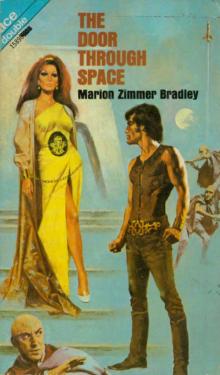

The Door Through Space

Marion Zimmer Bradley

Produced by Gregory D. Weeks, Jason Isbell, Irma Speharand the Online Distributed Proofreading Team athttps://www.pgdp.net

=THE DOOR THROUGH SPACE=

Marion Zimmer Bradley

ACE BOOKSA Division of Charter Communications Inc.1120 Avenue of the AmericasNew York, N.Y. 10036

THE DOOR THROUGH SPACE

Copyright (c), 1961, by Ace Books, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

... _across half a Galaxy, the Terran Empire maintains its sovereigntywith the consent of the governed. It is a peaceful reign, held bycompact and not by conquest. Again and again, when rebellion threatensthe Terran Peace, the natives of the rebellious world have turnedagainst their own people and sided with the men of Terra; not from fear,but from a sense of dedication._

_There has never been open war. The battle for these worlds is fought inthe minds of a few men who stand between worlds; bound to one world byinterest, loyalties and allegiance; bound to the other by love._

_Such a world is Wolf. Such a man was Race Cargill of the Terran SecretService._

* * * * *

RENDEZVOUS ON A LOST WORLDCopyright (c), 1961, by Ace Books, Inc.

Printed in U.S.A.

* * * * *

=Author's Note:--=

I've always wanted to write. But not until I discovered the old pulpscience-fantasy magazines, at the age of sixteen, did this generaldesire become a specific urge to write science-fantasy adventures.

I took a lot of detours on the way. I discovered s-f in its golden age:the age of Kuttner, C.L. Moore, Leigh Brackett, Ed Hamilton and JackVance. But while I was still collecting rejection slips for my earlyefforts, the fashion changed. Adventures on faraway worlds and strangedimensions went out of fashion, and the new look inscience-fiction--emphasis on the _science_--came in.

So my first stories were straight science-fiction, and I'm not trying toput down that kind of story. It has its place. By and large, the kind ofscience-fiction which makes tomorrow's headlines as near as thismorning's coffee, has enlarged popular awareness of the modern,miraculous world of science we live in. It has helped generations ofyoung people feel at ease with a rapidly changing world.

But fashions change, old loves return, and now that Sputniks clutter upthe sky with new and unfamiliar moons, the readers of science-fictionare willing to wait for tomorrow to read tomorrow's headlines. Onceagain, I think, there is a place, a wish, a need and hunger for thewonder and color of the world way out. The world beyond the stars. Theworld we _won't_ live to see. That is why I wrote THE DOOR THROUGHSPACE.

--MARION ZIMMER BRADLEY

* * * * *

CHAPTER ONE

Beyond the spaceport gates, the men of the Kharsa were hunting down athief. I heard the shrill cries, the pad-padding of feet in strides justa little too long and loping to be human, raising echoes all down thedark and dusty streets leading up to the main square.

But the square itself lay empty in the crimson noon of Wolf. Overheadthe dim red ember of Phi Coronis, Wolf's old and dying sun, gave out apale and heatless light. The pair of Spaceforce guards at the gates,wearing the black leathers of the Terran Empire, shockers holstered attheir belts, were drowsing under the arched gateway where thestar-and-rocket emblem proclaimed the domain of Terra. One of them, asnub-nosed youngster only a few weeks out from Earth, cocked aninquisitive ear at the cries and scuffling feet, then jerked his head atme.

"Hey, Cargill, you can talk their lingo. What's going on out there?"

I stepped out past the gateway to listen. There was still no one to beseen in the square. It lay white and windswept, a barricade ofemptiness; to one side the spaceport and the white skyscraper of theTerran Headquarters, and at the other side, the clutter of lowbuildings, the street-shrine, the little spaceport cafe smelling ofcoffee and _jaco_, and the dark opening mouths of streets that rambleddown into the Kharsa--the old town, the native quarter. But I was alonein the square with the shrill cries--closer now, raising echoes from theenclosing walls--and the loping of many feet down one of the dirtystreets.

Then I saw him running, dodging, a hail of stones flying round his head;someone or something small and cloaked and agile. Behind him thestill-faceless mob howled and threw stones. I could not yet understandthe cries; but they were out for blood, and I knew it.

I said briefly, "Trouble coming," just before the mob spilled out intothe square. The fleeing dwarf stared about wildly for an instant, hishead jerking from side to side so rapidly that it was impossible to geteven a fleeting impression of his face--human or nonhuman, familiar orbizarre. Then, like a pellet loosed from its sling, he made straight forthe gateway and safety.

And behind him the loping mob yelled and howled and came pouring overhalf the square. Just half. Then by that sudden intuition whichpermeates even the most crazed mob with some semblance of reason, theycame to a ragged halt, heads turning from side to side.

I stepped up on the lower step of the Headquarters building, and lookedthem over.

