The Illustrated Walden

Henry David Thoreau

PUBLISHERS’ NOTE

In 1897, with the friendly assistance of Mr. A. W. Hosmer, of Concord, Mass., who supplied photographs for nearly all the illustrations, the publishers issued a Holiday Edition of Walden in two volumes, illustrated with photogravures. The present edition is a reissue of that of 1897, with only such changes as were necessary to bring the whole work into a single convenient volume.

BOSTON, September, 1902.

Thoreau in 1855

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

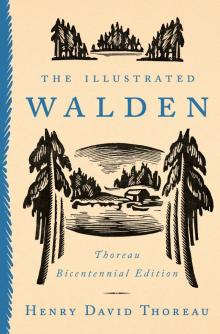

The Illustrated Walden was originally published in 1897 as a two-volume “Holiday Edition” of Walden, and republished in 1902 as a single volume.

First TarcherPerigee edition published 2016.

Tarcher and Perigee are registered trademarks, and the colophon is a trademark of Random House LLC

eBook ISBN 9781101993262

Title page illustration: Ron and Joe/Shutterstock

Cover design: Alison Forner

Cover art: Based on wood engravings by Ethelbert White, originally published in Walden by Henry David Thoreau, Penguin Books, 1938

Version_1

Contents

Publishers’ Note

Title Page

Copyright

List of Illustrations

Introduction by Bradford Torrey

I. Economy

II. Where I Lived, and What I Lived For

III. Reading

IV. Sounds

V. Solitude

VI. Visitors

VII. The Bean-Field

VIII. The Village

IX. The Ponds

X. Baker Farm

XI. Higher Laws

XII. Brute Neighbors

XIII. House-Warming

XIV. Former Inhabitants, and Winter Visitors

XV. Winter Animals

XVI. The Pond in Winter

XVII. Spring

XVIII. Conclusion

Index

List of Illustrations

HENRY D. THOREAU, FROM THE DAGUERREOTYPE TAKEN BY MOXHAM OF WORCESTER IN 1855 OR 1856.

THE HOUSE AT WALDEN, FROM A DRAWING BY CHARLES COPELAND, VIGNETTE ON ENGRAVED TITLE-PAGE.

THOREAU’S BIRTHPLACE

“Born in the Minott house on the Virginia Road, where Father occupied Grandmother’s ‘thirds,’ carrying on the farm. . . . Lived there about eight months.” —Thoreau’s Journal, Dec. 27, 1855.

CONCORD RIVER FROM NASHAWTUC HILL

“The Musketaquid, or Grass-ground River, though probably as old as the Nile or Euphrates, did not begin to have a place in civilized history until the fame of its grassy meadows and its fish attracted settlers out of England in 1635, when it received the other but kindred name of Concord from the first plantation on its banks. . . . To an extinct race it was grass-ground, where they hunted and fished; and it is still perennial grass-ground to Concord farmers, who own the Great Meadows, and get the hay from year to year.”

—A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers.

A. BRONSON ALCOTT

The axe with which Thoreau cleared the ground for his house at Walden was borrowed from Mr. Alcott.

SITE OF THE HOUSE AT WALDEN FROM THE POND

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

Mr. Emerson owned the land on which the Walden house stood. In a letter to him, January 24, 1843, Thoreau wrote: “I have been your pensioner for nearly two years, and still left free as under the sky. It has been as free a gift as the sun or the summer, though I have sometimes molested you with my mean acceptance of it,—I who have failed to render even those slight services of the hand which would have been for a sign at least; and, by the fault of my nature, have failed of many better and higher services. But I will not trouble you with this, but for once thank you as well as Heaven.”

EMERSON’S HOUSE

With profile figure of Mr. Emerson.

FURNITURE USED IN THE WALDEN HOUSE

HENRY D. THOREAU IN 1854, FROM THE ROWSE CRAYON IN THE CONCORD PUBLIC LIBRARY

WALDEN FROM THE HOUSE

The cairn of stones at the left marks approximately the site of the house.

