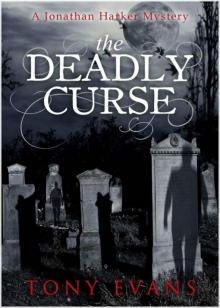

The Deadly Curse

Tony Evans

The Deadly Curse

A Jonathan Harker Mystery

Tony Evans

© Tony Evans 2014

Tony Evans has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published in 2014 by Endeavour Press Ltd.

Table of Contents

Prequel: Valley of the Kings, Ancient Egypt, 1,326 BC

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Extract from Devil May Care by Tony Evans

Prequel: Valley of the Kings, Ancient Egypt, 1,326 BC

Grand Vizier Actaroth had served his master, Pharaoh Karnos II, for over two decades and was about to conduct his last solemn duty: overseeing the burial of the god-king and his consort Queen Merhote. Actaroth stood some distance from the entrance to the long tunnel that had been dug deep into the hillside, and which led to the tomb chamber that had been prepared many years earlier. The great age of pyramid building had long passed, and the arid valley alongside the west bank of the Nile was now the chosen resting place for Egypt’s rulers.

The tomb had already been furnished with its valuable grave goods and holy scrolls, and all that remained to be added were the two sarcophagi that contained the mummified bodies of the pharaoh and his queen. As Actaroth looked towards the entrance of the deep valley, he could see the gathering cloud of red dust signalling the approach of the funeral party. Two wooden sledges pulled by a team of oxen each carried a stone sarcophagus, surrounded by a large group of mourners: these included the pharaoh’s favourite concubines and courtiers, and two priestesses representing Nephthys and Isis, the goddesses of death and rebirth.

There was one notable omission from the funeral procession, Actaroth thought. The High Priest of Egypt, Nebet, should have been present, but he had unaccountably vanished on the day that Karnos breathed his last. Actaroth had heard rumours that the new pharaoh was jealous of the priest and had sent Nebet to a secret grave. Others believed that Nebet had feared for his life when Karnos died and had gone into hiding.

The procession halted outside the entrance to the tomb, whilst the two sarcophagi were taken one at a time into the bowels of the mountain, hauled by a team of slaves and followed by a select group of mourners carrying oil lamps. After more than an hour the party re-emerged blinking into the harsh sunlight.

Months earlier, a huge stone had been dragged up a man-made slope of packed sand so that it stood poised above the entrance of the tomb. It had taken six weeks to position it in exactly the right place. Great baulks of timber – a precious commodity in Ancient Egypt – had been wedged under the stone and the sand dug away from around it. Now the final act of interment was to take place. The Grand Vizier approached the entrance and gave the order. Slaves heaved at the coils of rope which had been looped around the base of the timbers and the massive stone slab, now unsupported, dropped into place with a ground-shaking thud, sealing the tomb of Karnos and his queen for all eternity. The next day, a party of slaves and workmen would return and conceal the huge stone with a mound of rock and rubble.

As the procession and the two empty sledges left the Valley of the Kings behind them, Actaroth turned round to take one final look at the pharaoh’s last resting place. A pair of squawking vultures, perhaps propelled by some instinctive empathy with death, were circling impotently around the barrier which concealed the entrance to the tomb. An enigmatic smile played briefly upon the Vizier’s lips, impossible to interpret, but suggestive of a man in possession of a great secret.

Chapter 1

It was mid-afternoon when my wife and I arrived at Paddington after a swift and pleasant journey from Exeter. We had not seen our good friend Abraham Van Helsing for over a year, and it was with great anticipation that we left the railway station en route to his recently built villa in St John’s Wood.

As the four-wheeler negotiated the busy thoroughfare of the Edgware Road, Mina leaned forward to obtain a better view from the carriage window.

‘We must come to London more often,’ she said. ‘These noble buildings and bustling crowds put Exeter to shame. They make me feel quite provincial.’