Most of them were _chaks_, the furred man-tall nonhumans of the Kharsa,and not the better class. Their fur was unkempt, their tails naked withfilth and disease. Their leather aprons hung in tatters. One or two inthe crowd were humans, the dregs of the Kharsa. But the star-and-rocketemblem blazoned across the spaceport gates sobered even the wildestblood-lust somewhat; they milled and shifted uneasily in their half ofthe square.

For a moment I did not see where their quarry had gone. Then I saw himcrouched, not four feet from me, in a patch of shadow. Simultaneouslythe mob saw him, huddled just beyond the gateway, and a howl offrustration and rage went ringing round the square. Someone threw astone. It zipped over my head, narrowly missing me, and landed at thefeet of the black-leathered guard. He jerked his head up and gesturedwith the shocker which had suddenly come unholstered.

The gesture should have been enough. On Wolf, Terran law has beenwritten in blood and fire and exploding atoms; and the line is drawnfirm and clear. The men of Spaceforce do not interfere in the old town,or in any of the native cities. But when violence steps over thethreshold, passing the blazon of the star and rocket, punishment isswift and terrible. The threat should have been enough.

Instead a howl of abuse went up from the crowd.

"_Terranan!_"

"Son of the Ape!"

The Spaceforce guards were shoulder to shoulder behind me now. Thesnub-nosed kid, looking slightly pale, called out. "Get inside thegates, Cargill! If I have to shoot--"

The older man motioned him to silence. "Wait. Cargill," he called.

I nodded to show that I heard.

"You talk their lingo. Tell them to haul off! Damned if I want toshoot!"

I stepped down and walked into the open square, across the crumbledwhite stones, toward the ragged mob. Even with two armed Spaceforce menat my back, it made my skin crawl, but I flung up my empty hand in tokenof peace:

"Take your mob out of the square," I shouted in the jargon of theKharsa. "This territory is held in compact of peace! Settle yourquarrels elsewhere!"

There was a little stirring in the crowd. The shock of being addressedin their own tongue, instead of the Terran Standard which the Empire hasforced on Wolf, held them silent for a minute. I had learned that longago: that speaking in any of the languages of Wolf would give me aminute's advantage.

But only a minute. Then one of the mob yelled, "We'll go if you give'mto us! He's no right to Terran sanctuary!"

I walked over to the huddled dwarf, miserably trying to make himselfsmaller against the wall. I nudged him with my foot.

"Get up. Who are you?"

The hood fell away from his face as he twitc

hed to his feet. He wastrembling violently. In the shadow of the hood I saw a furred face, aquivering velvety muzzle, and great soft golden eyes which heldintelligence and terror.

"What have you done? Can't you talk?"

He held out the tray which he had shielded under his cloak, an ordinarypeddler's tray. "Toys. Sell toys. Children. You got'm?"

I shook my head and pushed the creature away, with only a glance at thearray of delicately crafted manikins, tiny animals, prisms and crystalwhirligigs. "You'd better get out of here. Scram. Down that street." Ipointed.

A voice from the crowd shouted again, and it had a very ugly sound. "Heis a spy of Nebran!"

"_Nebran--_" The dwarfish nonhuman gabbled something then doubledbehind me. I saw him dodge, feint in the direction of the gates, then,as the crowd surged that way, run for the street-shrine across thesquare, slipping from recess to recess of the wall. A hail of stoneswent flying in that direction. The little toy-seller dodged into thestreet-shrine.

Then there was a hoarse "Ah, aaah!" of terror, and the crowd edged away,surged backward. The next minute it had begun to melt away, its entitydissolving into separate creatures, slipping into the side alleys andthe dark streets that disgorged into the square. Within three minutesthe square lay empty again in the pale-crimson noon.

The kid in black leather let his breath go and swore, slipping hisshocker into its holster. He stared and demanded profanely, "Where'd thelittle fellow go?"

"Who knows?" the other shrugged. "Probably sneaked into one of thealleys. Did you see where he went, Cargill?"

I came slowly back to the gateway. To me, it had seemed that he duckedinto the street-shrine and vanished into thin air, but I've lived onWolf long enough to know you can't trust your eyes here. I said so, andthe kid swore again, gulping, more upset than he wanted to admit. "Doesthis kind of thing happen often?"

"All the time," his companion assured him soberly, with a sidewise winkat me. I didn't return the wink.

The kid wouldn't let it drop. "Where did you learn their lingo, Mr.Cargill?"

"I've been on Wolf a long time," I said, spun on my heel and walkedtoward Headquarters. I tried not to hear, but their voices followed meanyhow, discreetly lowered, but not lowered enough.

"Kid, don't you know who he is? That's Cargill of the Secret Service!Six years ago he was the best man in Intelligence, before--" The voicelowered another decibel, and then there was the kid's voice asking,shaken, "But what the hell happened to his face?"

I should have been used to it by now. I'd been hearing it, more or lessbehind my back, for six years. Well, if my luck held, I'd never hear itagain. I strode up the white steps of the skyscraper, to finish thearrangements that would take me away from Wolf forever. To the other endof the Empire, to the other end of the galaxy--anywhere, so long as Ineed not wear my past like a medallion around my neck, or blazoned andbranded on what was left of my ruined face.