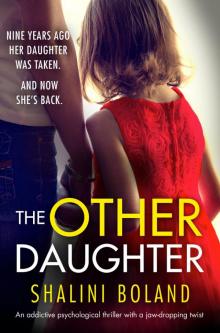

The Other Daughter: An addictive psychological thriller with a jaw-dropping twist

Shalini Boland

The Other Daughter

An addictive psychological thriller with a jaw-dropping twist

Shalini Boland

Books by Shalini Boland

The Secret Mother

The Child Next Door

The Silent Sister

The Millionaire’s Wife

The Perfect Family

The Best Friend

The Girl from the Sea

The Marriage Betrayal

Available in audio

The Secret Mother (Available in the UK and the US)

The Child Next Door (Available in the UK and the US)

The Silent Sister (Available in the UK and the US)

The Perfect Family (Available in the UK and the US)

The Marriage Betrayal (Available in the UK and the US)

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Epilogue

The Perfect Family

Hear more from Shalini

Books by Shalini Boland

A letter from Shalini

The Marriage Betrayal

The Secret Mother

The Child Next Door

The Millionaire’s Wife

The Best Friend

The Girl from the Sea

The Silent Sister

Acknowledgements

For my brave and beautiful daughter who I love more than life xxx

1

Then

She’s inside a nightmare. She’s inside hell. And nothing will ever be the same again.

The gears grind as Catriona puts her clunky old Ford Fiesta into second and turns right into slow-moving three-lane traffic. November rain lashes the windscreen and the wipers move frantically, barely making a difference, just sweeping with a dull squeak as water puddles down the glass. She can’t even remember getting into the car. She just knew she couldn’t stay in the house. Not afterwards.

A van honks to her left. She glances across to see an angry man mouthing something and making rude hand gestures. Catriona realises she’s drifted into the wrong lane, so she jerks the wheel in the opposite direction, overshooting and causing more horns to blare. ‘What does it matter anyway?’ she mutters to herself. ‘Who cares.’ Her nose is running so she wipes her forefinger across her top lip, glancing in the rear-view mirror as she does so. She realises that her hands are still caked in mud. So now she has both mud and snot smeared across her face. Normally this would concern her. Not today. Not now. Not ever again. Still, she wipes her face again, with the sleeve of her sweatshirt this time.

More vehicles flash and beep her. She’s trembling. She needs to get off the road. Up ahead are signposts into the shopping-centre car park. She’ll turn in there. Park for a moment. She doesn’t want to think about what she’ll do after that.

There’s a queue of traffic to get in, but eventually Catriona reaches the entrance of the multi-storey, drives in and pulls into a narrow parking space that faces a grey breeze-block wall. She kills the engine. The wipers come to a stop in the centre of the windscreen. It’s quieter in here, away from the drumming rain and the roar of traffic. A sob almost escapes her lips, but she can’t let it out. She doesn’t deserve the luxury of crying.

She stiffly exits the car, closing the door after her. She doesn’t bother locking it. She doesn’t know what she’s doing, where she’s going. She just follows the pedestrian signs to ‘Exit and Shops’ then pushes open the heavy swing doors that lead into the bright, white, clean shopping centre. A change in air pressure, the echoing sound of music around her.

Her body doesn’t feel as though it’s under her control, and she’s freezing all over despite the heat pumping through the mall. There’s a coffee kiosk up ahead with tables and chairs ranged around it, interspersed with tall palms and frond-like plants. It’s almost full – people coming and going, getting their caffeine fixes. But there are also a few women chatting leisurely and sipping their lattes. A water feature trickles and bubbles down one side of the café, and on the other side is a children’s play area. The sound of running water makes Catriona need the loo. She glances around for a bathroom, spots a sign and heads towards it.

Inside a cubicle, she relieves herself and then washes her hands under a scalding tap. She tries to get some of the mud off. The stuff is caked beneath her fingernails, and after a few half-hearted attempt to rinse it away, she gives up. The mirror reveals an ashen face, red-rimmed eyes and cheeks smeared with brown dirt. It’s a face that is at once recognisable and yet wholly unfamiliar. She washes off the streaks of mud, uses a paper towel to wipe it dry, and leaves the bathroom.

Back under the strip-light glare of the shopping centre, she heads to the coffee kiosk, the scent of cinnamon and freshly brewed coffee mingling with the smell of recycled mall air. Normally Catriona would specify what coffee she would like – a skinny mocha something or other with a flavoured syrup and all that crap – but after standing in line for what seems like forever, her mind has gone blank.

‘Coffee please,’ she croaks.

‘Any particular one? Americano? Flat white?’ the girls asks.

