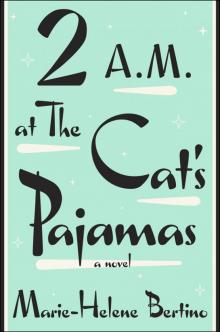

2 a.m. at the Cat's Pajamas

Marie-Helene Bertino

Also by Marie-Helene Bertino

Safe as Houses

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2014 by Marie-Helene Bertino

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Blossom Dearie Music for permission to reprint an excerpt from “Blossom’s Blues,” copyright © 1956 by Blossom Dearie Music. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission of Blossom Dearie Music, as administered by Jim DiGionvanni.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bertino, Marie-Helene.

2 A.M. at The Cat’s Pajamas : a novel /

Marie-Helene Bertino.—First edition.

pages cm

I. Title. II. Title: Two A.M. at The Cat’s Pajamas.

PS3602.E7683A33 2014

813’.6—dc23 2013048943

ISBN 978-0-8041-4023-2

eBook ISBN 978-0-8041-4024-9

Jacket design by Christopher Brand

v3.1

Mom,

You said, some people invest in prizefighters, I’ll invest in you. It was one of those gray nights when (everyone took the easy way out) I did not feel strong. This book is for you (Helene Bertino), for turning me into a prizefighter, with grace.

“Yes, [Philadelphia is] horrible, but in a very interesting way. There were places there that had been allowed to decay, where there was so much fear and crime that just for a moment there was an opening to another world.”

—DAVID LYNCH

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

7:10 A.M.

7:15 A.M.

7:30 A.M.

8:00 A.M.

9:00 A.M.

10:00 A.M.

10:30 A.M.

11:10 A.M.

11:30 A.M.

12:30 P.M.

1:00 P.M.

2:00 P.M.

3:00 P.M.

3:05 P.M.

3:30 P.M.

4:00 P.M.

5:00 P.M.

5:15 P.M.

6:00 P.M.

6:30 P.M.

6:40 P.M.

6:45 P.M.

7:00 P.M.

10:00 P.M.

10:05 P.M.

10:06 P.M.

10:10 P.M.

10:50 P.M.

11:00 P.M.

11:05 P.M.

11:10 P.M.

11:11 P.M.

Midnight

12:10 A.M.

12:15 A.M.

12:30 A.M.

12:42 A.M.

12:41 A.M.

12:40 A.M.

12:39 A.M.

12:43 A.M.

1:00 A.M.

1:20 A.M.

1:26 A.M.

1:30 A.M.

1:35 A.M.

1:40 A.M.

1:43 A.M.

1:45 A.M.

1:45 A.M.

1:46 A.M.

1:58 A.M.

1:59 A.M.

1:59 A.M.

1:59 A.M.

2:00 A.M.

2:00 A.M.

2:00 A.M.

2:01 A.M.

2:30 A.M.

3:15 A.M.

4:00 A.M.

4:20 A.M.

6:30 A.M.

Acknowledgments

It is dark, dark seven A.M. on Christmas Eve Eve.

Snow flurries fall in the city. Actors walking home from a cast party on Broad Street try to catch them on their tongues. The ingénue lands a flake on her hot cheek and erupts into a fit of laughter. In Fishtown a nightmare trembles through the nose and paws of a dog snoozing under construction flats. The Rittenhouse Square fountain switches to life with a pronouncement of water while Curtis Hall musicians, late for final rehearsal, arpeggiate through the park.

The flurries somersault, reconsider, double back. The Ninth Street alleys bear witness as they softly change their minds. Mrs. Rose Santiago, shawl knotted beneath her chin, uses a broom to convince them away from her stoop. They refuse to land. She sweeps uselessly at the air.

In her room at the prow of her father’s apartment, Madeleine Altimari practices the shimmy. Shoulders, shoulders, shoulders. In front of the mirror, so she can judge herself, face sharp with focus. It is the world’s most serious shimmy. After thirty seconds, a flamingo-shaped timer trills and hops on its plastic legs. Madeleine stops shimmying and rejoins a Menthol 100 dozing in an ashtray on her vanity.

She exhales. “Again.”

On the record player, Blossom Dearie says she’s alive, she’s awake, she’s aware. Shoulders, shoulders, shoulders. After thirty seconds, the timer trills again.

Madeleine frowns at herself in the mirror. “Terrible.” On a list by the ashtray, she marks one minute next to The Shimmy, followed by a pert C minus. She drags on the cigarette. The other categories—Singing, Scales, Guitar—are unmarked.

Madeleine is two days away from being ten.

She wears a clothespin on her nose and the uniform for Saint Anthony of the Immaculate Heart: a maroon sweater over a gray jumper over a gold shirt over a training bra with lemon-colored stitching. Thick, maroon tights. She is number three in fifth-grade height-ordered lineups, behind Maisie, whose spine is shaped like a question mark, and Susan, the daughter of ballerinas. She read somewhere a clothespin worn religiously will shrink her unignorable nose. She thinks the occasional glimmers she can see through her window are snow flurries. She has trouble spelling the word rhythm. She likes when people in movies go to see movies. She cannot understand why the dime is worth more than the fatter, wider nickel. She needs a haircut. Her favorite singer is Blossom Dearie and her favorite bass is upright. She spent the previous night dreaming of apples. She smokes Newport Menthols from the carton her mother was smoking when she died the previous year.

Eggs cuss and snap on the kitchen stove.

The unofficial rule of Saint Anthony of the Immaculate Heart is that Madeleine is never allowed to sing again in church or at any assembly. Never, never, a whole page of nevers. Even though she had nothing to do with what happened at the previous year’s Winter Assembly. Still, it is going to be a gold star day. She will suffer through Clare Kelly’s singing in morning mass, the girl’s nasal notes and plosive p’s filling the church with godless noise, spritzing the first row of pews with every heretical t, BUT THEN, her class will be making caramel apples. Madeleine has never had a caramel apple and she wants to taste one more than she wants God’s love.

Clare, the sound Madeleine’s toilet makes when it’s dry. Madeleine is forever adding water to its basin when it wails, from the purpose-specific can she keeps under the sink.

Like a comet, a horrific afterthought, a roach darts down the wall. Its path follows indecipherable logic. Madeleine screams in high C and crushes the cigarette. She pivots, rips a paper towel from a roll on her nightstand. The roach halts, teasing coordinates out of the air with its antennae. It senses her and is rendered paralyzed by options. Madeleine closes her eyes, makes the sound of a train whistle on a prairie, and squeezes. Ninth Street Market roaches are full and round like tomatoes. This one leaves a m

ark on the wall but most of it gets flushed down the toilet. She scrubs her hands. Breathes in and out. Every day, more and more roaches. Every time she kills one, Madeleine worries she is a bad person. Stop worrying, she instructs herself. It’s time to sing.

She changes the record and releases the clothespin from her nose. She locks eyes with herself in the mirror and waits for the music to start.

Madeleine sings.

My name is Blossom

I was raised in a lion’s den.

One hand is perched on her hip while the other swings back and forth, keeping time. Tucked into the mirror of her vanity, a picture of her mother singing: one hand on her hip, the other swinging back and forth, in time. Her mother was a dancer and singer whose voice could redirect the mood of a room.

My nightly occupation

Is stealing other women’s men.

After the cancer spread to her lymph nodes, Madeleine’s mother filled a recipe box with instructions on how to do various things she knew she wouldn’t be around to teach her. HOW TO MAKE A FIST, HOW TO CHANGE A FLAT, HOW TO WRITE A THANK-YOU NOTE FOR A GIFT YOU HATE, HOW TO BE EFFICIENT: Whenever you are doing one thing, ask yourself: what else could I be doing? On one recipe card, Madeleine’s mother listed the rules of singing.

The #1 rule: KNOW YOURSELF.

Madeleine knows she frowns in the silence between lines. She knows if she straightens her spine she can hit more notes than if she hunches. She knows she makes up in full-throatedness what she lacks in technical ability. She knows how to harmonize, with anything, with someone talking, that harmony is what melody carries in its pocket. She can burrow into a line of music and search out unexpected melodies. She can scat. She knows she scats better if she has eaten a light breakfast. She knows an empty orb hovers inside her, near where the ovaries are drawn on the foldout in her health textbook: the diaphragm. In the diaphragm, the weather is always seventy degrees and sunny. Unable to be shaken even when she shakes. Madeleine has trained herself to, when she falters on a high note, clasp the reins of her diaphragm and gather.

The song is over. In her flamingo notebook, Madeleine marks Blossom’s Blues next to Singing. The scatting was flat but had soul. B minus, she writes.

The eggs are ready. She slides them onto a plate and adds a square of toast and a spoonful of jam. She holds her breath as she steps into her father’s bedroom. He is sleeping, his back toward her. She clears medicine bottles, an ashtray, a half-empty glass of water, to make space for the plate on his dresser.

Normally she leaves his breakfast and skedaddles, however this morning she wants to feel close to something. She places her hand on his arm. It moves up and down in sleep. Madeleine breathes in and out, in time.

“Eggs,” she whispers.

In her bedroom, she peers through the curtains to confirm that the glimmers are flurries. Using mittens, boots, a scarf, and an umbrella, Madeleine turns herself into a warm, dry house.

7:10 A.M.

In the back bedroom of the Kelly family’s row home, Clare Kelly plaits her second, perfect braid. She administers advice to her little sister who sits on the bed, transfixed. Clare is proud of herself for allowing Elissa to pal around. She can learn from Clare’s mistakes—not that there have been many—and her achievements—which have been plentiful, praise God. Student of the Week, Month, and Year certificates pose on her wall.

Clare finishes the braid with a pink barrette and admires herself. The barrettes will reflect the light of Saint Anthony’s stained glass when Father Gary announces, “Clare Kelly will now lead us in the responsorial song.” She will step-touch to the foot of the altar under the worshipful gazes of her classmates. Step-touch to genuflect at the statue of Mary, making full stops on her forehead, breastplate, left collarbone, right collarbone. Step-touch to the microphone.

Clare Kelly never has shark fins when she combs her hair into a ponytail, and her braids always part diplomatically.

Her mother gazes at her daughters from the doorway. “Time to go to school.”

Clare is proud of herself for being the kind of daughter who doesn’t rebel against her parents. Even when they told her she was having a little sister after they’d promised she’d be an only child. She could have answered “garbage” when they pointed to her mother’s swollen belly and asked what she thought was in there. But did she say garbage, or a stocking of poop or a lizard? No. Clare Kelly said, “My li’l sister,” taking care to furbish “little” with an adorable slur.

Clare helps Elissa into her backpack before donning her own. The Kelly girls file down the carpeted stairs, past the makeshift bar with a sign that reads Kelly’s Pub, to where their father waits, cheek thrust out in anticipation of each girl’s kiss. Every day this kiss, then the short city walk to school. Clare, then Elissa plants one on Dad’s smooth cheek and Mom opens the door. Flurries fall in the halo of streetlights. Clare elbows Elissa out of the way. She wants to be first into this snow-wonderful world.

It is her last conscious thought before being struck by a speeding bicyclist.

Clare is hurled against the brightening sky by the force of the handlebars against her thigh. The rider, sliding on his side, meets her falling figure against the base of an electric pole. As if they planned.

Elissa’s screaming hits enviable notes. What range that little girl has!

7:15 A.M.

Café Santiago comprises the bottom level of a two-story, aggressively flower-boxed building on Ninth Street. The store fits a table with eight chairs and three display cases selling sweets and prepared foods that vary daily depending on Mrs. Santiago’s moods. Christmas cacti bloom in empty gravy cans on the windowsills. Above the counter hangs a life-sized portrait of Mrs. Santiago’s late husband, Daniel. Mrs. Santiago lives on the second floor with her dog, Pedro, who is currently, on Christmas Eve Eve, missing.

She stands behind the counter feeding sausage mixture into a casing machine, coaxing out smooth links from the other side. The shop smells like fennel, the cold, and coffee.

Sarina Greene, fifth-grade art teacher at Saint Anthony of the Immaculate Heart, peers into a display case, weighing the merits of three different kinds of caramel. She sways to the instrumental jazz playing on the café’s speakers and points to a pile of stately cubes. “Would you say this caramel is sweet or more chalky?”

“Sweet,” says Mrs. Santiago.

“That would be good for Brianna but not for the other Brianna,” Sarina says.

“How many do you need?”

“Only one, I suppose, but it’s a popular name. We call one Brie to keep them straight.”

“How many,” Mrs. Santiago says, “kinds of caramel?”

Sarina grimaces. “My brain’s not working today. I looked for my keys for ten minutes. They were in my hand.”

“Must be love.”

“Ha!” Sarina cries. Mrs. Santiago’s elbow startles a stack of coffee filters. She stoops to collect them. “I don’t know how many kinds I need,” Sarina says. “I have twenty-four students. Leigh is allergic to everything and Duke is diabetic. He’d turn red if he ate a caramel apple. Become unresponsive and die.”

Mrs. Santiago blinks. “We don’t want that.”

“Which caramel would you use?”

“Medium dark.”

“Fine.” Sarina nods. It is her first year back in her hometown since high school, summoned by her mother’s death and the aching blank page that follows divorce. She counteracts the feeling of being a failure by plunging into every task like a happy doe into brush. Today: these caramels. Last night: spelling each of her student’s names in glitter on the brims of twenty-four Santa hats.

“One pound?” Mrs. Santiago says. “A pound and a half?”

Sarina’s phone begins its embarrassing call at the bottom of her purse: “Wonderwall.” She roots through her bag, finds what she thinks is her phone, and shows it to herself—calculator. She paws through tissues, a sewing kit, her wallet, pipe cleaners, a parking voucher from a crochet

class she tried, where she made a tote bag, this tote bag, out of old T-shirts—it is kicky but contains too many caverns. The song continues its assault, then—at last—her phone.

Her grade partner is calling, a woman who finds no situation over which she can’t become frantic. Sarina dumps the call into voice mail. The bells of the door clatter. Georgina McGlynn enters from the dark, shaking snowflakes from her coat. Sarina and Georgina, who everyone calls Georgie, went to high school together.

“Picking up a pie for tonight,” Georgie says with an apologetic air. As if she needs a reason to be in this shop at this hour. This cues Mrs. Santiago, who disappears into the back.

“Pie is …” Sarina says.

The women look in different directions. No radio plays. The street hovers between night and dawn. This is the second time they’ve run into each other in the neighborhood, both times marked by stammering and adamant friendliness.

“Key lime,” says Georgie.

“Wonderful.”

“You should come!” Georgie’s volume frightens both of them. “It’s the old gang.”

Sarina has never been part of a gang. “Tonight?” she says, then remembers Georgie has already said tonight. A forgotten flurry announces itself on the top of her head. It burns wet. “I can’t tonight.”

“You must.” Georgie’s tone is panicked. “They would love to see you. Michael, Ben …”

Mrs. Santiago returns with the pie.

“You don’t want this bag of potatoes hanging around,” Sarina says.

The room’s silence doubles down. Sarina has no idea why, in the presence of this ex–punk queen from high school, she is compelled to insult herself. Bundling the pie, Mrs. Santiago tsks.

“You’re not a bag of potatoes,” Georgie says. “Is that ‘Wonderwall’?”

Sarina searches the bag again. This time it’s Marcos, her ex-husband. “Must be Call Sarina Day,” she jokes, dumping the call into voice mail. Georgie wasn’t present for the other phone call, she realizes. So the joke makes no sense and Sarina now seems like a girl who rejoices upon receiving any communication from the outside world.