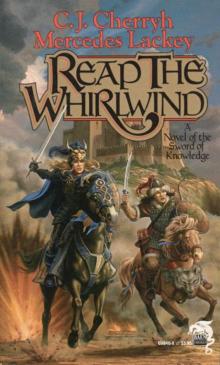

Reap the Whirlwind

C. J. Cherryh

REAP THE

WHILWIND

Book iIi of

The Sword of Knowledge

C. J. Cherryh & Mercedes Lackey

Contents

Dedication:

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

Dedication:

To my partners in crime:

Nancy Asire, Leslie Fish

But most of all, to the lady who made it all possible for all three of us

C. J. Cherryh

with respect, admiration, and a touch of impertinence

CHAPTER ONE

Felaras stood in the open window of her study and let the cold night wind whirl around her, tying her hair into knots and cutting through the thick red wool of her tunic. That wind was the herald of a storm crawling its way toward her; thunderheads blackening the already dark night sky, growling and rumbling. Lightning danced along the tops of the mountains to the east in blue-white arabesques; jagged streaks of fire that leapt from the clouds to lash the world's bones.

There was no real need for Felaras to endure the ice-fanged wind. The study traditionally belonging to the Head of the Order of the Sword of Knowledge had one of the few glazed windows in the Fortress. Felaras could have shut that window and still been able to see the storm. But the current Master of the Order preferred to feel the wild wind on her face this night. The wind was uncontrolled and cleansing, and she had a need to remind herself that such forces existed beyond the petty squabblings of humans. That they would continue no matter what happened here below. That they waited for some human to learn their whys and wherefores, and to tame them to human hands. And one day—one day she knew it would happen. Some day, some man or woman would call the lightning, and it would answer.

For a moment it almost seemed to Felaras that if she called in her need, it would answer her.

But—no.

Hubris, old woman. Hubris and desperation. The gods aren't listening—if they ever did.

The storm wouldn't answer her, as the superstitious believed—but it was nice to imagine, for a few moments, that the foolish tales about the "Order of Sorcerers" were truth.

Ah, you winds—if only you would blow those damned horse-nomads right off the face of the earth—or at least back to their steppes.

She sighed, and lifted her face to the first scent of cold spring rain.

Gods above and below, I do not need this mess. An invading horde—and me expected to magic up an army. I don't suppose they'll take this storm as a sign from their gods to turn around and go home—

Someone pounded on the outer gate, set into the Fortress wall almost directly below her window.

I'm the only one going to hear you, sirrah. You'd best find the right way of getting our attention before you break your fist. Unless you really didn't intend to spoil the wizards' rest, just make a show of trying.

But after doubtless bruising his knuckles on the obdurate portal without getting a response, the pounder discovered the bell rope and set up a brazen clangor not even the thunder could drown.

That one of the valley-folk would dare the storm and the wizards' wrath could only mean one thing.

—my luck's out.

Felaras remained at the window savoring her last few moments of freedom, while Watcher novices scuttled about with torches and lanterns, and the gate below creaked open and shut again. Her hair might be mostly grey, and she might be moving a bit stiffly on winter mornings, but there was nothing wrong with her ears—she heard every stumble the messenger made on the stone staircase leading to her study, and heard how long it took him to recover and resume the climb.

Whoever he is, and judging by the weight and pacing it's either "he" or a damned big woman, he's fagged out. Must've come all the way from the other end of the Vale on his own two feet.

A light tap on her door; then the creak of the door itself. The wind streamed in as the newly opened door created a draft, plastering Felaras's clothing against her chest and legs.

"Master, a messenger from the Vale." Felaras knew that voice; a high, breathy soprano, female, and more often heard shaped into profanity than into such a studiously respectful phrase. That was Kasha, Felaras's own Second and strong right hand, and she was putting on the full show for the newcomer.

"Bring him in," Felaras replied, only now surrendering her last fragments of pretended peace; closing the window and turning to face the room.

It took a moment for her eyes to adjust to the lamplight; a moment while tiny Kasha opened the study door wide and the messenger shuffled uneasily into the soft yellow glow.

Farmer, and, like Kasha, almost pure Sabirn; his race was plain enough, he was smallish and dark, and Felaras read his trade in the tanned, weathered face with the oddly pale forehead where his hat-brim would shade him all through the long cycle of plant, tend, reap. Read it in the stoop of the shoulder and the hard, clever hands; the wrinkles around the eyes that spoke of years watching the sky for the treacherous turning of the weather.

And also read the fear of something worse than the wizard he was facing, for the farmers of the Vale were directly in the path of the oncoming horde.

Not a man that she knew personally. Ah gods, one of the superstitious ones. Which means my people have their hands full. Worse and worse.

He shivered; from nervousness, and from cold. He was soaked to the skin, and as he stood before her, twisting his hat into a shapeless mass, a puddle of rainwater was collecting on the polished wood at his feet.

Poor, frightened man. You may be Sabirn, but you re as legend-haunted as any of the Ancar.

"Kasha—hot wine for the Landsman—"

Kasha nodded, round face as unreadable as a brown pebble, and slipped out the door without making a sound.

