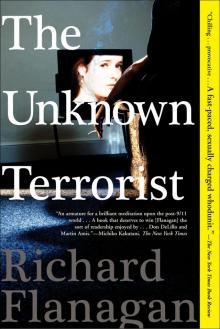

The Unknown Terrorist

Richard Flanagan

THE UNKNOWN TERRORIST

RICHARD FLANAGAN

Also by Richard Flanagan

Death of a River Guide

The Sound of One Hand Clapping

Gould’s Book of Fish

THE UNKNOWN TERRORIST

RICHARD FLANAGAN

Copyright © 2006 by Richard Flanagan

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation thereof, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

First published by in 2006 in Picador by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Limited

1 Market Street, Sydney

Printed in the United States of America

eBook ISBN-13: 978-1-5558-4836-1

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

For David Hicks

1

THE IDEA THAT LOVE IS NOT ENOUGH is a particularly painful one. In the face of its truth, humanity has for centuries tried to discover in itself evidence that love is the greatest force on earth.

Jesus is an especially sad example of this unequal struggle. The innocent heart of Jesus could never have enough of human love. He demanded it, as Nietzsche observed, with hardness, with madness, and had to invent hell as punishment for those who withheld their love from him. In the end he created a god who was “wholly love” in order to excuse the hopelessness and failure of human love.

Jesus, who wanted love to such an extent, was clearly a madman, and had no choice when confronted with the failure of love but to seek his own death. In his understanding that love was not enough, in his acceptance of the necessity of the sacrifice of his own life to enable the future of those around him, Jesus is history’s first, but not last, example of a suicide bomber.

Nietzsche wrote, “I am not a man, I am dynamite”. It was the image of a dreamer. Every day now somebody somewhere is dynamite. They are not an image. They are the walking dead, and so are the people who are standing round them. Reality was never made by realists, but by dreamers like Jesus and Nietzsche.

Nietzsche began to fear that what drove the world forward was all that was destructive and evil about it. In his writings he tried to reconcile himself to such a terrible world.

But one day he saw a cart horse being beaten brutally by its driver. He rushed out and put his arms around the horse’s neck, and would not let go. Promptly diagnosed as mad, he was locked away in an asylum for the rest of his life.

Nietzsche had even less explanation than Jesus for love and its various manifestations: empathy, kindness, hugging a horse’s neck to stop it being beaten. In the end Nietzsche’s philosophy could not even explain Nietzsche, a man who sacrificed his life for a horse.

But then, ideas always miss the point. Chopin could offer no explanation of his Nocturnes. Why the Doll was haunted by Chopin’s Nocturnes is one strand of this story. In listening to what Chopin could not explain, she heard an explanation of her own life. She could, of course, not know that it also foretold her own death.

SATURDAY

2

THE DOLL WAS A POLE DANCER. She was twenty-six, though routinely claimed, as she had been claiming since she was seventeen, to be twenty-two. A small, dark woman, her fine-featured face and almond eyes were set off by woolly black hair.

“Her body, hey,” said Jodie, a fellow pole dancer to whom the body mattered and who, at nineteen, was already a Botox junkie, “it wasn’t like, you know, contemporary. You know what I mean?” And everyone listening knew exactly what Jodie’s lack of expression meant.

The young women who flooded in and out of the pole dancing clubs were of every body type, but their bodies, whatever their differences, shared the toning that only hour after hour of swaying and swinging can bring and a diet of amphetamines and alcohol can hone. They aspired to an ideal they had seen starring in a hundred DVDs and a thousand video clips, splashed across an inestimable number of women’s magazine articles and gliding through a million ads. Hard and angular, bones and muscles rippling and bumps and products glistening, it was the ideal of beautiful women as cadaverous children.

But the Doll’s body seemed to belong to some different, older idea of what women were. In contrast to the muscled butts and thighs of the other dancers in the club, the Doll’s body was more rounded, her arms and thighs and buttocks fuller, and her movements were somehow similarly rounded and full.

She suspected her looks didn’t amount to much and did not trust the attention she felt they brought. She did not understand that the attention arose from something else, and that everything that she was—her slow movements, her smile, the way she engaged with people—was what attracted others even more than her looks. But she was twenty-six, pretending to be twenty-two, and looks mattered. She had an open, oval face. It was exactly the wrong face for our age.

3

If the Doll’s looks were exotic, her origins were everyday. She was a westie, though from which particular suburb no one knew. She was always going to leave the west, but she was surprised as a young woman how little she felt she had left behind. It wasn’t that she had no direction home, but that she had little sense she had ever had a home. The Doll had long ago determined that her early life would mean little to her, and she was of the fixed opinion that origins and explanations were not to be hers.

“I grew up like a cat, my friend,” she once told Jodie, who was no friend at all. “My family had no hand in it. You know any cats with an interest in family history?”

