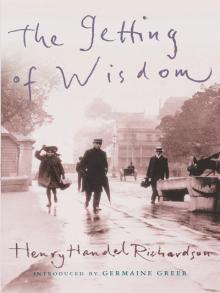

The Getting of Wisdom

Henry Handel Richardson

PRAISE FOR HENRY HANDEL RICHARDSON AND

THE GETTING OF WISDOM

‘What makes this account of Laura Rambotham’s early girlhood a particularly engrossing story is its simplicity, its ability to measure childhood tragedy and excitement with childhood eyes…Miss Richardson reveals here, as in other books, those two great qualities of the born novelist: a love of truth and a gift of deep understanding.’ New York Times Book Review

‘This is a book that everyone should read and nobody can like; its cleverness is astonishing.’ Academy

‘The best of all contemporary school stories is by “Henry Handel Richardson”—a woman.’ Observer

‘The book is calculated to impress very unfavourably those who do not know that the Australian girl is a much cleaner, wholesomer and straighter person than any of the characters portrayed. It is a book we should strongly recommend adults to keep out of the hands of girls.’ British-Australian

‘The Getting of Wisdom races ahead of the reader, succeeding by force of narrative and sheer charm…spontaneity and skill; the values of a whole society are seen here in microcoosm through the lives of pupils and teachers.’ New Statesman

‘Fascinating.’ Times Literary Supplement

OTHER WORKS BY THE AUTHOR

Maurice Guest

The Fortunes of Richard Mahony

Two Studies

The End of a Childhood

The Young Cosima

Myself When Young

the getting

of Wisdom

Henry Handel Richardson

with an introduction by Germaine Greer

TEXT PUBLISHING

MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA

Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson, later known as Henry Handel Richardson, was born in Melbourne in 1870. Her first novel, Maurice Guest, was published in 1908 and The Getting of Wisdom in 1910. In 1932 Richardson was nominated for the Nobel Prize. She died in 1946.

Germaine Greer is a well-known writer and feminist. Her books include The Female Eunuch, Daddy, I Hardly Knew You, The Change, The Obstacle Race and The Boy. She is professor of English and comparative studies at Warwick University, England.

The paper used in this book is manufactured only from wood grown in sustainable regrowth forests.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

www.textpublishing.com.au

Copyright introduction © Germaine Greer 1981

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by William Heinemann 1910

First published by Text Publishing 2000

This edition 2001, reprinted 2005, 2008

Printed and bound by Griffin Press

Designed by Chongwengho

Typeset by Midland Typesetters

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Richardson, Henry Handel, 1870–1946.

The getting of wisdom.

New ed.

ISBN 1 876485 95 7.

1. Historical fiction. I. Greer, Germaine, 1939– . II. Title.

A823.2

To my unnamed little collaborator

Contents

Introduction

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

Introduction

GERMAINE GREER

Henry Handel Richardson was the name in which Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson chose to make her bid for fame as a novelist. The Getting of Wisdom was begun while she was finishing her first published novel, Maurice Guest, as a relief, she wrote in 1940, from that book’s steadily deepening sense of gloom. The nom de plume was assumed, she explained, because ‘there had been much talk in the press about the ease with which a woman’s work could be distinguished from a man’s; and I wanted to try out the truth of the assertion’. The truth of the assertion had been repeatedly tried over the century that had passed since the Brontë sisters had shyly appeared before their public as Ellis, Acton and Currer Bell, only to abandon their pseudonyms with alacrity after they had won recognition. George Eliot succeeded so well in transcending her femaleness that her first novel, Scenes of Clerical Life, had actually been attributed to a Mr Joseph Liggins who did not scruple to profit by the mistake and fooled many people for more than a year. Marian Evans needed her masculine disguise not simply because she wished to write with the breadth and authority considered appropriate only to men, but because she had to shield her scandalous private life, which, if it had become common knowledge, would have undermined the impression of high moral tone for which her books were universally esteemed. Why Henry Handel Richardson should have assumed her more ponderous male mask is not so readily apparent, but once it was assumed she clung to it fiercely and bitterly resented any disclosure of her actual, legal identity.

