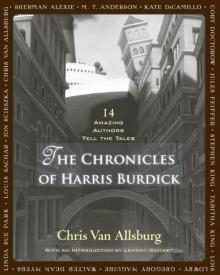

The Chronicles of Harris Burdick: 14 Amazing Authors Tell the Tales

Chris Van Allsburg

Table of Contents

Title Page

Table of Contents

Dedication

Copyright

An Introduction by Lemony Snicket

Archie Smith, Boy Wonder

Under the Rug

A Strange Day in July

Missing in Venice

Another Place, Another Time

Uninvited Guests

The Harp

Mr. Linden's Library

The Seven Chairs

The Third-Floor Bedroom

Just Desert

Captain Tory

Oscar and Alphonse

The House on Maple Street

Original Introduction to The Mysteries of Harris Burdick

About the Authors

For Peter Wenders, again

Text copyright © 2011 by Lemony Snicket, Tabitha King, Jon Scieszka, Sherman Alexie,

Gregory Maguire, Cory Doctorow, Jules Feiffer, Linda Sue Park, Walter Dean Myers, Lois

Lowry, Kate DiCamillo, M. T. Anderson, Louis Sachar, Chris Van Allsburg

Illustrations copyright © 1984 by Chris Van Allsburg

The House on Maple Street © 1993 by Stephen King. Reprinted with the permission of Scribner,

a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., from Nightmares & Dreamscapes by Stephen King. All rights

reserved.

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this

book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park

Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Houghton Mifflin Books for Children is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Publishing Company.

www.hmhbooks.com

The text of this book is set in Centaur MT.

Book design by Sheila Smallwood

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file.

ISBN 978-0-547-54810-4

Manufactured in Singapore

TWP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

4500298309

An Introduction by Lemony Snicket

Is there any author more mysterious than Harris Burdick?

Modesty prevents me from answering this rhetorical question, but the fact remains that Harris Burdick has cast a long and strange shadow across the reading world, not unlike a man, lit by the moon, hiding in the branches of a tree, staring through a window and holding a rare and sinister object, who cast a long and strange shadow across your bedroom wall just last night.

The story of Harris Burdick is a story everybody knows, though there is hardly anything to be known about him. More than twenty-five years ago, a man named Peter Wenders was visited by a stranger who introduced himself as Harris Burdick and who left behind fourteen fascinating drawings with equally if not more fascinating captions, promising to return the next day with more illustrations and the stories to match. Mr. Wenders never saw him again, and for years readers have pored breathlessly over Mr. Burdick's oeuvre, a phrase that here means "looked at the drawings, read the captions, and tried to think what the stories might be like." The result has been an enormous collection of stories, produced by readers all over the globe, imagining worlds of which Mr. Burdick gave us only a glimpse.

I always had a theory regarding Mr. Burdick's disappearance, however, that I have lacked the courage to share until today. It seemed to me that the mysterious author was hiding—but not in the places people usually hide, such as underneath the bed or behind the coats in the closet or in the middle of a field covered in a blanket that looks like grass. Mr. Burdick likely hid among his cohorts, a word that here means "other people in his line of work." Rather than give any more of his work to Mr. Wenders, Mr. Burdick might have distributed his stories, over a period of many years, among his comrades in literature. Perhaps he gave them as gifts in acknowledgment of their allowing him to hide in their homes. Perhaps he hid them in their guest rooms in the hopes that they would never be found. In any case, it was always my hope that the rest of Mr. Burdick's work would surface, even if the mysteries of Mr. Burdick—who by now is either very old, quite dead, or both—remained unsolved.

This book, then, is suspicious. The stories you find here may have been written, as so many Burdick stories have been written, as the guesswork of authors drawn to Mr. Burdick's striking images and captions. But I believe these are the actual stories written by Harris Burdick, given by Burdick to the various authors who are now pretending to have written them. I have no proof of this theory, but when I questioned the authors involved, their answers did nothing to change my mind. Sherman Alexie told me it was none of my business. Jules Feiffer told me it was none of my concern. Lois Lowry told me she'd never heard anything so ridiculous in all her life. Louis Sachar told me he'd heard something equally ridiculous but that it was a very long time ago. Kate DiCamillo told me to talk to her lawyer. M. T. Anderson told me to talk to his doctor. Tabitha King told me to talk to her husband. Stephen King told me to talk to his wife. Cory Doctorow told me I should ask Walter Dean Myers, who told me to go bother Linda Sue Park, who directed me to Gregory Maguire, who told me that he had a special message from Chris Van Allsburg, which was to go away and leave him alone and stop talking about Harris Burdick. Finally, Jon Scieszka told me that he would be happy to answer my questions, and to please come in and have some ice cream, and then after a long pause he fled through the window and left me alone and it turned out to be sherbet.

Perhaps it doesn't matter. Perhaps these stories were written by Harris Burdick and perhaps they were not. Either way, the mysteries of Harris Burdick continue, and if you open this book, you will likely be mystified yourself. As you reread the stories, stare at the images, and ponder the mysteries of Harris Burdick, you will find yourself in a mystery that joins so many authors and readers together in breathless wonder.

