiple points of view.

Published by Uviart

P.O. Box 3233 Santa Monica CA 90408

Blog: uviart.blogspot.com

Website: uviart.com

Email: [email protected]

First Edition 2015

Printed in the United States of America

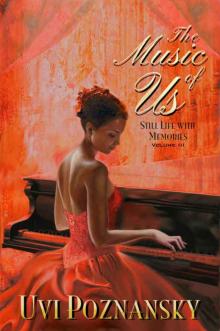

Book design, cover image and cover design

Uvi Poznansky

Contents

I Am Music

I’ll be Dreaming You

With a Light from Above

Silence of the Muse

The Letter

Those Green Eyes

A Lowdown Groove

Memory is a Liar

Bei Mir Bistu Shein

The Fifth

Always Remember

Amazing Grace

To Find Myself Forsaken

Repose

Until You’re in My Arms

War Can Wait

Make it One for the Heartbreak

When It’s Her You Embrace

The Winter Wind that Wrapped Us in a Chill

I Pine for You, Day and Night

Yours Forever I’m Going to Be

I Will Help You Rise

About this Book

About the Author

About the Cover

A Note to the Reader

Bonus Excerpts

Excerpt: A Peek at Bathsheba

Excerpt: The Edge of Revolt

Excerpt: Apart From Love

Books by Uviart

My Own Voice

The White Piano

The Music of Us

Apart from Love

The David Chronicles

Rise to Power

A Peek at Bathsheba

The Edge of Revolt

A Favorite Son

Twisted

Home

Children’s Books by Uviart

Jess and Wiggle

Now I Am Paper

I Am Music

Chapter 1

Normally I recognize life-changing events only in retrospect. Not so tonight. Given what’s just happened I know right away that this moment is critical. It would separate us, and the divide will grow, it will continue to widen beyond any hope of finding a way to bridge it.

I find it difficult to put it in words, to explain, even to myself, the significance of that phone conversation, of that one sentence, the one phrase I’ve hoped never to hear.

And I ask myself, Is this truly a surprise? Perhaps that word has been there for years, hissing persistently in my ear, waiting for me to accept it. All the while I pretended there was silence, nothing but silence until now, until this ring.

By nature I take my time realizing things. When I met Natasha, it took me a while to grasp the full meaning of being next to her, so close to her genius. I found the best part of who I was as I listened to the way she used to play the piano, the way she used to compose. Then, when our son was born, I didn’t quite understand my role as a father, and even today I’m still learning.

He hates me now, hates me to the point of dropping out of high school simply to spite me. At the station this morning Ben looked anxiously at the bus as it arrived out of the mist. Meanwhile I remained sitting on the wet bench, hanging my head between my shoulders, looking at my fingernails. They looked blurry.

“Goodbye,” he blurted, leaping to his feet. “I’m outa here.”

Both of us knew he was headed nowhere and had no plans for his future, beyond a one-way flight ticket to Italy which he couldn’t even afford. How he got it was a mystery to me.

“Don’t go,” I said, one more time.

To which he said, “I can’t stay.”

I tried to blink away the film of tears, which is where I saw the image of my own father, years ago. In a flash I remembered: he had been shrinking into the distance between this and that murky spot on the train window, left behind as I headed for a military induction center. I had thought I would come back one day with a measure of success that was not based on his advice. I had thought we would have time to mend the connection between us. Except for an exchange of letters, I saw him only one time after that. He had passed away a year later, which now brought to me the notion of my own mortality.

“Write to me, stay in touch,” I told my son. “And take care of yourself.”

I didn’t think he heard me, but as the bus lurched, steering into the middle lane, Ben yelled something over the noise. I think he said, “Take care of Mom.”

Watching the back tires splashing across a puddle as they turned the corner, I murmured, “I don’t quite know how, son.”

Back home I found Natasha sitting at her instrument with a vacant look on her face. In the background, the radio was making static noise, while capturing two stations at once with equal disregard to clarity. On one of them was a speech by President Nixon, calling the silent majority to join him and show solidarity with the Vietnam war effort, followed by some incoherent discussion among analysts trying to figure out what kind of majority it was and why, given its size, it remained silent until now.

On the other station was the song,

What day it was I can’t recall

Time was so slow, down to a crawl

All I could do was reach for you

Or drown in dreams, so sad, so blue

My arms open, just for you

I tried adjusting the dial, tried repositioning its antennae, and annoyed at myself for failing to get a clear sound of either one of the stations, I turned the radio off.

I considered asking Natasha to play something for me, but didn’t. Instead I bent over the top of the piano, where the bust of Beethoven was perching, and touched my cheek to the cold reflection.