‘The metropolis in small doses is all very well,’ I replied. ‘Certainly the next few days should prove interesting. A visit to Professor Van Helsing is rarely dull. Do you intend to reveal the reason behind your curiosity regarding his stay in Mesopotamia?’

Mina smiled. The Professor had recently returned from a three-month expedition to Baghdad, where he had been studying ancient manuscripts of the Babylonian astronomers. It was, however, his experiences of life in the modern Near East that my wife wished to encapsulate. Her latest novel, The Bessemer Inheritance, was about to appear in the new year – Mina was now well established as a lady novelist of the more sensational variety – and she had already decided that her next publication would have as its setting a more exotic location than the salons of Bloomsbury or Knightsbridge.

‘I would not be so foolish as to try to conceal anything from our friend,’ she said. ‘Besides, I’m sure that once he becomes aware of my projected story he will think of all kinds of details with which I can beguile my readers. Are there still sultans and harems in Baghdad, I wonder?’

‘If not, I see no reason why you should not invent them,’ I said. ‘After all you are writing a work of fiction, which will bear little relation to the mundane life led by such as you or me. But I see we are close to Van Helsing’s villa. I must give our driver a generous gratuity to compensate for the brevity of our journey.’

*

We were pleased to find Professor Van Helsing in excellent spirits – perhaps with a few more strands of grey in his beard than I had remembered, but heavily tanned and as vigorous as ever. After we had exchanged greetings and he had ordered tea, he turned to Mina.

‘Let me see, my dear – your son must be a year old now? And still in good health, I trust?’

‘Correct on both counts! He’s being looked after – and I daresay spoilt terribly – by his doting aunt whilst we are away from home. His first birthday was last Saturday. It’s very strange: we had already decided to call him Quincey if he was a boy, in memory of dear Quincey Morris, and then he was born on the anniversary of his namesake’s death. Now he will have both a birth date and a Christian name to keep our old colleague’s memory alive.’

At the mention of Quincey Morris’s name Van Helsing’s happy countenance momentarily clouded. I understood and shared his sadness. Four years ago, on 6th November 1893, our brave companion had been killed during our final confrontation with Count Dracula – but he had lived long enough to see the evil creature crumble into dust and the curse with which he had afflicted Mina vanish forever.

Van Helsing leaned forward and took my wife’s hands in his. ‘He will not be forgotten, my dear. Young Quincey Harker will see to that. Now, there is still an hour or two before dusk. If you have recovered from your journey, let us walk the short distance to Regent’s Park. If you and Jonathan have not changed your character, I feel sure that you will have included stout walking shoes amongst your luggage. I will take the opportunity to tell you about the guest who will be joining us for dinner this evening. There is a legal matter upon which she requires advice and I believe that it is singularly suited to Jonathan’s talents.’

I threw up my hands in jocular imitation of dismay. ‘Do you mean that it involves some occult experience? I had hoped that our visit to London might be free of such adventures.’

Our friend smiled mysteriously, leading me to feel that my jest might well have struck

upon the truth.

*

As Mina and I dressed for dinner later that evening, I reflected upon what the Professor had told us about his guest. He had described Miss Sarah Wilton as a serious minded young woman in her late twenties, who had the distinction of being amongst the first of her sex to graduate from University College, London. She was now employed there as an assistant lecturer in Ancient Languages and Egyptology, and it was at that progressive institution that she and Van Helsing had met. Van Helsing would not elaborate on the legal question that she wished to discuss, politely suggesting that her query would be best raised in person.

Mina adjusted her coiffure in front of the large cheval mirror, which stood in one corner of our bedroom. ‘Really, Jonathan, I had hoped that you would be able to escape the law for a few days at least,’ she said. ‘You already take on far too much, in my opinion. When is Mr Joplin intending to make you a senior partner? I’m sure the practice could not survive without you.’

My status as a junior partner at the Exeter firm of Joplin, Kaplan and Penfold, Solicitors at Law, was a matter of contention between Mina and I, and so I adopted the effective – I hoped – marital strategy of changing the subject.

