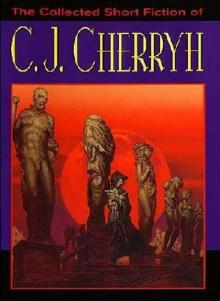

The Collected Short Fiction of C J Cherryh

C. J. Cherryh

THE COLLECTED SHORT FICTION OF C.J. CHERRYH

Table of Contents

Introduction

SUNFALL

Introduction

Prologue

The Only Death in the City (Paris)

The Haunted Tower (London)

Ice (Moscow)

Nightgame (Rome)

Highliner (New York)

The General (Peking)

Introduction to MasKs

MasKs (Venice)

VISIBLE LIGHT

New Introduction

Original Introduction

Frontpiece

Cassandra

Threads of Time

Companions

A Thief in Korianth

The Last Tower

The Brothers

Endpiece

OTHER STORIES

The Dark King

Homecoming

The Dreamstone

Sea Change

Willow

Of Law and Magic

The Unshadowed Land

Pots

The Scapegoat

A Gift of Prophecy

Wings

A Much Briefer History of Time

Gwydion and the Dragon

Mech

The Sandman, the Tinman, and the BettyB

INTRODUCTION

I started writing when I was ten, when I hadn't read any short stories—or if I had, I didn't think of them as short stories. Stories are as long as stories need to be, and no longer, and I'd never read one that wasn't, from Poe to Pyle. So it never occurred to me that there were classes and classifications of stories. I read stories that appealed to me. I wrote stories until I satisfied the story. Mostly my stories, the ones I wrote, worked out to about two hundred pages handwritten. When I learned to type (self-taught) the stories (also self-taught) blossomed to five hundred pages single-spaced.

The typing picked up to a high speed. The stories, fortunately, did not proportionately increase in length. I sold professionally—my first novel went to DAW Books, which has graciously proposed this collection of short stories.

But at the time I was writing that first novel, common wisdom said that the route to professional writing lay through short stories and the magazines.

I just didn't think of stories that short. Novels it was. Novels it stayed—until I had several on the stands.

Then I began to say to myself that I could write short stories, if I figured out how they worked.

Now, be it understood, a short story is really not a novel that takes place in three to five thousand words. It's a very different sort of creature, compressed in time and space (usually), and limited in characterization (almost inevitably).

Since characters and near archaeological scope are a really driving element of my story-telling, I began to see why I'd never quite written short.

But when I began thinking of the problem in that light, I began to see that the tales I'd used to tell aloud on certain occasions, whether around the campfire or in the classroom, tolerably well fit the description. So I wrote one out: the Sisyphos legend. And a modern take on Cassandra. The latter won the Hugo Award for Best Short Story, surprising its creator no end, and I have since written short stories mostly on request, and when some concept occurs to me which just doesn't find itself a whole novel.

It's rare that I'm not working on a novel. Short stories often happen between novels. Consequently my output is fairly small. But I love the tale-telling concept, the notion that I can spin a yarn, rather than construct something architectural and precise. So I think most of my short stories are more organic than not. I became aware, when I thought closely about it, that that Poe fellow I liked was a short story writer—in fact, I'd learned he was the father of the short story—but I'd just never analyzed what he did; and to me it still seems more like tales than architectural structure. You fall into them. Same with Fritz Leiber's wonderful Mouser stories. I never counted the words in them. I just lapped them up for what they were—and then analyzed just how he did it, because it seemed to me, and still seems, that he was one of the most natural, seamless tale-tellers of the last two centuries. I like that kind of story I hope I can do a few.

I enjoy the chance to do them. I write the kind I like to read. Or the kind the idea of which starts to nag me, so I have to write it, or it begins to occupy my subconscious to such an extent I get nothing else done.

But most are because someone asks me to. The first question writers ever get asked by the general public is "Where do you get your ideas?" Just imagine, if someone said, "Write a story about—an island. People stranded on an island." Well, that would work. Being a science fiction writer, I can think of various definitions of "island" and various definitions of "people," from ship in trouble to stuck elevator to real tract of sand. Then you tell me that it has to be short—and I have to say, well, we can't go too deeply into the people, but we can have a situation. We can have a compression of time and a really dire necessity That's a source of ideas. If I were set down on an island in a crisis, I can assure you I'd have ideas. . . as I think my readers would have, themselves. So Ideas aren't the be-all and end-all. The question that drives the short story is—what's unique about your situation? What's the question, what's the problem? And how are you going to fix it?

It's not the only way to do it, but it's one way to do it. It's not a formula, it's a set of questions. And I hope if anything a few of my tales leave you thinking of your own solutions.

Thanks to Betsy Wollheim, my extremely patient and dedicated publisher, who thought of doing this volume, and who kept after the project until it all worked. You have the result of her persistence in your hands.