High marks for the stone face, m'girl, and high for spook-silence, but a demerit for not thinking of the wine yourself.

Felaras ghosted around her desk and slid into her massive chair with no more noise than Kasha had made. She nodded and waved her hand at the heavy chair beside the farmer.

"Sit, man; a little water isn't going to harm the furnishings."

While he was gingerly seating himself she reached over to the fireplace and gave the inset crank of the hidden bellows a few turns. The flames roared up and the man jumped, and stared at her with eyes that looked to be all startled pupil.

Gods.

"Just a kind of bellows, Landsman. Built right into the -chimney—like what your smith has in his forge."

Felaras cranked it again, sending the flames shooting higher.

"I thought that you needed some quick heat, from the look of you."

The farmer relaxed; a tiny, barely visible loosening of his shoulder muscles and his grip on his hat. "Aye that," he agreed slowly. "Storm in th' Vale; raced it here."

"So I see." She leaned back in her chair, rested her elbows on the carved wooden arms, and steepled her fingers just below her chin. "And raced it because of the barbarians, I presume?"

"Aye. They be just beyond th' Teeth." He leaned forward, hands once again white-knuckled from the grip on what remained of his hat. "Master, they be comin' straight for us—on'y way through's the Vale. We need yer help! We need yer wizard-fire!"

Felaras stifled a groan. "Landsman—excuse me, but what is your name, man?"

He gulped, then offered it, like a gift. "Jahvka."

"Your name is safe with me, Jahvka. I am Felaras, Master only of th

ose who allow me to guide them; I am not your Master, and you need not call me so."

A bit of a lie, though not in spirit—

"Now hear me and believe me, Jahvka; the Order cannot stop these nomads."

He looked shaken and began to object in dismay. "But—the wizard-fire—the magic—"

She shook her head. "The truth, as others would doubtless have told you if they didn't have their hands full, is that we have no more magic than these barbarians. The wizard-fire isn't magic, Jahvka, it's just something like my bellows. We have twelve fire-throwers, of which six are built into the walls and can't be moved. That leaves six more. How many passes into the Vale besides the Teeth?"

His eyes went blank for a moment as he thought. "Dozen, easy. More 'f ye count goat-tracks."

"And those steppes ponies are as surefooted as goats, let me tell you." She leaned forward, gripping the arms of the chair to channel her own anxiety into something that wouldn't show. "We can't cover all the passes with the fire-throwers, and nothing less is going to stop them. They're trapped between us and the River Ardan, and there's no fording that now that the spring rains have started. I have no army, and getting one out of Ancas or Yazkirn is—not bloody likely. I've tried; they won't believe the nomads are a threat until they're trampling the borders. We are—expendable. Have you any suggestions? I am not being sarcastic, Jahvka, if you have any, I'd like to hear them, because I'm fresh out of ideas."

He swallowed, bit his lip, then looked her squarely in the eyes. "Nay. Nothin'. They been eatin' Azgun alive—"

"I know." She sighed, and sagged back into the chair. "All right—here's my only suggestion, Jahvka. You go home, and you tell your people to run; make for the hills. There's caves, you'll be sheltered and safe—" She raised her voice, though not her eyes. "Kasha, get me copies of the maps of the caves—"

Kasha had made another silent entrance; in her charred-grey tunic and breeches she was a lithe, dark-haired shadow. Jahvka started as she set the earthenware mug of hot wine on the desk in front of the farmer, made a tiny bow, then slid back out without speaking.

Now if I could only get her to give me that kind of respect when there aren't strangers about. . . .

"We'll give you complete maps of the caves; we've been stowing what we could in there against some time of need like this one for as long as we've been here. You people can take your choice; you can head either for there or come here to Fortress Pass and go through. We can hold this place against all comers, and it's the only way into Yazkirn for miles about. We'll keep this bunch off your tails if you want to go for sanctuary in Yazkirn or Ancas."

"But—" he gestured helplessly, hat still clutched in one hand. "The plantings—the stock—"

"What won't come willingly, easily, kill and leave behind. Seed can be replaced."

—I hope. Are you listening, gods?

"And stock can be bred back or bought. The land won't run away. The one thing we cannot replace is you, your families, your lives. Listen to me, man. It'll be a hungry winter, but if you take what you can and destroy what you have to, these nomads will have nowhere to go and nothing to raid. Then they'll try the pass—when we scare them off, they'll go home."

—oh you gods, I hope you're hearing me—

"Then you can come back; we'll work together to make your lands bloom again. But we cannot sow a seed that will bring forth your dead; and your wives, your children, and you yourselves will die if you don't run from these horse-warriors while you can!"

She closed her eyes for a moment and pinched the bridge of her nose, feeling a headache coming on.

Jahvka looked about ready to cry; she didn't much blame him. She was about at that point herself.

"Drink your wine," she said gruffly.

He looked at the mug as if he had forgotten it was there, then, as obediently as a child, picked it up and cautiously sipped it, his eyes never once leaving her face.

"It isn't the end of the world, Jahvka," she said quietly. "I know it seems like it is, but its not. The Order ran farther, faster, and with less than you'll be able to save, and we survived."