‘Miss Wilton is evidently too modern to feel the need for a chaperone,’ I said. ‘I wonder if this is the first time she has dined with the Professor?’

Mina paused in her attentions to an unruly strand of hair. ‘Van Helsing has been widowed for more than ten years,’ she said. ‘He certainly has all the attributes of an eligible man, except perhaps for his excessive intelligence. No woman’s secrets would be safe from him. But I suspect that Miss Wilton is as confirmed a “bachelor” as he.’

*

In the event, Sarah Wilton was not quite what either of us had anticipated. I had expected a somewhat severe and humourless young woman of the bluestocking variety, but instead she had a pleasant charm allied to her undoubted intellect. After the usual introductions and once we had taken our places in Van Helsing’s comfortable dining room, she turned to my wife with a smile.

‘I understand that you are a successful novelist,’ she said. ‘You must be very proud of your achievements.’

Mina blushed. ‘They hardly rank with yours, Miss Wilton. As a female graduate and a university lecturer, you are a far rarer specimen than I. After all, novel writing is one of those occupations traditionally undertaken by our sex. And if you have read my work, you will be aware that it does not set out to rival Dickens or the Brontë sisters – or even the late Mrs Oliphant.’

Sarah shook her head. ‘Don’t belittle yourself. I greatly enjoyed The Secret of Lady Connaught and it left me in a far better frame of mind than Jane Eyre. As for Dickens, I have always considered reading his work to be a rare penance, best reserved as a punishment for undeserving school children. But should we be discussing English literature at dinner? I’m sure that Mr Harker and Professor Van Helsing would prefer that we touched on the fashions of the day and the latest peccadilloes of high society.’

As our fellow guest spoke it occurred to me that her vein of facetious humour had much in common with that of my wife – unlike her physical appearance, which was very different. In contrast to Mina’s tall, slim figure, pale blond hair and light complexion, Sarah’s dark eyes, strong frame, olive skin and black curls suggested a Mediterranean ancestry.

‘Believe me, Miss Wilton, serious conversation holds no perils for me,’ I said. ‘I have learned to submit to it on a daily basis. But I understand from Abraham – Professor Van Helsing – that there is a legal matter on which you seek my advice?’

Before Sarah could reply, Maxwell, Van Helsing’s butler, arrived carrying a steaming tureen.Van Helsing stood up and with typical informality helped his servant lower the receptacle onto the table. ‘Let me make a suggestion. Mrs Crowther’s mulligatawny soup is best eaten whilst it is hot. I propose that we postpone discussing Miss Wilton’s problem until we have finished our dinner and have adjourned to the drawing room. Meanwhile, I will exercise the privilege of a host and entertain you with some anecdotes of my recent visit to Mesopotamia. I dare say you will enjoy hearing some of the more lurid details of life in the bazaars and casbahs of Baghdad. I promise to avoid any topics that might serve to lessen our appetite, as I believe that there is an excellent baked salmon in prospect. Maxwell, you may leave us – I’m sure my guests are happy to serve themselves. Jonathan, do pour us some wine.’

*

As Van Helsing had intimated, the dinner that his cook had prepared for us was first-rate, and we left the table in great good humour. The Professor’s drawing room was not large, but it was comfortably furnished and a bright coal fire flamed in the fireplace. Even accounting for the fire, the room seemed particularly warm for early November. Then I noticed the large, ornate cast iron radiators that stood against opposite walls of the room. Van Helsing followed my gaze.

‘An excellent invention,’ he said, ‘if somewhat expensive. I understand that Windsor Castle has recently been equipped with a similar system – on a rather grander scale. Will you take some port, Miss Wilton? And you, Mina?’

The ladies answering in the affirmative, the Professor filled their glasses and then our own. Sarah Wilton took an appreciative sip and turned to me with a smile.

‘Perhaps now I can trouble you with my question,’ she said. ‘Of course the Professor is already aware of the matter of which I speak, but I am sure he will not mind my repeating the essentials – and I trust that Mrs Harker will be happy to hear my story.’

