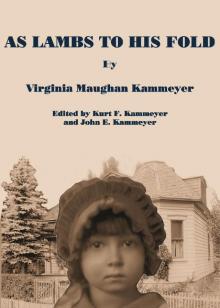

As Lambs to His Fold

Kurt F. Kammeyer

AS LAMBS TO HIS FOLD

By

Virginia Maughan Kammeyer

Edited by Kurt F. Kammeyer and John E. Kammeyer

Copyright 2012 Kurt F. Kammeyer

License Notes

AS LAMBS TO HIS FOLD

CENTRAL UTAH, THE SUMMER OF 1938:

Nine-year-old cousins Bethany Markham and Leatrice Latimer are inspired to want to get to heaven. It should be easy for girls as righteous as them…

Meet the girls and their extended families and relations, including Doctor/Bishop Lindblum, Great-Aunt Salina May Roundtree Gillis, 98-year-old Brother Nickelbee, glamorous Aunt Francie, a pot of African Violets, and Mooey-Moocher the cow.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Virginia Maughan Kammeyer was born in Cedar City, Utah, in 1925, the second of five children. Her father was, at various times, a high school principal, college president, rancher, professor of agriculture, stake president and mission president. Her mother was a school teacher, and noted writer, poet and wit. Jinny graduated from BYU in 1946, and taught school for two years before marrying Fred T. Kammeyer in 1948. They had six children. She died in Bellevue, Washington, in August 1999.

She won many awards for her poetry, which was collected and published in The Joy Book, in 2001. The three novels in this series were among her last projects before she died.

FORWARD

This book was one of our mother’s last projects before she died. She worked on it off and on over several years, and it was in almost finished form when she died.

As Lambs to His Fold is a deceptively simple-sounding tale, and conceals how much craftsmanship went into her settings and characters. She wrote:

“Do not be led astray by what you read, by the cheap and shoddy. “Cheap” doesn’t necessarily mean “immoral,” but rather that which is worth little. We can recognize the cheap and shoddy in religion — the pulpit thumpers, those who play upon people’s emotions. There are some traps in literature: those which appeal to the emotions you already have, and leave you just the same as before. Lazy writers will “use” readers this way; and the unthinking reader will not see it as a trap, but will say, “Oh, wasn’t that wonderful” — because it says exactly what he was thinking.

“There is too much of this in Mormon literature; the book with the predictable characters and the predictable ending, which pounds home a predictable moral. Because all our talks and all the lessons we teach in church are based on pointing out a moral and promoting faith, we think this is all we need in our literature. There is nothing wrong with this, if the characters are allowed to work out their problems themselves. Greek writers scorned the “chariot of the gods coming down to rescue people.” A careless Mormon writer will get his characters in a fix and then leave it to God to rescue them — by a miracle, or a revelation, or a visit from the Three Nephites. This is not only bad writing, it is false doctrine. We all know that miracles happen, but only after we have done everything we can to solve the situation.”

Good fiction tends to take on a life of its own during the writing, and heads off in directions even the author didn’t anticipate. Bad fiction tends to be contrived, heading where the author intends, with the characters led around like puppets. My mother was scornful of “historical fiction” featuring actions impossible to the time or context of the story, or physically impossible. She wrote, addressing hack novelists:

WESTERN DAZE

Moving as rapidly as light

You type a novel in a night,

Then galloping at frantic pace

Over the hills your heroes race.

From cattle ranch, to gambling room,

To mesa bluff and back they zoom.

How can you, writing at such rate,

Keep places, plots, and people straight?

Your marshal, now — I fear that he

May someday meet catastrophe,

(A mix-up by some typing elf)

And handcuff, jail, then hang — himself.

Good historical fiction is difficult to write, and it’s easy for little things to go wrong when meshing the real with the imagined, even for a period as recent as sixty years ago. I don’t know if Mom ever read J.R.R. Tolkien’s classic essay “On Fairy Stories.” If she didn’t, then she was familiar with his theories from other sources. Tolkien held that if a writer is to win a readers’ “temporary suspension of disbelief” in the imagined setting, then the story must have perfect internal consistency, however normally implausible the setting. (One thinks of Chris Heimerdingers’ beguiling “Tennis Shoes Among the Nephites” series.) My mother was of Tolkien’s opinion, and tended to do meticulous background research — she left an unfinished novel set in Manhattan in the 1880’s, and her research included maps showing the location of prominent landmarks, and pictures of what these looked like. She had an ear for voices — go through this book, for example, and count how many Western American dialects she employs.

To maintain consistency, she created detailed backgrounds for her major characters, regardless of whether the reader was aware of this. This biographical material became the third book in this series, A Bright Particular Star. She was aware of the unpredictability of real life, and attempted to simulate this in her writing. There is plenty of pathos and sentimentality in my mother’s novels, but it is invariably mixed with sorrow and loss.

John Kammeyer

Sammamish, Washington

February 2002