Trace the Stars

Nancy Fulda

A Hemelein Publications Original

Copyright © 2019 by Joe Monson and Jaleta Clegg. Except for brief excerpts in the case of reviews, this book may not be reproduced in any form without prior written permission of the publisher. All stories published by permission of the individual authors.

Story and content copyrights on page 307 at the end of this volume.

The stories in this book are works of fiction. Any names, characters, people, places, and events in these stories are products of the authors’ imaginations, and any resemblance to actual people, places, or events is entirely coincidental.

Published jointly by Hemelein Publications and LTUE Press as a benefit anthology for Life, the Universe, & Everything, an annual science fiction and fantasy academic symposium held in Provo, Utah. All proceeds help allow students to attend for a greatly reduced price. We appreciate your support.

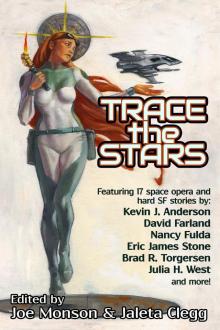

Cover artist: Kevin Wasden, http://kevinwasden.com/

Cover art, Tech Master, copyright © 2003 Kevin Wasden. Used by permission of the artist. Originally published on the cover of Spacemaster: Future Law (3rd Edition) from Iron Crown Enterprises, May 2003.

Editors: Joe Monson and Jaleta Clegg

Cover Design: Jaleta Clegg

Cover Design Assistance: Joe Monson

Associate Editors: Jeffrey Creer, Heather B. Monson

Interior Design: Marny K. Parkin

ISBN 978-1-64278-000-0 (trade paperback)

ISBN 978-1-64278-001-7 (ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number 2019900003

First Edition, February 2019

Hemelein Publications: http://hemelein.com/

LTUE Press: http://press.ltue.net/

LTUE Benefit Anthologies

Trace the Stars

A Dragon and Her Girl (forthcoming)

Edited by Joe Monson

Join the Space Force Now! (forthcoming)

Edited by Jaleta Clegg

Wandering Weeds: Tales of Rabid Vegetation (with Frances Pauli)

To Marion K. “Doc” Smith,

for inspiring so many of us to become more than we were.

You are remembered.

Contents

Foreword: Our Very Own Doc Smith

Angles of Incidence

Nancy Fulda

The Road Not Taken

Sandra Tayler

Log Entry

Kevin J. Anderson

The Ghost Conductor of the Interstellar Express

Brad R. Torgersen

A Veil of Leaves

M. K. Hutchins

Freefall

Eric James Stone

Launch

Daniel Friend

Glass Beads

Emily Martha Sorensen

Sweetly the Dragon Dreams

David Farland

Working on Cloud Nine

John M. Olsen

Fido

James Wymore

Knowing Me

Eric G. Swedin

Making Legends

Jaleta Clegg

Neo Nihon

Paul Genesse

The Last Ray of Light

Wulf Moon

Cycle 335

Beth Buck

Sea of Chaos

Julia H. West

Biographies

Acknowledgements

Foreword:

Our Very Own Doc Smith

The idea for Life, the Universe, & Everything was formed in 1982, when Ben Bova was invited to Brigham Young University by the English Department. English professor Marion K. “Doc” Smith was assigned to be Bova’s guest liaison in between official university events. He invited some of his students to hold what was later called a kaffeeklatsch with Bova, and this inspired those students to organize their own event in 1983. A tradition was born.

Since that time, thousands of students have attended and helped run the annual symposium. Many of them also worked on the Leading Edge, a semi-pro science fiction magazine created by many of those same students. Through the years, the annual symposium attendance has grown from a couple dozen to over 1,500 in 2018. During this growth, it has expanded from focusing only on writing and editing to include art, creating new worlds, academic papers on genre topics, creation of games of all sorts, short film festivals, and more.

