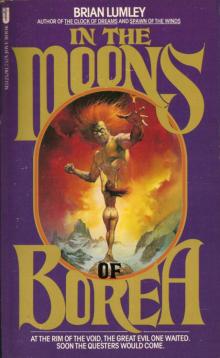

In the Moons of Borea

Brian Lumley

IN THE MOONS OF BOREA

For the 'Old Folks' at No. 25

PART ONE : BOREA

1 Paths of Fate

They skirted the forest on foot, the Titan bears shambling along behind on all fours, their packs piled high so that there was no room for the men to ride. Only three of the animals went unburdened, and these were hardly bears for riding. A stranger party could scarce be imagined. Here were bronze Indians straight out of Earth's Old West, squat, powerful Eskimos from the Motherworld's perpetually frozen north, great white bears half as big again as those of the Arctic Circle, and a tall, ruggedly handsome, leather-clad white man whose open, short-sleeved jacket showed a broad, deep chest and arms that forewarned of massive strength.

To the oddly polyglot party that followed Hank Silberhutte, their Warlord seemed utterly enigmatic. He was a strange, strange man: the toast of the entire plateau and master of all its might, mate to Armandra the Priestess. and father of her man-child, destroyer of Ithaqua's armies and crippler — however briefly — of Ithaqua himself. And yet he mingled with his minions like a common man and led them out upon peaceful pursuits as surely as he led them in battle. Yes, a strange man indeed, and Ithaqua must surely rue the day he brought him to Borea.

Silberhutte the Texan had been Warlord for three years now, since the time he deposed Northan in a savage fight to win Armandra. He had won her, and with her the total command of the plateau's army. That had been before the War of the Winds, when the plateau's might had prevailed over the bludgeoning assault of Ithaqua's tribes, when Ithaqua himself had been sorely wounded by this man from the Motherworld.

Mighty wrestler, fighter who could knock even a strong man senseless with a blow of his huge fist, weapons' master whose skill had quickly surpassed that of his instructors, telepath (though the plateau's simpler folk could not truly understand the concept) who could throw — had thrown — mental insults at Ithaqua, the Wind-Walker, and yet walk away unscathed: Silberhutte was all of these things. He was as gentle as his strength and size would allow; he instinctively understood the needs of his people; when lesser men approached him in awe, he greeted them as friends, equals; he respected the Elders and was guided by their counselling, and his fairness was already as much a legend as his great strength.

When he could by right have slain Northan, his hated, bullying Warlord predecessor — when nine-tenths of the plateau's peoples had wanted Northan dead — Hank Silberhutte had let him live, had given him his life. Later, when Northan turned traitor, siding with Ithaqua and his ice-priests to help them wage war against the plateau, Kota'na the Keeper of the Bears had taken that life, had taken Northan's head too; and even though he was wounded in the fighting, Kota'na would not give up his grisly trophy to any man but his Lord Silberhutte.

And it was Kota'na who came now at an easy lope through the long grass toward where Silberhutte stood, Kota'na, whose proud Indian head was lifted high, eyes alert as those of any creature of the wild. He had scouted out the ground ahead, as two other braves even now scouted it to the rear; for though they were well clear of the territories of the Wind-Walker's tribes, still they were wary of skulking war parties. The Children of the Winds did not usually wander far afield when Ithaqua left them to go striding among the star-voids, but one could never be sure. That was why three of the bears were not in harness; they were fighters, white monsters whose loyalty to their masters was matched only by their ferocity when confronted with their enemies. Now they were nervous, and Hank Silberhutte had noted their anxious snufflings and growlings.

He noted too Kota'na's uneasiness as the handsome brave approached him. The Indian kept glancing toward the dark green shadows of the forest, his eyes narrowing as they sought to penetrate the darker patches of shade. Borea had no 'night' as such, only a permanent half-light, whereby shaded places were invariably very gloomy.

`What's bothering you, bear-brother?' Hank asked, his keen eyes searching the other's face.