Any discussion of The Getting of Wisdom must begin with the book out of which it grew. Maurice Guest was published in 1908 and had a modest success, going to its second impression within the twelve-month. The author was then the thirty-eight-year-old wife of J. G. Robertson, the first professor of German at the University of London. It was fifty years since George Eliot had disgusted her most devoted readers by describing to them how Stephen Guest, overcome by lust, had covered Maggie Tulliver’s upraised arm with kisses, but Mrs Robertson’s grand design involved her in going much further than a respectable female novelist could yet permit herself to venture. Henry Handel Richardson meant not only to write in a manner which displayed the masculine virtues of power and authority, she wished also to write the story of a degrading sexual obsession from the point of view of its masculine victim. There was to be no hypocrisy in the telling, for the object of his passion was both in love with and had been abandoned by another man. She would accept him as a substitute and lead him into a maze of depravity while Henry Handel Richardson would keep pace with him all the way, to morgues where female suicides lay destroyed by homosexual lovers, to drunken debauches and the seamy bed of a prostitute, until his suicide, when she would look through his eyes at his last glimpse of this world. To attempt all this as Mrs Robertson would be even now to court disaster in the shape of ridicule; in 1908, she would have been sure to attract limelight of the most unpleasant sort and perhaps to ruin her husband’s career as well. By taking shelter beneath her uncle’s name, Henry Handel Richardson felt secure enough to court prurient speculation by dedicating her book to Louise, in the full awareness that her sluttish anti-heroine, who spends the greater part of the book either in bed or in her dressing-gown, like the preferred subjects of Klimt, sallow, languid and rapacious, is also called Louise. The reader is not born who could resist speculating about such a coincidence, and Henry Handel Richardson, who all her life disingenuously claimed to abhor publicity, had no intention that we should.

The Getting of Wisdom has been called an autobiographical novel, presumably because Richardson dr

ew upon her own experiences at the Presbyterian Ladies’ College in Melbourne and it is comparatively easy to identify Laura Rambotham as Ethel Richardson if only in certain fairly superficial particulars. If the autobiographical element in The Getting of Wisdom has been overemphasised, the simple fact that the protagonist of Maurice Guest is male has obscured the importance of Richardson’s own experiences as a music student in Leipzig and Munich, where she spent most of sixteen years of her life, in the development of her main themes. In later life she was to recall every compliment and encouragement that she received from her teachers, but the picture drawn in Maurice Guest is harsher and truer. The novel is set in the 1890s, when the tide of eager and mostly misguided young people who converged on the cultural centres of Europe was at its height. Although Richardson does not question the ideal of high art for which so many insufficiently gifted students endured hunger, privation and cold, her characterisation of the teachers who made a good livelihood out of them is as damaging a comment. They convey their brutality, arrogance and vulgarity in every jolt of their Prussian voices, while their susceptibilities, to vanity, intemperance, lust, favouritism, greed, jealousy, pettiness, unfairness and boredom, are all pitilessly displayed. What Zola had accomplished in L’Oeuvre, which had stripped the glamour from the French Fine Art establishment, may have provided her inspiration: certainly she fills in the same broad canvas showing a cross-section of the student population of Leipzig in the 1890s, with certain figures whose vicissitudes are traced in detail in the foreground. More shocking than the exploration of Guest’s degradation is the implication of gross cultural fraud which parallels her merciless depiction of the worthlessness of the education afforded middle-class Australian girls.

Like Laura, Maurice Guest must get wisdom, for he comes from four years as a provincial schoolteacher to Leipzig brimful of dreams no less fantastical than hers.

In a vision as vivid as those which cross the brain in a sleepless night, he saw a dark compact multitude wait, with breath suspended, to catch the drops that fell like raindrops from his fingers; saw himself the all-conspicuous figure, as, with masterful gestures, he compelled the soul that lay dormant in brass and strings, to give voice to, to interpret to the many, his subtlest emotions. And he was overcome by a tremulous compassion within himself at the idea of wielding such power over an unknown multitude, at the latent nobility of mind and aim that this power implied.

What he encounters is not exaltation and inspiration but coarseness, greed and ambition, as well as a certain crude energy which sustains the tougher students, of whom he is not one. His teachers have an easy task, for they insist upon technique, wearing him out in tedious exercises for all the hours of daylight. No attempt is made to draw out any latent talent which he might have had, for there is no shortage of gifted students, most of whom seem to have come to Leipzig ready-made. Guest’s function is that of all the foreign students who came to Leipzig in search of a dream. He helps to make the prodigious musical activity of the town possible, by paying for it, paying to attend concerts, paying to be snorted at by his teachers, paying to eat and sleep.

Towering over the hoi polloi of students is the resident genius, who bears some resemblance to a bitter caricature of Richard Strauss. He is a Polish violinist called Schilsky, who can play almost all instruments with great dexterity and is writing a symphonic poem called Zarathustra. He is a dandified cad, a deceiver, seducer and exploiter of women, always hard up and unable to refuse money from any source, loose-mouthed and coarse-grained. His muse is the languid Australian belle-laide, Louise Dufrayer, whose exotic appeal captivates the naive and priggish Maurice Guest, who in his pallid way is as different from the street-wise community around him as the adolescent Laura from her sniggering schoolmates. By dint of coming to her rescue when she is prostrated by Schilsky’s sudden flight from sexual thraldom, Guest becomes Louise’s second string. Her capricious demands on his time and energy destroy whatever slight chance he may have had of distinguishing himself. The more he slides into failure, the more striking the contrast between him and the absent genius, who still holds first place in Louise’s thoughts and feelings, until he becomes for her a mere sexual instrument.

…she brought to bear on their intercourse all her own hard-won knowledge, and all her arts. She drew from her store of experience those trifling, yet weighty details, which, once she has learned them, a woman never forgets…she took advantage of the circumstances in which they found themselves, utilising to the full the stimulus of strange times and places: she fired the excitement that lurked in a surreptitious embrace and surrender, under all the dangers of a possible surprise…Her devices were never-ending. Not that they were necessary; for he was helpless in her hands when she assumed the mastery. But she could not afford to omit one of the means to her end, for she had herself to lash as well as him.

The degeneration of their relationship runs its full course, until jealousy and hatred are its only vital forms. When Guest’s integrity is almost completely derelict, he uncovers a depth of depravity in Louise’s character which disgusts him so uncontrollably that he bashes her, only to expiate this new degradation in her bed. The coup de grâce comes in the form of Schilsky’s return to Leipzig. Louise moves toward him as if Guest’s long agony had never happened.

In order to dispel any lingering hope that great art is not made of such material, Richardson adds a bitterly ironical epilogue. Guest’s suicide is two-years-old gossip. Schilsky, the vulgar voluptuary and kept man, is an avant-garde composer whose works rejoice in names like Uber die Letzten Dinge, and Louise Dufrayer is his lawful wife. At their heels trots another devotee, like Guest, a piano student, who flushes with awareness when Mrs Schilsky’s robe brushes his hand.

The product of all the frenzied human endeavour that was Leipzig, with its exhausted, mad and debauched sacrifices to high art, is the genius, Schilsky, distinguished from other mortals not so much by native talent, which remains an unknown quantity, as by selfishness, ambition, libidinousness and lack of scruple. Richardson does not indicate whether his great works are trumpery or the real thing because when all is said and done, it cannot be said to matter. What she was later to call gloom is in fact artistic nihilism, and it is that rather than the knowing about loveless sex which makes Maurice Guest a profoundly shocking novel.

Maurice Guest is Richardson’s Emma Bovary, but if we cannot care as much for Guest as we do for Bovary, the explanation lies not only in the comparative unwieldiness of Richardson’s prose. It may be a part of her masculine posture that she is committed to supplying proliferating details and supporting scenery and sub-plots which contrast with Flaubert’s apparently effortless government of emphasis and attention, but she is also far less interested in her hero than Flaubert was in Emma Bovary. Far too much of her energy is monopolised by her anti-heroine, whose behaviour is, on the face of it, inexcusable. Louise is drawn too fully to support any hypothesis that the pseudonymous author was the male original of Maurice Guest, for every twist of her ungovernable feelings is faithfully conveyed, while Guest’s male vulnerability remains an idea, rather than a force in the novel. The author actually stands in the relationship of a female confidante to Louise, in something the same way as undeclared female lovers have stood to heterosexual women, for example, Ida Baker to Katherine Mansfield. Richardson was very well aware of the impossibility of ascribing her own understanding of Louise to Guest, and repeatedly steps outside his field of awareness to describe Louise’s motivation, thereby creating an uncomfortable tension between the intimismo of the Louise story and the Zolaësque exposé of the Leipzig music establishment. There is also a clue in one of the parallel sub-plots in the character of Joanna, whose whole life was regulated by her love for her charming younger sister, until she betrayed her by conducting a clandestine affair with Schilsky.

The themes which emerge in Maurice Guest strangled in circumstantial details are also dealt with in The Getting of Wisdom, which is as fresh and loose-limbed in style as th

e earlier book is clogged and crabbed. Because of this lightness of touch, The Getting of Wisdom has been called a light novel, when it is in fact profound, but so gracefully and unselfconsciously so that it makes Maurice Guest seem pretentious and overdrawn. In the shorter novel, every stroke is subordinated to the main design, the enactment of a child’s innocence. Maurice Guest, for all its outspokenness about sex and perversion, is a nineteenth-century novel; in The Getting of Wisdom we are suddenly aware that a tenth of the twentieth is almost over. Richardson herself thought that economy of effect and informality of style would prove to be ephemeral modernities rather than her one true claim to immortality, and tended all her life to undervalue The Getting of Wisdom, saying that her whole intention had been merely to raise a laugh. The laugh she gets, as Samuel Beckett might have said, is the only true laugh, the genuine laugh mirthless. The Getting of Wisdom is a tragedy of the absurd. Its stage is the stage of the absurd, bare, spare, peopled by nobodies. Their apparently inconsequential exchanges are disturbing because they stir our deepest fears, the fears of the inevitability of loss. Thus, in the true absurd fashion, the novel affirms what it appears to deny, our inescapable responsibility for each other, beyond any notion of deserving, which alone makes the whole worth more than the sum of its parts.

Laura Tweedle Rambotham’s journey from up-country to Melbourne is every bit as momentous as Maurice Guest’s pilgrimage to Leipzig, but it means more to the reader who makes the journey with her, as we do not with Guest, from a paradisaical home which is more garden than house, where the animals named by Laura eat from her hand. The brashness of the provincial capital strikes as harshly upon the reader as it does upon Laura, and so we are committed to her from the outset. We view her weaknesses with the same kind of ruefulness as we view our own. At the end of the second chapter, she is a fully defined character (as Guest never becomes), the sort of skinny, pale, intense girl for whom puberty is still far distant at twelve years old. She is the difficult eldest child of an impecunious gentlewoman, replete with inappropriate notions of refinement, who might do well, if only most of the time she were not listening to a different drummer, bursting with unanswerable questions which she dare not ask. The reader passes with her from the blinding light of the Australian outdoors to the penumbra of fake gentility which engulfs the Ladies’ College. The interplay of dazzle and twilight is finely managed throughout the novel. In her red hat and her purple dress, Laura is a child of the light who gropes through the shadowless gloom where her sparkle is to be exchanged for polish, coming hard up against the problems that others have ignored, returning only occasionally to the realm of light where she gulps sustenance before plunging once more.