—CJ Cherryh, Spokane, 2003

SUNFALL

I've always thought well of cities. They're ecological (think of all those millions turned loose with axes to burn firewood in the forest, each with an acre or two, and contemplate the footprint they'd leave in, say, the Adirondacks or the Rockies.) And they're a library of our culture and our past (consider Rome, Osaka, Los Angeles, and Chattanooga, as history and cuisine and human psychology.) Might all cities be haunted—repositories of the restless spirits of all the lives that have ever passed there? Might they shape their modern inhabitants subtly and constantly, as new individuals tread old, old paths and cross old, old bridges for the same reasons as thousands of years ago?

Sunfall is the wonder and the power of cities. I take it as one of the highest compliments that Fritz Lieber, whose writing I greatly admired, loved it, and troubled to tell me so—he was a kindred soul on this point. Myself, I love the woods. I love the wild places. Ask me where I'd go for a vacation and it invariably involves the open country. Ask me where I'd live, however, and it would always be in the center, in the beating heart of a city. And I'm very happy with these stories. I'm delighted to see them in another edition.

CJC

1981

PROLOGUE

On the whole land surface of the Earth and on much of the seas, humankind had lived and died. In the world's youth the species had drawn together in the basins of its great rivers, the Nile, the Euphrates, the Indus; had come together in valleys to till the land; hunted the rich forests and teeming plains; herded; fished; wandered and built. In the river lands, villages grew from families; irrigated; grew; joined. Systems grew up for efficiency; and systems wanted written records; villages became towns; and towns swallowed villages and became cities.

Cities swallowed cities and became nations; nations combined into empires; conquerors were followed by law-givers who regulated the growth into new systems; systems functioned until grandsons proved less able to rule

and the systems failed: again to chaos and the rise of new conquerors; endless pattern. There was no place where foot had not trod; or armies fought; and lovers sighed; and human dust settled, all unnoticed.

It was simply old, this world; had scattered its seed like a flower yielding to the winds. They had gone to the stars and gained. . . new worlds. Those who visited Earth in its great age had their own reasons. . . but those born here remained for that most ancient of reasons: it was home.

There were the cities, microcosms of human polity, great entities with much the character of individuals, which bound their residents by habit and by love and by the invisible threads that bound the first of the species to stay together, because outside the warmth of the firelit circle there was dark, and the unknown watched with wolfen eyes.

In all of human experience there was no word which encompassed this urge in all its aspects: it might have been love, but it was too often hate; it might have been community, but there was too little commonality; it might have been unity but there was much of diversity. It was in one sense remarkable that mankind had never found a word apt for it, and in another sense not remarkable at all. There had always been such things too vast and too human to name: like the reason of love and the logic in climbing mountains.

It was home, that was all. . .

And the cities were the last flourishing of this tendency, as they had been its beginning.

1981

THE ONLY DEATH IN THE CITY

(Paris)

It was named the City of Lights. It had known other names in the long history of Earth, in the years before the sun turned wan and plague-ridden, before the moon hung vast and lurid in the sky, before the ships from the stars grew few and the reasons for ambition grew fewer still. It stretched as far as the eye could see. . . if one saw it from the outside, as the inhabitants never did. It was so vast that a river flowed through it, named the Sin, which in the unthinkable past had flowed through a forest of primeval beauty, and then through a countless succession of cities, through ancient ages of empires. The City grew about the Sin, and enveloped it, so that, stone-channelled, it flowed now through the halls of the City, thundering from the tenth to the fourteenth level in a free fall, and flowing meekly along the channel within the fourteenth, a grand canal which supplied the City and made it self-sufficient. The Sin came from the outside, but it was so changed and channelled that no one remembered that this was so. No one remembered the outside. No one cared. The City was sealed, and had been so for thousands of years.

There were windows, but they were on the uppermost levels, and they were tightly shuttered. The inhabitants feared the sun, for popular rumor held that the sun was a source of vile radiations, unhealthful, a source of plagues. There were windows, but no doors, for no one would choose to leave. No one ever had, from the day the outer walls were built. When the City must build in this age, it built downward, digging a twentieth and twenty-first level for the burial of the dead. . . for the dead of the City were transients, in stone coffins, which might always be shifted lower still when the living needed room.

Once, it had been a major pastime of the City, to tour the lower levels, to seek out the painted sarcophagi of ancestors, to seek the resemblances of living face to dead so common in this long self-contained city. But now those levels were full of dust, and few were interested in going there save for funerals.

Once, it had been a delight to the inhabitants of the City to search the vast libraries and halls of art for histories, for the City lived much in the past, and reveled in old glories. . . but now the libraries went unused save for the very lightest of fictions, and those were very abstract and full of drug-dream fancies.

More and more. . . the inhabitants remembered.

There were a few at first who were troubled with recollections and a thorough familiarity with the halls—when once it was not uncommon to spend one's time touring the vast expanse of the City, seeing new sights. These visionaries sank into ennui. . . or into fear, when the recollections grew quite vivid.