This time Natasha lifted her face to me. I plopped next to her on the bench and reached for her hand. Expecting no answer I said, “This place seems so empty, all of a sudden.”

To my surprise she looked around and said, “So it does.”

“He’s gone.”

“Who?”

“Ben.”

“Oh,” she said.

“I put him on the bus and waved goodbye to him.”

At that, she fell silent. A moment later she whispered, “Don’t I know how it feels.”

“You do? Really?” I asked. “What is it, exactly, that you feel?”

She shrugged.

“Tell me, Natasha.”

“You wouldn’t understand it.”

“Try me.”

The phone started ringing just as she was about to tell me something. When I got up to answer, she waved her hand, which I understood, somehow, even without words.

Oh, never mind.

And as I lifted the receiver from its cradle I heard her mumbling something behind me, back in the living room. I held my breath, trying to catch the sound of her voice.

“Can’t you tell?” she said, to no one in particular. “I feel loss.”

For a moment I thought she was talking about our son, leaving us, or else about me, having an

affair. Perhaps it made her stop calling me Lenny, which irked me. That, I thought, was why she treated me as a stranger.

“Is he blind?” She shook her head in disbelief. “Can’t this man read my face? I feel as if I put my brain on a bus and waved goodbye to it.”

Her doctor was on the other end of the line. He told me to schedule an appointment as soon as I can for an X-Ray for my wife.

“Hasn’t she been through enough?” I asked, reluctantly. “So many exams, so many prescriptions, none of which has helped her so far. From one week to another I see her condition worsen.”

“This time,” he said, over my complaints, “it’s a head X-ray.”

“What for?”

“Just to rule out one particular thing.”

“What kind of a thing?”

He hesitated, perhaps wanting to spare me some complicated medical term and the worries that come along with it.

So I persisted. “Tell me,” I said. “What is it you wish to rule out?”

And he said, “Alzheimer’s.”

❋

He cannot be right, can he? My wife is forty-five, much too young for anyone to connect her name with an affliction affecting the old. So I think about what he said for a few days, during which I do not schedule any appointments for her. Instead I just stay around her and try to focus on my writing, which is not easy because, just because. She is agitated at times, other times she is looking for her diary, and even if I place it right there in front of her, she cannot bring herself to write a single sentence, and even if she could, it’s hard to decide which has become worse: her handwriting or her spelling.

“What is it, dear?” I ask. “Tell me.”

“I just sat down at my piano and tried to buckle my seat belt.”

“You must be tired, really tired,” I say. “Go to bed.”

In my heart I curse myself for being stuck in a rut, and curse her for pulling me down there in the first place. So to exact a little revenge on her: I take the diary, after she has gone to the bedroom, and for the first time, without regard to her privacy, I open it.

I open it to the last legible page. It is dated exactly a year ago, and in it Natasha says:

Once I find my way back, my confusion will dissipate, somehow. I will sit down in front of my instrument, raise my hand, and let it hover, touching-not-touching the black and white keys. In turn they will start their dance, rising and sinking under my fingers. Music will come back, as it always does, flowing through my flesh, making my skin tingle. It will reverberate not only through my body but also through the air, glancing off every surface, making walls vanish, allowing my mind to soar.

Then I will stop asking myself, “Where am I,” because the answer will present itself at once. This is home. This, my bench. The dent in its leather cushion has my shape. Here I am, at times turbulent, at times serene. I am ready to play. I am music.

But until then I am frightened, frightened to the point of panic. Even in my daze I sense the eyes of strangers. Their glances follow me down the street. Stumbling aimlessly from one place to another in the darkening city, turning around this street corner and that, I am amazed to realize that every building looks like an exact replica of the previous one. It baffles me, but I tell myself, with an increasingly shaky tone, that I am not lost. I cannot allow myself to think that I am. I will find my way, right after taking a deep breath to regain my calm. Then I will try to separate familiar lines out of this urban chaos.

Perhaps this intersection is not that far away from home. I am trying to map it in my mind, but the street signs are of no help, of course. Reading them has become such a chore lately, forcing me to traverse one garbled letter after another and connect them without forgetting the beginning of the word. I would like to believe that if street signs were written in notes I could play them in my mind. I could make some sense of them, because that is the language I understand. I am music.

The streetlamp next to the curb seems familiar, I think. So does the way electric light flickers inside, buzzing on and off, off and on. It strobes with a certain rhythm, as if trying to convey some coded message. I have heard this sequence before. It has a particular type of silence towards the end of it, which I sense quite vividly, but cannot explain in words.

