The Republic of Thieves

Scott Lynch

The Republic of Thieves is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2013 by Scott Lynch

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Del Rey, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, New York, a Penguin Random House Company.

DEL REY and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Lynch, Scott

The Republic of Thieves / Scott Lynch.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-553-80469-0 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

ebook ISBN: 978-0-553-90558-8

1. Swindlers and swindling—Fiction. 2. Brigands and robbers—Fiction. 3. Man-woman relationships—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3612.Y5427R47 2013

813′.6—dc23

2013024809

www.delreybooks.com

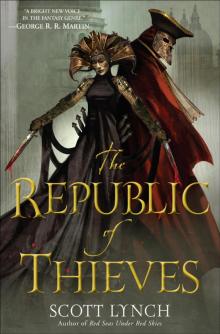

Jacket illustration: Benjamin Carré/Bragelonne

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Map

Prologue: The Minder

I: Her Shadow

Chapter One: Things Get Worse

Interlude: The Undrowned Girl

Chapter Two: The Business

Interlude: The Boy Who Chased Red Dresses

Intersect (I): Fuel

Chapter Three: Blood and Breath and Water

Interlude: Orphan’s Moon

Chapter Four: Across The Amathel

II: Cross-Purposes

Interlude: Striking Sparks

Chapter Five: The Five-Year Game: Starting Position

Interlude: Bastards Abroad

Chapter Six: The Five-Year Game: Change of Venue

Intersect (II): Tinder

Interlude: The Moncraine Company

Chapter Seven: The Five-Year Game: Countermove

III: Fatal Honesty

Interlude: Aurin and Amadine

Chapter Eight: The Five-Year Game: Infinite Variation

Interlude: Happenings in Bedchambers

Chapter Nine: The Five-Year Game: Reasonable Doubt

Intersect (III): Spark

Interlude: An Inconvenient Patron

Chapter Ten: The Five-Year Game: Final Approaches

Interlude: Death-Masks

Chapter Eleven: The Five-Year Game: Returns

Intersect (IV): Ignition

Last Interlude: Thieves Prosper

Chapter Twelve: The End of Old Dreams

Epilogue: Wings

Dedication

Afterword

Other Books by This Author

About the Author

PROLOGUE

THE MINDER

1

PLACE TEN DOZEN hungry orphan thieves in a dank burrow of vaults and tunnels beneath what used to be a graveyard, put them under the supervision of one partly crippled old man, and you will soon find that governing them becomes a delicate business.

The Thiefmaker, skulking eminence of the orphan kingdom beneath Shades’ Hill in old Camorr, was not yet so decrepit that any of his grimy little wards could hope to stand alone against him. Nonetheless, he was alert to the doom that lurked in the clutching hands and wolfish impulses of a mob—a mob that he, through his training, was striving to make more predatory still with each passing day. The veneer of order that his life depended on was insubstantial as damp paper at the best of times.

His presence itself could enforce absolute obedience in a certain radius, of course. Wherever his voice could carry and his own senses seize upon misbehavior, his orphans were tame. But to keep his ragged company in line when he was drunk or asleep or hobbling around the city on business, it was essential that he make them eager partners in their own subjugation.

He molded most of the biggest, oldest boys and girls in Shades’ Hill into a sort of honor guard, granting them shoddy privileges and stray scraps of near-respect. More important, he worked hard to keep every single one of them in constant deadly terror of himself. No failure was ever met with anything but pain or the promise of pain, and the seriously insubordinate had a way of vanishing. Nobody had any illusions that they had gone to a better place.

So he ensured that his chosen few, steeped in fear, had no outlet save to vent their frustrations (and thus enforce equivalent fear) upon the next oldest and largest set of children. These in turn would oppress the next weakest class of victim. Step by step the misery was shared out, and the Thiefmaker’s authority would cascade like a geological pressure out to the meekest edges of his orphan mass.

It was an admirable system, considered in itself, unless of course you happened to be part of that outer edge—the small, the eccentric, the friendless. In their case, life in Shades’ Hill was like a boot to the face at every hour of every day.

Locke Lamora was five or six or seven years old. Nobody knew for certain, or cared to know. He was unusually small, undeniably eccentric, and perpetually friendless. Even when he shuffled along inside a great smelly mass of orphans, one among dozens, he walked alone and he damn well knew it.

2

MEETING TIME. A bad time under the Hill. The shifting stream of orphans surrounded Locke like an unfamiliar forest, concealing trouble everywhere.

The first rule to surviving in this state was to avoid attention. As the murmuring army of orphans headed toward the great vault at the center of Shades’ Hill, where the Thiefmaker had called them, Locke flicked his glance left and right. The trick was to spot known bullies at a safe distance without making actual eye contact (nothing worse, the mistake of mistakes) and then, ever so casually, move to place neutral children between himself and each threat until it passed.

The second rule was to avoid responding when the first rule proved insufficient, as it too often did.

The crowd parted behind him. Like all prey animals, Locke had a honed instinct for approaching harm. He had enough time to wince preemptively, and then came the blow, sharp and hard, right between his shoulder blades. Locke smacked into the tunnel wall and barely managed to stay on his feet.

Familiar laughter followed the blow. It was Gregor Foss, years older and two stone heavier, as far beyond Locke’s powers of reprisal as the duke of Camorr.

“Gods, Lamora, what a weak and clumsy little cuss you are.” Gregor put a hand on the back of Locke’s head and pushed him along, still in full contact with the moist dirt wall, until his forehead bounced painfully off one of the old wooden tunnel supports. “Got no strength to stay on your own feet. Hell, if you tried to bugger a cockroach, the roach’d spin you round and do you up the ass instead.”

Everyone nearby laughed, a few from genuine amusement, the rest from fear of being seen not laughing. Locke kept stumbling forward, seething but silent, as though it were a perfectly natural state of affairs to have a face covered with dirt and a throbbing bump on the forehead. Gregor shoved him once more, but without vigor, then snorted and pushed ahead through the crowd.

Play dead. Pretend not to care. That was the way to keep a few moments of humiliation from becoming hours or days of pain, to keep bruises from becoming broken bones or worse.

The river of orphans was flowing to a rare grand gathering, nearly all the Hill, and in the main vault the air was already heavier and staler than usual. The Thiefmaker sat in his high-backed chair, his head barely visible above the press of children, while his oldest subjects carved paths through the crowd to take their accustomed places near him. Locke sought a far wall and pressed up agains

t it, doing his best impression of a shadow. There, with the welcome comfort of a guarded back, he touched his forehead and indulged in a momentary pout. His fingers were slippery with blood when he took them away.

After a few moments, the influx of orphans trickled to a halt, and the Thiefmaker cleared his throat.

It was a Penance Day in the seventy-seventh Year of Sendovani, a hanging day, and outside the dingy caves below Shades’ Hill the duke of Camorr’s people were knotting nooses under a bright spring sky.

3

“IT’S LAMENTABLE business,” said the Thiefmaker. “That’s what it is. To have some of our own brothers and sisters snatched into the unforgiving arms of the duke’s justice. Damned deplorable that they were slackards enough to get caught! Alas. As I have always been at pains to remind you, loves, ours is a delicate trade, not at all appreciated by those we practice upon.”

Locke wiped the dirt from his face. It was likely that his tunic sleeve deposited more grime than it removed, but the ritual of putting himself in order was calming. While he tended to himself the master of the Hill spoke on.

“Sad day, my loves, a proper tragedy. But when the milk’s gone bad you might as well look forward to cheese, hmm? Oh yes! Opportunity! It’s unseasonal fine hanging weather out there. That means crowds with spending purses, and their eyes are going to be fixed on the spectacle, aren’t they?”

With two crooked fingers (broken of old, and badly healed) he did a pantomime of a man stepping off an edge and plunging forward. At the end of the plunge the fingers kicked spasmodically and some of the older children giggled. Someone in the middle of the orphan army sobbed, but the Thiefmaker paid them no heed.

“You’re all going out to watch the hangings in groups,” he said. “Let this put fear into your hearts, loves! Indiscretion, clumsiness, want of confidence—today you’ll see their only possible reward. To live the life the gods have given you, you must clutch wisely, then run. Run like the hounds of hell on a sinner’s scent! That’s how we dodge the noose. Today you’ll have a last look at some friends who could not.

“And before you return,” he said, lowering his voice, “each of you will do them one better. Fetch back a nice bit of coin or flash, at all hazards. Empty hands get empty bellies.”

“Has we gots to?”

The voice was a desperate whine. Locke identified the source as Tam, a fresh catch, a lowest-of-the-low teaser who’d barely begun to learn the Shades’ Hill life. He must have been the one sobbing, too.

“Tam, my lamb, you gots to do nothing,” said the Thiefmaker in a voice like moldy velvet. He reached out and sifted through the crowd of orphans, parting them like dirty stalks of wheat until his hand rested on Tam’s shaven scalp. “But then, neither do I if you don’t work, right? By all means, remove yourself from this grand excursion. A limitless supply of cold graveyard dirt awaits you for supper.”

“But … can’t I, like, do something else?”

“Why, you could polish my good silver tea service, if only I had one.” The Thiefmaker knelt, vanishing briefly from Locke’s sight. “Tam, this is the job I got, so it’s the job you’re gonna do, right? Good lad. Stout lad. Why the little rivers from the eyes? Is it just ’cause there’s the hangings involved?”

“They—they was our friends.”

“Which means only—”

“Tam, you little piss-rag, stuff your whining up your stupid ass!”

The Thiefmaker whirled, and the new speaker recoiled from a slap to the side of his head. There was a ripple in the close-packed orphans as the unfortunate target stumbled backward and was returned to his feet by shoves from his tittering friends. Locke couldn’t suppress a smile. It always warmed his heart to see a bullying oldster knocked around.

“Veslin,” said the Thiefmaker with dangerous good cheer, “do you enjoy being interrupted?”

“N-no … no, sir.”

“How pleased I am to find us of a like mind on the subject.”

“Of … course. Apologies, sir.”

The Thiefmaker’s eyes returned to Tam, and his smile, which had evaporated like steam in sunlight a moment before, leapt back into place.

“As I was saying about our friends, our lamented friends. It’s a shame. But isn’t it a grand show they’re putting on for us as they dangle? A ripe plum of a crowd they’re summoning up? What sort of friends would we be if we refused to work such an opportunity? Good ones? Bold ones?”

“No, sir,” mumbled Tam.

“Indeed. Neither good nor bold. So we’re going to seize this chance, right? And we’re going to do them the honor of not looking away when they drop, aren’t we?”

“If … if you say so, sir.”

“I do say so.” The Thiefmaker gave Tam a perfunctory pat on the shoulder. “Get to it. Drops start at high noon; the Masters of the Ropes are the only punctual creatures in this bloody city. Be late to your places and you’ll have to work ten times as hard, I promise you. Minders! Call your teasers and clutchers. Keep our fresher brothers and sisters on short leashes.”

As the orphans dispersed and the older children called the names of their assigned partners and subordinates, the Thiefmaker dragged Veslin over to one of the enclosure’s dirt walls for a private word.

Locke snickered, and wondered whom he’d be partnered with for the day’s adventure. Outside the Hill there were pockets to be picked, tricks to be played, bold larceny to be done. Though he realized his sheer enthusiasm for theft was part of what had made him a curiosity and an outcast, he had no more self-restraint in that regard than he had wings on his back.

This half-life of abuse beneath Shades’ Hill was just something he had to endure between those bright moments when he could be at work, heart pounding, running fast and hard for safety with someone else’s valuables clutched in his hands. As far as his five or six or seven years had taught him, ripping people off was the greatest feeling in the whole world, and the only real freedom he had.

4

“THINK YOU can improve upon my leadership now, boy?” Despite his limited grip, the Thiefmaker still had the arms of a grown man, and he pinned Veslin against the dirt wall like a carpenter about to nail up a decoration. “Think I need your wit and wisdom when I’m talking out loud?”

“No, your honor! Forgive me!”

“Veslin, jewel, don’t I always?” With a falsely casual gesture, the Thiefmaker brushed aside one lapel of his threadbare coat and revealed the handle of the butcher’s cleaver he kept hanging from his belt. The faintest hint of blade gleamed in the darkness behind it. “I forgive. I remind. Are you reminded, boy? Most thoroughly reminded?”

“Indeed, sir, yes. Please …”

“Marvelous.” The Thiefmaker released Veslin, and allowed his coat to fall over his weapon once again. “What a happy conclusion for us both, then.”

“Thank you, sir. Sorry. It’s just … Tam’s been whining all gods-damned morning. He’s never seen anyone get the rope.”

“Once upon a time it was new to us all,” sighed the Thiefmaker. “Let the boy cry, so long as he plucks a purse. If he won’t, hunger’s a marvelous instructor. Still, I’m putting him and a couple other problems into a group for special oversight.”

“Problems?”

“Tam, for his delicacy. And No-Teeth.”

“Gods,” said Veslin.

“Yes, yes, the speck-brained little turd is so dim he couldn’t shit in his hands if they were stitched to his asshole. Nonetheless, him. Tam. And one more.”

The Thiefmaker cast a significant glance at a far corner, where a sullen little boy leaned with his arms folded across his chest, watching other orphans form their assigned packs.

“Lamora,” whispered Veslin.

“Special oversight.” The Thiefmaker chewed nervously at the nails of his left hand. “There’s good money to be squeezed out of that one, if he’s got someone keeping him sensible and discreet.”

“He nearly burnt up half the bloody city, sir.”

“Only the Narrows, which mightn’t have been missed. And he took hard punishment for that without a flinch. I consider the matter closed. What he needs is a responsible sort to keep him in check.”

Veslin was unable to conceal his expression of disgust, and the Thiefmaker smirked.

“Not you, lad. I need you and your little ape Gregor on distraction detail. Someone else gets made, you cover for ’em. And get back to me straightaway if anyone gets taken.”

“Grateful, sir, very grateful.”

“You should be. Sobbing Tam … witless No-Teeth … and one of hell’s own devils in knee-breeches. I need a bright candle to watch that crew. Go wake me up one of the Windows bunch.”

“Oh.” Veslin bit his cheek. The Windows crew, so called because they specialized in traditional burglary, were the true elite among the orphans of Shades’ Hill. They were spared most chores, habitually worked in darkness, and were allowed to sleep well past noon. “They won’t like that.”

“I don’t give a damn what they like. They don’t have a job this evening anyway. Get me a sharp one.” The Thiefmaker spat out a gnawed crescent of dirty fingernail and wiped his fingers on his coat. “Hell, fetch me Sabetha.”

5

“LAMORA!”

The summons came at last, and from the Thiefmaker himself. Locke padded warily across the dirt floor to where the master of the Hill sat whispering instructions to a taller child whose back was turned to Locke.

Waiting before the Thiefmaker were two other boys. One was Tam. The other was No-Teeth, a hapless twit whose beatings at the hands of older children had eventually given him his nickname. A sense of foreboding scuttled into Locke’s gut.

“Here we are, then,” said the Thiefmaker. “Three bold and likely lads. You’ll be working together on a special detail, under special authority. Meet your minder.”

The taller child turned.

She was dirty, as they all were, and though it was hard to tell by the pale silver light of the vault’s alchemical lanterns, she looked a little tired. She wore scuffed brown breeches, a long baggy tunic that at some distant remove had been white, and a leather flat cap over a tight kerchief, so that not a strand of her hair was visible.