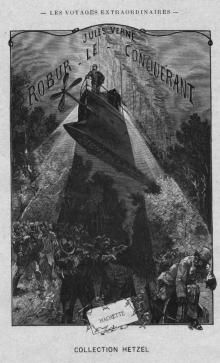

Robur-le-conquerant. English

Jules Verne

Produced by Norman Wolcott.

ROBUR THE CONQUEROR

By

Jules Verne

Contents

I Mysterious sounds II Agreement Impossible III A Visitor is Announced IV In Which a New Character Appears V Another Disappearance VI The President and Secretary Suspend Hostilities VII On board the Albatross VIII The Balloonists Refuse to be Convinced IX Across the Prairie X Westward--but Whither? XI The Wide Pacific XII Through the Himalayas XIII Over the Caspian XIV The Aeronef at Full Speed XV A Skirmish in Dahomey XVI Over the Atlantic XVII The Shipwrecked Crew XVIII Over the Volcano XIX Anchored at Last XX The Wreck of the Albatross XXI The Institute Again XXII The Go-Ahead is Launched XXIII The Grand Collapse

Chapter I

MYSTERIOUS SOUNDS

BANG! Bang!

The pistol shots were almost simultaneous. A cow peacefully grazingfifty yards away received one of the bullets in her back. She hadnothing to do with the quarrel all the same.

Neither of the adversaries was hit.

Who were these two gentlemen? We do not know, although this would bean excellent opportunity to hand down their names to posterity. Allwe can say is that the elder was an Englishman and the younger anAmerican, and both of them were old enough to know better.

So far as recording in what locality the inoffensive ruminant hadjust tasted her last tuft of herbage, nothing can be easier. It wason the left bank of Niagara, not far from the suspension bridge whichjoins the American to the Canadian bank three miles from the falls.

The Englishman stepped up to the American.

"I contend, nevertheless, that it was 'Rule Britannia!'"

"And I say it was 'Yankee Doodle!'" replied the young American.

The dispute was about to begin again when one of theseconds--doubtless in the interests of the milk trade--interposed.

"Suppose we say it was 'Rule Doodle' and 'Yankee Britannia' andadjourn to breakfast?"

This compromise between the national airs of Great Britain and theUnited States was adopted to the general satisfaction. The Americansand Englishmen walked up the left bank of the Niagara on their way toGoat Island, the neutral ground between the falls. Let us leave themin the presence of the boiled eggs and traditional ham, and floodsenough of tea to make the cataract jealous, and trouble ourselves nomore about them. It is extremely unlikely that we shall again meetwith them in this story.

Which was right; the Englishman or the American? It is not easy tosay. Anyhow the duel shows how great was the excitement, not only inthe new but also in the old world, with regard to an inexplicablephenomenon which for a month or more had driven everybody todistraction.

Never had the sky been so much looked at since the appearance of manon the terrestrial globe. The night before an aerial trumpet hadblared its brazen notes through space immediately over that part ofCanada between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. Some people had heardthose notes as "Yankee Doodle," others had heard them as "RuleBritannia," and hence the quarrel between the Anglo-Saxons, whichended with the breakfast on Goat Island. Perhaps it was neither onenor the other of these patriotic tunes, but what was undoubted by allwas that these extraordinary sounds had seemed to descend from thesky to the earth.

What could it be? Was it some exuberant aeronaut rejoicing on thatsonorous instrument of which the Renommee makes such obstreperous use?

No! There was no balloon and there were no aeronauts. Some strangephenomenon had occurred in the higher zones of the atmosphere, aphenomenon of which neither the nature nor the cause could beexplained. Today it appeared over America; forty-eight hoursafterwards it was over Europe; a week later it was in Asia over theCelestial Empire.

Hence in every country of the world--empire, kingdom, or republic--therewas anxiety which it was important to allay. If you hear inyour house strange and inexplicable noises, do you not at onceendeavor to discover the cause? And if your search is in vain, do younot leave your house and take up your quarters in another? But inthis case the house was the terrestrial globe! There are no means ofleaving that house for the moon or Mars, or Venus, or Jupiter, orany other planet of the solar system. And so of necessity we have tofind out what it is that takes place, not in the infinite void, butwithin the atmospherical zones. In fact, if there is no air there isno noise, and as there was a noise--that famous trumpet, to wit--thephenomenon must occur in the air, the density of which invariablydiminishes, and which does not extend for more than six miles roundour spheroid.

Naturally the newspapers took up the question in their thousands, andtreated it in every form, throwing on it both light and darkness,recording many things about it true or false, alarming andtranquillizing their readers--as the sale required--and almostdriving ordinary people mad. At one blow party politics droppedunheeded--and the affairs of the world went on none the worse for it.