`The same thing that bothers the bears, Lord Sil-ber-hutte,' the Indian answered. 'Perhaps it is just that Ithaqua's time draws nearer, when he returns to Borea . . .,' he shrugged. 'Or perhaps something else. There is a stillness in the air, a hush over the forest.'

`Huh!' the Texan grunted, half in agreement. 'Well, here we camp, danger or none. The forest goes on for twenty miles or more yet, Kota'na, so if we're being shadowed, we won't lose our tail until we're beyond the woods. We'll keep five men awake at all times; that should be sufficient. Six hours' sleep, a meal, and then we press on as fast as we can go. Fifty miles beyond the forest belt we'll be back in the snows, and we'll find our sleighs where we left them. The going will be faster then. Fifty miles beyond that, across the hills, we'll sight the moons of Borea where they hang over the rim. Then — '

`Then, Lord, we will be almost within sight of the plateau!'

`Where a pretty squaw called Oontawa waits for her brave, eh?' the white giant laughed.

`Aye, Lord,' Kota'na soberly answered, 'and where the Woman of the Winds will doubtless loose great lightnings to greet the father of her child. Ah, but I am ready for the soft comforts of my lodge. If we were fighting, that would be one thing — but this dreary wandering . .' He paused and frowned, then: 'Lord, there is a question I would ask.'

`Ask away, bear-brother.'

Why do we leave the plateau to wander in the woods? Surely it is not simply to seek out strange spices, skins, and tusks? There are skins enough in the white wastes and more than enough food in and about the plateau.'

`Just give me a moment, friend, and well talk,' Silberhutte told him. He spoke briefly to the men about him, giving instructions, issuing orders. Then, while rough tents were quickly erected and a list for watch duties drawn up, he took Kota'na to one side.

`You're right, bear-brother, I don't come out under the skies of Borea just to hunt for pale wild honey and the ivory of mammoths. Listen and I'll tell you:

`In the Motherworld I was a free man and went wherever I wanted to go, whenever I wanted to go there. There are great roads in the Motherworld and greater cities, man-made plateaus that make Borea's plateau look like a pebble. Now listen: you've seen Armandra fly — the way she walks on the wind — a true child of - her father? Well, in the Motherworld all men can fly. They soar through the skies inside huge mechanical birds, like that machine that lies broken on the white waste between the plateau and Ithaqua's totem temple. He snatched us out of the sky in that machine and brought us here . .

He paused, beginning to doubt Kota'na's perception. `Do you understand what I'm trying to say?'

`I think so, Lord,' the Indian gravely answered. 'The Motherworld sounds a fine and wonderful place but Borea is not the Motherworld.'

`No, my friend, that's true but it could be like the Motherworld one day. I'm willing to bet that hundreds of miles to the south there are warm seas and beautiful islands, maybe even a sun that we never see up here in the north. Yes, and I can't help wondering if Ithaqua is confined to this world's northernmost regions just as he is during his brief Earthly incursions. It's an interesting thought .. .

'As to why I come out here, exploring the woods and the lands to the south: surely you must have seen me making lines on the fine skins I carry? They are maps, bear-brother, maps of all the places we visit. The lakes and forests and hills — all of them that we've seen are shown on my maps. One day I want to be able to go abroad in Borea just as I used to on Earth.'

He slammed fist into palm, lending his words emphasis, then grinned and slapped the other's shoulder. 'But come now, we've been on the move for well over ten hours. I, for one, am tired. Let's get some sleep, and then we'll be on our way again.' He glanced at the grey sky to the north and his face quickly formed a frown. '

The last thing I want is to be caught out in the open when Ithaqua comes walking down the winds to Borea again. No, for he surely has a score to settle with the People of the Plateau — especially with me!'

In no great hurry to find Elysia (Titus Crow had warned him that the going would not be easy, that no royal road existed into the place of the Elder Gods), Henri de Marigny allowed the time-clock to wander at will through the mighty spaces between the stars. In the case of the time-clock, however, 'wander' did not mean to progress slowly and aimlessly from place to place, far from it. For de Marigny's incredible machine was linked to all times and places, and its velocity — if 'velocity' could ever adequately describe the motion of the clock --- was such that it simply defied all of the recognized laws of Earthly science as it cruised down the lightyears.