‘Uh, just a white coffee,’ Catriona replies. She waits at the other end of the counter while another girl prepares it. Again, she’s aware of some kind of upbeat music being piped over the speakers, but it’s muffled like it’s underwater. Is that because the speaker system is faulty? Or could there be something wrong with her hearing? Either way, it doesn’t matter.

A mug is placed before her and she’s vaguely aware of the girl saying something friendly. Catriona doesn’t respond. She takes her coffee to a spare table in front of the play area, which consists of a small ball pit, a red-and-brown plastic playhouse and some climbing apparatus with wide tubes to crawl through and slide down. There are no children playing there and it has an oddly sad and neglected air. Catriona sits down and sips her drink. Stares at the familiar play area until her vision blurs. Of all the places to come, why has she come here? After today, this should be the last place on earth she would want to be.

There’s a bustle and clatter behind her as two women pushing designer prams arrive. They spend a couple of minutes loudly deciding where to sit, finally selecting a table by the water feature, hidden behind a couple of potted palm trees to Catriona’s right. They remove their outer layers – gloves, coats, scarves et cetera – draping them over the pram handles.

Catriona catches her breath as she notices a little toddler, previously hidden from view, behind one of the prams. The sweet little girl can’t be much more than two and a half years old. She’s chestnut-haired and round-cheeked with sparkling eyes and barely contained energy f

izzing out of her little body.

A slender dark-haired woman – presumably her mother – bends down and unzips her daughter’s white Puffa coat. The girl wriggles out of it. She’s dressed in branded pink leggings, a turquoise ballet skirt and a multicoloured top studded with tiny glittery hearts. On her feet she wears pink Uggs lined with sheepskin. Her outfit probably cost more than everything in Catriona’s wardrobe put together. The little girl runs over to the playhouse, opens the door and disappears inside, banging the door shut after her.

Over at their table, one of the mothers checks inside both prams and takes a seat while the other woman heads to the kiosk. The little girl peeks out of the playhouse window. She catches Catriona’s eye. Catriona smiles and gives the little girl a wave. The little girl waves back, bless her.

Catriona’s own heart suddenly begins to beat faster. So loud that it thumps in her ears, drowning out the mall music and the echoing chatter of the other customers. She takes a moment to breathe, but the thumping in her body won’t quiet down. Without thinking, she stands and walks back to the kiosk. Queues behind the mother who’s now selecting an assortment of pastries to go with their drinks. Catriona’s gaze sweeps across the cakes displayed behind the glass. They’re all too big, too grown-up and far too messy for a child to eat. She gives an inward smile as she spies just what she’s looking for in a large glass jar on top of the counter – a cookie in the shape of a rabbit, its long ears and small nose iced in pale pink. Perfect.

Catriona waits until the mother has finished ordering, and then she purchases the cookie along with a small chocolate bar to perk herself up – she’s starting to feel a little light-headed, realising she hasn’t eaten since breakfast. The girl behind the counter places the cookie on a small white plate on top of a napkin. This time, Catriona smiles at the girl and thanks her. She winds her way slowly back to her seat where her coffee is cooling on the table. She wants to act straight away but restrains herself. Instead, she sits back down, eats her chocolate and sips at her drink without tasting it, absent-mindedly picking dried mud from beneath split fingernails. Her heartbeat is still far louder than everything else around her. Its insistent thrumming helping to focus her mind on what she’s about to do.

Her face is warm now, her hands tingling, her head light and swimmy. But it’s almost a good feeling. It blocks out all the other stuff, dampens it down so it can’t be felt properly. Maybe it can all stay hidden way down there. Maybe she can squash it so small that it gets lost forever. Grains of dark grit floating endlessly down in a bottomless ocean.

The little girl waves at her again, emerging from the plastic house with a shy smile. Catriona glances over at the mothers, who are now deep in conversation, talking fast while shovelling pastries into their mouths and sucking down their frothy coffees. They’re seated too far away from the play area. If she were that little girl’s mother, she’d be sitting at the edge of the café with a direct view of her daughter. Not angled away and oblivious.

And yet, Catriona knows what it’s like to snatch a few minutes for yourself – that blissful illusion of freedom. When you’re out of the house talking to another grown-up person, let loose in the real world away from cleaning, cooking, toilet-training. Those moments when you remember who you were before becoming a mother. How luxurious it feels. How freeing. She shakes her head. Stupid woman. She’s probably been looking forward to this morning. Wishing for it. Meeting up with her friend. Hoping the babies stay asleep and her daughter remains occupied in the play area. But it just goes to show… you should be careful what you wish for.

The little girl is now exploring the rest of the play area – throwing the balls around the ball pit and crawling under the plastic tubes. Catriona’s heart is lodged in her gullet as she lurches to her feet, scraping the chair back too loudly. She glances back at the women, but they haven’t noticed her. Their heads are together as they chatter away. Laughing, and then serious again. The rise and fall of their voices merging with the mall sounds. Catriona makes her way around to the far side of the play area, the side nearest to the exit. She pulls up the hood of her sweatshirt, keeping her face angled low.