The fear of finding myself lost is not a new feeling. It has been with me as long as I can remember, erupting now and again ever since I was a six-year-old girl. I never tell anyone about it, not even my husband, Lenny. Why? Because he seems to adore me not for my lips, which have lost their rosy shine in recent years, and not for my red hair, which has started to thin out, but for the magic I evoke, for the way I used to play, reciting complex, truly challenging pieces with barely a glance at the notes. He finds it inspiring.

My son, Benjamin, is in school. He knows the name of the street where we live and would be surprised to learn that every once in a while I forget it. I tend to forget the name of the city, too, so I ask him, and repeat what he says. It stays with me a while longer this way.

I never tell him about myself at his age, because it may open his eyes to see me, see who I am becoming. To him I must remain a mother. To my husband I must remain a woman. I keep the truth from both of them. No one in my family should guess that having lost my way, I am becoming a child.

This is the memory I withhold from them: at the end of my first day in school, I stood outside by the gate. I waited. I waited there a long time. No one came to pick me up. So I told myself that perhaps I could find the way by myself. I stepped out onto the street. It looked unfamiliar. By high noon, gone were the long tree shadows that used to point the direction back home. Hours later, after a frantic search, my father found me at the other end of town, wandering aimlessly along the Santa Monica beach.

Perhaps he expected to see an odd, bewildered look on my face. But no, I fixed my eyes at the sea melding into the sky. The only way to tell them apart was to note that it was creased, as if someone pulled a cloth across it. I took my shoes off, felt the wet sand, and listened to the yawn of the waves. I was happy.

So now, what can I do but what I did back then: try to trace my way back to where I started? As an adult I should be able to do it.

After all I have prepared myself. I have learned to pay attention to details. I study them up close, perhaps to the exclusion of seeing what is around them. I admire the beauty of things, the way they present themselves to your imagination when you really focus. I note how a chip of paint flakes off a door and swirls in a gale of wind or how the handle of the door reflects my image in reverse, distorting it over its curvature as I step side to side and back again. No one else would bother over such trifles, but I marvel at them.

Reading what Natasha wrote I suddenly recall the date, the exact date she must have done it, because that was the first time she got lost on her way to the grocery store, and a cop found her five miles down the road in the opposite direction and brought her back home. He told me that she could not tell him her address, and boy is she lucky for his patience, and so am I, we should both fall to our knees and give thanks to God, because it was a major headache for him, I mean for the cop not for God, to figure out where she lived by the few clues she managed, somehow, to offer.

And even as this brings back such a sad milestone in our lives I find myself amazed, as I read on, that Natasha could capture the dialogue with him with such clarity:

“D’you know where you’re going, Miss?” a policeman asks me.

“No, not exactly,” say I. “I think I’m lost.”

“You know your address?”

“All I recall is how the gate looks, out in front.”

He gives me a look.

“All right,” he says at last. “Describe it.”

“One of the slats along the fence has been knocked off its vertical position, and it is hung, somehow, by a rusty nail, dangling from the horizontal slat in the back,” I tell him, doing my best to come up with a complete description. “A crooked hinge is fastened to it, whi

ch lets the gate sway, turning back and forth with this sound, this harsh, repetitive sigh.”

He can’t help rolling his eyes.

“Very well,” he says, tersely. “That’s a lot of help.”

“It is?”

“Not exactly,” he mutters, under his breath. “Now, try to recall: when you peek over the fence, is there a number up there, on the building?”

“There is,” I say.

He cannot hide his relief. “Of course there is! So tell me, what is it?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Can you draw it for me, at least?”

I shake my head, No. “All I recall is that beyond the gate are the weeds, swishing left and right of the pathway.”

“Weeds,” he echoes, raising an eyebrow, which complicates things for him because it stops him from performing another repetition of what he has been doing so far, which is rolling his eyeballs.

“Yes,” say I, “And after that, a diagonal shadow.”

To which he throws his hands up in the air, “Diagonal shadow!” he mutters. “What did I expect! Naturally that’s what I get, asking for a number!”

This diary, I now realize, is a precious, unintended gift she left me. If I go back far enough through its entries I can put her together again. I can resurrect the woman lost to me. Her ghost may then become more real to me than the closeness of her body.

I turn the page, and hear her voice rising from its rustle even as she tosses fitfully in her sleep, down there in our bedroom.

I avoid telling the cop that as I recall, the shadow is climbing up, ever so stealthily, into the apartment building, suggesting a hint of the stairs. And I avoid telling him that when you lift your eyes to the window, up above on the first floor, you can see that the embroidered flowers have faded in the sun, especially near the bottom edge of the curtain, where the fabric is straightening out of its folds.

This is where we live. This is safety. It is the place I must find.