LTUE has resisted changing into just another fan convention. In order to differentiate itself, it remained focused on the academic and professional side, and it is now one of the largest (if not the largest) academic science fiction and fantasy symposiums in North America. Many people at BYU (and outside of it) have helped the symposium over the years: Linda Hunter Adams, Zina Peterson, Betty Pope, Sue Ream, Sally Taylor, Marge Wight, and the list goes on. I became involved around the eighth year, chaired the event two weeks before getting married, and have maintained a strong connection to it ever since.

However, if you ask those who were around before LTUE began—and for the first several years—every one of them will tell you that Doc Smith was the main reason the symposium is still around. He helped get the initial funding. He helped keep funding (from different sources) through the years. He defended the symposium before unsympathetic faculty and administrators multiple times (ask me about the “gambling” incident sometime). He mentored everyone who worked on the symposium until his death in 2002. He always had a smile, a word of encouragement, and a helping hand anytime we needed it.

Therefore, I thought it only appropriate that the first of the LTUE Benefit Anthologies be dedicated to him. We will always appreciate his legacy, we still miss him, and we will do our best to make sure LTUE is always something he can be proud of.

Here’s to you, Doc! I hope you enjoy these stories as much as I did.

Joe Monson

February 2019

Angles of Incidence

Nancy Fulda

What are they?” Kitty asked.

The crystalline sculptures looked like gobs of lava halted mid-flow. There were thirty-five of them, spread about the room in a roughly circular pattern, each floating above a marble base and each about two meters tall.

“We don’t know,” said the refined—but annoying—man whose summons had destroyed a full afternoon’s opportunity to work. Two hours trapped in a stuffy gravrail compartment, shooting across the blank desert of Kokkal IV, unable even to link with the computer aboard her docilely orbiting jumpship. Agony, at least from Kitty’s perspective. If the urgently blinking message had come from anyone except the ruling eighth-minister of the planet’s human contingent, she would have conveniently pretended she hadn’t received it.

The elaborately dressed eighth-minister—his surname was Kahihatan—paused to finger the smoky amber glow of the nearest statue. Irritation colored his voice. “We were told only that the natives will not allow us to speak with the Evermother until we have ‘assimilated the shadows’. Their words, not mine. And without the Blind Queen’s authorization, there will be no joint habitation on the northern continent and no subsequent export of Kokkal IV’s biological crystals to offworld investors. Miss Kittyhawk—”

“Please, just call me Kitty.”

“Kitty.” The word sounded distasteful in his mouth. “I cannot emphasize how important this export deal is to the cultural development of our society.”

Translation: I’m several trillion credits in debt and the voters will eviscerate me if I don’t fix this. Kitty resisted the urge to roll her eyes.

“You do realize,” she said, slowly parading along the row of sculptures, “that I’m a xenoarchaeologist, not a galactic linguist or an astroanthropologist?”

“I fail to see the distinction.”

“Well, the biggest one is that I work with dead things.” Beautiful, intriguing dead things, like the elusi

ve remains of Kokkal’s extinct third species. To the excavation of which Kitty was aching to return. “Don’t you have cultural experts for this sort of thing? These statues clearly contain a message of some kind. Decode the message, and the problem is solved.”

Kahihatan waved a dismissive hand. “Our analysts have exhausted all possibilities. Sound shadows. Light beams projected through the sculptures. Magnetic resonance imaging.”

“Well, if they’ve exhausted all of the possibilities, then there’s really no reason for me to be here.”

The eighth-minister conveniently ignored this observation. “As far as we can tell,” he said briskly, “the sculptures are cheap hunks of polymer suspended in antigrav fields. They contain no hidden compartments and no subtle molecular encodings. They’re not even difficult to manufacture.”

“So it’s a test.”

“Or a linguistic barrier.” Kahihatan sounded exasperated. “We get those all the time. Communication with the Kokkalns works pretty well on mundane topics, but it falls apart at the abstract level. During the inauguration of my predecessor, the Blind Queen’s staff kept insisting that the seventh-minister’s clothes were too bright. We tried everything: black robes, white on beige, neutral brown. We nearly suggested that he appear naked.”