But what could this thing be? There was not an observatory that wasnot applied to. If an observatory could not give a satisfactoryanswer what was the use of observatories? If astronomers, who doubledand tripled the stars a hundred thousand million miles away, couldnot explain a phenomenon occurring only a few miles off, what was theuse of astronomers?

The observatory at Paris was very guarded in what it said. In themathematical section they had not thought the statement worthnoticing; in the meridional section they knew nothing about it; inthe physical observatory they had not come across it; in the geodeticsection they had had no observation; in the meteorological sectionthere had been no record; in the calculating room they had hadnothing to deal with. At any rate this confession was a frank one,and the same frankness characterized the replies from the observatoryof Montsouris and the magnetic station in the park of St. Maur. Thesame respect for the truth distinguished the Bureau des Longitudes.

The provinces were slightly more affirmative. Perhaps in the night ofthe fifth and the morning of the sixth of May there had appeared aflash of light of electrical origin which lasted about twentyseconds. At the Pic du Midi this light appeared between nine and tenin the evening. At the Meteorological Observatory on the Puy de Domethe light had been observed between one and two o'clock in themorning; at Mont Ventoux in Provence it had been seen between two andthree o'clock; at Nice it had been noticed between three and fouro'clock; while at the Semnoz Alps between Annecy, Le Bourget, and LeLeman, it had been detected just as the zenith was paling with thedawn.

Now it evidently would not do to disregard these observationsaltogether. There could be no doubt that a light had been observed atdifferent places, in succession, at intervals, during some hours.Hence, whether it had been produced from many centers in theterrestrial atmosphere, or from one center, it was plain that thelight must have traveled at a speed of over one hundred and twentymiles an hour.

In the United Kingdom there was much perplexity. The observatorieswere not in agreement. Greenwich would not consent to the propositionof Oxford. They were agreed on one point, however, and that was: "Itwas nothing at all!"

But, said one, "It was an optical illusion!" While the othercontended that, "It was an acoustical illusion!" And so theydisputed. Something, however, was, it will be seen, common to both"It was an illusion."

Between the observatory of Berlin and the observatory of Vienna thediscussion threatened to end in international complications; butRussia, in the person of the director of the observatory at Pulkowa,showed that both were right. It all depended on the point of viewfrom which they attacked the phenomenon, which, though impossible intheory, was possible in practice.

In Switzerland, at the observatory of Sautis in the canton ofAppenzell, at the Righi, at the Gaebriss, in the passes of theSt. Gothard, at the S

t. Bernard, at the Julier, at the Simplon, atZurich, at Somblick in the Tyrolean Alps, there was a very strongdisinclination to say anything about what nobody could prove--andthat was nothing but reasonable.

But in Italy, at the meteorological stations on Vesuvius, on Etna inthe old Casa Inglesi, at Monte Cavo, the observers made no hesitationin admitting the materiality of the phenomenon, particularly as theyhad seen it by day in the form of a small cloud of vapor, and bynight in that of a shooting star. But of what it was they knewnothing.

Scientists began at last to tire of the mystery, while they continuedto disagree about it, and even to frighten the lowly and theignorant, who, thanks to one of the wisest laws of nature, haveformed, form, and will form the immense majority of the world'sinhabitants. Astronomers and meteorologists would soon have droppedthe subject altogether had not, on the night of the 26th and 27th,the observatory of Kautokeino at Finmark, in Norway, and during thenight of the 28th and 29th that of Isfjord at Spitzbergen--Norwegianone and Swedish the other--found themselves agreed in recording thatin the center of an aurora borealis there had appeared a sort of hugebird, an aerial monster, whose structure they were unable todetermine, but who, there was no doubt, was showering off from hisbody certain corpuscles which exploded like bombs.

In Europe not a doubt was thrown on this observation of the stationsin Finmark and Spitzbergen. But what appeared the most phenomenalabout it was that the Swedes and Norwegians could find themselves inagreement on any subject whatever.

There was a laugh at the asserted discovery in all the observatoriesof South America, in Brazil, Peru, and La Plata, and in those ofAustralia at Sydney, Adelaide, and Melbourne; and Australian laughteris very catching.

To sum up, only one chief of a meteorological station ventured on adecided answer to this question, notwithstanding the sarcasms thathis solution provoked. This was a Chinaman, the director of theobservatory at Zi-Ka-Wey which rises in the center of a vast plateauless than thirty miles from the sea, having an immense horizon andwonderfully pure atmosphere. "It is possible," said he, "that theobject was an aviform apparatus--a flying machine!"

What nonsense!

But if the controversy was keen in the old world, we can imagine whatit was like in that portion of the new of which the United Statesoccupy so vast an area.