A voice in the background of her brain is yelling at her to stop this. To go back home and deal with it all. But a louder voice screams that this is the only way to stem the tidal wave of pain that’s threatening to drown her. It has to be fate that this beautiful little child is here right now. A dark-haired girl. A daughter.

‘Hello,’ she says softly to the child as she emerges from beneath one of the colourful tubes.

The girl smiles shyly.

‘Do you like bunny rabbits?’ Catriona holds out the biscuit and makes it do a funny little dance.

The girl giggles. A sound that makes Catriona want to sink to the ground and sob. Instead, she arranges her face into the warmest, most inviting smile she can create. ‘Would you like this one? Look – it’s got pink ears.’

The girl looks around, as though seeking approval from her mother. But the women are both hidden from view and neither of them are paying attention to the toddler.

‘Your mum said it was fine. She said you could come and see a real bunny rabbit. Would that be fun? You can stroke it and hold it, if you like.’

‘I got a toy bunny.’

‘Have you? Well mine is real – it’s white and fluffy and hops around the room. Here, have this biscuit bunny first, if you like.’ Catriona hands her the cookie.

The girl takes it, looks it up and down, then nibbles a corner.

‘Is it good?’

She nods twice and takes a bigger bite.

‘Want to come and see the real bunny now?’ Catriona holds out a hand, her pulse racing, the skin on her face suddenly hot while she waits for the child’s response.

‘What’s its name?’

‘Oh. Er, Mr Fluffy.’

‘That’s funny.’ The girl giggles and takes her hand. At once Catriona feels her shoulders relax. She turns and walks quickly, merging easily with the crush of other shoppers, the girl skipping along at her side, munching away on the rabbit cookie. Catriona pushes open the exit door and then makes her way back to her car.

‘Where’s the bunny?’ the girl asks.

‘We’re going to see it now. It’s just a short drive away, okay? How’s that bunny biscuit? Is it yummy?’

‘I like the pink bits.’

‘The icing?’

She nods.

Catriona opens the back door to the car. ‘Up you hop.’

‘Rabbits hop,’ the little girl says.

Catriona gives a little laugh. ‘Yes! Yes they do.’ Suddenly she knows everything is going to be okay. Coming here to the shopping mall was destined. The little girl is adorable.

She’s her little girl now. This was meant to be.

2

Now

I zip up my coat and shove my hands into my pockets. The afternoon is sunny and bright, but this part of the playground is always such a wind tunnel, spanning the length of the long, low red-brick building that houses all the classrooms. I stamp my feet to warm them. The school bell rang at least five minutes ago, but Jess and Charlie’s classes always seem to be the last ones out.

I jump at a tap on my shoulder. Thinking it must be a friend, I turn to find myself staring into a stranger’s eyes. An elegant blonde woman in her thirties, wearing a green Boden coat and a worried, apologetic expression. ‘Hi,’ I say. ‘Everything okay?’

‘Hello, sorry, I’m panicking a bit. It’s my children’s first day here. The bell went ages ago, but I can’t seem to see them. Just wondering if I’m waiting in the right spot?’

‘What year are they in?’ I ask.

‘Amy’s in year five and Kieran’s year two.’

‘Oh, same as my two. You’re fine. This is the right spot. We used to have to pick them up from different playgrounds, but it was such a mad dash that now they’ve combined pick-ups for the first and middle schools. Our year groups are always late coming out though. I�

��m Rachel, by the way. Rachel Farnborough.’ I stick out my hand and shake her leather-gloved one.

‘Oh, thanks. That’s a relief.’ The woman smiles. ‘I’m Kate Morris. Terrified newbie – in case you didn’t get that.’

‘Nice to meet you, Kate. And there’s nothing to be terrified about. We’re a pretty friendly bunch here at Wareham Park. So, what school were yours at before?’

‘We’ve just moved here from London.’

‘Wow, bit different to round here!’ I grin, feeling suddenly proud of the peace and quiet of our pretty Dorset town. I’ve only lived here for seven years, but it really does feel like home. Wareham is a gorgeous place, set on the River Frome, with pretty shops and eateries surrounded by lush green English countryside. I love London too, but the capital is as far removed from Wareham as you can get.

‘Just a bit,’ Kate replies. ‘But that’s why we moved here. We’ve had a few family holidays in Wareham over the years and fell in love with the place. Plus, life was getting too hectic in London and we aren’t keen on the senior schools where we lived. Amy is in year five, so we would have had to start thinking about all that again. The system’s different in London, and the Dorset one works better for us.’