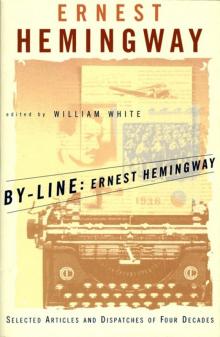

By-Line Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway

Thank you for purchasing this Scribner eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

HEMINGWAY NEEDS NO INTRODUCTION . . .

I. Reporting, 1920–1924

CIRCULATING PICTURES

Circulating Pictures a New High-Art in Toronto

—The Toronto Star Weekly, February 14, 1920

A FREE SHAVE

Taking a Chance for a Free Shave

—The Toronto Star Weekly, March 6, 1920

THE BEST RAINBOW TROUT FISHING

The Best Rainbow Trout Fishing in the World Is at the Canadian Soo

—The Toronto Star Weekly, August 28, 1920

PLAIN AND FANCY KILLINGS, $400 UP

—The Toronto Star Weekly, December 11, 1920

TUNA FISHING IN SPAIN

At Vigo, in Spain, Is Where You Catch the Silver and Blue Tuna, the King of All Fish

—The Toronto Star Weekly, February 18, 1922

THE HOTELS IN SWITZERLAND

Queer Mixture of Aristocrats, Profiteers, Sheep and Wolves in the Hotels in Switzerland

—The Toronto Star Weekly, March 4, 1922

THE SWISS LUGE

Flivver, Canoe, Pram and Taxi Combined in the Luge, Joy of Everybody in Switzerland

—The Toronto Star Weekly, March 18, 1922

AMERICAN BOHEMIANS IN PARIS

American Bohemians in Paris a Weird Lot

—The Toronto Star Weekly, March 25, 1922

GENOA CONFERENCE

Picked Sharpshooters Patrol Genoa Streets

—The Toronto Daily Star, April 13, 1922

RUSSIAN GIRLS AT GENOA

Two Russian Girls the Best-Looking at Genoa Parley

—The Toronto Daily Star, April 24, 1922

FISHING THE RHONE CANAL

There Are Great Fish in the Rhone Canal

—The Toronto Daily Star, June 10, 1922

GERMAN INN-KEEPERS

German Inn-Keepers Rough Dealing with “Auslanders”

—The Toronto Daily Star, September 5, 1922

A PARIS-TO-STRASBOURG FLIGHT

A Paris-to-Strasbourg Flight Shows Living Cubist Picture

—The Toronto Daily Star, September 9, 1922

GERMAN INFLATION

Crossing to Germany Is Way to Make Money

—The Toronto Daily Star, September 19, 1922

HAMID BEY

Hamid Bey Wears Shirt Tucked In When Seen by Star

—The Toronto Daily Star, October 9, 1922

A SILENT, GHASTLY PROCESSION

A Silent, Ghastly Procession Wends Way from Thrace

—The Toronto Daily Star, October 20, 1922

“OLD CONSTAN”

“Old Constan” in True Light Is Tough Town

—The Toronto Daily Star, October 28, 1922

REFUGEES FROM THRACE

Refugee Procession is Scene of Horror

—The Toronto Daily Star, November 14, 1922

MUSSOLINI: BIGGEST BLUFF IN EUROPE

Mussolini, Europe’s Prize Bluffer, More Like Bottomley Than Napoleon

—The Toronto Daily Star, January 27, 1923

A RUSSIAN TOY SOLDIER

Gaudy Uniform Is Tchitcherin’s Weakness: A “Chocolate Soldier” of the Soviet Army

—The Toronto Daily Star, February 10, 1923

GETTING INTO GERMANY

Getting into Germany Quite a Job, Nowadays

—The Toronto Daily Star, May 2, 1923

KING BUSINESS IN EUROPE

King Business in Europe Isn’t What It Used to Be

—The Toronto Star Weekly, September 15, 1923

JAPANESE EARTHQUAKE

Tossed About on Land Like Ships in a Storm

—The Toronto Daily Star, September 25, 1923

BULL FIGHTING A TRAGEDY

Bull Fighting Is Not a Sport—It Is a Tragedy

—The Toronto Star Weekly, October 20, 1923

PAMPLONA IN JULY

World’s Series of Bull Fighting a Mad, Whirling Carnival

—The Toronto Star Weekly, October 27, 1923

TROUT FISHING IN EUROPE

Trout Fishing All Across Europe: Spain Has the Best, Then Germany

—The Toronto Star Weekly, November 17, 1923

INFLATION AND THE GERMAN MARK

German Marks Make Last Stand As Real Money in Toronto’s “Ward”

—The Toronto Star Weekly, December 8, 1923

WAR MEDALS FOR SALE

Lots of War Medals for Sale but Nobody Will Buy Them

—The Toronto Star Weekly, December 8, 1923

CHRISTMAS ON THE ROOF OF THE WORLD

—The Toronto Star Weekly, December 22, 1923

CONRAD, OPTIMIST AND MORALIST

—Transatlantic Review, October, 1924

II. Esquire, 1933–1936

MARLIN OFF THE MORRO: A Cuban Letter

—Esquire, Autumn, 1933

THE FRIEND OF SPAIN: A Spanish Letter

—Esquire, January, 1934

A PARIS LETTER

—Esquire, February, 1934

A. D. IN AFRICA: A Tanganyika Letter

—Esquire, April, 1934

SHOOTISM VERSUS SPORT: The Second Tanganyika Letter

—Esquire, June, 1934

NOTES ON DANGEROUS GAME: The Third Tanganyika Letter

—Esquire, July, 1934

OUT IN THE STREAM: A Cuban Letter

—Esquire, August, 1934

OLD NEWSMAN WRITES: A Letter from Cuba

—Esquire, December, 1934

REMEMBERING SHOOTING-FLYING: A Key West Letter

—Esquire, February, 1935

THE SIGHTS OF WHITEHEAD STREET: A Key West Letter

—Esquire, April, 1935

ON BEING SHOT AGAIN: A Gulf Stream Letter

—Esquire, June, 1935

NOTES ON THE NEXT WAR: A Serious Topical Letter

—Esquire, September, 1935

MONOLOGUE TO THE MAESTRO: A High Seas Letter

—Esquire, October, 1935

THE MALADY OF POWER: A Second Serious Letter

—Esquire, November, 1935

WINGS ALWAYS OVER AFRICA: An Ornithological Letter

—Esquire, January, 1936

ON THE BLUE WATER: A Gulf Stream Letter

—Esquire, April, 1936

THERE SHE BREACHES! or Moby Dick off the Morro

—Esquire, May, 1936

III. Spanish Civil War, 1937–1939

THE FIRST GLIMPSES OF WAR

—NANA Dispatch, March 18, 1937

SHELLING OF MADRID

—NANA Dispatch, April 11, 1937

A NEW KIND OF WAR

—NANA Dispatch, April 14, 1937

THE CHAUFFEURS OF MADRID

—NANA Dispatch, May 22, 1937

A BRUSH WITH DEATH

—NANA Dispatch, September 30, 1937

THE FALL OF TERUEL

—NANA Dispatch, December 23, 1937

THE FLIGHT OF REFUGEES

—NANA Dispatch, April 3, 1938

BOMBING OF TORTOSA

—NANA Dispatch, April 15, 1938

TORTOSA CALMLY AWAITS ASSAULT

—NANA Dispatch, April 18, 1938

A PROGRAM FOR U.S. REALISM

—Ken, August 11, 1938

FRESH AIR ON AN INSIDE STORY

—Ken, September 22, 1938

THE CLARK’S FORK VALLEY, WYOMING

—Vogue,

February, 1939

IV. World War II

HEMINGWAY INTERVIEWED BY RALPH INGERSOLL

Story of Ernest Hemingway’s Far East Trip to See for Himself If War with Japan Is Inevitable

—PM, June 9, 1941

RUSSO-JAPANESE PACT

Ernest Hemingway Says Russo-Jap Pact Hasn’t Kept Soviet from Sending Aid to China

—PM, June 10, 1941

RUBBER SUPPLIES IN DUTCH EAST INDIES

Ernest Hemingway Says We Can’t Let Japan Grab Our Rubber Supplies in Dutch East Indies

—PM, June 11, 1941

JAPAN MUST CONQUER CHINA

Ernest Hemingway Says Japan Must Conquer China or Satisfy USSR Before Moving South

—PM, June 13, 1941

U.S. AID TO CHINA

Ernest Hemingway Says Aid to China Gives U.S. Two-Ocean Navy Security for Price of One Battleship

—PM, June 15, 1941

JAPAN’S POSITION IN CHINA

After Four Years of War in China Japs Have Conquered Only Flat Lands

—PM, June 16, 1941

CHINA’S AIR NEEDS

Ernest Hemingway Says China Needs Pilots as Well as Planes to Beat Japanese in the Air

—PM, June 17, 1941

CHINESE BUILD AIR FIELD

Ernest Hemingway Tells How 100,000 Chinese Labored Night and Day to Build Huge Landing Field for Bombers

—PM, June 18, 1941

VOYAGE TO VICTORY

—Collier’s, July 22, 1944

LONDON FIGHTS THE ROBOTS

—Collier’s, August 19, 1944

BATTLE FOR PARIS

—Collier’s, September 30, 1944

HOW WE CAME TO PARIS

—Collier’s, October 7, 1944

THE G. I. AND THE GENERAL

—Collier’s, November 4, 1944

WAR IN THE SIEGFRIED LINE

—Collier’s, November 18, 1944

V. After the Wars, 1949–1956

THE GREAT BLUE RIVER

—Holiday, July, 1949

THE SHOT

—True, April, 1951

THE CHRISTMAS GIFT

—Look, April 20, May 4, 1954

A SITUATION REPORT

—Look, September 4, 1956

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

INDEX

Hemingway needs no introduction . . .

ERNEST HEMINGWAY, the best-known writer of his generation, needs no introduction to readers today. But this volume, made up of less than one third of the identifiable prose he wrote for newspapers and magazines between 1920 and 1956, does need a few words of explanation. Early in his career, some time before 1931, Hemingway wrote to his bibliographer, Louis Henry Cohn, that the “newspaper stuff I have written . . . has nothing to do with the other writing which is entirely apart . . . . The first right that a man writing has is the choice of what he will publish. If you have made your living as a newspaperman, learning your trade, writing against deadlines, writing to make stuff timely rather than permanent, no one has any right to dig this stuff up and use it against the stuff you have written to write the best you can.”

This is a perfectly reasonable attitude for a novelist or creative writer to take in distinguishing between his fiction and his newspaper reporting. Yet in his more than forty years of writing, not only did Hemingway use the very same material for both news accounts and short stories: he took pieces he first filed with magazines and newspapers and published them with virtually no change in his own books as short stories. For example, two pieces, “A Silent, Ghastly Procession” and “Refugees from Thrace” are news reports (for The Toronto Daily Star) based on experiences he was later to use in In Our Time (1930), where he wrote:

“The Greeks were nice chaps too. When they evacuated they had all their baggage animals they couldn’t take off with them so they just broke their forelegs and dumped them into the shallow water. All those mules with their forelegs broken and pushed over into the shallow water. It was all a pleasant business. My word yes a most pleasant business.”

The same material turns up again in “On the Quai at Smyrna” in The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories (1938) and a few other places. Another Toronto Star “news story,” “Christmas on the Roof of the World,” which is included in the present collection, was privately printed (not by Hemingway) as Two Christmas Tales (1959). But the blurring of the distinction between his news writing and his imaginative writing is most evident in these three instances: “Italy, 1927,” a factual account of a motor trip through Spezia, Genoa and Fascist Italy, first published in The New Republic (May 18, 1927) as journalism, then used as a short story in Men Without Women (1927) with a new title, “Che Ti Dice La Patria,” and in The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories (1938); “Old Man at the Bridge,” cabled as a news dispatch from Barcelona and published in Ken (May 19, 1938) and also put into the First Forty-Nine Stories without even a new title; and “The Chauffeurs of Madrid,” originally sent on May 22, 1937, by the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA) to subscribers of its foreign service as part of Hemingway’s coverage of the Spanish Civil War, and which was included by Hemingway in Men at War (1942), which he edited and subtitled “The Best War Stories of All Time.” (What did he mean by “stories”?) Hemingway also used in the same collection the Caporetto passages from A Farewell to Arms and the El Sordo sequence from For Whom the Bell Tolls. As Chaucer liked to say, “What nedeth wordes mo?”

As a reporter and foreign correspondent in Kansas City (before World War I), Chicago, Toronto, Paris among the expatriates, the Near East, in Europe with the diplomats and statesmen, in Germany and Spain, Hemingway soaked up persons and places and life like a sponge: these were to become matter for his short stories and novels. His use of this material, however, sets him apart from other creative writers who, as he himself says, made their living as journalists, learning their trade, writing against deadlines, writing to make stuff timely rather than permanent. Hemingway, no matter what he wrote or why he was writing, or for whom, was always the creative writer: he used his material to suit his imaginative purposes. This does not mean that he was not a good reporter, for he showed a grasp of politics and economics, was an amazing observer, and knew how to dig for information. But his craft was the craft of fiction, not factual reporting. And though he wrote as he saw things, his writing shows most vividly how he felt about what he saw. If the details were sometimes slighted, the picture as a whole—full of the emotional impact of the events on the people—was clear, lucid and full. For the picture as a whole was what Hemingway the artist cared about.

In selecting the 77 articles in the present volume, I have not limited myself to “uncollected” material, for many of the Toronto Star pieces appear in Hemingway: The Wild Years (1962), edited by Gene Z. Hanrahan; “Marlin off the Morro” (Esquire) in American Big Game Fishing (1935), edited by Eugene V. Connett; “A. D. in Africa” (Esquire) in Fun in Bed: Just What the Doctor Ordered (1938), edited by Frank Scully; “Remembering Shooting-Flying” (Esquire) in Esquire’s First Sports Reader (1945), edited by Herbert Graffis; “On the Blue Water” (Esquire) in Blow the Man Down (1937), edited by Eric Devine; “Notes on the Next War” and “The Malady of Power” (Esquire) as outstanding essays in American magazines in American Points of View 1934–1935 (1936) and American Points of View 1936 (1937), edited by William H. and Kathryn Coe Cordell; “The Clark’s Fork Valley, Wyoming” (Vogue) in Vogue’s First Reader (1942), with an introduction by Frank Crown-inshield; “A New Kind of War” (NANA) in A Treasury of Great Reporting (1949), edited by Louis L. Snyder and Richard B. Morris; and “London Fights the Robots,” (Collier’s) in Masterpieces of War Reporting: The Great Moments of World War II (1962), edited by Louis L. Snyder.

The 29 selections (in Section I) from Hemingway’s 154 in the Toronto Daily Star and Star Weekly represent his first contribution and the best of his work for those papers. The last piece in the section was written in Paris after he left journalism and launched his career as

a short-story writer. By the time he was writing his “letters” almost every month in the 1930’s for Esquire—which make up the second section—this career was at its height. Of Hemingway’s 31 contributions to Esquire I have chosen 17; however, of the remaining 14, six are fiction, outside the scope of my collection.

The NANA dispatches, nine of which I have chosen from the 28 he cabled from Europe, represent Hemingway’s return to professional newspaper reporting during the Spanish war. In this third section I also have two articles (out of 14) he wrote for Ken, an anti-Fascist magazine edited by Arnold Gingrich; they are not up to the quality of “Old Man at the Bridge,” but they are examples of the sort of thing he wrote for almost every issue of this periodical. Although “The Clark’s Fork Valley, Wyoming,” from Vogue, has nothing to do with the Spanish war, it is in this section because of its 1939 date. It is clearly a change-of-pace item and represents Hemingway’s continuing interest in fishing, hunting, and the out-of-doors. Every section in the book—except for the one on World War II—has such an article by Hemingway the naturalist, the hunter, the fisherman.

Section IV is made up of eight articles from the short-lived ad-less New York newspaper PM, written in 1941, and six reports he wrote for Collier’s in 1944 as the chief of their European Bureau—“only enough to keep from being sent home.” These PM dispatches, the work of a mature observer on his first Oriental trip, six months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, show Hemingway’s grasp of things to come; for he predicted that Japan’s attack on British and American bases in the Pacific and southeast Asia would force us into the war. Datelined Hong Kong, Rangoon, and Manila, they were all written from notes made abroad after his return to New York. His seven by-lined news stories and the interview by Ralph Ingersoll, which Hemingway edited, are an excellent analysis of the military situation, but they contrast somewhat with his other war correspondence, for the Toronto Star, NANA, and Collier’s, which emphasizes people and places instead of politics. When Hemingway finally got back to Europe for Collier’s, his escapades led to his being investigated and cleared by army authorities—for violating the Geneva Convention. Of more significance from a journalism standpoint is the fact that his second Collier’s article, “London Fights the Robots,” was chosen in 1962 as one of the “masterpieces of war reporting” by history professor Louis L. Snyder.

For the last section of By-Line: Ernest Hemingway I have a fishing article from Holiday and a hunting article from a men’s magazine, True; Hemingway’s own account in Look of what happened in his near-fatal plane crashes in Africa in 1954; and more about the author himself and his writing in a later Look article of 1956.