A Yankee, we know, does not waste time on the road. He takes thestreet that leads him straight to his end. And the observatories ofthe American Federation did not hesitate to do their best. If theydid not hurl their objectives at each other's heads, it was becausethey would have had to put them back just when they most wanted touse them. In this much-disputed question the observatories ofWashington in the District of Columbia, and Cambridge inMassachusetts, found themselves opposed by those of Dartmouth Collegein New Hampshire, and Ann Arbor in Michigan. The subject of theirdispute was not the nature of the body observed, but the precisemoment of its observation. All of them claimed to have seen it thesame night, the same hour, the same minute, the same second, althoughthe trajectory of the mysterious voyager took it but a moderateheight above the horizon. Now from Massachusetts to Michigan, fromNew Hampshire to Columbia, the distance is too great for this doubleobservation, made at the same moment, to be considered possible.

Dudley at Albany, in the state of New York, and West Point, themilitary academy, showed that their colleagues were wrong by anelaborate calculation of the right ascension and declination of theaforesaid body.

But later on it was discovered that the observers had been deceivedin the body, and that what they had seen was an aerolite. Thisaerolite could not be the object in question, for how could anaerolite blow a trumpet?

It was in vain that they tried to get rid of this trumpet as anoptical illusion. The ears were no more deceived than the eyes.Something had assuredly been seen, and something had assuredly beenheard. In the night of the 12th and 13th of May--a very dark night--theobservers at Yale College, in the Sheffield Science School, hadbeen able to take down a few bars of a musical phrase in D major,common time, which gave note for note, rhythm for rhythm, the chorusof the Chant du Depart.

"Good," said the Yankee wags. "There is a French band well up in theair."

"But to joke is not to answer." Thus said the observatory at Boston,founded by the Atlantic Iron Works Society, whose opinions in mattersof astronomy and meteorology began to have much weight in the worldof science.

Then there intervened the observatory at Cincinnati, founded in 1870,on Mount Lookout, thanks to the generosity of Mr. Kilgour, and knownfor its micrometrical measurements of double stars. Its directordeclared with the utmost good faith that there had certainly beensomething, that a traveling body had shown itself at very shortperiods at different points in the atmosphere, but what were thenature of this body, its dimensions, its speed, and its trajectory,it was impossible to say.

It was then a journal whose publicity is immense--the "New YorkHerald"--received the anonymous contribution hereunder.

"There will be in the recollection of most people the rivalry whichexisted a few years ago between the two heirs of the Begum ofRagginahra, the French doctor Sarrasin, the city of Frankville, andthe German engineer Schultze, in the city of Steeltown, both in thesouth of Oregon in the United States.

"It will not have been forgotten that, with the object of destroyingFrankville, Herr Schultze launched a formidable engine, intended tobeat down the town and annihilate it at a single blow.

"Still less will it be forgotten that this engine, whose initialvelocity as it left the mouth of the monster cannon had beenerroneously calculated, had flown off at a speed exceeding by sixteentimes that of ordinary projectiles--or about four hundred and fiftymiles an hour--that it did not fall to the ground, and that itpassed into an aerolitic stage, so as to circle for ever round our globe.

"Why should not this be the body in question?"

Very ingenious, Mr. Correspondent on the "New York Herald!" but howabout the trumpet? There was no trumpet in Herr Schulze's projectile!

So all the explanations explained nothing, and all the observers hadobserved in vain. There remained only the suggestion offered by thedirector of Zi-Ka-Wey. But the opinion of a Chinaman!

The discussion continued, and there was no sign of agreement. Thencame a short period of rest. Some days elapsed without any object,aerolite or otherwise, being described, and without any trumpet notesbeing heard in the atmosphere. The body then had fallen on some partof the globe where it had been difficult to trace it; in the sea,perhaps. Had it sunk in the depths of the Atlantic, the Pacific, orthe Indian Ocean? What was to be said in this matter?

But then, between the 2nd and 9th of June, there came a new series offacts which could not possibly be explained by the unaided existenceof a cosmic phenomenon.

In a week the Hamburgers at the top of St. Michael's Tower, the Turkson the highest minaret of St. Sophia, the Rouennais at the end of themetal spire of their cathedral, the Strasburgers at the summit oftheir minister, the Americans on the head of the Liberty statue atthe entrance of the Hudson and on the Bunker Hill monument at Boston,the Chinese at the spike of the temple of the Four Hundred Genii atCanton, the Hindus on the sixteenth terrace of the pyramid of thetemple at Tanjore, the San Pietrini at the cross of St. Peter's atRome, the English at the cross of St. Paul's in London, the Egyptiansat the apex of the Great Pyramid of Ghizeh, the Parisians at thelighting conductor of the iron tower of the Exposition of 1889, athousand feet high, all of them beheld a flag floating from some oneof these inaccessible points.

And the flag was black, dotted with stars, and it bore a golden sunin its center.