He bobbed his head, but his eyes were doubtful in the lantern-glow.

"So tell me; what's your people's choice likely to be? Sanctuary or the caves?"

"What you got in them caves?" he asked bluntly. "What they like?"

"Well, let me think; fodder mostly, there's wild grass all over those hills and we set the novices out for a haying holiday every summer."

And fair bitching I used to hear about it, too. No novices to cook and clean and run errands for four whole weeks. Now maybe my lazy children will understand why I ordered it.

"The upper caves are dryer than this Fortress; there's hay up there ten years old that's still good. Some grain; not as much as I'd like, though, and no good for seed. And some things you folk have no use for, books and the like."

Oh precious blood of our Order, you books. Stay safe.

"If I were to put my people up there, I'd put the stock in the upper caves near the fodder and where they can smell the outside; they won't get so twitchy that way. The middle caves would be best for living; the lower are damp at best. There's a couple underground rivers and a lake, so you'll have good water."

Jahvka took all this in, and nodded. "The caves, then; be hard enough gettin' most of 'em out of sight of their land. Most of 'em likely to see goin' over Fortress Pass as givin' up. And my kind don't give up easy."

She inclined her head with real respect. "I take it, then, that you speak for the whole Vale?"

"Aye. I didn't want it, but I was the only Elder still in the Vale, able t' leave the people with someone else, and fit enough to run up here. Mera's on the Teeth with some of the wilder kids; she reckoned on giving them something to do that'd keep 'em out of bowshot. Other younger ones, they with their people, keepin' 'em calm. Old Thahd's with mine; he got wounded he don't want t'leave, so he's watchin' both our garths. Lenyah an' Beris are too damned old t' be runnin' about in a storm."

"No argument from me."

I trained Mera myself; she's no Watcher, but she's as canny as they come. Same for the other younger ones; and I'd bet on them getting their folks ready to march right now. They knew what my answer was going to be. Wounded—I don't like the sound of that; I'll send somebody on down to see if we can do anything. If only these farmers had horses instead of oxen—if only we had more of them trained.

"Will you have enough able-bodied folks in your two garths to run the alert through the Vale?"

He nodded emphatically. "Guess we got no choice, an' might as well go now. Most seed hasn't been put in yet; likely we can save it. 'F Mera an' the lads can hold the Teeth a bit, might even be able t' save the oxen."

Felaras sighed, and glanced out the window. The storm was almost on top of them; she could hear the low grumble of the thunder even through the thick stone walls. A moment later Kasha slipped back in the door, her hands full of waterproofed map-tubes.

"Right enough." She stood up; he nearly overset the chair in his haste to get to his feet. "Kasha, take Elder Landsman Jahvka down to the Lesser Hall and send a novice out for some food for him. Not even a barbarian horse-nomad is going to make a move in this rain, so see him fed and completely dry before you let him go back down the Pass. Tell Vider I want him to go along; the Elder says they've got some wounded. Then get Zorsha to do a supply inventory—yes, I mean now, I want it on my desk before I go to bed—and have Teokane see if the Library has anything to say about these steppes riders."

Kasha bowed—a little more deeply, this time—and ushered the Elder out with one unobtrusive hand behind his left shoulder blade. She closed the door behind them, and Felaras sank back down into her chair just as the first burst of rain pattered against the glass of the window.

Damn. Damn, damn, damn.

She reached for the thin pile of reports. No one would believe her three months ago when she'd figured these nomads wouldn't turn back when they reached the River. H

alf the Order had figured her for crazed, sending out Watchers to try to get information on the barbarians.

Now they'd be on her back to evacuate.

Evacuate to where? The biggest sister-house, the one at Yafir, is right in their path if we fall. The other one at Parda is there on sufferance; in no way are the Yazkirn princes going to let more "wizards" in at their back door.

She skimmed through the hastily written reports one more time, hoping to pry a little more information out of the barely legible scrawls, but didn't learn anything she didn't already know. No ideas as to the size of the "horde"; their habit of having four to six ponies each made them hard to estimate.

Their course was easy enough to follow. They'd cut their way through nominally "civilized" Azgun in a straight run west with Fortress Pass right on the line through Yazkirn; didn't stop for much of anything and seemed to loot only the most portable of goods, mainly the foodstuffs and the horses.

Hm. Wonder why? Usual style is to pillage everything that isn't nailed to the floor, and round up the herds and the kids and women.

She made a mental note to herself to consider that question later, and went on with her gleaning. She chewed absently at her ragged thumbnail as lightning flashed by right outside the window and the stone walls vibrated to the thunder.

The leader was very young, by all accounts; a nomad going by the name of Jegrai. The group was not just a raiding party; their women and children were with them. But not their food herds. Or their family tents and carts. Only their horses. Their riding horses, their packhorses.

Another anomaly. Strange. Very strange.

She came to the end of the reports with nothing more than questions, no answers.

She leaned her head back against the leather of the chair cushion, closed her eyes, and tried to take the whole mess she was facing down to its component parts. If all things were wonderful and I wasn't having to fight my own people, what would our options be?