THE OLD MARLBOROUGH ROAD

“If with fancy unfurled

You leave your abode,

You may go round the world

By the Old Marlborough Road.”

—Thoreau, in Excursions.

NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

In the American Note-Books Hawthorne thus records his feeling toward Thoreau: “He is one of the few persons, I think, with whom to hold intercourse is like hearing the wind among the boughs of a forest-tree; and, with all this wild freedom, there is high and classic cultivation in him too.”

PLEASANT MEADOW

“An adjunct of the Baker Farm,” where Thoreau thought of living before he went to Walden.

PINES SET OUT BY THOREAU ON HIS BEANFIELD

HENRY D. THOREAU, from the ambrotype taken by Dunshee of New Bedford, August 19, 1861

SAMUEL STAPLES

Thoreau’s jailer when he was arrested for refusing to pay taxes.

THOREAU’S FLUTE, SPY-GLASS, AND COPY OF WILSON’S ORNITHOLOGY

“Then from the flute, untouched by hands,

There came a low, harmonious breath:

‘For such as he there is no death; —

His life the eternal life commands;

Above man’s aims his nature rose:

The wisdom of a just content

Made one small spot a continent,

And tuned to poetry Life’s prose.’”

—Louisa M. Alcott.

WALDEN POND, SHOWING THE SAND BAR

WHITE POND

BAKER FARM

HENRY D. THOREAU IN 1861, FROM THE MEDALLION BY W. RICKETSON

BRISTER’S SPRING

GREAT MEADOWS

“We . . . floated . . . into the Great Meadows, which, like a broad moccasin print, have leveled a fertile and juicy place in nature.”

—A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers.

(The horseman in the foreground is the sculptor, Daniel C. French.)

CONCORD FROM BRISTER’S HILL

EDMUND HOSMER

The picture below the portrait is a view of the Hosmer house.

WALDEN IN WINTER

SURVEY OF WALDEN POND

GEORGE WILLIAM CURTIS

Those who helped Thoreau raise his house at Walden were Emerson, Alcott, Edmund Hosmer and his three sons John, Edmund, and Andrew, George William Curtis, and Sherman Tuttle,—“the younger men for the liftings, the elders for advice.”

THOREAU’S HOUSE, MAIN STREET, CONCORD, IN WHICH HE DIED

Introduction

T he world likes eccentric people. Not that it wishes to like them; it would feel very differently about them if it could; its prejudices are all in favor of conformity; but the world is never its own master. A worshiper of routine and precedent, it has, nevertheless, a natural relish for variety, and is diverted, like a child, at the sight of something unexpected and out of the common. Its wisdom is prudence. Its rule of life is to keep on the safe side. Follow the path, it says; take no risks. Yet it admires audacity, independence, originality, and, after the event, applauds nothing so much as a violation of its own maxims. Even those who never dream of doing anything that they have not seen some one else do before them are attracted by the sight of a man who consults his own mind; who may surprise

you at any moment with a new idea; for whom to-day’s thought is as good as yesterday’s, and his own thought as credible as one found in a book.

Here, in part, is the secret of Thoreau’s perennial attractiveness. He is so much his own man; and there is so much in him, as the common expression has it. Nobody can tell what he will say next. There is no placing him in a niche and expecting him to stay there. The label put on him to-day will need revision to-morrow. He is so reasonable in many respects, and yet so inconsistent, and so different from the rest of us!

He changed little. From first to last, for aught that appears, he held the same philosophy. He had no awakening, no conversion. His career, inward and outward, was straight as a furrow. The principle of his life was simplicity,—simplicity and economy. But his simplicity was more of a riddle than another man’s complexity.

To begin with, he was a person of strong common sense, handy and practical to the last degree; a capital man to have in the house, as housekeepers say. If something was to be done, he was the one to do it. And it was sure to be done well. When he drove a nail, it would hold. He had an unshakable belief in the everlasting relation of cause and effect,—a kind of sanity not half so general as is commonly assumed; he never dreamed of getting something for nothing. Yet he was a transcendentalist, and though he was an expert surveyor, an excellent gardener, a skillful pencil-maker, and many things beside, he was supposed by his neighbors to deal mostly in moonshine.

In industry, as in frugality, he was a thoroughbred New Englander. Few men in Concord wasted fewer hours. He knew an Irishman, he says, who rose at half past four in the morning, milked twenty-eight cows, and so on to the end of the chapter. “Thus he keeps his virtue in him,” says Thoreau, “if he does not add to it; and he regards me as a gentleman able to assist him; but if I ever get to be a gentleman, it will be by working after my fashion harder than he does.” To his mind a man was bound to be doing something, if it were only marking time in a treadmill. Yet the man who preached thus, and practiced accordingly, was given to spending half of every day wandering about the fields, or rowing on the river.

A naturalist railing against science; an idealist with all the “faculty” of a whittling Yankee; a free-thinking Puritan; a Stoic who sucked sweetness out of all his sensations; a paradox from beginning to end: such was the author of “Walden;” and the world, which is itself a paradox without knowing it, will not soon be done with puzzling itself about him.

Henry David Thoreau was born in Concord, Massachusetts, July 12, 1817. His grandfather, John Thoreau, came from the island of Jersey to America in 1773. He married in Boston, in 1781, a Miss Jane Burns, a Scotchwoman, and in 1800 went to live in Concord. His son, John Thoreau, Junior, married Miss Cynthia Dunbar, also a Scotchwoman,—a New England clergyman’s daughter,—and by her had four children, two sons and two daughters, the third of whom, and the second son, was Henry David. A year or so after Henry’s birth the family moved to Chelmsford, Massachusetts, and later to Boston; but in 1823 they returned to Concord, and there Henry lived till his death, in 1862. Of mixed blood, largely French and Scotch, the author of “Walden” felt himself, nevertheless, a pure New Englander,—a Concord man, native and proper to the soil,—and pronounced his name accordingly, as if it had been the adjective “thorough.”

The American history of the family extends over little more than a century: from 1773, when John Thoreau, Senior, arrived in Boston, to 1881, when Maria Thoreau, the last of his children, died in Bangor, Maine, having outlived all the younger bearers of the name.*

John Thoreau, the elder, we are told, carried on a successful business in Boston, on Long Wharf. His son was bred to the same occupation, but having failed in it, resorted to pencil-making,—an industry already established in Concord,—at which he prospered well enough to leave his family with a “competency” at his death. So Maria Thoreau informed Mr. Sanborn in 1878; but it is probable that the word “competency” is to be taken in some pretty modest sense.

The few anecdotes of Henry Thoreau’s boyhood that have come down to us show him to have been already of a self-respecting and rather stoical turn of mind; not choosing to go to heaven, since he could not take his sled with him, and when falsely accused of theft, answering once for all with a simple denial. It was like the Thoreau of a later time, certainly, to tell the truth and then shut his lips.

The temperaments of the boy’s father and mother were strongly contrasted. The father is described by Mr. Sanborn as “a small, deaf, and unobtrusive man,” “grave and silent, but inwardly cheerful and social.” Mrs. Thoreau, on the other hand, was by all accounts of a peculiarly vivacious temper: “very much of a person,” says Dr. Edward Waldo Emerson, “by no means negative; of Scotch ancestry, a Dunbar, with characteristic keenness, ready wit, economy, and skill of fence with her tongue, all of which, as well as strong family affection, her son Henry inherited from her.” Withal, it is interesting to know, on the same excellent authority, that she “had a great love of nature. It was her constant habit to take her children afield while they were very young. She first directed their attention to birds and flowers, and she and her daughters always had beautiful flowers in a great south window at home during the winter.” She was a “notable housewife,” Dr. Emerson adds, “keeping an excellent table by her skill and taste, even at a time when the family were largely denying themselves butter and sugar that money might be laid by for the boys’ education; and, for all that, she always made home agreeable, not letting herself be drowned in housekeeping and family cares.” Like her son after her, she had a friendly way with children. “I can testify to her exceeding kindness and hospitality to young people, to whom she was a most entertaining hostess,” says Dr. Emerson; “for although she talked fast and much, her wit and mimicry and memory were admirable.”* After this testimony to Mrs. Thoreau’s qualities, it is not difficult to understand why the neighbors of the family always maintained that Henry was “clear Dunbar.” The son, too, held strong opinions, not only about questions of philosophy and politics, but about persons; and these opinions he expressed on occasion with pungency and freedom. What else were opinions for? And he, as well as his mother, was of a social turn. He professed, to be sure, never to have found “the companion that was so companionable as solitude;” a bold saying, at which some readers will sneer, and others grow angry, though there was never a studious, thoughtful man but in certain moods could say the same; but he professed, also, that he was naturally no hermit, and loved society “as much as most.” “He enjoyed common people,” says Channing. “He came to know the inside of every farmer’s house and head, his pot of beans, and mug of hard cider. Never in too much hurry for a dish of gossip, he could sit out the oldest frequenter of the bar-room, and was alive from top to toe with curiosity.” All of which will not be deemed inconsistent with a two years’ life in a woodland hermitage, except by those who demand of human nature a measure of self-consistency that was never in the Maker’s plan.

Of the Thoreau household, as a whole, Mr. Sanborn has drawn a pleasing picture.

“Helen, the oldest child, born in 1812, was an accomplished teacher. John, the elder son, born in 1814, was one of those lovely and sunny natures which infuse affection in all who come within their range; and Henry, with his peculiar strength and independence of soul, was a marked personage among the few who would give themselves the trouble to understand him. Sophia, the youngest child, born in 1819, had, along with her mother’s lively and dramatic turn, a touch of art; and all of them, whatever their accidental position for the time, were superior persons. . . . The household of which they were living and thoughtful members (let one be permitted to say who was for a time domesticated there) had, like the best families everywhere, a distinct and individual existence, in which each person counted for something. . . . To meet one of the Thoreaus was not the same as to encounter any other person who might happen to cross your path. Life to them was something more than a parade of pretensio

ns, a conflict of ambitions, or an incessant scramble for the common objects of desire. . . . Without wealth, or power, or social prominence, they still held a rank of their own, in scrupulous independence, and with qualities that put condescension out of the question.”

At sixteen Henry Thoreau entered Harvard College, the other members of the family cheerfully making sacrifices to that end. His collegiate career, a phrase at which he always smiled, was undistinguished. He carried away no honors, though President Quincy afterward certified that “his rank was high as a scholar in all the branches,” and seems to have made few friends; but he did much reading, and to much purpose, in books of his own choice. One of his fellow students remembers him “in the college yard, with downcast thoughtful look intent, as if he were searching for something;* always in a green coat,—green because the authorities required black, I suppose.”

He was graduated in the regular course at twenty. Then came at once the question of a livelihood. For a time he tried teaching, the first resort of young scholars; but he soon made up his mind against it as too wasteful of time and energy, and seems before long to have settled down upon the conviction, more than once expressed in his books, and consistently adhered to in his practice, that for a scholar bound to remain a scholar—that is, a learner—there is no resource so good as light manual labor. Cut your expenses down till you need to earn little, and earn that little by days’ work, not years’ work, with the hands. This, for substance, was his industrial creed. “Regular” work of any kind, “salaried” work, so called, involves a relinquishment of independence such as would have been fatal to Thoreau’s scheme of life. As for getting a living without earning it, that was something that never entered into his thoughts.

For supporting himself according to his method,—working only when money was needed,—he possessed some very special advantages over the common run of scholars. He had as many trades as fingers, he said. If a few dollars were required, he took a job at surveying, or made lead pencils, or built a fence or a boat, or grafted a neighbor’s fruit trees, or planted a garden. Whatever else he was, he was a born mechanic, “very competent,” as Emerson says of him, “to live in any part of the world.” In a railway car he displayed such address in dealing with an obstinate window that a fellow passenger offered to hire him on the spot; an anecdote which goes with sundry others to show that Thoreau habitually dressed and looked more like a “laboring man” than a scholar.