Daddy's Girl

L. T. Meade

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, D Alexander and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

DADDY'S GIRL

BY L. T. MEADE

Author of "A Very Naughty Girl," "Polly, A New Fashioned Girl," "Palace Beautiful," "Sweet Girl Graduate," "World of Girls," etc., etc.

"Suffer the little children to come unto me."

A. L. BURT COMPANY, PUBLISHERS 52-58 DUANE STREET, NEW YORK.

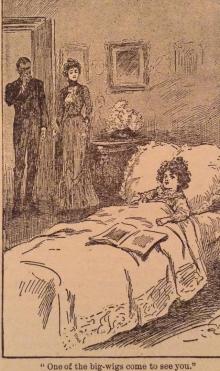

DADDY'S GIRL. _Frontispiece._]

DADDY'S GIRL.

CHAPTER I.

Philip Ogilvie and his pretty wife were quarrelling, as their customwas, in the drawing-room of the great house in Belgrave Square, butthe Angel in the nursery upstairs knew nothing at all about that. Shewas eight years old, and was, at that critical moment when her fatherand mother were having words which might embitter all their lives, andperhaps sever them for ever, unconsciously and happily decoratingherself before the nursery looking-glass.

The occasion was an important one, and the Angel's rosebud lips werepursed up in her anxiety, and her dark, pretty brows were somewhatraised, and her very blue eyes were fixed on her own charming littlereflection.

"Shall it be buttercups, or daisies, or both?" thought the Angel toherself.

A box of wild flowers, which had come up from the country that day,lay handy. There were violets and primroses, and quantities ofbuttercups and daisies, amongst these treasures.

"Mother likes me when I am pretty, father likes me anyhow," shethought, and then she stood and contemplated herself, and pensivelytook up a bunch of daisies and held them against her small, slightlyflushed cheek, and then tried the effect of the buttercups in hergolden brown hair. By-and-by, she skipped away from the looking-glass,and ran up to a tall, somewhat austere lady, who was seated at a roundtable, writing busily.

"What do you want, Sibyl? Don't disturb me now," said this individual.

"It is only just for a moment," replied the Angel, knitting her brows,and standing in such a position that she excluded all light fromfalling on the severe-looking lady's writing-pad.

"Which is the prettiest, buttercups or daisies, or the two twisted uptogether?" she said.

"Oh, don't worry me, child, I want to catch this post. My brother isvery ill, and he'll be so annoyed if he doesn't hear from me. Did yousay buttercups and daisies mixed? Yes, of course, mix them, that isthe old nursery rhyme."

The little Sibyl stamped a small foot encased in a red shoe with animpatient movement, and turned once more to contemplate herself inthe glass. Miss Winstead, the governess, resumed her letter, and aclock on the mantelpiece struck out seven silvery chimes.

"They'll be going in to dinner; I must be very quick indeed," thoughtthe child. She began to pull out the flowers, to arrange them inlittle groups, and presently, by the aid of numerous pins, to deck hersmall person.

"Mother likes me when I am pretty," she repeated softly under herbreath, "but father likes me anyhow." She thought over this somewhatcurious problem. Why should father like her anyhow? Why should motheronly kiss her and pet her when she was downright pretty?

"Do I look pretty?" she said at last, dancing back to the governess'sside.

Miss Winstead dropped her pen and looked up at the radiant littlefigure. She had contrived to tie some of the wild flowers together,and had encircled them round her white forehead, and mixed them in herflowing locks, and here, there, and everywhere on her white dress werebunches of buttercups and daisies, with a few violets thrown in.

"Do I look pretty?" repeated Sibyl Ogilvie.

"You are a very vain little girl," said Miss Winstead. "I won't tellyou whether you look pretty or not, you ought not to think of yourlooks. God does not like people who think whether they are pretty ornot. He likes humble-minded little girls. Now don't interrupt me anymore."

"There's the gong, I'm off," cried Sibyl. She kissed her hand to MissWinstead, her face all alight with happiness.

"I know I am pretty, she always talks like that when I am," thoughtthe child, who had a very keen insight into character. "Mother willkiss me to-night, I am so glad. I wonder if Jesus Christ thinks mepretty, too."

