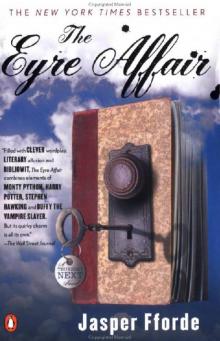

The Eyre Affair tn-1

Jasper Fforde

The Eyre Affair

( Thursday Next - 1 )

Jasper Fforde

Imagine this. Great Britain in 1985 is close to being a police state. The Crimean War has dragged on for more than 130 years and Wales is self-governing. The only recognizable thing about this England is her citizens’ enduring love of literature. And the Third Most Wanted criminal, Acheron Hades, is stealing characters from England’s cherished literary heritage and holding them for ransom.

Bibliophiles will be enchanted, but not surprised, to learn that stealing a character from a book only changes that one book, but Hades has escalated his thievery. He has begun attacking the original manuscripts, thus changing all copies in print and enraging the reading public. That’s why Special Operations Network has a Literary Division, and it is why one of its operatives, Thursday Next, is on the case.

Thursday is utterly delightful. She is vulnerable, smart, and, above all, literate. She has been trying to trace Hades ever since he stole Mr. Quaverley from the original manuscript of Martin Chuzzlewit and killed him. You will only remember Mr. Quaverley if you read Martin Chuzzlewit prior to 1985. But now Hades has set his sights on one of the plums of literature, Jane Eyre, and he must be stopped.

How Thursday achieves this and manages to preserve one of the great books of the Western canon makes for delightfully hilarious reading. You do not have to be an English major to be pulled into this story. You’ll be rooting for Thursday, Jane, Mr. Rochester—and a familiar ending.

The Eyre Affair

by Jasper Fforde

For my father John Standish Fforde (1921-2000)

Who never knew I was to be published but would have been most proud nonetheless—and not a little surprised

1. A woman named Thursday Next

… The Special Operations Network was instigated to handle policing duties considered either too unusual or too specialised to be tackled by the regular force. There were thirty departments in all, starting at the more mundane Neighbourly Disputes (SO-20) and going on to Literary Detectives (SO-27) and Art Crime (SO-24). Anything below SO-2O was restricted information, although it was common knowledge that the ChronoGuard were SO-12 and Antiterrorism SO-9. It is rumoured that SO-1 was the department that polices the SpecOps themselves. Quite what the others do is anyone’s guess. What is known is that the individual operatives themselves are mostly ex-military or ex-police and slightly unbalanced. ‘If you want to be a SpecOp,’ the saying goes, ‘act kinda weird…’

Millon de Floss. A Short History of the Special Operations Network

My father had a face that could stop a clock. I don’t mean that he was ugly or anything; it was a phrase the ChronoGuard used to describe someone who had the power to reduce time to an ultra-slow trickle. Dad had been a colonel in the ChronoGuard and kept his work very quiet. So quiet, in fact, that we didn’t know he had gone rogue at all until his timekeeping buddies raided our house one morning clutching a Seize & Eradication order open-dated at both ends and demanding to know where and when he was. Dad had remained at liberty ever since; we learned from his subsequent visits that he regarded the whole service as ‘morally and historically corrupt’ and was fighting a one-man war against the bureaucrats within the Office for Special Temporal Stability. I didn’t know what he meant by that and still don’t; I just hoped he knew what he was doing and didn’t come to any harm doing it. His skills at stopping the clock were hard-earned and irreversible: he was now a lonely itinerate in time, belonging to not one age but to all of them and having no home other than the chronoclastic ether.