Now there was an appalling thought. “And?” Kitty prompted, hoping to move past the topic quickly.

“As it turned out, their objection had nothing to do with fabric color.” The eighth-minister shook his head in deprecation. “It was his chain of office. We’d commissioned a new design, you see, and our out-of-system manufacturer included a communications relay for security purposes. We didn’t realize it was active.”

Kitty winced. Ah, yes, that would do it. The Kokkalns were infamously sensitive to radio and other low-frequency wavelengths, which was why Kitty had been denied contact with her ship while riding the shared-species gravtrain. To Kokkaln senses, the broad-spectrum pings emitted by a communications relay must have been garishly painful.

“Be that as it may,” Kahihatan continued, “we’ve run out of ideas. So when we heard you were working on the Ll’tanii rehydration chambers along the wastelands . . . Well. They say you’re the best.”

“Yeah, well, they say a lot of things.” Kitty strolled again along the sculptures. Thirty-five of them, arrayed in a circle. No two alike. She sighed and admitted, “In this case, however, they’re probably right.”

“We’ll pay you for your time, of course.”

“I doubt you could afford it.” I don’t want money. I don’t want this job at all. Kitty would have walked out, if Kahihatan hadn’t held authority to revoke her excavation license.

Blasted politicians.

The eighth-minister said primly: “If we set up an export chain for biological crystal, we can afford almost anything.” Kitty waved a hand to shut him up.

“Fine. Have your goons find me a hotel or something. I’ll see what I can do.”

“You honor the Ministerial Government, Miss Kittyhawk.”

Kitty doubted the eighth-minister would appreciate a detailed account of what she would have liked to do with said government, so she prudently remained silent. She’d been on a lot of planets, some of them exceptionally well-run. Kokkal IV showed no signs of ever having belonged to that group.

She walked another circuit along the floating statues. No two had the same shape, and yet there was a nagging uniformity about them, as though they’d all been generated by the same algorithm. No, Kitty decided, it was more than that. It was as though they were all parts of the same whole.

Assimilate the shadows. The Kokkalns’ mysterious directive made no more sense to her than it did to Kahihatan. Although, the statues were casting shadows. Several each, due to the half-dozen unidirectional lights set into the ceiling. But why those shadows should be important, and how one should assimilate them, remained elusive.

“I’ll need to speak with the Evermother’s executives,” Kitty said, cringing inwardly. Live aliens were neither her passion nor her specialty. She had a habit of offending them, and they had a habit of, subsequently, attempting to consume her. Either that, or they tried to vaporize the human settlements with which she was associated.

Kitty sighed and consciously refrained from banging her head against one of the statues.

Really, she got along so much better with dead things.

Kokkal IV’s gravtrains resembled giant segmented worms made of overlapping metal plates. The Kokkalns had been using them, or similar designs, for centuries, and very happily so, before the human settlers arrived and began complaining about earthquakes. There had been a seventy-year squabble, Kitty was given to understand, resulting in a 500-page handbook on seismically responsible gravitic manipulation, which the Kokkalns had proceeded to ignore. Fortunately, surface architecture had by then become optimized for shock absorption.

“How is it,” Kitty asked as the gravtrain doors hissed closed, “that humans have been living on Kokkal IV for almost two hundred years, and yet no one’s ever spoken with the Evermother?”

“It hasn’t come up before,” Kahihatan said in a faintly peeved tone. He crammed into the transportation compartment along with his considerable entourage of aides, secretaries, political hangers-on and security personnel, who alternately jostled for seats and eyed the pungent Kokkaln passengers with distaste. Kitty, crammed between an iron support rail and the rough outer wall, couldn’t help thinking that the Kokkalns, lounging atop one another on the other side of the compartment, appeared far more comfortable than the stiffly-perpendicular humans. They also resembled a platter of oversized seafood, but Kitty hoped no one had ever mentioned that aloud.

“It hasn’t come up?” Kitty asked pointedly.