When Mina and our host nodded in acquiescence, Sarah put down her glass and began her account.

‘My father was the late Sir Edward Wilton,’ she said. ‘My mother died when I was six years old. Father died three months ago, aged just fifty-one: he had been excavating in the Nile Delta and succumbed to typhoid fever, which is endemic to that area.’

‘His name sounds familiar,’ Mina said. ‘Was not Sir Edward the Egyptologist who discovered a pharaoh’s tomb – let me think – about ten years ago?’

‘You are correct,’ Sarah said. ‘In February 1886 my father led an expedition to the Valley of the Kings on the west bank of the Nile, near Thebes. Of course, most of the tombs there have been ransacked by grave robbers centuries ago.’

Van Helsing interjected. ‘Sir Edward pioneered a unique method for finding as yet undiscovered burial sites, I believe.’

Sarah nodded. ‘He did. When my father was a young man, he was rash enough to join a hot air balloon flight that took off near Dorchester, conducted by the French adventurer, Paul Séjour. Monsieur Séjour underestimated both the strength of the wind and height to which they would rise, with the result that the balloon travelled too far south and landed in Weymouth Bay. Fortunately, the sea was calm and a fishing boat was on hand to rescue them. However, at the start of their perilous flight the balloon had travelled over Maiden Castle – it’s really misnamed as it’s not a castle at all, but an ancient hill fort constructed of massive earth mounds and ditches. As they passed over the old earthworks, my father – who knew the area very well – noticed that a number of pathways, ancient trenches and other man-made features, which could clearly be seen from the balloon were invisible from the ground.

‘The significance of this insight did not escape him, but he was sufficiently cautious to keep his idea to himself until he could take full advantage of it. That opportunity did not arise until twenty years later, when he received a large and unexpected legacy. Now a wealthy man, my father was able to finance and lead a private exploration of the Valley of the Kings: the Wilton Expedition, as it became known. His ample funds allowed him to transport one of Henri Dupuy de Lôme’s new hydrogen balloons from France to Egypt, and he made several flights over the East Valley. He made detailed sketches of the terrain below and, as he suspected, discovered traces of ancient constructions never mapped before. Then Sir Edward and his colleagues examined each indicated site on foot. The last of these led to their discovery of the tomb of

Karnos II and of Queen Merhote, who was buried with him. The burial took place during the Eighteenth Dynasty, approximately 1,300 years BC.’

‘Forgive my interrupting,’ Mina said. ‘But was the death of the queen a happy – or, should I say, unhappy – coincidence? Unless, of course, they opened up the tomb a second time for her at some later date.’

Sarah smiled. ‘That would have been impracticable. No, Mrs Harker, I’m afraid your suspicions are correct. Although there was no absolute requirement for a pharaoh’s queen to join him in death, in practice, many opted to do so. We can be fairly sure that Merhote took poison in time to accompany her husband to the next world, where they would live together for eternity.’

‘Eternity! Let us hope the couple were more than usually compatible!’ Mina exclaimed. ‘But do continue, Miss Wilton.’

‘I’ll try to keep my narrative brief. Shortly after his discovery, Sir Edward brought the contents of the tomb back with him to England, including the two sarcophagi containing the inner coffins that held the mummified remains of Karnos and Merhote. At first they were stored in a secure warehouse managed by my father’s bank, Havelocks. Then, for three months, these fascinating treasures were put on public display in the British Museum, where they were seen by thousands of people. After that the most valuable items were taken by my father to his country house in Dorset, where they were kept secured in a strongroom until his death. Scholars were allowed to view them strictly by appointment, but they were no longer available for the public to see. There was some attempt to keep them in the museum, but my father was able to establish his legal ownership.’

As Sarah spoke I suddenly recollected reading an account of this peculiar arrangement in the Times. I was then in my first year at Oxford and remembered that most of my fellow students were in agreement with that newspaper, which felt that Sir Edward Wilton had no business keeping these priceless treasures to himself.