And already de Marigny had faced dangers which only the master of such a weird vessel might ever be expected to face: dangers such as the immemorially evil Hounds of Tindalos!

Twice he had piloted the time-clock through time itself; once as an experiment in the handling of the clock, the second time out of sheer curiosity. On the first occasion, as he left the solar system behind, he had paused to reverse the clock's temporal progression to a degree sufficient to freeze the planets in their eternal swing around the sun, until the worlds of Sol had stood still in the night of space and the sun's flaring, searing breath had appeared as a still photograph in his vessel's scanners. The second time had been different.

Finding a vast cinder in space orbiting a dying orange sun, de Marigny had felt the urge to trace its history, had journeyed into the burned-out planet's past to its beginnings. He had watched it blossom from a young world with a bright atmosphere and dazzling oceans into a mature planet where races not unlike Man had grown up and built magnificent if alien cities ... and he had watched its decline, too. De Marigny had recognized the pattern well enough: the early wars, each greater (or more devastating) than the last, building to the final confrontation. And the science of these beings was much like the science of Man.

They had vehicles on the land, in the air, and on the water, and they had weapons as awesome as any ever devised on Earth.

. . . Weapons which they used!

Sickened to find that another Manlike race had discovered the means of self-destruction - and that in this instance they had used it to burn their world to a useless crisp - de Marigny would have returned at once to his own time and picked up his amazing voyage once more. But that was when he was called upon to face his first real threat since leaving Earth's dreamworld, and in so doing, he went astray from the known universe.

It was strange, really, and oddly paradoxical; for while Titus Crow had warned him about the Hounds of Tindalos, he had also stated that time's corridors were mainly free of their influence. Crow had believed that the Hounds were drawn to travellers in the fourth dimension much like moths to a flame (except that flames kill moths!) and that a man might unconsciously attract them by his presence alone. They would scent the id of a man as sharks might scent his blood, and it would send them into just such a frenzy!

Thus, as de Marigny flew his vessel forward along the timestream, he nervously recalled what Crow had told him of the Hounds - how time was their domain and that they hid in time's darkest 'angles' - and in this way he may well have attracted them. Indeed he found himself subconsciously repeating lines remembered from the old days as he had seen them scribbled in a book of Crow's jottings, an acrostic poem written by an eccentric friend of Crow's who had 'dreamed' all manner of weird things in connection with the Cthulhu Cycle Deities, or the 'CCD,' and similarly fabled beings of legendary times and places. It had gone like this:

Time's angles, mages tell, conceal a place

Incredible, beyond the mundane mind:

Night shrouded and outside the seas of space,

Dread Tindalos blows on the ageless wind.

And where the black and corkscrew towers climb,

Lost and athirst the ragged pack abides,

Old as the aeons, trapped in tombs of time,

Sailing the tortuous temporal tides ..

And even as he realized his error and tore his thoughts from their morbid ramblings as mental warning bells clamoured suddenly and jarringly in the back of his mind - de Marigny saw them in the clock's scanners .. . the Hounds of Tindalos!

He saw them, and Crow's own description of the monstrous vampiric creatures came back to him word for word:

'They were like ragged shadows, Henri,- distant tatters that flapped almost aimlessly in the void of time. But as they drew closer, their movements took on more purpose! I saw that they had shape and size and even something approaching solidarity, but that still there was nothing about them even remotely resembling what we know of life. They were Death itself — they were the Tind'losi Hounds — and once recognized, they can never be forgotten!'