Of course, her father came from somewhere, and her mother from somewhere else, and their parents in turn must have had lives of some interest, lived in places and times that might even to our eyes seem exotic, the stuff of mini-series and fat novels discounted at Big W over Christmas; and the further one went back, no doubt the more intriguing it would all become: there might be notorious artists or famous criminals, failed businessmen or successful charlatans, people of variety and interest, of charm and horror. But if this were so, the Doll’s parents knew little of it and had interest in none of it. The pattern and passing of lives before and after them meant no more than the ebb and flow of traffic on the freeway.

Their world was one of suburban verities, their world was that of today: the house, the job, the possessions and the cars, the friends and the renovations, the resort holidays and the latest gadgets—digital cameras, home cinemas, a new pool. The past was a garbage bin of outdated appliances: the foot spa; the turbo oven; the doughnut maker and the record player, the SLR and the VCR and the George Foreman grill. The past was an embarrassment of distressing colours and styles about which to laugh: mullet haircuts and padded shoulders, top perms and kettle barbecues. Only this week’s catalogue was good and worth getting, no deposit and twenty-four months to pay. Their lives were empty, their lives they regarded as good. The Doll’s strongest memories were of television soaps.

She had watched Neighbours and Home and Away; she had been more upset at the age of eight by Daphne Lawrence dying than when her mother had split from her father the previous year, taking her two younger brothers with her to Hervey Bay to live with a fibreglass swimming pool installer called Ray. Then the Doll hadn’t known what was expected of her, or what was mean

t by such things; but Ramsay Street and Summer Bay made it clear: you cried and you laughed, you went on and on.

She watched music videos with the girls all beautiful and the men all fat and aggressive; the girls outshone the men, the way she saw it, with their looks and their dancing and the way they mostly didn’t bother saying anything while the men mouthed off—nothing could have prepared her better for pole dancing.

She claimed that the one enduring memory she had of her mother before she ran off was of a bad trompe l’oeil painting she had done on the Venetian blinds of their suburban lounge room. It was a picture of a window opening onto the sight of Bali’s Kuta Beach, where, on holiday, she had first met Ray.

For a time in her teens, she visited her mother in Hervey Bay occasionally. By then Ray had long gone, and her mother talked only of her two sons, two fat boys who dressed like two fat rappers, said Yo a lot and greeted each other American style, rubbing fist knuckles; it was as if the Doll were a new and not overly interesting neighbour across the street. Her mother’s life was another soap opera but a not particularly good one; a song cycle of drug problems, police visits, prolapses, and new partners. The visits to her mother oppressed the Doll. She went out of duty, and at some point duty seemed not much of a reason and she stopped going.

When, a few years later, she heard her mother had been killed in a pile-up on the Hume Highway she was sad, but not overly. It felt more like the confirmation of a long-standing absence than the beginning of one.

Perhaps the Doll told the story of her mother’s painting because the painting was for her about the stupidity of hope and holding on to dreams—or large dreams, in any case. Small dreams, small hopes, small things—all these and only these were what life permitted, and therefore to the Doll were permissible. Anything else, anything larger—as her mother’s life so graphically proved—could always be crushed. Which is not to say that the Doll was unhappy; on the contrary. She believed her acceptance of her life was what would guarantee her happiness. She would look straight into the Sydney sun, and never hide from it behind bad pictures of make-believe.

For the Doll was not a dreamer like Jesus or Nietzsche. Rather, she described herself as a realist. Realism is the embrace of disappointment, in order no longer to be disappointed.

4

“So I came to the city, my friend,” the Doll then told Jodie, “what of it?”

What of it, indeed? She no more understood her new world than she could explain her loathing and fear of her old, but what did it matter? In Sydney, the five or more millions of the westies detest the stinking snobbery of the north and the arrogance of the east, while the million or so of the rich north and east despise the grasping vulgarity and materialism of the poorer west. Nobody will admit they all think much the same, and that what moves and joins everyone in Sydney is one and the same thing: money; and nobody will admit that the only real difference is that up north and east they more or less have more, while out west they more or less have less.

The Doll wasn’t trying to understand any of this, and she would never try. She just wanted to get on, and explanations were simply so much more shit that the mugs talked when all they wanted was to see you with your knickers off.

“I got out of the west,” she would say in a nasal twang with its suggestion of Lebanese and Greek–Australian about the edges of its ululating vowels, “and I got the west out of me.”

It was untrue, like just about everything she said about herself. At the same time as harbouring a deep desire to one day live northside, she carried a chip on her shoulder about those who already did, and she could, simply because of the suggestion of an upper north shore address, quite gleefully open up on a customer as a snob and a wanker. Nothing could induce her to go further out from the central city than Newtown.

“It’s not good for the complexion, my friend,” she would say, as she would say about anything that made her sad, as though saying such a thing explained it all.