I wasn’t a member of the ChronoGuard. I never wanted to be. By all accounts it’s not a huge barrel of laughs, although the pay is good and the service boasts a retirement plan that is second to none: a one-way ticket to anywhere and anywhen you want. No, that wasn’t for me. I was what we called an ‘Operative Grade I’ for SO-27, the Literary Detective Division of the Special Operations Network based in London. It’s way less flash than it sounds. Since 1980 the big criminal gangs had moved in on the lucrative literary market and we had much to do and few funds to do it with. I worked under Area Chief Boswell, a small, puffy man who looked like a bag of flour with arms and legs. He lived and breathed the job; words were his life and his love—he never seemed happier than when he was on the trail of a counterfeit Coleridge or a fake Fielding. It was under Boswell that we arrested the gang who were stealing and selling Samuel Johnson first editions; on another occasion we uncovered an attempt to authenticate a flagrantly unrealistic version of Shakespeare’s lost work, Gardenia. Fun while it lasted, but only small islands of excitement among the ocean of day-to-day mundanities that is SO-2y: we spent most of our time dealing with illegal traders, copyright infringements and fraud.

I had been with Boswell and SO-2y for eight years, living in a Maida Vale apartment with Pickwick, a regenerated pet dodo left over from the days when reverse extinction was all the rage and you could buy home cloning kits over the counter. I was keen—no, I was desperate— to get away from the LiteraTecs but transfers were unheard of and promotion a non-starter. The only way I was going to make full Inspector was if my immediate superior moved on or out. But it never happened; Inspector Turner’s hope to marry a wealthy Mr. Right and leave the service stayed just that—a hope—as so often Mr. Right turned out to be either Mr. Liar, Mr. Drunk or Mr. Already Married.

As I said earlier, my father had a face that could stop a clock; and that’s exactly what happened one spring morning as I was having a sandwich in a small cafe not far from work. The world flickered, shuddered and stopped. The proprietor of the cafe froze in mid-sentence and the picture on the television stopped dead. Outside, birds hung motionless in the sky. Cars and trams halted in the streets and a cyclist involved in an accident stopped in midair, the look of fear frozen on his face as he paused two feet from the hard asphalt. The sound halted too, replaced by a dull snapshot of a hum, the world’s noise at that moment in time paused indefinitely at the same pitch and volume.

‘How’s my gorgeous daughter?’

I turned. My father was sitting at a table and rose to hug me affectionately.

‘I’m good,’ I replied, returning his hug tightly. ‘How’s my favourite father?’

‘Can’t complain. Time is a fine physician.’

I stared at him for a moment.

‘Y’ know,’ I muttered, ‘I think you’re looking younger every time I see you.’

‘I am. Any grandchildren in the offing?’

‘The way I’m going? Not ever.’

My father smiled and raised an eyebrow.

‘I wouldn’t say that quite yet.’

He handed me a Woolworths bag.

‘I was in ‘78 recently,’ he announced. ‘I brought you this.’

He handed me a single by the Beatles. I didn’t recognise the title.

‘Didn’t they split in ‘70?’

‘Not always. How are things?’

‘Same as ever. Authentications, copyright, theft—‘

‘—same old shit?’

‘Yup.’ I nodded. ‘Same old shit. What brings you here?’

‘I went to see your mother three weeks ahead your time,’ he answered, consulting the large chronograph on his wrist. ‘Just the usual—ahem—reason. She’s going to paint the bedroom mauve in a week’s time—will you have a word and dissuade her? It doesn’t match the curtains.’

‘How is she?’

He sighed deeply.

‘Radiant, as always. Mycroft and Polly would like to be remembered, too.’

They were my aunt and uncle; I loved them deeply, although both were mad as pants. I regretted not seeing Mycroft most of all. I hadn’t returned to my home-town for many years and I di

dn’t see my family as often as I should.

‘Your mother and I think it might be a good idea for you to come home for a bit. She thinks you take work a little too seriously.’

‘That’s a bit rich, Dad, coming from you.’

‘Ouch—that—hurt. How’s your history?’

‘Not bad.’

‘Do you know how the Duke of Wellington died?’

‘Sure,’ I answered. ‘He was shot by a French sniper during the opening stages of the Battle of Waterloo. Why?’

‘Oh, no reason,’ muttered my father with feigned innocence, scribbling in a small notebook. He paused for a moment.

‘So Napoleon won at Waterloo, did he?’ he asked slowly and with great intensity.

‘Of course not,’ I replied. ‘Field Marshal Blьcher’s timely intervention saved the day.’