There was no need to go to the lower levels seeking ancestors. They lived. . . incarnate in the sealed halls of the City, in the persons of their descendants, souls so long immured within the megalopolis that they began to wake to former pasts, for dying, they were reborn, and remembered, eventually. So keenly did they recall that now mere infants did not cry, but lay patiently dreaming in their cradles, or, waking, stared out from haunted eyes, gazing into mothers' eyes with millennia of accumulated lives, aware, and waiting on adulthood, for body to overtake memory.

Children played. . . various games, wrought of former lives.

The people lived in a curious mixture of caution and recklessness: caution, for they surrounded themselves with the present, knowing the danger of entanglements; recklessness, for past ceased to fascinate them as an unknown and nothing had permanent meaning. There was only pleasure, and the future, which held the certainty of more lives, which would remember the ones they presently lived. For a very long time, death was absent from the halls of the City of Lights.

Until one was born to them.

Only rarely there were those born new, new souls which had not made previous journeys within the City, babes which cried, children who grew up conscious of their affliction, true children among the reborn.

Such was Alain.

He was born in one of the greatest of families—those families of associations dictated more by previous lives than by blood, for while it was true that reincarnation tended to follow lines of descendancy, this was not always the case; and sometimes there were those from outside the bloodline who drifted in as children, some even in their first unsteady steps, seeking old loves, old connections. But Alain was new. He was born to the Jade Palace Family, which occupied the tenth level nearest the stairs, although he was not of that family or indeed of any family, and therefore grew up less civilized.

He tried. He was horribly conscious of his lack of taste, his lack of discrimination which he could not excuse as originality: originality was for—older—minds and memories. His behavior was simply awkward, and he stayed much in the shadows in Jade Palace, enduring this life and thinking that his next would surely be better.

But Jade was neighbor to Onyx Palace, and it was inevitable that these two houses mix upon occasion of anniversaries. These times were Alain's torment when he was a child, when his naive and real childhood was exposed to outsiders; they became torment of a different kind in his fourteenth year, when suddenly his newly maturing discrimination settled upon a certain face, a certain pale loveliness in the Onyx House.

"Only to be expected," his mother sighed. He had embarrassed her many times, and diffidently came to her now with this confession. . . that he had seen in this Onyx princess what others saw within their own houses; an acuteness of longing possessed him which others claimed only for old recognitions and old lovers of former lives. He was new, and it was for the first time. "Her name," his mother asked.

"Ermine," he whispered, his eyes downcast upon the patterns of the carpets, which his aunt had loomed herself in a long-past life. "Her name is Ermine."

"Boy," his mother said, "you are a droplet in the canal of her lives. Forget her."

It was genuine pity he heard in his mother's voice, and this was very rare. You entertain me, was the kindest thing she had yet said to him, high compliment, implying he might yet attain to novelty. Now her kind advice brought tears to his eyes, but he shook his head, looked up into her eyes, which he did seldom: they were very old and very wise and he sensed them forever comparing him to memories ages past. "Does anyone," he asked, "ever forget?"

"Boy, I give you good advice. Of course I can't stop you. You'll be born a thousand times and so will she, and you'll never make up for your youth. But such longings come out again if they're not checked, in this life or the next, and they make misery. Sleep with many; make good friends, who may be born in your next life; no knowing whether you'll be man or woman or if they'll be what the

y are. Make many friends, that's my advice to you, so that whether some are born ahead of you and some behind, whether sexes are what they are. . . there'll be some who'll be glad to see you among them. That's how one makes a place for one's self. I did it ages ago before I began to remember my lives. But I've every confidence you'll remember yours at once; that's the way things are, now. And when you've a chance to choose intelligently as you do in these days, why, lad, be very glad for good advice. Don't set your affections strongly in your very first life. Make no enemies either. Think of your uncle Legran and Pertito, who kill each other in every life they live, whatever they are. Never set strong patterns. Be wise. A pattern set so early could make all your lives tragedy."

"I love her," he said with all the hopeless fervor of his fourteen unprefaced years.

"Oh my dear," his mother said, and sadly shook her head. She was about to tell him one of her lives, he knew, and he looked again at the carpet, doomed to endure it.

He did not see Onyx Ermine again that year, not the next nor the two succeeding: his mother maneuvered the matter very delicately and he was thwarted. But in his eighteenth year the quarrel Pertito had with uncle Legran broke into feud, and his mother died, stabbed in the midst of the argument.

Complications, she had warned him. He stood looking at her coffin the day of the funeral and fretted bitterly for the loss of her who had been his best and friendliest advisor, fretted also for her sake, that she had been woven into a pattern she had warned him to avoid. Pertito and Legran were both there, looking hate at one another. "You've involved Claudette," Pertito had shouted at Legran while she lay dying on the carpet between them; and the feud was more bitter between the two than it had ever been, for they had both loved Claudette, his mother. It would not be long, he thought with the limits of his experience in such matters, before Pertito and Legran would follow her. He was wise and did not hate them, wrenched himself away from the small gathering of family and wider collection of curious outside Jade Palace, for he had other things to do with his lives, and he thought that his mother would much applaud his good sense.