Sibyl Ogilvie, aged eight, had a theology of her own. It was extremelysimple, and had no perplexing elements about it. There were threepersons who were absolutely perfect. Jesus Christ Who lived in heaven,but Who saw everything that took place on earth, and her own fatherand mother. No one else was absolutely without sin, but these threewere. It was a most comfortable doctrine, and it sustained her littleheart through some perplexing passages in her small life. She used toshut her eyes when her mother frowned, and say softly under herbreath--

"It's not wrong, 'cos it's mother. Mother couldn't do nothing wrong,no more than Jesus could"; and she used to stop her ears when hermother's voice, sharp and passionate, rang across the room. Somethingwas trying mother dreadfully, but mother had a right to be angry; shewas not sinful, like nurse, when she got into her tantrums. As tofather, he was never cross. He did look tired and disturbed sometimes.It must be because he was sorry for the rest of the world. Yes, fatherand mother were perfection. It was a great support to know this. Itwas a very great honor to have been born their little girl. Everymorning when Sibyl knelt to pray, and every evening when she offeredup her nightly petitions, she thanked God most earnestly for havinggiven her as parents those two perfect people known to the world asPhilip Ogilvie and his wife.

"It was so awfully kind of you, Jesus," Sibyl would say, "and I musttry to grow up as nearly good as I can, because of You and father andmother. I must try not to be cross, and I must try not to be vain, andI must try to love my lessons. I don't think I am really vain, Jesus.It is just because my mother likes me best when I am pretty that Iwant to be pretty. It's for no other reason, really and truly; but Idon't like lessons, particularly spelling lessons. I cannot pretend Ido. Can I?"

Jesus never made any audible response to the child's query, but sheoften felt a little tug at her heart which caused her to fly to herspelling-book and learn one or two difficult words with frantic zeal.

As she ran downstairs now, she reflected over the problem of hermother's kisses being softest and her mother's eyes kindest when herown eyes were bright and her little figure radiant; and she alsothought of the other problem, of her grave-eyed father always lovingher, no matter whether her frock was torn, her hair untidy, or herlittle face smudged.

Because of her cherubic face, Sibyl had been called the Angel whenquite a baby, and somehow the name stuck to her, particularly on thelips of her father. It is true she had a sparkling face and softfeatures and blue eyes; but she was, when all is said and done, asomewhat worldly little angel, and had, both in the opinions of MissWinstead and nurse, as many faults as could well be packed into thebreast of one small child. Both admitted that Sibyl had a very lovingheart, but she was fearless, headstrong, at times even defiant, andwas very naughty and idle over her lessons.

Miss Winstead was fond of taking complaints of Sibyl to Mrs. Ogilvie,and she was fond, also, of hoping against hope that these complaintswould lead to satisfactory results; but, as a matter of fact, Mrs.Ogilvie never troubled herself about them. She was the sort of womanwho took the lives of others with absolute unconcern; her own lifeabsorbed every thought and every feeling. Anything that added to herown comfort was esteemed; anything that worried her was shut as muchas possible out of sight. She was fond of Sibyl in her careless way.There were moments when she was proud of the pretty and attractivechild, but she had not the slightest idea of attempting to mould hercharacter, nor of becoming her instructress. One of Mrs. Ogilvie'sfavorite theories was that mothers should not educate their children.

"The child should go to the mother for love and petting," she wouldsay. "Miss Winstead may complain of the darl

ing as much as shepleases, but need not suppose that I shall scold her."

It was Sibyl's father, after all, who now and then spoke to her abouther unworthy conduct.

"You are called the Angel, and you must try to act up to your name,"he said on one of these occasions, fixing his own dark-grey eyes onthe little girl.

"Oh, yes, father," answered the Angel, "but, you see, I wasn't bornthat way, same as you was. It seems a pity, doesn't it? You're perfectand I am not. I can't help the way I was born, can I, father?"

"No; no one is perfect, darling," replied the father.

"You are," answered the Angel, and she gave her head a defiant toss."You and my mother and my beautiful Lord Jesus up in heaven. But I'lltry to please you, father, so don't knit up your forehead."

Sibyl as she spoke laid her soft hand on her father's brow and triedto smooth out some wrinkles.

"Same as if you was an old man," she said: "but you're perfect,perfect, and I love you, I love you," and she encircled his neck withher soft arms and pressed many kisses on his face.

On these occasions Philip Ogilvie felt uncomfortable, for he was a manwith many passions and beset with infirmities, and at the time whenSibyl praised him most, when she uttered her charming, confidentwords, and raised her eyes full of absolute faith to his, he wasthinking with a strange acute pain at his heart of a transaction whichhe might undertake and of a temptation which he knew well was soon tobe presented to him.

"I should not like the child to know about it," was his reflection;"but all the same, if I do it, if I fall, it will be for her sake, forhers alone."