Archie Smith, Boy Wonder

A tiny voice asked, "Is he the one?"

ARCHIE SMITH, BOY WONDER

TABITHA KING

Archie squinted into the glare of the sun as he choked the neck of the bat. He pulled his helmet down to get what little shade the visor gave. With his bad luck, the ball would be coming straight out of the sun, which seemed to sit on the runty little pitcher's shoulder. His palms were wet and gritty against the smooth ash of the slugger. His scalp, itchy and sweaty under the helmet.

The pitcher was shorter than he was. All the pitchers were. His bad luck again, he was the biggest kid in the league. It was a weird kind of leverage for them; if they sank the ball enough, it would come in at the low edge of his strike zone.

He thought about Luke in Star Wars, wielding his Jedi lightsaber against a tiny sphere of light. He took a deep breath and waited.

Behind him, the catcher tensed.

Not yet, thought Archie, his grip tightening, and then he thought, Now and his arm drew back just as a tiny sphere of light broke out of the sun. The ball met his bat with a glorious CRACK! and spun away back into the glare.

He stared after it even as the bat fell from his hand and he pushed off, the toes of his Converse All Stars digging into the dirt. There was no following it; that baby was gone. He reached first base, looking to make sure his foot touched it, but then he couldn't help looking up toward where the ball had disappeared as he ran all the way around the bases. He was running hard enough to make his chest tight, and he could hear people yelling to slow down—he could stroll if he wanted—but you don't do it that way, you always play all out, so he kept on running, tagging each base carefully and finally throwin

g himself down across home, so no one could ever dispute that he owned it.

Coach, who was kind of a goof, grabbed him and hugged him and pounded his back, screaming, "You put that one over the moon!" He screamed it three or four times as if nobody had heard him the first time.

Archie didn't need Coach to tell him what he had done. He was Archie Smith, Boy Wonder. Just like his mom said. There she was, jumping up and down and celebrating for him. He knew he was grinning too much and looked stupid, so he tried not to, but he couldn't help it. So what if people laughed at him because they thought he looked funny. So what, his mom always said. So what! When Archie wondered why she said it so often, in so many different ways, turning it into a joke, she said she got it from Metallica, this metal band his dad used to like.

Later that night, punching up his pillow, he replayed the homer in his head. He could just hear the baseball game in the park two blocks west. The moon was full; they hardly needed the lights. There was something really cool and magic about the idea: baseball by moonlight.

It was a grownups' game, guys from the bottling plant versus off-duty cops. Archie's mom had let him watch three innings and then he had had to come home and go to bed, on account of he had summer school tomorrow. His bad luck, special ed kids, him and a bunch of other dorks who had to go to school all year round because they were extra stupid. At least he could walk to school and didn't have to ride the short bus or wear a helmet all the time like a couple of the eds. His mom said that he wasn't stupid, that he was in special ed because he was dickslektic. He knew the correct spelling now but always thought of it the way he first heard it.

He had a desk calendar that had a big word to learn every day, and it was really cool, but he pretended he hated it, just to fool his mom because she was tough to fool.

He liked to watch the grownups play ball. They swore and yelled at each other and there was a yeasty smell of beer in the air. He wondered if the huge moon would ever sink into the pitcher's shoulder so that the ball would seem to come out of the moon. It was cool white, not hot yellow like the sun, so maybe the ball would move slow and smooth like cream when his mom was whipping it. Maybe it would be frosty cold to the touch, coming all the way from the moon through the night of outer space without the sun's heat pushing it like a fiery bat.

Impossible. Of course the moon was rising, so it was already higher than the pitcher's shoulder. The game would have to go on into tomorrow morning before the moon got low enough to sit on anybody's shoulder. It would probably sink to the top of some trees and sit there like a stuck balloon. The thought made him snicker. In his mind he moved the stars around into a baseball diamond.

Somewhere beyond the moon, a bat stopped a baseball with that beautiful CRACK! and Archie was back at the plate, feeling the force of the ball meeting the counterforce of the bat, the jolt starting in his wrist and moving along his arm back to where his shoulders were still swinging the bat. His whole body twisted as he threw himself against the driving force of the ball, his All Stars digging for leverage in the dirt and losing it; he was lifted right off the ground and hung there an instant while his heart stood still, like a big hand stopping the ball right there in midair. He hoped his mom didn't know about his heart stopping. The ball reversed itself, the bat busted thin air, and he came down on top of the catcher. He scrambled up, trying to see the ball, but it was gone or had burst into flame and become the sun. He closed his eyes against the coruscating light, but he could still see it through his shut-tight eyelids.

A tiny voice asked, "Is he the one?"

He pretended to be asleep; it was easy to do, just breathe long and slow so his mom would think he was conked right out like you had been hit by a foul ball.

"Who else?" a second tiny voice replied. "There's your Archie Smith, Boy Wonder, all right."

This voice had a different, well, range of colors to it, so he could tell it from the first voice.

The first tiny voice seemed to laugh; actually it sort of went incandescent, like a cap sparking off under a blow from a rock; pop and fizz.

"Why's he such a Wonder?" the second voice asked in its own crackly burst of color.

"His mom says so," said the first tiny voice.

They laughed together, so all the colors spilled and mingled like inks in a bowl.

He could see them through his lids, popping and fizzing and floating just over his head.

"It's because I always say 'I wonder' all the time," he wanted to tell them, but his throat and tongue were as numb as when the dentist gave him a shot in his gums.

"What does he mean: 'I always say "I wonder" '?" the second voice asked.

Archie thought: They can read my mind.

"Oh," said the first tiny voice, "he says, 'I wonder if I should wear my Boston Red Sox T-shirt today,' or 'I wonder if Miss Loomis will call on me to do my five-times,' or 'I wonder why regular kids have edges on their faces and big starey eyes,' or 'I wonder where baseballs go when they get slammed out of Fenway. I wonder if some lucky kid ever finds them.'"

Sometimes when Archie was pretending to be asleep for his mom and she looked too close when she bent over to kiss him, he would start laughing. His mom would laugh too, at his attempt to fool her. That was what happened now; his throat and tongue were all of a sudden okay. But he didn't open his eyes; the more he wanted to laugh, the tighter he squeezed his eyes closed.

"Bottom of the ninth," the second tiny voice fizzed, and he thought he heard a whole crowd of tiny voices popping and sparking and scintillating. Not very far away, either, maybe just outside his bedroom window, in the warm early summer night.

"Oh," said the first tiny voice, and he felt its fizzing and popping suddenly very close to his ear, almost inside it. "You should always wear your Red Sox T-shirt, if it's clean; Miss Loomis certainly will call on you to do your five-times, so you better work hard on them; regular kids don't have any choice about being regular, they just are, and every single one of them secretly thinks they look funny too; and once in a while, some lucky kid finds a ball that's been knocked out of Fenway, unless the moon's caught it and hurled it back, trying to tag the runner."

"Play ball!" cried the second tiny voice.

CRACK! And a ripple of CRACK!s like ice breaking up on the river in spring; cheers erupt from the park. Sparklers bursting into every crystal color in the universe.

Opening his eyes, Archie sat up and stared out the window, watching moonlets streak like shooting stars across the sky, headed for the moon, laughing on the billows of the summer trees. Slowly, one hand behind his head, he let himself down onto his pillow. Looking at the shadowy ceiling over his bed, he wondered. He wondered if his mom might let him go to the park tomorrow to look in the bushes for a baseball, maybe one the moon dropped, trying for the tag.

Under the Rug

Two weeks passed and it happened again.

UNDER THE RUG

JON SCIESZKA

You should always listen to your grandma. It might save a life.

Grandmas say a lot of crazy things. Things like...

Look before you leap.

If the shoe fits, wear it.

Sit up straight.

So you never know what is really good advice and what is just crazy-talk. But grandmas know a lot. You should listen to them.

I should have listened to my grandma.

***

It started on Wednesday, five Wednesdays ago. I know it was Wednesday because Wednesday is sweeping day. Every Wednesday we sweep the house. Grandma and I. Grandma sweeps the kitchen. I sweep the living room.

At breakfast that morning, five Wednesdays ago, Grandma told me:

Hunger is the best sauce.

Let sleeping dogs lie.

That sweater and bow tie make you look like an old man.

I was sweeping and thinking that I like my sweater, I like my bow tie. Which is probably why I forgot the other thing Grandma always says:

Never sweep a problem under the rug.

I

finished sweeping the living room. I put away the dustpan. I was just walking into the kitchen ... when I saw the dust bunny under the couch. I swept the dust bunny under the rug.

And I didn't give it another thought until the next Wednesday. That morning Grandma said:

Never say never.

Don't count your chickens before they hatch.

What happened to that cake that was on the table?

In the living room, I swept up a trail of cake crumbs that disappeared under the rug. I lifted up the rug. The trail led straight to a clump of hair and crumbs and dust and two glowing red eyes that looked very angry.

The dust bunny had grown into a Dust Tiger!

I dropped the rug.

I couldn't tell Grandma, so I put the end table over the lump in the rug.

***

That worked sort of okay for about a week. Then the cat food started to disappear. Something got into the garbage under the sink.

I tiptoed into the living room. I peeked under the rug.

I saw a huge twisted knot of hair, dirt, liver-flavored Kibbles 'n Bits pieces, coffee grounds, orange peels, two chicken bone horns ... and those angry red eyes staring hungrily at me.

The Dust Tiger had grown into a Dust Devil!

I dropped the rug in a panic.

The lump I had swept under the rug heaved. The lump growled.

I knew I had to take the bull by the horns. I had to strike while the iron was hot. I had to make hay while the sun was shining.

I dragged the bookcase over and dropped it on the bulge in the rug. Something squeaked. Something groaned. Then it was quiet.

The bookcase leaned against the wall a bit crooked, but everything was fine. Everything was fine.