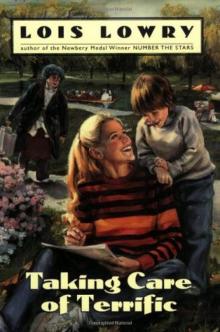

Taking Care of Terrific

Lois Lowry

Taking Care Of Terrific

Lois Lowry

* * *

Houghton Mifflin Company Boston

* * *

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Lowry, Lois.

Taking care of Terrific.

Summary: Taking her overprotected young charge to

the public park to broaden his horizons, fourteen-year-

old baby sitter Enid enjoys unexpected friendships with

a black saxophonist and a bag lady until she is charged

with kidnapping.

[1. Baby sitters—Fiction. 2. Parks—Fiction.

3. Boston (Mass.)—Fiction] I. Title.

PZ7.L9673Tak 1983 [Fic] 82-23331

ISBN 0-395-34070-5

Copyright © 1983 by Lois Lowry

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by

any information storage or retrieval system, except as

may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in

writing from the publisher. For information about permission

to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue

South, New York, New York 10003.

Printed in the United States of America

HAD 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12

* * *

For Erik and Richard

* * *

Keep a green tree in your heart and perhaps the singing bird will come.

— Chinese proverb

Chapter 1

I threw down the book I'd been trying to read, stared out of my bedroom window for a while at the tops of the trees, sighed, and picked up my sketch pad. I doodled a few designs: leaves and stems curling around each other, intertwined. Carefully I colored in the leaves with a green marking pen, leaving some white spots for highlights, so that they looked glossy and radiant.

Maybe, I thought glumly, I'd feel better if someone sprinkled me with fertilizer. Plants do.

Once I bought a dumb little jade plant at a street fair. It really needed somebody; it looked crummy and neglected, like an orphan who's never been taken to the zoo. I gave it to my mother on her birthday, and she took over with her little tweezers and tweakers and her bottles of plant food, talking to it: "There, now. This will make you perk up," and eureka, it perked up. Grew. Flourished.

Probably my mother talked like that to me when I was little. She hasn't for a long time, though. My parents chose the Carstairs School because in the catalogue it said, "We encourage independence." (It also said, "We charge fifty-two hundred dollars a year tuition for day students, plus lab fees and books, and our graduates get into the best Ivy League college"; but the thing that hooked my parents was the "We encourage independence.")

Murmuring "There now, this will perk you up" to a fourteen-year-old girl probably does not encourage independence. So that is why my mother says that only to small droopy plants suffering from aphids or root rot. To me, when I look, feel, and am droopy, discouraged, depressed, and practically about to throw myself out of my bedroom window because nothing in my life seems to go the way I want it to, my mother says, "Enid, for heaven's sake, you have to learn to solve your own problems. And it might be a start if you would do something about your hair."

Sometimes I wish I were a philodendron.

If I were a philodendron, I would not be sitting here, a prisoner in my own bedroom, thinking about what happened this summer, scared stiff and super miserable.

It was the best summer of my life. I found some new friends. They were friends who needed me. They were wilted. I tried to encourage them to bloom, just the way my mother coaxes her begonias into blossoming. And it worked. I saw it work. We put the whole thing together so that on one night—just last week, a night I'll never forget no matter what happens, and even if I never see most of those friends again—on that night we were all together, and a thin slice of moon was shining; there was music playing, and the green was all around us so green that you could feel it down inside your soul, and everybody's life was changed. At least for an hour. Maybe that is all you ever get in this world, one hour like that.

Then, of course, came the horrible rest of it: police, some on shiny-hooved horses, others in cars with blue lights flashing; newspaper people yelling questions that had no answers; a TV guy with a camera balanced on his shoulder. Bright lights and bright lights and bright lights; handcuffs and shoving and a loudspeaker. Finally, in the police station, my parents. My mother actually had no make-up on; they'd gotten her out of bed. Very few people have ever seen my mother with no make-up. And until that night, I doubt if anyone had ever seen my mother cry.