He remembered, too, Crow's advice: not to attempt to run from them once they found you, neither that nor even to use the clock's weapon against them. 'Any such attempt would be a waste of time. They can dodge the beam, avoid it, even outdistance it as easily as they outdistance the clock itself. The fourth dimension is their element, and they are the ultimate masters of time travel. Forward in time, backward — no matter your vessel's marvellous manoeuvrability or its incredible acceleration — once the Hounds have you, there is only one way to escape them: by reverting instantly to the three commonplace dimensions of space and matter . .

De Marigny knew now how to do this and would ordinarily have managed the trick easily enough, but with the Tind'losi Hounds fluttering like torn, sentient kites about his hurtling vessel, their batlike voices chittering evilly and their nameless substance already beginning to eat through the clock's exterior shell to where his defenceless id crouched and shuddered . .

And so he made his second mistake — an all-too-human error, a simple miscalculation — which instantly took him out of his own timestream, his own plane of existence, leaving him dizzy and breathless with the shock of it. For he had not regained the three-dimensional universe measured and governed by Earthly laws but had sidestepped into one which lay alongside, a parallel universe of marvels and mysteries. One moment (if such a cliché is acceptable in this case) the Hounds of Tindalos were clustered about the time-clock, and the next -

- They were gone, and where they had been, an undreamed-of vista opened to de Marigny's astounded eyes! This was in no way the void of interstellar space as he had come to know it, no. Instead he found himself racing through a tenuous, faintly glowing grey-green mist distantly rippled with banners of pearly and golden light that moved like Earth's aurora borealis, sprinkled here and there with, the silver gleam of strange stars and the pastel glow of planets large and small.

And since his own senses were partly linked with those of his hybrid vessel, he also detected the eddies of an ether wind that caught at the clock to blow it ever faster on an oddly winding course between and around these alien spheres. A wind that keened in de Marigny's mind, conjuring visions of ice and snow and great white plains lying frozen fast beneath moons that bloated on a distant horizon. The moons of Borea . .

2 Paths Cross

[NOTE to this ebook: the paper original from which this ebook was derived was owned by a rare and accomplished Adept and Ipsissimus. He had turned down this page in the book, for use in future reference to this part of the book, of special relevance to him regarding the CCD.]

'Lord Sil-ber-hut-te! Hank! Wake up, Lord!' Kota'na's urgency, emphasized by his use of the Warlord's first name, brought Hank Silberhutte to his feet within his central tent. A moment later he stepped out into the open, shaking sleep from his mind, gazing skyward and following Kota'na's pointing finger. All eyes in the camp were turned to the sky, where something moved across the heavens with measured pace to fall down behind the horizon of forest treetops.

The Warlord had almost missed the thing, had witnessed its flight for two or three seconds only; but in that short t

ime his heart, which he believed had almost stopped in the suspense of the moment, had started to beat again, and the short hairs at the back of his neck had lain down flat once more. Borea was no world in which to be out in the open when there were strange dark things at large in the sky!

But no, the aerial phenomenon had not been Ithaqua, not the Wind-Walker. If it were, then without a doubt Silberhutte's party had been doomed. It had certainly been a strange and alien thing, yes, and one that ought surely not to fly in any world. But it had not been the Lord of the Snows.

`A clock Silberhutte gasped. 'A great-grandfather clock! Now what in the — ' And his voice suddenly tapered off as memory brought back to him snatches of a conversation which had taken place (how many years ago?) in the home of a London-based colleague during the Wilmarth Foundation's war on the CCD, the 'Cthulhu Cycle Deities,' in Great Britain. At that time Silberhutte had not long been a member of the foundation, but his singular telepathic talent had long since appraised him of the presence of the CCD.

Titus Crow had been a prime British mover in that phase of the secret confrontation, and at the home of the learned leonine occultist Silberhutte had been shown just such a clock as had recently disappeared over the treetops. A weirdly hieroglyphed, oddly ticking monstrosity whose four hands had moved in sequences utterly removed from horological systems of Earthly origin. By far the most striking thing about that clock had been its shape — like a coffin a foot taller than a tall man — that and the fact that there seemed to be no access to the thing's innards, no way into its working parts. It was then that Titus Crow had told Silberhutte: