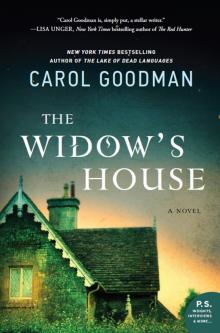

The Widow's House

Carol Goodman

Dedication

For Lee

Epigraph

And now the flight

of sea hawks hints at pterodactyl blood

while ancient sunlight shimmers on the bay,

and our thoughts turn to love, which if it lasts

a year will flirt with immortality.

Vesuvius has nothing new to say,

haze-shrouded, calm. This all goes by so fast.

There’s more than one kind of catastrophe.

—LEE SLONIMSKY, “SEASIDE BENCH, SORRENTO”

Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Acknowledgments

P.S. Insights, Interviews & More . . .* About the author

About the book

Praise

Also by Carol Goodman

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One

When I picture the house I see it in the late afternoon, the golden river light filling the windows and gilding the two-hundred-year-old brick. That’s how we came upon it, Jess and I, at the end of a long day looking at houses we couldn’t afford.

“It’s the color of old money,” Jess said, his voice full of longing. He was standing in the weed-choked driveway, his fingers twined through the ornate loops of the rusted iron gate. “But I think it’s a little over our ‘price bracket.’”

I could hear the invisible quotes around the phrase, one the Realtor had used half a dozen times that day. Jess was always a wicked mimic and Katrine Vanderberg, with her faux country quilted jacket and English rubber boots and bright yellow Suburban, was an easy target. All she needs is a hunting rifle to look like she strode out of Downton Abbey, he’d whispered in my ear when she’d come out of the realty office to greet us. You’d have to know Jess as well as I did to know it was himself he was mocking for dreaming of a mansion when it was clear we could hardly afford a hovel.

It had seemed like a good idea. Go someplace new. Start over. Sell the (already second-mortgaged) Brooklyn loft, pay back the (maxed-out) credit cards, and buy something cheap in the country while Jess finished his book. By country, Jess meant the Hudson Valley, where we had both gone to college, and where he had begun his first novel. He’d developed the superstition over the last winter that if he returned to the site where the muses had first spoken to him he would finally be able to write his long-awaited second novel. And how much could houses up there cost? We both remembered the area as rustic: Jess because he’d seen it through the eyes of a Long Island kid and me because I’d grown up in the nearby village of Concord and couldn’t wait to get out and live in the city.

Since we’d graduated, though, 9/11 had happened and property values in exurbia had soared. The rustic farmhouses and shabby chic Victorian cottages we’d looked at today cost more than we’d get for the sale of our Brooklyn loft and Jess had immediately rejected the more affordable split-levels and sixties suburban ranches Katrine showed us.

“They remind me of my dismal childhood,” he said, staring woefully at the avocado linoleum of a Red Hook faux Colonial.

“There’s one more place I think you should see,” Katrine had said after Jess refused to get out of the car at a modular home. She’d turned the Suburban off Route 9G toward River Road. For a second I thought she was driving us toward the college and I tensed in the backseat. Jess might want to live in the area where we had gone to school, but he didn’t want to see those young hopeful college students loping along the shaded paths of Bailey College. At least not until he’d finished the second novel and he was invited back to do a reading.

But Katrine turned south, away from the college, and I heard Jess in the front seat sigh as we entered the curving tree-lined road. This was what I knew he had in mind when he talked about moving to the country: dry-laid stone walls covered with moss, ancient sycamores with bark peeling off like old wallpaper, apple orchards, clapboard Victorian farmhouses, and, through the gaps in the trees, glimpses of stately mansions and the blue ridges of the Catskills beyond the river. The road itself was filled with the light of a Hudson River school painting. I could see it reflected in Jess’s face, replacing the sallow cast it had taken on this winter as he’d labored over his long-unfinished work. Or the “unborn monster,” as he’d christened it. If only there were something we could afford on this road, but even the dreary farmhouse I’d grown up in was surely out of our price range.

When we pulled into a weed-choked driveway and parked outside a rusted gate, though, I immediately recognized where we were and thought Katrine had misunderstood our situation. Lots of people did. Jess was, after all, a famous writer. The first book had done well enough—and he’d been young and photogenic enough—to get his picture in Granta and Vanity Fair. He’d gotten a high-six-figure advance for the second novel—but that was ten years ago. The advance was long gone; the second novel was still incomplete.

But Jess had already gotten out, drawn by that golden river light, and gone to stand at the iron gate to gaze up at the house. Silhouetted against the afternoon light, so thin and wiry in his black jeans and leather jacket, he looked like part of the iron scrollwork. How thin he’s grown this winter, I thought. The late afternoon sun turned Jess’s hair the red gold it had been when we first met in college, banishing the silver that had begun, not unattractively, to limn his temples. His eyes were hidden behind dark sunglasses, but I could still read the longing in his face as he gazed up at the house. And who wouldn’t long for such a house?

It stood on a rise above a curve in the river like a medieval watchtower. The old brick was mellowed with age and warmed from centuries of river light, the windows made from wavy cockled glass with tiny bubbles in it that held the light like good champagne. The sunken gardens surrounding an ornamental pond were already cool and dark, promising a dusky retreat even on the hottest summer day. For a moment I thought I heard the sound of glasses clinking and laughter from a long-ago summer party, but then I realized it was just some old wind chimes hanging from the gatehouse. There hadn’t been any parties here for a while. When the sun went behind a cloud and the golden glow disappeared my eyes lingered more on the missing slate tiles in the roof, the weeds growing up between the paving stones of the front flagstones, the paint peeling off the porch columns, and the cracked and crumbling front steps. I even thought I could detect on the river breeze the smell of rot and mildew. And when Jess turned, his fingers still gripping the gate, I saw that without that light his face had turned sallow again and the look of longing was replaced with the certainty that he would always be on the wrong side of that gate. That’s how he had become such a good mimic, by watching and listening from the other side. It made my heart ache for him.

“No, not in our ‘price bracket’ I think.”

If

Katrine noticed his mocking tone she didn’t let on. “It isn’t for sale,” she said. “But the owner’s looking for a caretaker.”

If I could have tackled her before the words were out of her mouth, I would have, but the damage was already done. Jess’s face had the stony look it got when he was getting ready to demolish someone, but as he often did these days he turned the rancor on himself. “I’ve always fancied myself a bit of a Mellors.”

I was about to jump in and tell Katrine that Mellors was the caretaker in a D. H. Lawrence novel but she was laughing as if she’d gotten the reference. “That’s just the sort of thing Mr. Montague would say. That’s why I thought you two might get along.”

“Montague? Not Alden Montague, the writer? This is his house?” Jess looked at me questioningly to see if I’d known it was the old Montague place, but Katrine, ignoring—or perhaps not noticing—Jess’s appalled tone, saved me.

“I thought you might know him, Jess being a writer and since you both went to Bailey. He’s looking for a caretaker for the estate. A couple, preferably. He’s not paying much, but it’s free rent and I’d think it would be a wonderful place to write. It could be just the thing for your . . . circumstances.”

I glanced at Katrine, reassessing her. Beneath the highlighted blond hair and fake English country getup and plastered-on Realtor’s smile she was smart, smart enough to see through our dithering over the aluminum siding and cracked linoleum to realize we couldn’t afford even the cheapest houses she’d shown us today.

“But you wouldn’t get a commission on that,” I pointed out, half to give Jess a chance to get ahold of himself. The last person who’d mentioned Alden Montague around him had gotten a black eye for his trouble.

“No,” she admitted, “but if someone was on the grounds fixing up the place it would sell for a lot more when the time came—and if that someone planted a bug in Mr. Montague’s ear to use a certain Realtor . . .”

She let her voice trail off with a flip of her blond hair and a sly we’re-all-in-this-together smile that I was sure Jess would roll his eyes at, but instead he smiled back, some of that golden light returning to his face.

“In other words,” he said in the silky drawl he used for interviews, “you don’t give the old man much longer to live and you want an accomplice on the inside.”

To her credit, Katrine didn’t even sham surprise.

“I wouldn’t put it quite like that. But the word around town is that Mr. Montague is a pretty sick man. I have no intention of taking advantage of that, but I did think the situation might be mutually beneficial . . .”

Jess grinned. “Why then, by all means, set up the interview. I’d give good money to see Old Monty on his deathbed.”

THE ARRANGEMENTS WERE made so quickly—Katrine purring into her cell phone by the side of the road while Jess and I stood at the gate—that I suspected the “interview” had been set up beforehand. Katrine must have known we’d be interested, which meant we must have smelled as desperate as we really were.

“You’re not seriously thinking of doing this,” I said to Jess when Katrine excused herself to make another call to change “a few previous engagements.” “After what Monty did—”

Jess winced. He hated any reference to “the review” but then he turned that look of pain on me and I knew that wasn’t what he was thinking about. “I thought you’d want to see him. He always liked your stories.”

Now it was my turn to wince. It was true that Alden Montague—or Old Monty as he had been called around the college by both his friends and enemies—had said a few nice things about my stories, but I had come to suspect that he had singled me out because my sophomoric attempts hadn’t threatened him as much as Jess’s writing had. A point borne out when Alden Montague wrote a damning review of Jess’s first book.

“He felt sorry for me,” I told Jess, not for the first time. “The local girl surrounded by all you big city sharks. I’m sorry to hear he’s sick, though. It’s kind of sad to think of him all alone up there in that moldering pile.”

“Are you kidding?” Jess snorted. “He’s become a character in one of those dreadful Gothic novels he so admires. I just want to see him. Maybe he’ll be in a wheelchair with a moth-eaten afghan over his lap . . . Ooh! Maybe he’s on an oxygen machine.”

I swatted his arm. “That’s awful, Jess.” There wasn’t much conviction in my voice, though. The review had been damning and, coming from his former teacher, had crippled Jess’s attempts to write for years. Not bad, but not all that good either, was one phrase I often heard Jess repeating in a perfect imitation of Alden Montague’s patrician drawl.

This past winter, though, just when things had seemed the worst and after two aborted drafts that he’d literally burned, Jess had started working in earnest, and I didn’t want a reminder of Alden Montague to derail him. I was going to suggest that we simply leave—we could look elsewhere for a less expensive house, further west in the Catskills, perhaps—but just then Katrine came toward us.

“He says the keys to the gate are in the third mailbox to the right.” She pointed to a row of warped and listing metal mailboxes to the right of the gate pillar.

“Why so many mailboxes?” I asked, as I struggled to open the rusted metal flap.

“Over the years Mr. Montague has rented out some of the outbuildings, to Bailey students, a new-agey type who makes puppets for the Halloween parade and tells fortunes, a metal artist who works in the south barn—”

The flap came suddenly loose and something long and black slithered out of the mailbox. I screamed and jumped back as the snake fell inches from my foot. It wound itself into a figure eight and drew back its wedge-shaped head. Before it could strike, Jess brought down the heel of his heavy boot onto its head.

I screamed again, more from surprise at Jess’s violent and swift response. When he lifted his boot I could see that the snake’s head had been crushed.

“Quick thinking,” Katrine said, peering over my shoulder, apparently unruffled by the appearance of the snake or Jess’s action—which still had my heart racing. “It’s a rattler.”

“Was a rattler,” Jess said, kneeling to examine his kill.

“I’d forgotten there were snakes up here,” I said, thinking that here was another reason to turn around and head back to the city. “We got them at our farmhouse—”

“The old Jackson place, right?” Katrine asked. “I thought I recognized you.”

I smiled, trying to recall her face, but drawing a blank. “I’m sorry . . .”

“Oh, you wouldn’t remember me. I was a year behind you and not in honors classes like you were. I went to Dutchess Community for two years and then SUNY Potsdam. By the time I got back you had already graduated from Bailey and gone to live in the city. Married to that famous writer”—she turned toward Jess and smiled—“and valiant snake killer. Do you think you could get those keys now?”

Jess looked skeptically at the mailbox but under Katrine’s bright smile—the same bright smile she’d used when assuring us that the watermarks in the last basement we’d seen had come from a broken boiler and not habitual flooding—gamely stuck his hand in to retrieve the keys. As he pulled his hand out he jarred a vine hanging over the gate pillar, uncovering a marble plaque with the words “River House” carved on it—only the last letter had been defaced. It looked as if someone had taken a chisel to it and crudely carved in an “n.” I peered closer and heard Jess, reading over my shoulder, bark a dry laugh as he read the reconfigured name.

“Oh,” Katrine said, looking more uncomfortable about this than the venomous snake. “Some vandal’s idea of a joke—unfortunately one that’s stuck. People in the village call it that because of . . . well, you’ve probably heard the stories, Clare.” With that she passed through the gate.

Jess was still staring at the plaque. “Riven House,” he said aloud. It might as well be called Broken House.” Then he grinned. “Perfect place for a broken-down writer, eh?”

NOW THAT KATRINE had mentioned it, I did remember hearing some locals call the old Montague place “Riven House” because of its unhappy history, but I’d also heard people call it the widow’s house. Sometime back in the thirties the owner of the house had been killed in a shooting accident. His grieving widow was said to have wandered the house and grounds, crying inconsolably and finally killing herself. Even then, the townspeople said, she was seen walking the grounds or appearing at windows, a specter of grief and remorse. The house had slid into decay after that, but that wasn’t uncommon for these old Hudson River mansions, which often enough had their stories of scandal, financial ruin, madness, ghosts, and declining maintenance. As we got closer to the house it became even more apparent what truly bad condition it was in. Chunks of the sandstone trim had fallen clean off the brick façade. The bricks were pitted and pockmarked, as if the house had at one time had a case of smallpox. A swath of ivy hung over half the façade like a veil the house had donned to hide its marred face. A widow’s veil, I found myself thinking. The whole house looked as if it had gone into mourning.

As we walked up the hill we passed an old apple orchard that looked like it was suffering from fire blight. I had the feeling that all the surrounding vegetation was creeping toward the house. Even one of the apple trees had broken free from the ranks of the orchard and was listing against the side of a clapboard addition built onto the north side of the house. We were walking through knee-high grass—remembering the snake, Katrine’s boots no longer seemed like an affectation—which surrounded the house like a green whispering sea. The front door hung marooned over a flight of demolished stairs, giving the house the look of a stranded ship wrecked on a coral reef. I wouldn’t have been surprised to see crabs crawling out of its blind eye-socket windows; I did notice swallows darting in and out of the attic windows.

“It looks like a medieval tower,” Jess remarked.

“It’s an octagonal house,” Katrine replied. “They were quite a fad in the mid-nineteenth century. People believed they generated some kind of vital energy.” Katrine laughed to show she didn’t hold with such new-age nonsense but would happily use it to sell a house. “This is one of the most famous examples. You can see the glass skylight in the central dome . . .”