Kahihatan cleared his throat uncomfortably. “When we built the first geothermic shafts, the Blind Queen’s aides simply asked for a copy of our architectural schematics. When we requested rescue crews after the fourth-ministerial subterranean calamity, her aides didn’t even consult her. And back when humans first landed on Kokkal IV, nobody thought to ask permission. The Kokkalns were pretty miffed about that, for a few decades.”

Kitty, who’d been gulping a swig from her water bottle, nearly sputtered.

Miffed. Now there was the euphemism of the century. Humans and Kokkalns had, in fact, slaughtered each other on sight until second-minister Shallans managed to hammer out a linguistic common ground. Such as it was.

Kokkal IV, Kitty decided as the gravtrain pulled out of the station, was not so much a world at peace as it was a stunningly disjointed ecology. The russet-plated, vaguely crustacean Kokkalns resided in a vast network of subterranean water pockets that riddled the planet’s upper mantle. They had little interest in surface ecology beyond scientific research and the occasional spawning expedition. The planet’s human occupants were likewise unimpressed by the aqueous mantle pockets.

The result was a fragile equilibrium: Two co-habiting species, biologically disparate to the point of mutual incomprehensibility, who got along primarily by ignoring each other. A match made in heaven. Or thereabouts.

Kitty’s head was beginning to hurt. “Explain to me again,” she said to Kahihatan, “why you want to establish a settlement on the northern continent? You’re only occupying 15% of this one.”

“Because,” Kahihatan said with the air of an exasperated parent, “Kokkal IV’s native biological crystals do not grow well in arid southern environments. We’ve tried transplanting them. Believe me, we’ve tried! Specialized greenhouses, localized weather manipulation. Nothing works.”

“So,” Kitty said, following the thread to its conclusion, “if you want to establish the crystals as a major export product, you will need to cultivate and harvest them in the northern hemisphere.”

“Exactly. Which would require local scientists. Support staff. Basically, an independently functioning colony.”

“I don’t understand. Kokkalns are utterly indifferent to surface politics. They hardly even

venture above the third or fourth sublevel. Why would a second human colony be a problem?”

“Because it’s a spawning expedition. By Kokkaln terms, anyway. Spawning is very important to them, you see, and falls directly within the Blind Queen’s jurisdiction.”

Kitty tried to wrap her head around this, failed, and filed it away in the mental box labeled weird alien customs. “Ah,” she said sagely.

The train clattered downward, twisting and dipping in ways thought to be artistic to a Kokkaln’s spatial sensitivities. Kitty, long accustomed to hyperspace distortions, found the ensuing sensations rather prosaic. Judging from the insufficiently muffled moans, Kahihatan and his aides were less fortunate.

“So,” Kitty prompted once the train hit a steady patch, “You require the Blind Queen’s approval for your ‘spawning expedition’, but the Blind Queen refuses to speak to you until after you’ve, um, assimilated the shadows.”

“That’s right.” Kahihatan gulped an anti-nausea pill. “It’s a nightmare! Do you know how much funding we have tied up in preparations for the new colony?”

“Honestly? I don’t care.”

“Or how many jobs it will create?”

“I don’t quite see—” Kitty was going to say how that’s relevant, but was cut off as the train dropped into another spiral descent. She tried to map the pathways in her mind, corkscrews followed by staggered ramps, but quickly lost track. For Kokkaln parietal cortexes, which reputedly were capable of visualizing fourteen dimensions at once, it was probably the equivalent of pleasant elevator music.

Kahihatan moaned and gripped the support rails.

The gravtrain screeched, decelerated, and jerked to a halt at the first transfer station. Kahihatan and his aides gasped for breath, grumbling loudly about Kokkaln aesthetics. Kitty refrained from mentioning that the planet’s human contingent was welcome to build its own tunnel network. Not only would it send Kahihatan into another soliloquy on finances, but she wasn’t sure human tech could even penetrate to these depths. They were at the second sublevel now; the air was sticky and Kahihatan’s aides were already fastening respirators over their faces.