I narrowed my eyes.

‘This is all O-level history, Dad. What are you up to?’

‘Well, it’s a bit of a coincidence, wouldn’t you say?’

‘What is?’

‘Nelson and Wellington, two great English national heroes both being shot early on during their most important and decisive battles.’

‘What are you suggesting?’

‘That French revisionists might be involved.’

‘But it didn’t affect the outcome of either battle,’ I asserted. ‘We still won on both occasions!’

‘I never said they were good at it.’

‘That’s ludicrous!’ I scoffed. ‘I suppose you think the same revisionists had King Harold killed in 1066 to assist the Norman invasion!’

But Dad wasn’t laughing. He replied with some surprise: ‘Harold? Killed? How?’

‘An arrow, Dad. In his eye.’

‘English or French?’

‘History doesn’t relate,’ I replied, annoyed at his bizarre line of questioning.

‘In his eye, you say—? Time is out of joint,’ he muttered, scribbling another note.

‘What’s out of joint?’ I asked, not quite hearing him. ‘Nothing, nothing. Good job I was born to set it right—‘

‘Hamlet?’ I asked, recognising the quotation. He ignored me, finished writing and snapped the notebook shut, then placed his fingertips on his temples and rubbed them absently for a moment. The world joggled forward a second and refroze as he did so. He looked about nervously.

‘They’re on to me. Thanks for your help, Sweetpea. When you see your mother, tell her she makes the torches burn brighter—and don’t forget to try and dissuade her from painting the bedroom.’

‘Any colour but mauve, right?’

‘Right.’ He smiled at me and touched my face. I felt my eyes moisten; these visits were all too short. He sensed my sadness and smiled the sort of smile any child would want to receive from their father. Then he spoke:

‘For I dipped into the past, far as SpecOps twelve could see–‘

He paused and I finished the quote, part of an old ChronoGuard song Dad used to sing to me when I was a child.

‘—saw a vision of the world and all the options there could be!’

And then he was gone. The world rippled as the clock started again. The barman finished his sentence, the birds flew on to their nests, the television came back on with a nauseating ad for SmileyBurgers, and over the road the cyclist met the asphalt with a thud.

Everything carried on as normal. No one except myself had seen Dad come or go.

I ordered a crab sandwich and munched on it absently while sipping from a Mocha that seemed to be taking an age to cool down. There weren’t a lot of customers and Stanford, the owner, was busy washing up some cups. I put down my paper to watch the TV when the Toad News Network logo came up.

Toad News was the biggest news network in Europe. Run by the Goliath Corporation, it was a twenty-four-hour service with up-to-date reports that the national news services couldn’t possibly hope to match. Goliath gave it finance and stability, but also a slightly suspicious air. No one liked the Corporation’s pernicious hold on the nation, and the Toad News Network received more than its fair share of criticism, despite repeated denials that the parent company called the shots.

‘This,’ boomed the announcer above the swirling music, ‘is the Toad News Network. The Toad, bringing you News Global, News Updates, News NOW!’

The lights came up on the anchorwoman, who smiled into the camera.

‘This is the midday news on Monday, 6th May 1985, and this is Alexandria Belfridge reading it. The Crimean peninsula,’ she announced, ‘has again come under scrutiny this week as the United Nations passed resolution PN17296, insisting that England and the Imperial Russian Government open negotiations concerning sovereignty. As the Crimean War enters its one hundred and thirty-first year, pressure groups both at home and abroad are pushing for a peaceful end to hostilities.’

I closed my eyes and groaned quietly to myself. I had been out there doing my patriotic duty in ‘73 and had seen the truth of warfare beyond the pomp and glory for myself. The heat, the cold, the fear, the death. The announcer spoke on, her voice edged with jingoism.

‘When the English forces ejected the Russians from their last toehold on the peninsula in 1975, it was seen as a major triumph against overwhelming odds. However, a state of deadlock has been maintained since those days and the country’s mood was summed up last week by Sir Gordon Duff-Rolecks at an anti-war rally in Trafalgar Square.’

The programme cut to some footage of a large and mainly peaceful demonstration in central London. Duff-Rolecks was standing on a podium and giving a speech in front of a large and untidy nest of microphones.

‘What began as an excuse to curb Russia’s expansionism in 1854,’ intoned the MP, ‘has collapsed over the years into nothing more than an exercise to maintain the nation’s pride.’

But I wasn’t listening. I’d heard it all before a zillion times. I took another sip of coffee as sweat prickled my scalp. The TV showed stock footage of the peninsula as Duff-Rolecks spoke: Sebastapol, a heavily fortified English garrison town with little remaining of its architectural and historical heritage. Whenever I saw these pictures the smell of cordite and the crack of exploding shells filled my head. I instinctively stroked the only outward mark from the campaign I had—a small raised scar on my chin.

Others had not been so lucky. Nothing had changed. The war had ground on.

‘It’s all bullshit, Thursday,’ said a gravely voice close at hand.

It was Stanford, the cafe owner. Like me he was a veteran of the Crimea, but from an earlier campaign. Unlike me he had lost more than just his innocence and some good friends; he lumbered around on two tin legs and still had enough shrapnel in his body to make half a dozen baked bean tins.

‘The Crimea has got sod all to do with the United Nations.’

He liked to talk about the Crimea with me despite our opposing views. No one else really wanted to. Soldiers involved in the on-going dispute with Wales had more kudos; Crimean personnel on leave usually left their uniforms in the wardrobe.

‘I suppose not,’ I replied non-committally, staring out of the window to where I could see a Crimean veteran begging at a street corner, reciting Longfellow from memory for a couple of pennies.

‘Makes all those lives seem wasted if we give it back now,’ added Stanford gruffly. ‘We’ve been there since 1854. It belongs to us. You might as well say we should give the Isle of Wight back to the French.’

‘We did give the Isle of Wight back to the French,’ I replied patiently; Stanford’s grasp of current affairs was generally confined to First Division pelota and the love life of actress Lola Vavoom.

‘Oh yes,’ he muttered, brow knitted. ‘We did, didn’t we? Well, we shouldn’t have. And who do the UN think they are?’

‘I don’t know but if the killing stops they’ve got my vote, Stan.’

The barkeeper shook his head sadly as Duff-Rolecks concluded his speech:

“… there can be little doubt that the Czar Romanov Alex

ei IV does have overwhelming rights to sovereignty of the peninsula and I for one look forward to the day when we can withdraw our troops from what can only be described as an incalculable waste of human life and resources.’

The Toad News anchorwoman came back on and moved to another item—the government was to raise the duty on cheese to 83 per cent, an unpopular move that would doubtless have the more militant citizens picketing cheese shops.

‘The Ruskies could stop it tomorrow if they pulled out!’ said Stanford belligerently.

It wasn’t an argument and he and I both knew it. There was nothing left of the peninsula that would be worth owning whoever won. The only stretch of land that hadn’t been churned to a pulp by artillery bombardment was heavily mined. Historically and morally the Crimea belonged to Imperial Russia; that was all there was to it.

The next news item was about a border skirmish with the Socialist Republic of Wales; no one hurt, just a few shots exchanged across the River Wye near Hay. Typically rambunctious, the youthful President-for-Life Owain Glyndwr VII had blamed England’s imperialist yearnings for a unified Britain; equally typically, Parliament had not so much as even made a statement about the incident. The news ground on, but I wasn’t really paying attention. A new fusion plant had opened in Dungeness and the Prime Minister had been there to open it. He grinned dutifully as the flashbulbs went off. I returned to my paper and read a story about a parliamentary bill to remove the dodo’s Protected Species status after their staggering increase in numbers; but I couldn’t concentrate. The Crimea had filled my mind with its unwelcome memories. It was lucky for me that my pager bleeped and brought with it a much-needed reality check. I tossed a few notes on the counter and sprinted out of the door as the Toad News anchorwoman sombrely announced that a young surrealist had been killed—stabbed to death by a gang adhering to a radical school of French impressionists.

2. Gad’s Hill