And now I've been in my bedroom for a week: my bedroom with the yellow bedspread that I once thought made me feel cheerful all the time. It doesn't anymore.

Downstairs, people have been coming and going for a week. Conferences have been held in my father's study. My father is a lawyer, and he is representing me even though he hasn't handled a criminal case in years. From my window I can see the taxis and the cars come, and I can see the people come up the front steps of our house. Policemen in uniform. Lawyers, one of them a man with a face like a frozen leather glove. Wilma Sandroff, the world-famous child psychologist, hotshot expert on getting in touch with your feelings, which is a lot of crap because Wilma Sandroff hasn't been in touch with her own feelings in about forty-nine years, and I happen to know that her own three children hate her guts. And that one of them, her oldest, is at this very moment sitting in his own bedroom three blocks away.

Well, I don't want to think about him now.

They are all downstairs negotiating. What they are negotiating is what is going to happen to me.

If I have to go to jail, I wonder if they will let me keep a little green plant in my cell.

Chapter 2

Just to put things into the right perspective: I changed my name first. Before the kidnapping—and all the other crimes they're accusing me of.

So it was not that I was using an alias, the way the newspapers said.

It was this way. I have always hated my name: Enid Irene Crowley. Now really. It would be a terrible name even for an old woman; for a fourteen-year-old girl it was unbearable.

Maybe you have never noticed, but the most hideous adjectives end in the letter d. Pick up any one of Stephen King's horror novels and open to any page; you'll find them: horrid, putrid, sordid, acrid, viscid, squalid. And the very worst: fetid. Probably you don't even know what "fetid" means; it isn't a word you hear people use very often. But if you read a lot, the way I do, especially horror books, you come across that word, usually describing the breath of creatures who have returned from the grave and are covered with green slime. They all have fetid breath.

Enid isn't a repulsive adjective, as far as I know. But it sounds as if it should be. I find myself making up sentences with the word "enid" in them. Like: "She had been trapped in the crypt for seventeen days; her fingernails had begun to rot, she was suffering from gangrene of the toes, and her once-lustrous blond hair had become limp and enid, with moss growing in it."

You can see why I decided to change my name.

Of course I didn't do it legally. Since my father is a lawyer, I suppose he would know how. But I couldn't ask my father to do that. It was his great-aunt whom I was named for: the very rich one. I think they hoped that she would leave her money to me. She didn't, of course. She left it all to a residential home for seafaring men; no one could figure out why, and they tried to contest the will. But apparently she was of very

sound mind when she wrote it, and all the money went to the seafaring men, whoever they are. I hope they bought a whole assortment of video games and that they have seafood dinners sent in from Pier 4 every night.

I figure my great- aunt Enid probably had a love affair with a sea captain once. Good for her. During the whole time I knew her, she lived all alone in a house on Beacon Hill, with velvet draperies pulled tightly closed so that it was always dark. She read all the novels of Henry James, one after another; and when she finished the last one, she began at the beginning again. She died with The Portrait of a Lady open in her hands at [>].

I sure hope she had a love affair with a sea captain once. If all you ever get out of life is the novels of Henry James, it hardly seems worthwhile putting in your eighty-three years.

I myself have always intended to get a great deal more than that out of life. But I thought that with a name like Enid, my chances weren't too good.

So—informally—I began to call myself Cynthia as soon as school ended in June. When I made an appointment to have my hair trimmed at Antone's on Newbury Street, I made the appointment in the name of Cynthia Crowley. When I was stopped by a man on Berkeley Street one day and asked to sign a petition denouncing transvestites, I signed the petition as Cynthia Crowley, even though I wasn't exactly sure what transvestites were. And when I enrolled in the morning art classes at the Museum of Fine Arts, I enrolled as Cynthia Crowley. I decided that I would spend the summer meeting new people and maybe becoming something of a new person myself.

I decided that my new life was going to have elements of romance, intrigue, danger, and pathos in it. I thought of it as a menu from which I could order two from Column A and one from Column B.

I was supposed to spend my spare time making sketches for my art class. I decided to do that in my very favorite green place, the Public Garden, which is just two blocks from my house. I decided that in the Public Garden, where I would be Cynthia, I could also find romance, intrigue, danger, and pathos.

If that sounds foolish to you, it only means that you don't know Boston.

Chapter 3

My mother is a radiologist. She can do stuff like aim a billion volts of lethal rays at a microscopic mole on somebody's big toe. So you would think she'd be very perceptive, right? You'd think she'd be able to see what's going on around her all the time, right?

Wrong.

She hires people to keep track of things. At work, she hires people who tell her what patients she has to see that day, what meetings she has to go to, maybe even what day of the week it is.

At home, she has Mrs. Kolodny. My mother hired Mrs. Kolodny years ago—fourteen, to be exact—when I was born. Mrs. Kolodny lives in our house, and she is supposed to keep track of things here; she is supposed to keep track of me. Most of the time it is the other way around. Mrs. Kolodny is one of the flakiest people I have ever met. In fourteen years, my mother has never noticed this.

Mrs. Kolodny watches soap operas from one to three every afternoon, sitting on a plastic drop-cloth that she puts over a chair in the study so that she won't wrinkle the chair.

In the morning she watches the Donahue show. Sometimes she tells me, with great satisfaction, "Donahue had more of those preverts on today. People called in from all over and condemned them."

"Preverts," to Mrs. Kolodny, means gay people, divorced people, people with open marriages, people who belong to any religion she hasn't heard of, and one time a woman who had a pet ocelot. She really hates it when Donahue has a politician or an environmentalist on his show.

When she's not watching TV, Mrs. Kolodny reads. Mostly she reads gothic romances. The heroines are always named things like Serena or Valerie, and they are always seduced by sinister men whom they encounter on cliffs during thunderstorms. It always surprises Mrs. Kolodny when they are seduced.

"Listen to this, Enid," she said to me one morning, moving her finger under a line of print in a book. "'We mustn't, Jonathan,' whispered Catherina as he began roughly to remove her rain-spattered gown. 'Please, Jonathan. I am promised to Lord Farquhar! We mustn't!'"

"Yeah," I said.

"She meant it, too," said Mrs. Kolodny. "She'd been promised to that lord since she was twelve!"

"Yeah," I said.

"And then on the very next page," Mrs. Kolodny said angrily, "she forgot all her very principles. How can someone forget all her principles in one page?"

"Beats me," I said.

Mrs. Kolodny sighed, marked her place in the book, and went off to run the vacuum cleaner for a few minutes.

When she isn't watching TV or reading, Mrs. Kolodny cleans. She does all her cleaning during commercials or between chapters.

After a war approximately the size of World War II, she stopped cleaning my bedroom. I started that war myself, after Mrs. Kolodny had vacuumed up an entire science experiment that was laid out on my desk. She said it was rotten bananas and cookie crumbs. I said it was genetic research on fruit flies.

Mom tried to remain neutral because she did sort of like the idea of my doing scientific research, although she sympathized with Mrs. Kolodny on hygienic grounds.

Dad tried to stay out of it altogether, but Mrs. Kolodny told him that the vacuum cleaner needed eighty-five dollars' worth of repairs because the rotten banana had fouled up its insides. Then Dad said that was it, that was absolutely it, and she was not to clean my room anymore, ever.

My room is on the top floor of our house on Marlborough Street. The fifth. And Mrs. Kolodny has what my mom says is phlebitis, but Mrs. Kolodny calls it housemaid's knee, and she always hated going up to the fifth floor.

We get along okay now that she doesn't clean my room anymore. Sometimes I give her backrubs. And we talk about books. There's not much to say about gothic romances, but every now and then she surprises me and reads something intellectual, like Moby Dick. She got fascinated with Moby Dick, which she borrowed from me when I had to read it for school, and for a long time we talked about whaling and how neat it would be to go out on a whaling ship. I think, though, that she envisioned it stopping in the Virgin Islands now and then, like a cruise ship, and thought she could do lots of duty-free shopping. It seemed like a good way of life to her, harpooning whales for a few days, melting down blubber, and then sipping a piña colada and taking a swim at St. Croix. There would be no preverts around. I think she had the idea that Gregory Peck would be along.

The problem with most people's lives is that they have lost the capacity to believe that Gregory Peck would be along.

"Enid," said Mrs. Kolodny one morning as I came in from my art class, "some woman called. She wants you to babysit."

"Okay. Who was it? When does she want me?"

Mrs. Kolodny's face froze into her glazed expression. One of the things I know about Mrs. Kolodny, that my mother doesn't know, is that she can't remember things. Certain things fall out of her brain like water falling through a sieve. When that happens, she gets this expression on her face; her eyes glaze as if someone has frosted her onto the top of a cake and she will be like that, staring into space, forever. I know how to deal with it, though.

"Think back," I said. "The phone rang. It was a woman, and she asked for me, and I wasn't home. What did she say?"

The glazed frosting began to melt on her face, and she thought. "She said she knew your mother from the Civil Club."

"There isn't any Civil Club, Mrs. Kolodny. My mother belongs to the Civic Association and the Civil Liberties Union. It must have been one of those."

The glazed look again. She was drawing a blank.

"Well," I told her, "that part doesn't matter. Think back. Can you remember her name?"

She thought some more. "I wrote it down," she said finally.

"Which phone?"

She brightened. "Kitchen. I was starting to do the laundry and reading Passion at Penzance. I answered the phone in the kitchen."

The washing machine was thumping away in the kitchen. The paperback copy of Passion at Penzance h

ad a coupon for twenty-five cents off a pound of Maxwell House coffee stuck in it as a bookmark and was lying on the table. Standing on top of the dryer, next to the washing machine, was a large box of instant mashed potatoes. I had a horrible feeling about that, but I let it pass for a moment. On the pad of paper by the phone was written, in Mrs. Kolodny's tiny, scrunched handwriting: "Mz Cameron, babysit." Under that was a telephone number.

"Mrs. Kolodny," I said, before I dialed Ms. Cameron's number, "why are the instant mashed potatoes on top of the dryer?"

She looked. "Omigod," she said.

"You didn't."

"Omigod. I had them out to thicken the chowder. And the box is the same size—"

"As the detergent box, right?"

"Omigod."

"You want to look or shall I?"

She just groaned. I looked. It wasn't too bad. Lumpy, but not disastrous. I found the box of Tide, put the instant potatoes back in the cupboard, and told Mrs. Kolodny, "Just let it run. Then do the clothes again with the Tide. It's not the end of the world." I rubbed her back for a minute because she looked so humiliated, and a backrub is always good for humiliation.

Ms. Cameron answered the phone on the second ring, and I could picture her from her voice. Young. Tall. Cheekbones. The sort of voice that has gone to all the best schools and knows which syllables to pronounce which way. She was the kind of person who would wear only unobtrusive make-up, who would eat yogurt, listen to chamber music, ride a bike, jog, and save whales. But her bike would be a four-hundred-dollar Peugeot, and she would have the yogurt delivered from DeLuca's, along with cases of the right wine. She would go to antinuclear demonstrations wearing designer jeans and monogrammed sweaters from Land's End.

Funny how you can tell all of that from a voice.

She would no doubt have a rosy-cheeked baby with a biblical name, brought up on breast milk and natural foods. She would have read books about parenting. The baby would ride around in an expensive carrier on her back.