On the one hand she took an almost perverse pleasure in mocking other girls from the west for their overdone makeup, short skirts, big belts and the amount of product they plastered over their face and hair. On the other, in addition to her prejudices against west Sydney, the Doll had the average run of west Sydney prejudices about the rest of the world. She would on occasion give vent to being pissed off by slopeheads, dirty boongs, cops, and anyone reading the Sydney Morning Herald.

“I like to think I’m equally racist about everybody,” she would say, “but slimy Lebs I really hate.”

5

By the time the Doll got out of bed at ten, the day was already pleasantly hot. The steady traffic outside was the gentlest vibration inside her dark apartment. Her thoughts were too loose to describe. The contrast between the heaviness of her Temazepam-induced sleep and the lightness of the day further lifted the good mood in which she had woken. She gave herself over to what was immediate and likeable: that morning she felt a calm and a joy about the city, and this feeling so infected her she didn’t even bother dropping her customary Zoloft.

She caught a taxi to Bondi and as she rode between the tall buildings under a blue and brilliant sky, her eyes filled with tears: for no clear reason she felt happy and small happinesses she allowed herself.

At the beach she went swimming, lay on the sand, let herself fill with sun. She took pleasure in feeling her breasts spreading in the towelling beneath which the sand firmed; in smelling suntan oil and wet sand and air salty from the sea and acrid from the outfall sewage frothing to a latte on distant points.

As she turned her head sideways, one ear on the beach, one open to the sky, the roar of the waves became louder, the squeals of children a floating accompaniment that began to disappear as she lost her body and mind in the regular swoop and wash of the waves; it was a dream, a dream in which life was worth living after all.

Faraway, she could see a cloud, the only one in the sky. It looked like … but it didn’t really look like anything, just a slow-moving cloud, beautiful and alone. It kept changing, like the world, and, like the world, it was indescribable.

A nearby radio ran the same news it always seemed to run and its repetition of distant horror and local mundanity was calmly reassuring. More bombings in Baghdad, more water restrictions and more bushfires; another threat to attack Sydney on another al-Qa’ida website and another sportsman in another sex scandal, a late unconfirmed report that three unexploded bombs had been discovered at Sydney’s Homebush Olympic stadium and the heatwave was set to go on, continuing to set record highs, while here at the beach, waves rolled in, crashed, and rolled out again, taking all this irrelevant noise with them, as they always had, as they always would.

The radio said: “Live the dream!”

And wasn’t that just what she was doing?

There was nothing on earth she wanted at that moment, nothing she felt denied her that she wished to have, no ambition she felt unfulfilled. She desired neither friends nor a man, not money nor clothes nor to be other than who she was. The bad she had known seemed not important. Her body felt neither skinny nor fat, neither weary nor spent, nor excited, nor in need of exercise. She was not beautiful or ugly, but felt her body existed only to receive the gift of this life, and everything at that moment seemed good. It was enough to hear the waves crash and roll, to pour sand from one hand to the other and look at the falling grains.

The radio said: “Congratulations, Australia! We want to thank you with a knockdown sale on our bathroom accessories!”

She dozed, awoke, watched the beautiful surfies in their long boardies and the clubbies in their budgie smugglers, the gays with their tight bods, the girls with their muffin tops poking out proud as can be, the old men with tea bag bellies strutting, and the old women with bodies like weary pavs sagging in the heat, just sitting, watching; breasts and arses and wedding tackle all hanging in such wild disarray and the sun shining like there’s no tomorrow and over it all the waves returning the world to some other, better, larger

rhythm—who couldn’t feel happy as a bird and, as her friend Wilder would say, as free as a fart with all this?

And everything about the beach at that moment blended into something that seemed delightful and comforting, and the name the Doll gave it all was Sydney, and she felt she understood why many had come to love it so.

6

She was dozing when her phone rang. It was Wilder, saying she and Max were at Bondi, that it was a beautiful day, and why didn’t the Doll come and join them for a swim?

“It could take me a while,” the Doll said, standing, picking up her towel and bag, and scanning the beach, “what with the traffic and all.”

She began walking through the throngs of people and spotted the five-year-old Max digging a hole less than a hundred metres away, his mother Wilder lying next to him, majestic and brazen as ever, dark brown and topless.

The Doll rang Wilder back and asked her exactly where she was on the beach. As Wilder began issuing directions, the Doll snuck around behind her and continued talking, until her mouth was right up next to Wilder’s mobile phone. Wilder, who was in a splendid mood, turned, looked up with her unforgettable face and shrieked with delight. Max swung around in his hole and, on seeing the Doll, scrambled out and threw himself into her arms.

As the Doll cuddled and tickled Max, the two women chatted. Max soon grew bored and went back to his hole. Wilder told the Doll how she had been invited to be in a Mardi Gras float, Dykes with Dicks, that night. As far as the Doll knew, Wilder wasn’t a dyke, but Wilder said someone had taken ill and a friend had rung that very morning and asked her to make up the numbers. Last minute though it might have been, Wilder viewed it as an irresistible proposal, and now it was all arranged, with Max going to his father’s.